ELMORE LEONARD Anthony May

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elmore Leonard, 1925-2013

ELMORE LEONARD, 1925-2013 Elmore Leonard was born October 11, 1925 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Due to his father’s position working for General Motors, Leonard’s family moved numerous times during his childhood, before finally settling in Detroit, MI in 1934. Leonard went on to graduate high school in Detroit in 1943, and joined the Navy, serving in the legendary Seabees military construction unit in the Pacific theater of operations before returning home in 1946. Leonard then attended the University of Detroit, majoring in English and Philosophy. Plans to assist his father in running an auto dealership fell through on his father’s early death, and after graduating, Leonard took a job writing for an ad agency. He married (for the first of three times) in 1949. While working his day job in the advertising world, Leonard wrote constantly, submitting mainly western stories to the pulp and/or mens’ magazines, where he was establishing himself with a strong reputation. His stories also occasionally caught the eye of the entertainment industry and were often optioned for films or television adaptation. In 1961, Leonard attempted to concentrate on writing full-time, with only occasional free- lance ad work. With the western market drying up, Leonard broke into the mainstream suspense field with his first non-western novel, The Big Bounce in 1969. From that point on, his publishing success continued to increase – with both critical and fan response to his works helping his novels to appear on bestseller lists. His 1983 novel La Brava won the Edgar Award for best mystery novel of the year. -

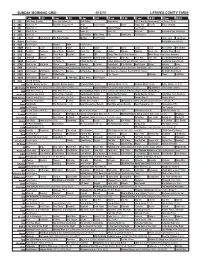

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

Hombre: a Novel

[Read and download] Hombre: A Novel Hombre: A Novel Von Elmore Leonard DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Produktinformation -Verkaufsrang: #277008 in eBooksVerffentlicht am: 2009-10-13Erscheinungsdatum: 2009-10-13File Name: B000FC2IWG | File size: 25.Mb Von Elmore Leonard : Hombre: A Novel before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Hombre: A Novel: KundenrezensionenHilfreichste Kundenrezensionen4 von 4 Kunden fanden die folgende Rezension hilfreich. Leonard's Westerns are the real deal!Von RK HawkinsIt is unbelievable, but true: put your hands on a Leonard western once and you won't be able to get away from them before you've read all there are - once you pop, you can't stop.To my knowledge, there are eight Leonard westerns available at :1. Gunsights2. The Bounty Hunters3. Hombre4. Valdez is Coming5. Last Stand at Saber River6. Escape from Five Shadows7. The Law at Randado8. Forty Lashes Less OneRead them all. That's all I have to say. Read them all and find out just how good they are for yourselves. This is addicting stuff. Cocaine is nothing, compared with a western penned by Elmore Leonard.0 von 0 Kunden fanden die folgende Rezension hilfreich. The script for a great movieVon H. KraussMany of us may have first known it as Martin Ritt's classic Western from 1967 starring Paul Newman. Reading the book you have to try NOT to visualise the scenes in the film. So what can one say, great adaptation!The only major differences are the introductory mustanging scenes in the film and the narrative perspective in the book. -

Jackie Brown (1997)

Jackie Brown (1997) I. Handlung Nach Pulp Fiction stellt Tarantino sich einer besonderen Heraus- forderung und realisiertmit Jackie Brown seine bislang einzige Romanverfilmung. Grundlage für den Film ist RumPunch (1992) vonElmoreLeonard, dessen Hauptfigur den Namen Jackie Burke trägt. Tarantino nennt sie Jackie Brown, eine vonder Schauspiele- rin PamGrier inspirierte Figur,denn diese spielt die Hauptrolle in Jack Hills Blaxploitation-Film Foxy Brown (1974). DieAnspielung ist auch an dem sehr ähnlichen Schrifttyp mit geschwungenen Ober- und Unterlängen zu erkennen, den Tarantino für das Film- plakat gewählt hat. Damit wirdseine Leonard-Adaption zugleich zu einem Grier-Film, allerdings nicht im üblichen Blaxploitation- Stil. Jackie Brown spielt 1995 in Los Angeles und handelt vonder 44-jährigen Stewardess Jacqueline Brown, die beruflich für eine mexikanische Airline und nebenher für den Waffenschmuggler Ordell Robbie als Geldkurier tätig ist. Dieser beauftragt den Kau- tionsagenten MaxCherrydamit, einen seiner Mitarbeiter,Beau- mont Livingston, der gerade ins Gefängnis gekommen ist und somit seinen Auftraggeber möglicherweise verpfeifen könnte, frei- zukaufen, damit er ihn erschießen kann. Da Beaumont aber,bevor er getötet wird, bereits einen Teil sei- nes Wissens preisgegeben hat, wirdJackie am Flughafen wegen Schwarzgeld und Kokain im Gepäck festgenommen. Sieschlägt das Angebot, mit der Polizei zu kooperieren, zunächst aus und muss wegen illegalen Drogenhandels ins Gefängnis. Ordell plant erneut eine Freilassung auf Kaution mit anschließendem Mord. Maxholt Jackie jedoch vomGefängnis ab und warnt sie. Darauf- hin entwendet sie seinen Revolver,mit dessen Hilfe sie Ordell, als er sie töten will, zu einem Handel nötigt: Siewerde der Polizei nur scheinbar helfen, in Wirklichkeit aber eine halbe Million Dollar für Ordell vonMexiko nach Los Angeles schmuggeln. -

