Midcentury Futurisms: Expanded Cinema, Design, and the Modernist Sensorium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Wohlstetter's Legacy: the Neo-Cons, Not Carter, Killed

SPECIAL REPORT: NUCLEAR SABOTAGE ALBERT WOHLSTETTER’S LEGACY Wohlstetter was even stranger than the “Dr. Strangelove” depicted in the 1964 movie of that name. An early draft of the film was titled “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” the same title as Wohlstetter’s best-known unclassified work. Here, a still from the film. tives—Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and Zalmay Khalilzad, to name a few. In Wohlstetter’s circle of influence were also Ahmed Chalabi (whom Wohlstetter championed), Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Wash.), Sen. Robert Dole (R- Kan.), and Margaret Thatcher. Wohlstetter himself was a follower of Bertrand Russell, not only in mathematics, but in world outlook. The pseudo-peacenik Russell had called for a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union, after World War II and before the Soviets developed the bomb, as a prelude to his plan for bully- ing nations into a one-world government. Russell, a raving Malthusian, opposed economic development, especially in the Third World. Admirer Jude Wanniski wrote of Wohlstetter in an obituary, “[I]t is no exaggeration, I think, to say that Wohlstetter was the most influential unknown man in the world for the past half century, and easily in the top ten in importance of all men.” “Albert’s decisions were not automat- ically made official policy at the White House,” Wanniski wrote, “but Albert’s The Neo-Cons, Not Carter, genius and his following were such in the places where it counted in the Establishment that if his views were Killed Nuclear Energy resisted for more than a few months, it -

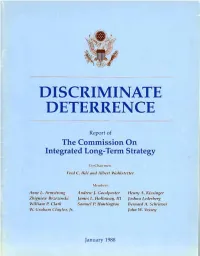

Discriminate Deterrence

DISCRIMINATE DETERRENCE Report of The Commission On Integrated Long-Term Strategy Co -C. I lairmea: Fred C. lkle and Albert Wohlstetter Moither, Anne L. Annsinmg Andrew l. Goodraster flenry /1 Kissinger Zbign ei Brzezinski fames L. Holloway, Ur Joshua Lederberg William P. Clark Samuel P. Huntington Bernard A. Schriever tV. Graham Ciaytor, John W. Vessey January 1988 COMMISSION ON INTEGRATED LONG-TERM STRATEGY January 11. 1988 MEMORANDUM FOR: THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE THE ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AFFAIRS We are pleased to present this final report of Our Commission. Pursuant to your initial mandate, the report proposes adjustments to US. military strategy in view of a changing security environment in the decades ahead. Over the last fifteen months the Commission has received valuable counsel from members of Congress, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Service Chiefs. and the Presdent's Science Advisor, Members of the National Security Council Staff, numerous professionals in the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency, and a broad range of specialists outside the government provided unstinting support. We are also indebted to the Commission's hardworking staff. The Commission was supported generously by several specialized study groups that closely analyzed a number of issues, among them: the security environment for the next twenty years, the role of advanced technology in military systems, interactions between offensive and defensive systems on the periphery of the Soviet Union, and the U.S, posture in regional conflicts around the world. Within the next few months, these study groups will publish detailed findings of their own. -

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Paul Harold Rubinson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War Committee: —————————————————— Mark A. Lawrence, Supervisor —————————————————— Francis J. Gavin —————————————————— Bruce J. Hunt —————————————————— David M. Oshinsky —————————————————— Michael B. Stoff Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War by Paul Harold Rubinson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Acknowledgements Thanks first and foremost to Mark Lawrence for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project. It would be impossible to overstate how essential his insight and mentoring have been to this dissertation and my career in general. Just as important has been his camaraderie, which made the researching and writing of this dissertation infinitely more rewarding. Thanks as well to Bruce Hunt for his support. Especially helpful was his incisive feedback, which both encouraged me to think through my ideas more thoroughly, and reined me in when my writing overshot my argument. I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Smith Richardson Foundation and Yale University International Security Studies for the Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to do the bulk of the writing of this dissertation. Thanks also to the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, and John Gaddis and the incomparable Ann Carter-Drier at ISS. -

