Online Versions of the Goldenrod Handouts Have Color Images & Hot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of California, Irvine an Exploration Into

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE AN EXPLORATION INTO DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY AND APPLICATIONS FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF DANCE EDUCATION THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS In Dance by Carl D. Sanders, Jr. Thesis Committee: Professor Lisa Naugle, PhD, Chair Professor Mary Corey Professor Alan Terricciano 2021 ©2021 Carl D. Sanders, Jr. DEDICATION To My supportive wife Mariana Sanders My loyal alebrijes Koda-Bella-Zen My loving mother Faye and father Carl Sanders My encouraging sister Shawana Sanders-Swain My spiritual brothers Dr. Ras Mikey C., Marc Spaulding, and Marshall King Those who have contributed to my life experiences, shaping my artistry. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS v INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Review of Literature Digital Literacy in Dance 5 CHAPTER 2: Methods Dance Education and Autonomous Exploration 15 CHAPTER 3: Findings Robotics for Dancers 23 CONCLUSION 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 31 APPENDIX: Project Video-Link Archive 36 Robot Engineering Info. Project Equipment List iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my Master of Fine Arts in Dance Thesis Committee Chair Lisa Naugle for her guidance, inspiration, compassion, intellect, enthusiasm, and trust to take on this research by following my instincts as an artist and guiding me as an emerging scholar. I also thank the committee members Professor Mary Corey and Professor Alan Terricciano for their support, encouragement, and advice throughout my research and academic journey. Thank you to the Claire Trevor School of the Arts Dance Department faculty, without your support this thesis would not have been possible;. -

Copyrighted Material

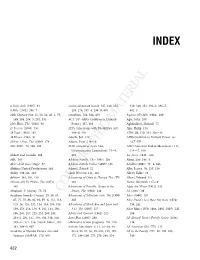

9781405170550_6_ind.qxd 16/10/2008 17:02 Page 432 INDEX 4 Little Girls (1997) 93 action-adventure movie 147, 149, 254, 339, 348, 352, 392–3, 396–7, 8 Mile (2002) 396–7 259, 276, 287–8, 298–9, 410 402–3 20th Century-Fox 21, 30, 34, 40–2, 73, actualities 106, 364, 410 Against All Odds (1984) 289 149, 184, 204–5, 281, 335 ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Agar, John 268 25th Hour, The (2002) 98 Power) 337, 410 Aghdashloo, Shohreh 75 27 Dresses (2008) 353 ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Ahn, Philip 130 28 Days (2000) 293 398–9, 410 AIDS 99, 329, 334, 336–40 48 Hours (1982) 91 Adachi, Jeff 139 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power see 100-to-1 Shot, The (1906) 174 Adams, Evan 118–19 ACT-UP 300 (2007) 74, 298, 300 ADC (American-Arab Anti- AIM (American Indian Movement) 111, Discrimination Committee) 73–4, 116–17, 410 Abbott and Costello 268 410 Air Force (1943) 268 ABC 340 Addams Family, The (1991) 156 Akins, Zoe 388–9 Abie’s Irish Rose (stage) 57 Addams Family Values (1993) 156 Aladdin (1992) 73–4, 246 Abilities United Productions 384 Adiarte, Patrick 72 Alba, Jessica 76, 155, 159 ability 359–84, 410 adult Western 111, 410 Albert, Eddie 72 ableism 361, 381, 410 Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The (TV) Albert, Edward 375 Abominable Dr Phibes, The (1971) 284 Alexie, Sherman 117–18 365 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Algie, the Miner (1912) 312 Abraham, F. Murray 75, 76 COPYRIGHTEDDesert, The (1994) 348 MATERIALAli (2001) 96 Academy Awards (Oscars) 29, 58, 63, Adventures of Sebastian Cole, The (1998) Alice (1990) 130 67, 72, 75, 83, 92, 93, -

