After the Storm: Voices from the Delta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF BANKING AND FINANCE PROGRAMME INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE (CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION) KHET KHET MYAT NWAY (MBF 4th BATCH – 30) DECEMBER 2018 INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION A thesis summited as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the Degree of Master of Banking and Finance (MBF) Supervised By : Submitted By: Dr. Daw Tin Tin Htwe Ma Khet Khet Myat Nway Professor MBF (4th Batch) - 30 Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ABSTRACT This study aims to identify the influencing factors on farms’ performance in Bogale Township. This research used both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected by interviewing with farmers from 5 groups of villages. The sample size includes 150 farmers (6% of the total farmers of each village). Survey was conducted by using structured questionnaires. Descriptive analysis and linear regression methods are used. According to the farmer survey, the household size of the respondent is from 2 to 8 members. Average numbers of farmers are 2 farmers. Duration of farming experience is from 11 to 20 years and their main source of earning is farming. Their living standard is above average level possessing own home, motorcycle and almost they owned farmland and cows. The cultivated acre is 30 acres maximum and 1 acre minimum. Average paddy yield per acre is around about 60 bushels per acre for rainy season and 100 bushels per acre for summer season. -

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE of MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ;

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE OF MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ; © 2018, INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly credited. Cette œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), qui permet l’utilisation, la distribution et la reproduction sans restriction, pourvu que le mérite de la création originale soit adéquatement reconnu. IDRC Grant/ Subvention du CRDI: 108748-001-Climate and nutrition smart villages as platforms to address food insecurity in Myanmar 33 IDRC \CRDl ..m..»...u...».._. »...m...~ c.-..ma..:«......w-.«-.n. ...«.a.u CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE PROFILE Ma Sein Village Bogale Township, Ayeyarwaddy Region 2 Climate Smart Village Profile Introduction Myanmar is the second largest country in Southeast Asia bordering Bangladesh, Thailand, China, India, and Laos. It has rich natural resources – arable land, forestry, minerals, natural gas, freshwater and marine resources, and is a leading source of gems and jade. A third of the country’s total perimeter of 1,930 km (1,200 mi) is coastline that faces the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. The country’s population is estimated to be at 60 million. Agriculture is important to the economy of Myanmar, accounting for 36% of its economic output (UNDP 2011a), a majority of the country’s employment (ADB 2011b), and 25%–30% of exports by value (WB–WDI 2012). -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

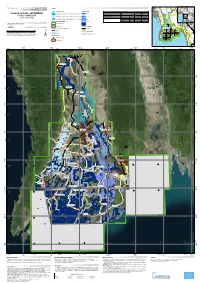

Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area Delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R

Nepal (!Loikaw GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR130 I Legend r n r India China e Product N.: 16IRRAWADDYDELTA, v2, English Magway a Rakhine w Bangladesh e a w l d a Vietnam Crisis Information Hydrology Consequences within the AOI on 09, 10, 11/08/2015 d Myanmar S Affected Total in AOI y Nay Pyi Taw Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R ha 428922,1 i v Laos Flooded area e ^ r S Flood - 01/08/2015 Flooded Area delineation 10/08/2015 23:49 UTC Stream Estimated population Inhabitants 4252141 11935674 it Bay of ( to Settlements Built-up area ha 35491,8 75542,0 A 10 Bago n Bengal Thailand y g Delineation Map e Flooded Area delineation 09/08/2015 11:13 UTC Lake y P Transportation Railways km 26,0 567,6 a Cambodia r i w Primary roads km 33,0 402,1 Andam an n a Gulf of General Information d Sea g Reservoir Secondary roads km 57,2 1702,3 Thailand 09 y Area of Interest ) Andam an Cartographic Information River Sea Missing data Transportation Bay of Bengal 08 Bago Tak Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 07 1:600000 Ayeyarwady Yangon (! Administrative boundaries Railway Kayin 0 12,5 25 50 Region km Primary Road Pathein 06 04 11 12 (! Province Mawlamyine Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N map coordinate system Secondary Road 13 (! Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Settlements 03 02 01 ! Populated Place 14 15 Built-Up Area Gulf of Martaban Andaman Sea 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 94°10'0"E 94°35'0"E 95°0'0"E 95°25'0"E 95°50'0"E 96°15'0"E 96°40'0"E 97°5'0"E N " 0 ' 5 -