How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D

Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Place: The Oval Office, the White House Time: May 1953 The President is in the early months of his first term and he recognizes Soviet military aggression and the How Should the subsequent spread of Communism as the greatest threat to the security of the nation. However, the current costs United States of fighting Communism are skyrocketing, presenting a Confront Soviet significant threat to the nation’s economic well-being. President Eisenhower is concerned that the costs are not Communist sustainable over the long term but he believes that the spread of Communism must be stopped. Expansionism? On May 8, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower has called a meeting in the Solarium of the White House with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Treasury Secretary George M. Humphrey. The President believes that the best way to craft a national policy in a democracy is to bring people together to assess the options. In this meeting the President makes a proposal based on his personal decision-making process—one that is grounded in exhaustive fact gathering, an open airing of the full range of viewpoints, and his faith in the clarifying qualities of energetic debate. Why not, he suggests, bring together teams of “bright young fellows,” charged with the mission to fully vet all viable policy alternatives? He envisions a culminating presentation in which each team will vigorously advocate for a particular option before the National Security Council. -

Preservation by Design: Archives and Records Services at Herman Miller, Inc

Reprint: Business Archives Section Newsletter, 1998 Preservation by Design: Archives and Records Services at Herman Miller, Inc. By Robert W. Viol, Corporate Archivist, Herman Miller, Inc. Who is Herman Miller? Collections and Services departments. Space in the record Herman Miller Inc. is a leading Herman Miller’s corporate archival center has been designed to store multinational manufacturer of holdings have been described by requested documents and furniture, furniture systems and researchers as "awesome" - a accommodate lawyers from both furniture management services. testimonial to the corporate sides of the courtroom. Headquartered in Zeeland, officers, who have generously Michigan, Herman Miller has been provided monetary and moral Get Rid of that Backlog! It Costs a source of major innovation in the support, and to the dozens of men Us Money! residential and office and women, who have contributed Litigation research has environments. The company their effort, time and talent. The demonstrated the urgent need to emphasizes problem solving archives, now located in one of the eliminate the backlog of through design, participate company’s original buildings, uncataloged Herman Miller management, environmental documents the development of publications and non-Herman responsibility and employee stock Herman Miller product from its Miller materials containing third ownership. inception and creation to marketing party endorsements of our product. and distribution. Collections Every growing and viable archives Herman Miller, Inc. began in 1905 include publications, administrative will have a backlog of the as the Star Furniture Company, a records, photography, drawings unprocessed, however, when manufacturer of ornate and blueprints, oral histories, records or publications are reproductions of traditional-style audiovisuals, three dimensional requested as a result of a court home furniture. -

Play and No Work? a 'Ludistory' of the Curatorial As Transitional Object at the Early

All Play and No Work? A ‘Ludistory’ of the Curatorial as Transitional Object at the Early ICA Ben Cranfield Tate Papers no.22 Using the idea of play to animate fragments from the archive of the Institute of Contemporary Arts, this paper draws upon notions of ‘ludistory’ and the ‘transitional object’ to argue that play is not just the opposite of adult work, but may instead be understood as a radical act of contemporary and contingent searching. It is impossible to examine changes in culture and its meaning in the post-war period without encountering the idea of play as an ideal mode and level of experience. From the publication in English of historian Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens in 1949 to the appearance of writer Richard Neville’s Play Power in 1970, play was used to signify an enduring and repressed part of human life that had the power to unite and oppose, nurture and destroy in equal measure.1 Play, as related by Huizinga to freedom, non- instrumentality and irrationality, resonated with the surrealist roots of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London and its attendant interest in the pre-conscious and unconscious.2 Although Huizinga and Neville did not believe play to be the exclusive preserve of childhood, a concern for child development and for the role of play in childhood grew in the post-war period. As historian Roy Kozlovsky has argued, the idea of play as an intrinsic and vital part of child development and as something that could be enhanced through policy making was enshrined within the 1959 Declaration of the -