Elizabeth Taylor: Screen Goddess

PRESS RELEASE: June 2011 11/5 Elizabeth Taylor: Screen Goddess BFI Southbank Salutes the Hollywood Legend On 23 March 2011 Hollywood – and the world – lost a living legend when Dame Elizabeth Taylor died. As a tribute to her BFI Southbank presents a season of some of her finest films, this August, including Giant (1956), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966). Throughout her career she won two Academy Awards and was nominated for a further three, and, beauty aside, was known for her humanitarian work and fearless social activism. Elizabeth Taylor was born in Hampstead, London, on 27 February 1932 to affluent American parents, and moved to the US just months before the outbreak of WWII. Retired stage actress Sara Southern doggedly promoted her daughter’s career as a child star, culminating in the hit National Velvet (1944), when she was just 12, and was instrumental in the reluctant teenager’s successful transition to adult roles. Her first big success in an adult role came with Vincente Minnelli’s Father of the Bride (1950), before her burgeoning sexuality was recognised and she was cast as a wealthy young seductress in A Place in the Sun (1951) – her first on-screen partnership with Montgomery Clift (a friend to whom Taylor remained fiercely loyal until Clift’s death in 1966). Together they were hailed as the most beautiful movie couple in Hollywood history. The oil-epic Giant (1956) came next, followed by Raintree County (1958), which earned the actress her first Oscar nomination and saw Taylor reunited with Clift, though it was during the filming that he was in the infamous car crash that would leave him physically and mentally scarred. -

The Horror Film Series

Ihe Museum of Modern Art No. 11 jest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Saturday, February 6, I965 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art Film Library will present THE HORROR FILM, a series of 20 films, from February 7 through April, 18. Selected by Arthur L. Mayer, the series is planned as a representative sampling, not a comprehensive survey, of the horror genre. The pictures range from the early German fantasies and legends, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (I9I9), NOSFERATU (1922), to the recent Roger Corman-Vincent Price British series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe, represented here by THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (I96IO. Milestones of American horror films, the Universal series in the 1950s, include THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), FRANKENSTEIN (1951), his BRIDE (l$55), his SON (1929), and THE MUMMY (1953). The resurgence of the horror film in the 1940s, as seen in a series produced by Val Lewton at RR0, is represented by THE CAT PEOPLE (19^), THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (19^4), I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (19*£), and THE BODY SNAT0HER (19^5). Richard Griffith, Director of the Film Library, and Mr. Mayer, in their book, The Movies, state that "In true horror films, the archcriminal becomes the archfiend the first and greatest of whom was undoubtedly Lon Chaney. ...The year Lon Chaney died [1951], his director, Tod Browning,filmed DRACULA and therewith launched the full vogue of horror films. What made DRACULA a turning-point was that it did not attempt to explain away its tale of vampirism and supernatural horrors. -

Folleto Ciclo Del Cine Descargar

ORGANIZA Y COLABORA Y ORGANIZA PABLO DE MARÍA - ALFONSO PALACIO ALFONSO - MARÍA DE PABLO COORDINAN JULIO 2021 JULIO .) BERTO • BERTO (V.O.S castellano en en versión original con subtítulos con original versión en DL: AS-01003-2021 proyectarán se películas las Todas ENTRADA LIBRE HASTA COMPLETAR EL AFORO EL COMPLETAR HASTA LIBRE ENTRADA (CALLE SAN VICENTE, 3 - OVIEDO) - 3 VICENTE, SAN (CALLE MUSEO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE ASTURIAS DE ARQUEOLÓGICO MUSEO SALÓN DE ACTOS DEL ACTOS DE SALÓN 18 HORAS 18 . XVIII siglo el sobre Apuntes tiempo. el en vez una Érase DIÁLOGOS ENTRE EL CINE Y LA PINTURA (XIX). PINTURA LA Y CINE EL ENTRE DIÁLOGOS Diálogos entre el cine y la pintura (XIX). Érase una vez en el tiempo. Apuntes sobre el siglo XVIII Se dice del Siglo XVIII que con su transcurrir se dejó atrás la burguesía urbana ilustrada. El arte neoclásico, clave en la Edad Moderna para iniciar la Edad Contemporánea. este periodo, adopta la racionalidad y la sencillez como Durante esta centuria ocurrieron numerosos hechos elementos, además de tener presente una mirada hacia los que transformaron radicalmente diversas sociedades y valores humanistas y el progreso. Esta selección de pelícu- formas de vivir. Sólo por citar algunos: Primera Revolución las pretende acercar algunos momentos cruciales en la Industrial en Inglaterra, independencia de los Estados historia de este siglo marcado por convulsos cambios que, Unidos de América, estalla la Revolución Francesa, se sin duda, han contribuido a conformar lo que ahora es desarrollan los movimientos indígenas contra las autori- nuestro tiempo presente. dades coloniales en América… Alumbró también este siglo el nacimiento de celebres personajes que contribu- yeron al progreso del pensamiento y de las artes en diferentes ámbitos: Denis Diderot, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Adam Smith, James Cook, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, Jane Austen, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Blake, Francisco de Goya, Jacques-Louis David, Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart o Ludwig van Beethoven. -