Download Pronto a Novel Pdf Book by Elmore Leonard

Download Pronto A Novel pdf book by Elmore Leonard You're readind a review Pronto A Novel ebook. To get able to download Pronto A Novel you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Book Details: Original title: Pronto: A Novel 400 pages Publisher: William Morrow Paperbacks; Reprint edition (January 3, 2012) Language: English ISBN-10: 0062120336 ISBN-13: 978-0062120335 Product Dimensions:5.3 x 0.9 x 8 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 19519 kB Description: “Speedy, exhilarating, and smooth. Nobody does it better.”—Washington Post“The man knows how to grab you—and Pronto is one of the best grabbers in years.”—Entertainment WeeklyFans of U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens of the hit TV series Justified are in for a major treat. The unstoppable manhunter with the very itchy trigger finger stars in Pronto, a crime... Review: Im a fan of the TV show Justified, every week I would see the name Elmore Leonard during the opening credits and I would say to myself I gotta google this guys works! , well when I finally did google Elmore I realized I was familiar with some of his work I just wasnt familiar with Elmore. Turns out he penned a few favorites of mine 3:10 To Yuma,... Ebook File Tags: elmore leonard pdf, raylan givens pdf, jimmy cap pdf, harry arno pdf, riding the rap pdf, timothy olyphant pdf, crime fiction pdf, justified tv series pdf, fire -

Fine Books (1278) Lot

Fine Books (1278) May 31, 2007 EDT, Main Floor Gallery Lot 297 Estimate: $120 - $200 (plus Buyer's Premium) 16 vols. American Hard-Boiled Detective Fiction - Elmore Leonard & James Ellroy - Signed Copies: Leonard, Elmore. City Primeval. New York: Arbor House, (1980). 1st ed. 8vo, orig. bds., d/j. Inscribed & signed by Leonard on 1/2 title. * _ _. Split Images. New York: Arbor House, (1981). 1st ed. 8vo, orig. bds.; edge wear, d/j (residue on flaps). Glue residue & spotting on endpaper. Inscribed & signed by Leonard on title page. * _ _. Stick. New York: Arbor House, (1983). 1st ed. 8vo, orig. bds.; slightly scuffed, d/j (slightly dusty). Inscribed & signed by Leonard on 1/2 title. * _ _. La Brava. New York: Arbor House, (1983). 1st ed. 8vo, orig. bds., d/j. Inscribed & signed by Leonard. * _ _. Glitz. New York: Arbor House, (1985). 1st trade ed. 8vo, orig. bds., d/j. Inscribed & signed by Leonard on 1/2 title. * The 7th ptg of the preceding, orig. bds., d/j, signed by Leonard on 1/2 title. * _ _. Dutch Treat. New York: Arbor House, (1985). 1st trade ed. 8vo, orig. cloth, d/j. Inscribed & signed by Leonard on 1/2 title. * _ _. Double Dutch Treat. New York: Arbor House, (1986). 1st ed. 8vo, orig. bds., d/j. Inscribed & signed by Leonard on 1/2 title. * _ _. Touch. New York: Arbor House, (1987). 1st ed. 8vo, orig. bds., d/j. Signed by Leonard on 1/2 title. * _ _. Bandits. New York: Arbor House, (1987). 1st ed. 8vo, orig. -

![[Idcyr.Ebook] Hombre Pdf Free](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1459/idcyr-ebook-hombre-pdf-free-621459.webp)

[Idcyr.Ebook] Hombre Pdf Free

IdCyR [Download free pdf] Hombre Online [IdCyR.ebook] Hombre Pdf Free Elmore Leonard ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #5741741 in Books 2017-02-21Formats: Audiobook, MP3 AudioOriginal language:EnglishRunning time: 15720 secondsBinding: Audio CD | File size: 26.Mb Elmore Leonard : Hombre before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Hombre: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. HombreBy CpheI haven't read anything by the author, nor viewed the movie adaption so can't compare the two however it's no secret that I enjoy a good "western".The story unfolds through the eyes of Carl Allen who is a passenger on a stagecoach that is waylaid by robbers. Among the passengers is John Russell a white man who spent his early years living amongst the Indians.This is a novel of prejudice and greed versus survival and moral integrity. Good versus evil. Loved the setting and the style. The delivery suited the environment the barren and arid desert. Enjoyed the characters presented here, particularly the enigmatic and taciturn John Russell who walks between two worlds.This is more of a longer length novella but well written I thought and offers more than just a novel of the western genre.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. suspense goes on and on between spurts of actionBy Ricky BAn unusual western in that there are lots of taut situations where the waiting and stand-offs are filled with a terse suspense. -

