Alcove Spring National Register Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Look at the Donner Party

ETTER FROM CALIFORNIA A New Look at the Donner Party The Native American perspective on a notorious chapter in American history is being reveaied by the excavation and study of a pioneer campsite ULIE M. SCHABLITSKY n late October 1846, an early Donner Party are remembered for out for CaUfornia from Springfield, snowstorm stranded 22 men, cannibalizing their dead in a lastrditch Missouri, in 1846. Hoping to make Iwomen, and chUdren in Alder effort to survive. the Sacramento VaUey by autumn, Creek meadow in CaUfornia's Sierra Almost 10 years ago, I arrived at they feU behind schediile after takr Nevada. The squaU came on so fierce- Alder Creek meadow, a few mues outr ing an untried shortcut through the ly and suddenly that the pioneers had side of Truckee, CaUfomia, with my Great Salt Lake Desert. When an just enough time to erect sleeping excavation codirector KeUy Dixon, of October snowstorm hit, the party was tents and a small structure of pine the University of Montana, and just 100 miles from their destination. trees covered with branches, quUts, a team of coUeagues to search Most of the migrants sought and the rubber coats off their backs. for archaeological evidence of shelter in cabins near Truckee Living conditions were crowded, and that miserable winter. The Lake (now Donner Lake), their wool and flannel clothes were story of the Donner Party is a while the famiUes of brothers useless against leaks and the damp famiUar tale, weU knovm from George and Jacob Donner, ground. As time passed, seasoned the accounts of survivors and their teamsters, and trail wood became so hard to find that rescuers. -

Kansas Fishing Regulations Summary

2 Kansas Fishing 0 Regulations 0 5 Summary The new Community Fisheries Assistance Program (CFAP) promises to increase opportunities for anglers to fish close to home. For detailed information, see Page 16. PURCHASE FISHING LICENSES AND VIEW WEEKLY FISHING REPORTS ONLINE AT THE DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE AND PARKS' WEBSITE, WWW.KDWP.STATE.KS.US TABLE OF CONTENTS Wildlife and Parks Offices, e-mail . Zebra Mussel, White Perch Alerts . State Record Fish . Lawful Fishing . Reservoirs, Lakes, and River Access . Are Fish Safe To Eat? . Definitions . Fish Identification . Urban Fishing, Trout, Fishing Clinics . License Information and Fees . Special Event Permits, Boats . FISH Access . Length and Creel Limits . Community Fisheries Assistance . Becoming An Outdoors-Woman (BOW) . Common Concerns, Missouri River Rules . Master Angler Award . State Park Fees . WILDLIFE & PARKS OFFICES KANSAS WILDLIFE & Maps and area brochures are available through offices listed on this page and from the PARKS COMMISSION department website, www.kdwp.state.ks.us. As a cabinet-level agency, the Kansas Office of the Secretary AREA & STATE PARK OFFICES Department of Wildlife and Parks is adminis- 1020 S Kansas Ave., Rm 200 tered by a secretary of Wildlife and Parks Topeka, KS 66612-1327.....(785) 296-2281 Cedar Bluff SP....................(785) 726-3212 and is advised by a seven-member Wildlife Cheney SP .........................(316) 542-3664 and Parks Commission. All positions are Pratt Operations Office Cheyenne Bottoms WA ......(620) 793-7730 appointed by the governor with the commis- 512 SE 25th Ave. Clinton SP ..........................(785) 842-8562 sioners serving staggered four-year terms. Pratt, KS 67124-8174 ........(620) 672-5911 Council Grove WA..............(620) 767-5900 Serving as a regulatory body for the depart- Crawford SP .......................(620) 362-3671 ment, the commission is a non-partisan Region 1 Office Cross Timbers SP ..............(620) 637-2213 board, made up of no more than four mem- 1426 Hwy 183 Alt., P.O. -