Myanmar-Government-Projects.Pdf

Planned Total Implementing Date Date Last Project Project Planned Funding Financing Tender Developer Sector Sr. Project ID Description Expected Benefits End Project Government Ministry Townships Sectors MSDP Alignment Project URL Created Modified Title Status Start Date Sources Information Date Name Categories Date Cost Agency The project will involve redevelopment of a 25.7-hectare site The project will provide a safe, efficient and around the Yangon Central Railway Station into a new central comfortable transport hub while preserving the transport hub surrounded by housing and commercial heritage value of the Yangon Central Railway Station amenities. The transport hub will blend heritage and modern and other nearby landmarks. It will be Myanmar’s first development by preserving the historic old railway station main ever transit-oriented development (TOD) – bringing building, dating back in 1954, and linking it to a new station residential, business and leisure facilities within a constructed above the rail tracks. The mixed-use development walking distance of a major transport interchange. will consist of six different zones to include a high-end Although YCR railway line have been upgraded, the commercial district, office towers, condominiums, business image and performance of existing railway stations are hotels and serviced apartments, as well as a green park and a still poor and low passenger services. For that railway museum. reason, YCR stations are needed to be designed as Yangon Circular Railway Line was established in 1954 and it has attractive, comfortable and harmonized with city been supporting forYangon City public transportation since last development. On the other hand, we also aligned the 60 years ago. -

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

Social Assessment for Ayeyarwady Region and Shan State

AND DEVELOPMENT May 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SOCIAL ASSESSMENT FOR AYEYARWADY REGION AND SHAN STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition 1 Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement May 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... 10 List of BOXES ................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Introduction and Background....................................................................................................... 11 1 Objectives of the Social Assessment ................................................................................................11 2 Project Description ..........................................................................................................................11 3 Relevant Country and Sector Context..............................................................................................12 3.1 -

Cyclone Nargis

Emergency appeal n° MDRMM002 Myanmar: GLIDE n° TC-2008-000057-MMR Operations update n° 6 12 May 2008 Cyclone Nargis Desperate conditions: this family seeks a modicum of shelter in awful conditions nine days after they lost their home. (International Federation). Period covered by this Update: first six days since appeal was launched Appeal target (current): CHF 6,290,909 (USD 5.9 million or EUR 3.86 million); <click here to view the attached Emergency Appeal Budget> Appeal coverage: This appeal is already well covered. Initial planning is underway in-country as the International Federation’s ability to scale up effectively increases to support Myanmar Red Cross Society and to meet the huge needs. A revised appeal will be issued by the end of the week. This appeal will significantly scale up the plan of action and give a stronger indication of work within priority areas but there is still a considerable need to remain flexible in the face of the challenges around this operation. 2 <click here to link to the current donor response list> <click here to link to contact details > Appeal history: • This preliminary emergency appeal was launched on 6 May 2008 for CHF 6,290,909 (USD 5.9 million or EUR 3.86 million) for six months to assist 30,000 families. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 200,000 has been allocated from the Federation’s DREF. Summary: A significant shift in strategic thinking has occurred to try to navigate some of the main issues facing this operation. Principal among these is a proposal to recruit and train local people in Yangon in basic relief management who would then move to ten agreed hubs in the delta (various university students have already expressed an interest). -