NEO-NOIR / RETRO-NOIR FILMS (1966 Thru 2010) Page 1 of 7

NEO-NOIR / RETRO-NOIR FILMS (1966 thru 2010) Page 1 of 7 H Absolute Power (1997) H Blondes Have More Guns (1995) H Across 110th Street (1972) H Blood and Wine (1996) H Addiction, The (1995) FS H Blood Simple (1985) h Adulthood (2008) H Blood Work (2002) H Affliction (1997) H Blow Out (1981) FS H After Dark, My Sweet (1990) h Blow-up (1967).Blowup H After Hours (1985) f H Blue Desert (1992) F H Against All Odds (1984) f H Blue Steel (1990) f H Alligator Eyes (1990) SCH Blue Velvet (1986) H All the President’s Men (1976) H Bodily Harm (1995) H Along Come a Spider (2001) H Body and Soul (1981) H Ambushed (1998) f H Body Chemistry (1990) H American Gangster (2007) H Body Double (1984) H American Gigolo (1980) f H Bodyguard, The (1992) H Anderson Tapes, The (1971) FSCH Body Heat (1981) S H Angel Heart (1987) H Body of Evidence (1992) f H Another 48 Hrs. (1990) H Body Snatchers (1993) F H At Close Range (1986) H Bone Collector, The (1999) f H Atlantic City (1980) H Bonnie & Clyde (1967) f H Bad Boys (1983) F H Border, The (1982) F H Bad Influence (1990) F H Bound (1996) F H Badlands (1973) H Bourne Identity, The (2002) F H Bad Lieutenant (1992) H Bourne Supremacy, The (2004) h Bank Job, The (2008) H Bourne Ultimatum, The (2007) F H Basic Instinct (1992) H Boyz n the Hood (1991) H Basic Instinct 2 (2006) H Break (2009) H Batman Begins (2005) H Breakdown (1997) F H Bedroom Window, The (1987) F H Breathless (1983) H Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) H Bright Angel (1991) H Best Laid Plans (1999) H Bringing Out the Dead (1999) F H Best -

Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 P.M

DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 p.m. Via Zoom Meeting Platform 1. Call to Order 2. Public Comment 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Consent Agenda Items Approval of March 18, 2021 Regular Meeting Minutes Approval of March 2021 Payroll in the amount of $38,975.80 Approval of March 2021 Vouchers in the amount of $76,398.04 Treasury Reports for March 2021 Balance Sheet for March 2021 (if available) Deletion List – 5116 Items 5. Conflict of Interest 5. Communications 6. Director’s Report 7. Unfinished Business A. Library Opening Update B. Art Policy (N or D) 8. New Business A. Meeting Room Policy (N) B. Election of Officers 9. Other Business 10. Adjournment There may be an Executive Session at any time during the meeting or following the regular meeting. DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Legend: E = Explore Topic N = Narrow Options D = Decision Information = Informational items and updates on projects Parking Lot = Items tabled for a later discussion Current Parking Lot Items: 1. Grand Opening Trustee Lead 2. New Library Public Use Room Naming Jeanne Williams is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting. Topic: Board Meeting Time: Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Pacific Time (US and Canada) Every month on the Third Thu, until Jan 20, 2022, 11 occurrence(s) Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Apr 15, 2021 07:00 PM May 20, 2021 07:00 PM Jun 17, 2021 07:00 PM Jul 15, 2021 07:00 PM Aug 19, 2021 07:00 PM Sep 16, 2021 07:00 PM Oct 21, 2021 07:00 PM Nov 18, 2021 07:00 PM Dec 16, 2021 07:00 PM Jan 20, 2022 07:00 PM Please download and import the following iCalendar (.ics) files to your calendar system. -

Last Name First Name Book Title 1 Abrahams Peter a Perfect Crime 2 Adams Kelly the Silent Heart 3 Adams Kelly Wildfire 4 Adler

