Introduction to Graceland Cemetery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

Collection Overview

Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 Collection Overview The Gerber/Hart archives focuses its collections on gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer life in the Chicago metropolitan area and the Midwest. It contains over 150 collections of historically significant personal manuscripts, photographs, audiovisual recordings, and organizational records. These collections include unpublished material such as letters, diaries, and scrapbooks documenting the lives of both average people and community leaders. They also include the records of many community organizations, businesses, and political campaigns. This guide is intended to serve as a preliminary research tool that provides a brief description of holdings with basic information on size, inclusive dates, types of records, and broad subject areas. Guide Contents List of Collections..............................................................................................................................................2 Collections Descriptions....................................................................................................................................6 Name Index......................................................................................................................................................26 Topical Index...................................................................................................................................................34 1 Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 List of Collections -

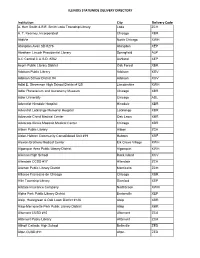

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

American Bronze Co., Chicago

/American j^ronze C^- 41 Vai| pUreii S^ree^, - cHICAGO, ILLS- Co.i Detroit. ite arid <r\ntique t^ponze JVlonumer|tal Wopk.. Salesroom: ART FOUNDRY. II CHICAGO. H. N. HIBBARD, Pres't. PAUL CORNELL, Vice-Pres't, JAS, STEWART, Treas, R J, HAIGHT, Sec'y, THE HEMRT FRAXCIS du POJ^ WIXrERTHUR MUSEUM LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/whiteantiquebronOOamer Tillr rr|ore prominent cemeteries in this country are noW arranged or) what is l<;noWn as the LfavVn I'lan, which gives the grounds a park-like appearaqce, n]ore in harmony With the impulse of our natures to make tl^ese lastresting places beautiful; in striking contrast to the gloomy burying places of olden times. pences, hedges, curbiqg aqd enclosures of all kinds are prol]ibited and tl^e money formerly expended for such fittings is invested in a central monu- ment, theicby enabling the lot oWner to purchase a better niemorial tl]an could otherwise haVe been afforded. (Corner posts are barely Visible aboVe the surface of the ground, and markers at the head of graVes are allowed ' only a feW inches higher, thus preserving the beautiful landscape effect. JViaiiy of tl]e n"ionum|ents novV being erected, and several that are illustrated in this pamphlet, bear feW, if aiw, fcmiily records, thus illustrating the growing desire to provide a fan]ily resting place and an enduring n-jonu- rqent. Without deferring it until there Fjos been a death in the family, as has been the custom in tlie past. -

Fall 2005.Pub

The Society of Architectural Historians News Missouri Valley Chapter Volume XI Number 3 Fall 2005 Letter Simonds is often overlooked by historians, in contrast HANNIBAL’S RIVERVIEW PARK: 1 to contemporaries such as Jens Jensen. While Jensen A PUBLIC LANDSCAPE was an able promoter who wrote manifestos for prairie- BY O. C. SIMONDS inspired designs, Simonds was self-effacing and wrote By Karen Bode Baxter and Matthew Cerny books, such as Landscape-Gardening, which were with help from Mandy Ford and Sara Bularzik practical and instructive but not philosophical.2 Riverview Park covers 465 acres of high bluffs and Simonds’ professional training began as a student of deep draws overlooking the Mississippi River at the civil engineering at the University of Michigan in 1874. northern edge of Hannibal in Marion County, Missouri. He studied architecture under William LeBaron Jenney The park owes its existence to the generosity of Wilson for two years until the architecture program closed, B. Pettibone, who created and opened the park in 1909. then went to work for Jenney’s firm in Chicago after Pettibone sought strictly to respect the natural appear- completing his engineering degree in 1878. Jenney ance of the land and to avoid all traces of artificiality. assigned Simonds the responsibility for draining the To do this, he turned to one of the leading proponents low-lying marsh at Graceland Cemetery on the north of the prairie style of landscape design, Ossian Cole side of Chicago. Simonds. With his advanced understanding of native Midwestern plants, Simonds was able to take bare land Bryan Lathrop, a prominent Chicago speculator and that had been abused by farming and turn it into an en- philanthropist (whose 1892 house by McKim, Mead & hanced representation of what most people now assume White still stands at 120 East Bellevue Place), repre- to be a native forest. -