Freedom in the World 2016 Report

Anxious Dictators, Wavering Democracies: Global Freedom under Pressure FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2016 Highlights from Freedom House’s annual report on political rights and civil liberties. This report was made possible by the generous support of the Smith Richardson Foundation, the Lilly Endowment, the Schloss Family Foundation, and Kim G. Davis. Freedom House also gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the 21st Century ILGWU Heritage Fund, the Reed Foundation, and other private contributors. Freedom House is solely responsible for the content of this report. Freedom in the World 2016 Table of Contents Anxious Dictators, Wavering Democracies: Global Freedom under Pressure 1 Methodology 2 Countries to Watch in 2016 6 Notable Developments in 2015 7 Regional Trends 10 Freedom in the World 2016 Map 12 Freedom in the World 2016 Trend Arrows 18 Freedom in the World 2016 Scores 20 The following people were instrumental in the writing of this essay: Elen Aghekyan, Jennifer Dunham, Bret Nelson, Shannon O’Toole, Sarah Repucci, and Vanessa Tucker. This booklet is a summary of findings for the 2016 edition ofFreedom on the World. The complete analysis including narrative reports on all countries and territories can be found on our website at www.freedomhouse.org. ON THE COVER Refugees and migrants arriving at the Greek island of Lesbos, October 2015. Cover image by Aris Messinis/Getty Images FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2016 Anxious Dictators, Wavering Democracies: Global Freedom under Pressure by Arch Puddington and Tyler Roylance The world was battered in 2015 by overlapping crises that fueled xenophobic sentiment in democratic countries, undermined the economies of states dependent on the sale of natural resources, and led authoritarian regimes to crack down harder on dissent. -

International Design Conference in Aspen Records, 1949-2006

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pg1t6j Online items available Finding aid for the International Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 Suzanne Noruschat, Natalie Snoyman and Emmabeth Nanol Finding aid for the International 2007.M.7 1 Design Conference in Aspen records, 1949-2006 ... Descriptive Summary Title: International Design Conference in Aspen records Date (inclusive): 1949-2006 Number: 2007.M.7 Creator/Collector: International Design Conference in Aspen Physical Description: 139 Linear Feet(276 boxes, 6 flat file folders. Computer media: 0.33 GB [1,619 files]) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Founded in 1951, the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) emulated the Bauhaus philosophy by promoting a close collaboration between modern art, design, and commerce. For more than 50 years the conference served as a forum for designers to discuss and disseminate current developments in the related fields of graphic arts, industrial design, and architecture. The records of the IDCA include office files and correspondence, printed conference materials, photographs, posters, and audio and video recordings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical/Historical Note The International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA) was the brainchild of a Chicago businessman, Walter Paepcke, president of the Container Corporation of America. Having discovered through his work that modern design could make business more profitable, Paepcke set up the conference to promote interaction between artists, manufacturers, and businessmen. -

Download?Doi=10.1.1.104.6035&Rep=Rep1&Type=Pdf>

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Towards a performative aesthetics of interactivity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6w42d6p2 Author Penny, SG Publication Date 2011-12-01 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Fibreculture Journal DIGITAL MEDIA + NETWORKS + TRANSDISCIPLINARY CRITIQUE issue 19 2011: Ubiquity issn: 1449 1443 FCJ-132 Towards a Performative Aesthetics of Interactivity Simon Penny University of California, Irvine Introduction As I write this, at the end of 2010, it is sobering to reflect on the fact that over a couple of decades of explosive development in new media art (or ‘digital multimedia’ as it used to be called), in screen based as well as ‘embodied’ and gesture based interaction, the aesthetics of interaction doesn’t seem to have advanced much. At the same time, interaction schemes and dynamics which were once only known in obscure corners of the world of media art research/ creation have found their way into commodities from 3D TV and game platforms (Wii, Kinect) to sophisticated phones (iPhone, Android). While increasingly sophisticated theoretical analyses (from Manovich, 2002 to Chun, 2008 to Hansen, 2006, more recently Stern, 2011 and others) have brought diverse perspectives to bear, I am troubled by the fact that we appear to have ad- vanced little in our ability to qualitatively discuss the characteristics of aesthetically rich interac- tion and interactivity and the complexities of designing interaction as artistic practice; in ways which can function as a guide to production as well as theoretical discourse. -