Wage Memorial Library Book List (Updated 10/6/2015) # Last Name First Name Book Title 1 Abrahams Peter A Perfect Crime 2 Adams Kelly The Silent Heart 3 Adams Kelly Wildfire 4 Adler Elizabeth In A Heartbeat 5 Adler Elizabeth Legacy Secrets 6 Adler Elizabeth The Last Time I Saw Paris 7 Adler Elizabeth The Secret of the Villa Mimosa 8 Aiken Joan Mortimer Says Nothing 9 Aiken Joan The Haunting of Lamb House 10 Albom Mitch For One More Day 11 Alcott Louisa May A Long Fatal Love Chase 12 Alcott Louisa May Modern Magic 13 Alcott Kate The Dressmaker 14 Alexander Victoria The Prince's Bride 15 Allende Isabel City of the Beasts 16 Anderson Catherine Morning Light 17 Anderson Catherine Phantom Waltz 18 Anderson Catherine Sun Kissed 19 Anderson Susan Head Over Heels 20 Andrews V.C. Celeste 21 Andrews V.C. Dark Angel 22 Andrews V.C. Darkest Hour 23 Andrews V.C. Dawn 24 Andrews V.C. Midnight's Whispers 25 Andrews V.C. Olivia 26 Andrews V.C. Secrets of the Morning 27 Andrews V.C. Twilight's Child 28 Andrews V.C. Web of Dreams 29 Ann Gabhart Angel Sister 30 Archer Jeffrey A Prisoner of Birth 31 Archer Jeffrey Honor Among Thieves 32 Archer Jeffrey Sons of Fortune 33 Arnold Elizabeth Joy Pieces of My Sister's Life 34 Arnold Elizabeth Joy When We Were Friends 35 Arnold Judith One Good Turn 36 Athanas Verne Pursuit 37 Atherton Nancy Aunt Dimity Beats The Devil 38 Atwood Margaret Cat's Eye 39 Auel Jean The Plains of Passage 40 Auel Jean The Shelters of Stone 41 Austen Jane Emma 42 Austen Jane Sense and Sensibility 43 Babson Marian Cover-Up Story 44 Bacher -

WED 5 SEP Home Home Box Office Mcr

THE DARK PAGESUN 5 AUG – WED 5 SEP home home box office mcr. 0161 200 1500 org The Killing, 1956 Elmore Leonard (1925 – 2013) The Killer Inside Me being undoubtedly the most Born in Dallas but relocating to Detroit early in his faithful. My favourite Thompson adaptation is Maggie A BRIEF NOTE ON THE GLOSSARY OF life and becoming synonymous with the city, Elmore Greenwald’s The Kill-Off, a film I tried desperately hard Leonard began writing after studying literature and to track down for this season. We include here instead FILM SELECTIONS FEATURED WRITERS leaving the navy. Initially working in the western genre Kubrick’s The Killing, a commissioned adaptation of in the 1950s (Valdez Is Coming, Hombre and Three- Lionel White’s Clean Break. The best way to think of this season is perhaps Here is a very brief snapshot of all the writers included Ten To Yuma were all filmed), Leonard switched to Raymond Chandler (1888 – 1959) in the manner of a music compilation that offers in the season. For further reading it is very much worth crime fiction and became one of the most prolific and a career overview with some hits, a couple of seeking out Into The Badlands by John Williams, a vital Chandler had an immense stylistic influence on acclaimed practitioners of the genre. Martin Amis and B-sides and a few lesser-known curiosities and mix of literary criticism, geography, politics and author American popular literature, and is considered by many Stephen King were both evangelical in their praise of his outtakes. -

Looking Back: Elmore Leonard Elmore Leonard (B. Oct. 11, 1925

Looking Back: Elmore Leonard Elmore Leonard (b. Oct. 11, 1925), American novelist & screenwriter, died on August 20. – Aug. 20, Leonard was best known for writing crime fiction: fast-paced novels about ex-cons, aspiring kidnappers, gun dealers and loan sharks, and the world-weary lawmen who chase them, often as not shaking their heads over how damned dumb criminals can be. For more about Leonard, his style, and best stuff, follow the link. Leonard was born in New Orleans, but his family moved frequently. In 1934, they settled in Detroit, which remained his home for the rest of his life. After serving in World War Two, he began his writing career while working with an advertising agency. His earliest novels were Westerns, but he went on to specialize in crime fiction and suspense thrillers. He became known as the Dickens of Detroit for the use of that locale in his stories. His best-known works include Get Shorty, Out of Sight, Rum Punch, Glitz, Cuba Libre and Mr. Majestyk. His western stories include ones that became the films Hombre and 3:10 to Yuma. In an article called ‘Why Elmore Leonard Matters,” Laura Williams said “his novels were always expertly plotted and sardonically funny” but what made it “impossible to forget about anything Elmore Leonard ever wrote was his voice.” His writing was short on description but filled with dialogue that “sounds exactly like the way people speak.” Like Mark Twain, Leonard believed he could “tell his readers everything worth knowing about Americans by showing them how we talk. In a 2001 essay, Leonard advised aspiring writers to “go easy on the adverbs” and skip the “hooptedoodle.