Billie Burke

FIVE Series of Lectures and WILL BE EAST WINNER. Plays During Winter II II ?f Vote for Woodrow Wilson New York, Novf. 6. William LAST TIME TONIGHT O. Redfield, secretary of com- Entirely new, yet in keeping with the II merce, visited democratic head- progressive civic spirit of the modern II quarters here today and de- American community is the class room II clared a trip through Indiana theatre movement which will be bitro-duce- d II and Ohio has assured him that to Salem this winter by Prof. President Wilson will be an Wallace MacMurray, of Willamette uni- UNITED STATES easy winner in those states. versity. BILLIE BURKE As an educational factor working for In Chapters 16 and 1 7 of "Gloria's Romance" - the cultural uplift and inspiration oi Far Electors of President and Vice-- I resident of the United States the highest civic ideals this new dra- VOTE FOB FIVE matic movement has been an instantan- Qualifications of eous success wherever introduced. Thil largely due R R., Republican has been to the possibilities 12 BUTLER, Voters In Oregon which its limited is capable Wasco 3 atmosphere II of County of demonstration. Lionel Barrymore In order to give the facts regarding Originating with Percy MacKaye, jj In "The Upheaval" 13 COTTELL, WILLIS I., Republican the qualifications of voters in the na who. is recognized as America's lending of Multnomah County dramatic writer and composer of the 10 o tional election Tuesday the following w set forth in the statutes relat- present, the civic tbeatre, has had a ha rules as phenomenal past Sisters 14 KEADY, W. -

Florenz Ziegfeld Jr

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE ZIEGFELD GIRLS BEAUTY VERSUS TALENT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre Arts By Cassandra Ristaino May 2012 The thesis of Cassandra Ristaino is approved: ______________________________________ __________________ Leigh Kennicott, Ph.D. Date ______________________________________ __________________ Christine A. Menzies, B.Ed., MFA Date ______________________________________ __________________ Ah-jeong Kim, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Jeremiah Ahern and my mother, Mary Hanlon for their endless support and encouragement. iii Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis chair and graduate advisor Dr. Ah-Jeong Kim. Her patience, kindness, support and encouragement guided me to completing my degree and thesis with an improved understanding of who I am and what I can accomplish. This thesis would not have been possible without Professor Christine Menzies and Dr. Leigh Kennicott who guided me within the graduate program and served on my thesis committee with enthusiasm and care. Professor Menzies, I would like to thank for her genuine interest in my topic and her insight. Dr. Kennicott, I would like to thank for her expertise in my area of study and for her vigilant revisions. I am indebted to Oakwood Secondary School, particularly Dr. James Astman and Susan Schechtman. Without their support, encouragement and faith I would not have been able to accomplish this degree while maintaining and benefiting from my employment at Oakwood. I would like to thank my family for their continued support in all of my goals. -