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959

LAWRENCE ALLOWAY Pedagogy, Practice, and the Recognition of Audience, 1948-1959 In the annals of art history, and within canonical accounts of the Independent Group (IG), Lawrence Alloway's importance as a writer and art critic is generally attributed to two achievements: his role in identifying the emergence of pop art and his conceptualization of and advocacy for cultural pluralism under the banner of a "popular-art-fine-art continuum:' While the phrase "cultural continuum" first appeared in print in 1955 in an article by Alloway's close friend and collaborator the artist John McHale, Alloway himself had introduced it the year before during a lecture called "The Human Image" in one of the IG's sessions titled ''.Aesthetic Problems of Contemporary Art:' 1 Using Francis Bacon's synthesis of imagery from both fine art and pop art (by which Alloway meant popular culture) sources as evidence that a "fine art-popular art continuum now eXists;' Alloway continued to develop and refine his thinking about the nature and condition of this continuum in three subsequent teXts: "The Arts and the Mass Media" (1958), "The Long Front of Culture" (1959), and "Notes on Abstract Art and the Mass Media" (1960). In 1957, in a professionally early and strikingly confident account of his own aesthetic interests and motivations, Alloway highlighted two particular factors that led to the overlapping of his "consumption of popular art (industrialized, mass produced)" with his "consumption of fine art (unique, luXurious):' 3 First, for people of his generation who grew up interested in the visual arts, popular forms of mass media (newspapers, magazines, cinema, television) were part of everyday living rather than something eXceptional. -

Buckminster Fuller Playboy Interview

Buckminster Fuller the Playboy interview February 1972 a cesc publication Buckminster Fuller - the 1972 Playboy Interview ©1972 Playboy cesc publications, P.O. Box 232, Totnes, Devon TQ9 9DD England Page 2 of 19 Buckminster Fuller - the 1972 Playboy Interview ©1972 Playboy a candid conversation with the visionary architect/inventor/philosopher R. BUCKMINSTER FULLER PLAYBOY: Is there a single statement you could make than the others and that makes him a challenge to the that would express the spirit of your philosophy? speediest and most powerful, and there’s a fight between the two and the one wins disseminates the FULLER: I always try to point one thing out: if we do species. The others can just go hump.’ more with less, our resources are adequate to take care of everybody. All political systems are founded Imagine how this happened with man - man in great on the premise that the opposite is true. We’ve been ignorance, born with hunger, born with the need to assuming all along that failure was certain, that our regenerate, not knowing whether or not he’ll survive. universe was running down and it was strictly you or He begins by observing that the people who eat roots me, kill or be killed as long as it lasted. But now, in and berries very often get poisoned by them, and he our century, we’ve discovered that man can be a sees that the animals that don’t eat those things don’t success on his planet, and this is the great change that get poisoned. -

Brochure Exhibition Texts

BROCHURE EXHIBITION TEXTS “TO CHANGE SOMETHING, BUILD A NEW MODEL THAT MAKES THE EXISTING MODEL OBSOLETE” Radical Curiosity. In the Orbit of Buckminster Fuller September 16, 2020 - March 14, 2021 COVER Buckminster Fuller in his class at Black Mountain College, summer of 1948. Courtesy The Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer / Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. RADICAL CURIOSITY. IN THE ORBIT OF BUCKMINSTER FULLER IN THE ORBIT OF BUCKMINSTER RADICAL CURIOSITY. Hazel Larsen Archer. “Radical Curiosity. In the Orbit of Buckminster Fuller” is a journey through the universe of an unclassifiable investigator and visionary who, throughout the 20th century, foresaw the major crises of the 21st century. Creator of a fascinating body of work, which crossed fields such as architecture, engineering, metaphysics, mathematics and education, Richard Buckminster Fuller (Milton, 1895 - Los Angeles, 1983) plotted a new approach to combine design and science with the revolutionary potential to change the world. Buckminster Fuller with the Dymaxion Car and the Fly´s Eye Dome, at his 85th birthday in Aspen, 1980 © Roger White Stoller The exhibition peeps into Fuller’s kaleidoscope from the global state of emergency of year 2020, a time of upheaval and uncertainty that sees us subject to multiple systemic crises – inequality, massive urbanisation, extreme geopolitical tension, ecological crisis – in which Fuller worked tirelessly. By presenting this exhibition in the midst of a pandemic, the collective perspective on the context is consequently sharpened and we can therefore approach Fuller’s ideas from the core of a collapsing system with the conviction that it must be transformed. In order to break down the barriers between the different fields of knowledge and creation, Buckminster Fuller defined himself as a “Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Scientist,” a scientific designer (and vice versa) able to formulate solutions based on his comprehensive knowledge of universe.