The Great Platte River Road Archway Monument

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 2001 The Great Platte River Road Archway Monument Susan Wunder University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] John R. Wunder University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Wunder, Susan and Wunder, John R., "The Great Platte River Road Archway Monument" (2001). Great Plains Quarterly. 2231. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2231 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. REVIEW ESSAY THE GREAT PLATTE RIVER ROAD ARCHWAY MONUMENT The summer of 2000 marked the grand cation: Honors, a Few Laughs," focused on opening of the Great Platte River Road Arch economic development. Said a local develop way Monument just east of Kearney, Nebraska, ment official and member of the board of the on Interstate SO. Costing approximately $60 private foundation that built the thirty-foot million the site features exhibits on the his high arch, "It's going to serve as a big welcome tory of the American West in the first and mat for the state."2 Even discounting debat only "museum" to straddle an interstate high able geography, Kearney being nearly halfway way. At the 16 July grand opening, former across Nebraska in the center of the Great Nebraska Governor Frank Morrison, a spry Plains, entrance fees-$S.50 per adult, $ 7 per ninety-five years, reminisced before an audi child 3 to 11 and seniors 65 or over-may ence of over six hundred, including both of prove to be a deterrent. -

Cowboywesterncatalog 2018.Pdf

Table of Contents Themes............................................................................................................1-72 Cowboys and the Wild West........................................................................................................... 1-72 New for 2018.......................................................................................................................................................... 1-8 Backlist Titles........................................................................................................................................................9-51 Music and DVD's................................................................................................................................................ 52-61 Posters, Prints, Greeting Cards......................................................................................................................... 62-69 Games and Puzzles.............................................................................................................................................70-71 Edibles.....................................................................................................................................................................72 Price & Product Availability Subject to Change Without Notice Themes Cowboys and the Wild West, New for 2018 101 Things to Do A Night on the Back Page: The with a Dutch Oven Range Best Of Baxter Dutch oven cooking has The cowboy life isn't easy. Black From Western long been popular -

OCTA 36Th Convention, Ogden, Utah August 2018 Recommended Reading List Rails and Trails: Confluence and Consequences at the Crossroads of the West – Jay Buckley

OCTA 36th Convention, Ogden, Utah August 2018 Recommended Reading List Rails and Trails: Confluence and Consequences at the Crossroads of the West – Jay Buckley The auto tour route interpretive guide for Utah provides a brief history of the three national historic trails in northern Utah, directions for getting around, and a listing of interpretive sites on the trails. Other guides for nearby states include Nevada, Idaho, & Wyoming. Chuck Milliken GENERAL HISTORIES OF UTAH AND HER TRAILS Alexander, Thomas G. Utah: The Right Place. Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith, Publishers, 1995. Revised and updated ed. 2007. Crampton, C. Gregory and Steven K. Madsen, In Search of the Spanish Trail: Santa Fe to Los Angeles, 1829- 1848. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith Publishing, 1994. Hafen, LeRoy R. Hafen, The Old Spanish Trail. 1954. Korns, J. Roderic and Dale L. Morgan, West from Fort Bridger, revised and edited by Will Bagley and Harold Schindler. Logan: Utah State University Press, 1994. Will Bagley, S. J. Hensley's Salt Lake Cutoff. Salt Lake City: Oregon-California Trails Association, Utah Crossroads Chapter, 1992. Papanikolas, Helen Z., ed. The Peoples of Utah. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976. Powell, Allan Kent, ed. Utah History Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994. Smart, William B. Old Utah Trails. 1988. NATIVE POPULATIONS, including pre-Fremont, Fremont, Shoshones, Utes Bailey, L. R. Indian Slave Trade in the Southwest. Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1966. Cuch, Forrest S. ed. A History of Utah's American Indians. Salt Lake City: Division of Indian Affairs/Utah Division of State History, 2000. -

Suspended-Sediment Loads, Reservoir Sediment Trap Efficiency, and Upstream and Downstream Channel Stability for Kanopolis and Tuttle Creek Lakes, Kansas, 2008–10