Paramount's 20Th Birthday Jubilee 1931

? ; Ml # ¥ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/paramountOOpara PAMMOUN PUBLIX CORPOfSATIO m. tow* m I opyright, 1931, by Paramount Publix Corporation. Ill rights renerivd. UKOR O Adolph Zukor, eader of the motion picture industry, who first envisioned quality motion picture enter- tainment for the mil- lions as we know it today and whose hand and spirit is most re- sponsible for the mighty progress of Paramount, this book and this pro- gram of pictures are dedicated. Pill 1344 THREE MILESTONE ARAMOUNT'S 20th Birthday Jubilee is of world-wide interest. For the history of Paramountandof Adolph Zukor is the history of the motion picture industry. In 1905, Mr. Zukor at his theatre in Newark, N.J. , introduced the first multiple-reel picture, "The Passion Play". He installed the first organ ever heard in a picture house and a quartet singing"The Rosary". The instant response which these innovations, new and daring for their time, received from the public, the entertainment and genuine inspiration which the crowded houses derived, impressed Mr. Zukor deeply. He resolved to devote his life and fortune to the production and distribution of quality photoplays. The ideal of the modern motion picture and of Paramount was born. His plans brought slowly but surely to fruition, Mr. Zukor in 1911 gave the world "Queen Elizabeth", starring Sarah Bernhardt. The succession of "famous players in famous plays"—James K. Hackett in "The Prisoner of Zenda", Mrs. Fiske in "Tess of the D'Urbervilles" and the rest of the royal line — started. Down through two scores of crowded years Paramount has devoted itself to this ideal first conceived by Adolph Zukor. -

Jack Oakie & Victoria Horne-Oakie Films

JACK OAKIE & VICTORIA HORNE-OAKIE FILMS AVAILABLE FOR RESEARCH VIEWING To arrange onsite research viewing access, please visit the Archive Research & Study Center (ARSC) in Powell Library (room 46) or e-mail us at [email protected]. Jack Oakie Films Close Harmony (1929). Directors, John Cromwell, A. Edward Sutherland. Writers, Percy Heath, John V. A. Weaver, Elsie Janis, Gene Markey. Cast, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Nancy Carroll, Harry Green, Jack Oakie. Marjorie, a song-and-dance girl in the stage show of a palatial movie theater, becomes interested in Al West, a warehouse clerk who has put together an unusual jazz band, and uses her influence to get him a place on one of the programs. Study Copy: DVD3375 M The Wild Party (1929). Director, Dorothy Arzner. Writers, Samuel Hopkins Adams, E. Lloyd Sheldon. Cast, Clara Bow, Fredric March, Marceline Day, Jack Oakie. Wild girls at a college pay more attention to parties than their classes. But when one party girl, Stella Ames, goes too far at a local bar and gets in trouble, her professor has to rescue her. Study Copy: VA11193 M Street Girl (1929). Director, Wesley Ruggles. Writer, Jane Murfin. Cast, Betty Compson, John Harron, Ned Sparks, Jack Oakie. A homeless and destitute violinist joins a combo to bring it success, but has problems with her love life. Study Copy: VA8220 M Let’s Go Native (1930). Director, Leo McCarey. Writers, George Marion Jr., Percy Heath. Cast, Jack Oakie, Jeanette MacDonald, Richard “Skeets” Gallagher. In this comical island musical, assorted passengers (most from a performing troupe bound for Buenos Aires) from a sunken cruise ship end up marooned on an island inhabited by a hoofer and his dancing natives. -

Judy Turns the Objectifying Male Gaze Back on Itself

JUDY O’BRIEN [Maureen O’Hara] (dancing onstage, dress straps rip-male audience members taunt) Go ahead and stare. I'm not ashamed. Go on, laugh; get your money's worth. Nobody's going to hurt you. I know you want me to tear my clothes off so you can look your 50 cents' worth. Fifty cents for the privilege of staring at a girl the way your wives won't let you. What do you suppose we think of you up here? (camera pans l to r well-heeled and ashamed male in tuxedos and reproving female audience members) With your silly smirks your mothers would be ashamed of. It's a thing of the moment for the dress suits to come and laugh at us too. We'd laugh right back at you, only we're paid to let you sit there...and roll your eyes, and make your screamingly clever remarks. What's it for? So you can go home when the show's over, strut before your wives and sweethearts... and play at being the stronger sex for a minute? I'm sure they see through you just like we do. From Dance, Girl, Dance (Dorothy Arzner,1940) Tess Slesinger & Frank Davis (screenplay) Vicki Baum (story) Judy turns the objectifying male gaze back on itself. First 4 have a Hollywood/family connection: Dorothy Arzner’s family owned a Hollywood restaurant frequented by actors and directors Ida Lupino came from a family of British actors Penny Marshall’s Mom was a tap dance teacher, her Dad a director of industrial films and older brother Gary, a TV series creator and successful film director. -