UNDP Myanmar Responds to Cyclone Nargis

UNDP Myanmar responds MATTERS OF FACT to Cyclone Nargis • 40 UNDP and its implementing partner NGO PACT offices in the Ayeyarwady Delta UNDP moved into action within 24 hours after Cyclone • 23 field teams active in the worst affected areas Nargis hit Myanmar on 2-3 May. The storm carved a • 500 national staff and project personnel working in the path of destruction that left 133,653 dead or missing delta and being mobilized for Cyclone Nargis response and 2.4 million severely affected by the crisis. operations • 5 UNDP offices functioning as ‘base camp’ for UN The cyclone’s 120-mile per hour winds and resulting organizations and international NGOs delivering to, and storm surge were particularly devastating in the working in Bogale, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ayeyarwady Delta, where entire villages were flattened. Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat • 2.4 million people severely affected by Cyclone UNDP is the only UN organization with field offices Nargis across Myanmar located in the region, which, prior to the cyclone was • 1.4 million people affected in the Ayeyarwady delta, home to seven million people. UNDP staff and families the hardest hit region of Myanmar experienced the natural disaster first-hand, as did those • 43,241 estimated total beneficiaries from UNDP coordinated relief efforts as of 21 May who work for partner non-governmental organization (NGO) PACT, which lost five of its project personnel. Supporting relief efforts: UNDP sent rotating teams UNDP has 40 functioning field offices in the delta and of national staff to work with and relieve its field staff in current field staff strength of more than 500 five of the affected townships – Bogale, experienced national staff and project personnel, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat – including those of PACT. -

Water Infrastructure Development and Policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 12 | Issue 3 Ivars, B. and Venot, J.-P. 2019. Grounded and global: Water infrastructure development and policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar. Water Alternatives 12(3): 1038-1063 Grounded and Global: Water Infrastructure Development and Policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar Benoit Ivars University of Köln, Germany; [email protected] Jean-Philippe Venot UMR G-EAU, IRD, Univ Montpellier, France; and Royal University of Agriculture, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; jean- [email protected] ABSTRACT: Seen as hotspots of vulnerability in the face of external pressures such as sea level rise, upstream water development, and extreme weather events but also of in situ dynamics such as increasing water use by local residents and demographic growth, deltas are high on the international science and development agenda. What emerges in the literature is the image of a 'global delta' that lends itself to global research and policy initiatives and their critique. We use the concept of 'boundary object' to critically reflect on the emergence of this global delta. We analyse the global delta in terms of its underpinning discourses, narratives, and knowledge generation dynamics, and through examining the politics of delta-oriented development and aid interventions. We elaborate this analytical argument on the basis of a 150-year historical analysis of water infrastructure development and policymaking in the Ayeyarwady Delta, paying specific attention to recent attempts at developing an Integrated Ayeyarwady Delta Strategy (IADS) and the role that the development of this strategy has played in the 'making' of the Ayeyarwady Delta as a global delta. -

Cases Related to COVID-19 Pandemic

Cases Related to COVID-19 Pandemic The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) has documented cases in relation to the COVID-19 Pandemic. According to our documentation from March to end of April, a total of 670 people have been charged and punished in Burma during the pandemic. The detailed information is shown below: (455) under Section 188 of the Penal Code and (18) under Section 18 of the Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases Law are facing trials and serving sentences for failing abide-by the night curfew In addition, (166) are charged and convicted under Section 25, 26, 26(a), 27, 28(b), 30(a) (b) of the Natural Disaster Management Law and Section 15 and 18 of the Prevention and Control of Communicable Diseases Law and (2) are awaiting trial inside and outside prison under Section 16(c) of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Law for failing to comply with the quarantine measures. Moreover, (3) under Sections 325,114 of the Penal Code, (4) under Sections 294, 506, 353, 324 of the Penal Code, (11) under Sections 333, 323, 427, 506, 114 of the Penal Code, (1) under Sections 333, 506, 294 of the Penal Code, (1) under Section 19 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law, (2) under Sections 336, 353, 294, 114 of the Penal Code, (1) under Sections 353, 506, 323, 294 of the Penal Code and (3) under Section 295(a) of the Penal Code are awaiting trial inside and outside prison and (2) under Section 47 of the Police Act and (1) under Section 5(1) of the Foreign Registration Act are serving the sentences for contravention of specified orders.