Prepared in cooperation with the Kansas Water Office Suspended-Sediment Loads, Reservoir Sediment Trap Efficiency, and Upstream and Downstream Channel Stability for Kanopolis and Tuttle Creek Lakes, Kansas, 2008–10 Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5187 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover. Upper left: Tuttle Creek Lake upstream from highway 16 bridge, May 16, 2011 (photograph by Dirk Hargadine, USGS). Lower right: Tuttle Creek Lake downstream from highway 16 bridge, May 16, 2011 (photograph by Dirk Hargadine, USGS). Note: On May 16, 2011, the water-surface elevation for Tuttle Creek Lake was 1,075.1 feet. The normal elevation for the multi-purpose pool of the reservoir is 1,075.0 feet. Back cover. Water-quality monitor in Little Blue River near Barnes, Kansas. Note active channel-bank erosion at upper right (photograph by Bill Holladay, USGS). Suspended-Sediment Loads, Reservoir Sediment Trap Efficiency, and Upstream and Downstream Channel Stability for Kanopolis and Tuttle Creek Lakes, Kansas, 2008–10 By Kyle E. Juracek Prepared in cooperation with the Kansas Water Office Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5187 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Kansas River Basin Model

Kansas River Basin Model Edward Parker, P.E. US Army Corps of Engineers Kansas City District KANSAS CITY DISTRICT NEBRASKA IOWA RATHBUN M I HARLAN COUNTY S S I LONG S S I SMITHVILLE BRANCH P TUTTLE P CREEK I URI PERRY SSO K MI ANS AS R I MILFORD R. V CLINTON E WILSON BLUE SPRINGS R POMONA LONGVIEW HARRY S. TRUMAN R COLO. KANOPOLIS MELVERN HILLSDALE IV ER Lake of the Ozarks STOCKTON KANSAS POMME DE TERRE MISSOURI US Army Corps of Engineers Kansas City District Kansas River Basin Operation Challenges • Protect nesting Least Terns and Piping Plovers that have taken residence along the Kansas River. • Supply navigation water support for the Missouri River. • Reviewing requests from the State of Kansas and the USBR to alter the standard operation to improve support for recreation, irrigation, fish & wildlife. US Army Corps of Engineers Kansas City District Model Requirements • Model Period 1/1/1920 through 12/31/2000 • Six-Hour routing period • Forecast local inflow using recession • Use historic pan evaporation – Monthly vary pan coefficient • Parallel and tandem operation • Consider all authorized puposes • Use current method of flood control US Army Corps of Engineers Kansas City District Model PMP Revisions • Model period from 1/1/1929 through 12/30/2001 • Mean daily flows for modeling rather than 6-hour data derived from mean daily flow values. • Delete the requirement to forecast future hydrologic conditions. • Average monthly lake evaporation rather than daily • Utilize a standard pan evaporation coefficient of 0.7 rather than a monthly varying value. • Separate the study basin between the Smoky River Basin and the Republican/Kansas River Basin. -

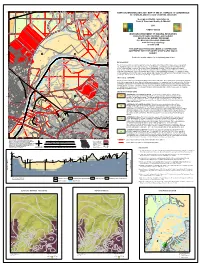

ST. CHARLES 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qslt 0 5 4 ST

90°22'30"W 90°30'00"W 90°27'30"W 90°25'00"W R 5 E R 6 E 38°52'30"N 38°52'30"N 31 32 33 34 35 36 31 35 SURFICIAL MATERIAL GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE ST. CHARLES 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qslt 0 5 4 ST. CHARLES AND ST. LOUIS COUNTIES, MISSOURI 0 45 Qslt 2 Geology and Digital Compilation by 0 45 Qtd David A. Gaunt and Bradley A. Mitchell Qcly «¬94 3 5 6 5 4 2011 Qslt Qtd Qtd Qtd 1 Graus «¬94 Lake OFM-11-593-GS 6 «¬H Qtd 6 Croche 9 10 MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 8 7 s DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND LAND SURVEY ai ar 7 M GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROGRAM Qslt Qtd P.O. BOX 250, ROLLA MO 65402-0250 12 www.dnr.mo.gov/geology B «¬ Qslt 573-368-2100 7 13 THIS MAP WAS PRODUCED UNDER A COOPERATIVE 0 5 AGREEMENT WITH THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL 4 18 38°50'00"N 38°50'00"N SURVEY Qtd Permission must be obtained to visit privately owned land Qslt Qslt PHYSIOGRAPHY 0 5 4 St. Charles County D St. Louis County The St. Charles quadrangle includes part of the large floodplain of the Missouri River and loess covered uplands. N 500 550 A L The floodplain is up to five miles wide in this area. The quadrangle lies within the Dissected Till Plains Section 50 S 5 I 45 6 0 0 0 of the Central Lowland Province of the Interior Plains Physiographic Division. -

Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications of the US Geological Survey US Geological Survey 2005 Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History Steven M. Condon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgspubs Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Condon, Steven M., "Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History" (2005). Publications of the US Geological Survey. 22. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgspubs/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications of the US Geological Survey by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South- Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History Professional Paper 1706 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geologic Studies of the Platte River, South-Central Nebraska and Adjacent Areas—Geologic Maps, Subsurface Study, and Geologic History By Steven M. Condon Professional Paper 1706 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Version 1.0, 2005 This publication and any updates to it are available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/pp1706/ Manuscript approved for publication, March 3, 2005 Text edited by James W. Hendley II Layout and design by Stephen L. -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

Donner Memorial State Park

Donner Memorial State Park GENERAL PLAN Volume 1 of 2 Approved by the State Park and Recreation Commission April 5, 2003 VOLUME 1 This is Volume 1 of the Final General Plan for Donner Memorial State Park. It contains the Summary of Existing Conditions; Goals and Guidelines for park development and use; Environmental Analysis (in compliance with Article 9 and Article 11 Section 15166 of the California Environmental Quality Act); and Maps, Matrices, and Appendices relating to the General Plan. Volume 2 of the Final General Plan contains the Comments and Responses (comments received during public review of the General Plan and DPR response to those comments); and the Notice of Determination (as filed with the State Office of Planning and Research), documenting the completion of the CEQA compliance requirements for this project. Together, these two volumes constitute the Final General Plan for Donner Memorial State Park. COPYRIGHT This publication, including all of the text and photographs in it, is the intellectual property of the Department of Parks and Recreation and is protected by copyright. GENERAL PLANNING INFORMATION If you would like more information about the general planning process used by the Department or have questions about specific general plans, contact: General Planning Section California State Parks P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296 - 0001 All Photographs Copyright California State Parks DONNER MEMORIAL STATE PARK GENERAL PLAN Approved April 5, 2003 State Clearinghouse #2001102069 Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor Mike Chrisman Secretary for Resources Ruth Coleman Director of California State Parks State of California The Resources Agency California State Parks P.O. -

Big Blue River Watershed Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus and Ph

KANSAS-LOWER REPUBLICAN BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Waterbody/Assessment Unit: Big Blue River Watershed Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus and pH 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Lower Big Blue, Lower Little Blue Counties: Marshall, Washington HUC8: 10270205 HUC10 (12): 01 (03, 04) 02 (01, 02, 03, 04) 05 (01, 02, 03) HUC8: 10270207 HUC10 (12): 06 (06) Ecoregion: Smoky Hills (27a), Flint Hills (28a), and Loess and Glacial Drift Hills (47i) Drainage Are a: Approximately 383 square miles (mi2) Water Quality Limited Segments Covered Under TMDL (designated uses for main stem and tributary segments are detailed in Table 1): Main Stem Segment Tributaries Tributaries HUC8: 10270205 Big Blue R (21) Deer Cr (36) Scotch Cr (38) Bommer Cr (40) Elm Cr, North (41) Mission Cr (22) Murdock Cr (42) Big Blue R (20) Horseshoe Cr (26) Raemer Cr (33) Indian Cr (37) Meadow Cr (34) Little Indian Cr (35) Big Blue R (18) Dutch Cr (44) Hop Cr (43) Spring Cr (19) Schell Cr (45) Lily Cr (39) Big Blue R (17) Elm Cr (46) HUC8: 10270207 Fawn Cr (45) 1 Table 1. Designated uses for main stem and tributary segments in the watershed (Kansas Department of Health and Environment, 2013). Stream Segment Expected Contact Domestic Food Ground Industrial Irrigation Livestock # Aquatic Recreation Supply Procurement Water Water Use Use Watering Life Recharge Use HUC8: 10270205 Big Blue R 17 E B X X X X X X Elm Cr 46 E b X X X X X X Big Blue R 18 E B X X X X X X Dutch Cr 44 E b O O O O O O Hop Cr 43 E b O X X O X X Spring Cr 19 E B X X X X X X Schell