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - December 2013 Hollywood Auction 62, Auction Date

26901 Agoura Road, Suite 150, Calabasas Hills, CA 91301 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - December 2013 Hollywood Auction 62, Auction Date: LOT ITEM PRICE 1 EARLY AMERICAN CINEMA COLLECTION OF (36) PHOTOS. $375 2 PAIR OF RUDOLPH VALENTINO PHOTOS. $325 3 DIE NIBELUNGEN: SIEGFRIED ORIGINAL GERMAN PHOTO FOR FRITZ LANG EPIC. $250 4 OVERSIZE PHOTOGRAPH OF MAE MURRAY BY EDWIN BOWER HESSER. $200 5 OVERSIZE PHOTOGRAPH OF MAE CLARKE FOR FRANKENSTEIN. $325 6 COLLECTION OF (6) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS OF MARY PICKFORD AND OTHER FEMALE STARS. $225 7 VINTAGE LOUISE BROOKS PHOTOGRAPH FROM LOVE ‘EM AND LEAVE ‘EM WITH NOTES IN HER $1,300 HAND. 8 VINTAGE LOUISE BROOKS PHOTOGRAPH FROM ROLLED STOCKINGS WITH NOTES IN HER HAND. $400 9 COLLECTION OF (5) CLARA BOW KEYBOOK PHOTOS FROM (3) FILMS. $200 10 OVERSIZE VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPH OF ERICH VON STROHEIM. $200 11 OVERSIZE CECIL B. DEMILLE PORTRAIT BY IRVING CHIDNOFF. $225 12 OVERSIZE DOUBLE-WEIGHT PORTRAIT OF KAY JOHNSON BY GEORGE HURRELL. $200 13 OVERSIZE PHOTOGRAPH OF JANET GAYNOR WITH SNIPE. $200 14 COLLECTION OF (7) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS OF JOAN CRAWFORD, MARLENE DIETRICH, ANNA $375 MAY WONG, AND LOUISE BROOKS. 15 COLLECTION OF (4) VINTAGE ORIGINAL CAMERA NEGATIVES OF ANNA MAY WONG. $650 16 COLLECTION OF (12) PHOTOS OF JEAN HARLOW. $425 Page 1 of 39 26901 Agoura Road, Suite 150, Calabasas Hills, CA 91301 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - December 2013 Hollywood Auction 62, Auction Date: LOT ITEM PRICE 17 OVERSIZE DOUBLE-WEIGHT (3) PHOTOGRAPHS OF CAROLE LOMBARD. $225 18 COLLECTION OF (7) PHOTOS OF CAROLE LOMBARD. -

Filming Feminist Frontiers/Frontier Feminisms 1979-1993

FILMING FEMINIST FRONTIERS/FRONTIER FEMINISMS 1979-1993 KATHLEEN CUMMINS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN WOMEN’S, FEMINIST AND GENDER STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO November 2014 © Kathleen Cummins, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Filming Feminist Frontiers/Frontier Feminisms is a transnational qualitative study that examines ten landmark feature films directed by women that re-imagined the frontiers of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S through a feminist lens. As feminist feature films they countered Eurocentric and masculinist myths of white settlement and expansionism in the grand narrative tradition. Produced between 1979 and 1993, these films reflect many of the key debates that animated feminist scholarship between 1970 and 1990. Frontier spaces are re-imagined as places where feminist identities can be forged outside white settler patriarchal constructs, debunking frontier myths embedded in frontier historiography and the Western. A central way these filmmakers debunked frontier myths was to push the boundaries of what constitutes a frontier. Despite their common aim to demystify dominant frontier myths, these films do not collectively form a coherent or monolithic feminist revisionist frontier. Instead, this body of work reflects and is marked by difference, although not in regard to nation or time periods. Rather the differences that emerge across this body of work reflect the differences within feminism itself. As a means of understanding these differences, this study examines these films through four central themes that were at the centre of feminist debates during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.