July 2019–June 2020 Annual Report 2019-2020 Year in Review Table of Contents

JULY 2019–JUNE 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 YEAR IN REVIEW TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Chair’s Message 5 President’s Message 7 This is Chicago Campaign Our Mission 9 Institutional News To share Chicago stories, serving as a hub of scholarship and 12 Public Engagement learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. 16 Spring Quarantine 19 Educational Initiatives 21 Board of Trustees A New Look In July 2020, the Chicago History Museum (CHM) debuted a new 22 Honor Roll of Donors brand platform comprising strategic statements, a master narrative, 38 Donors to the Collection and visual elements. Our new logo, color palette, and typography 40 Treasurer’s Report will serve as an ongoing touchstone for brand communications 42 Volunteers and expression as we help people make meaningful and personal 43 Staff connections to history. 1601 North Clark Street The Chicago History Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago, Illinois 60614-6038 Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago. 312.642.4600 CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM 2 2019–20 Annual Report 2020 ANNUAL REPORT CHAIR’S MESSAGE Your Chicago History Museum has never been more museum swung into full gear. On the very first day of the relevant or more essential than it is today. During quarantine, “Chicago History at Home” was born as a daily FY 2020, we marked many achievements, confronted the series making use of our digital content. As the quarantine unprecedented challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, and went on, our education team designed daily activities for continued to address the deeply rooted legacy of racial children, families, and teens to supplement the Museum’s discrimination in our society. -

Custom Report for Wilhelm F Kriesel

Custom Report for Wilhelm F Kriesel ( Per her death cert, she is to be buried at Roselawn ) Name: Marie Grace 'Bessie' Wilkey Burial: 1940 in McAllen, Hidalgo, Texas, USA; ( Per her death cert, she is to be buried at Roselawn ) AB-Grimshaw - Grimshaw Women's Institute Cemetery Name: Joseph Funk Burial: 1975 in Grimshaw, Peace, Alberta, Canada; AB-Grimshaw - Grimshaw Women's Institute Cemetery AL-Grand Bay - Grand Bay Cemetery Name: Dalores Elaine Johnson Burial: 1995 in Grand Bay, Mobile, Alabama, USA; AL-Grand Bay - Grand Bay Cemetery Name: Houndle Lavalle Lindsey Burial: 1982 in Grand Bay, Mobile, Alabama, USA; AL-Grand Bay - Grand Bay Cemetery AZ.National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona - Sec 53 Site 345 Name: Charles Francis Perry Burial: 2007 in Phoenix, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ.National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona - Sec 53 Site 345 AZ-Buckeye - Louis B Hazelton Memorial Cemetery Name: Robert Lyle Reed Burial: 2009 in Buckeye, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ-Buckeye - Louis B Hazelton Memorial Cemetery AZ-Show Low - Show Low Cemetery Name: Archie Leland Prust Burial: 2006 in Show Low, Navajo, Arizona, USA; AZ-Show Low - Show Low Cemetery AZ-Sun City - Sunland Memorial Park Name: George E Lehman Burial: 2000 in Sun City, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ-Sun City - Sunland Memorial Park Name: Ruth Edna Roerig Burial: 1993 in Sun City, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ-Sun City - Sunland Memorial Park AZ-Tucson - East Lawn Palms Cemetery and Mortuary Name: Inez Brown Burial: 2014 in Tucson, Pima, Arizona, USA; AZ-Tucson - East Lawn Palms Cemetery and -

Printed U.S.A./November 1984 a Contemporary View of the Old Chicago Water Tower District

J,, I •CITY OF CHICAGO Harold Washington, Mayor COMMISSION ON CHICAGO HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL LANDMARKS Ira]. Bach, Chairman Ruth Moore Garbe, Vice-Chairman Joseph Benson, Secretary John W. Baird Jerome R. Butler, Jr. William M. Drake John A. Holabird Elizabeth L. Hollander Irving J. Markin William M. McLenahan, Director Room 516 320 N. Clark Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 (312) 744-3200 Printed U.S.A./November 1984 A contemporary view of the Old Chicago Water Tower District. (Bob Thall, photographer) OLD CHICAGO WATER TOWER DISTRICT Bounded by Chicago Avenue, Seneca and Pearson streets, and Michigan Avenue. The district is com prised of the Old Chicago Water Tower, Chicago Avenue Pumping Station, Fire Station of Engine Company No. 98, Seneca and Water Tower parks. The district was designated a Chicago Landmark by the City Council on October 6, 1971; the district was expanded by the City Council on June 10, 1981. Standing on both north corners of the prominent inter section of Michigan and Chicago avenues are two important and historic links with the past, the Old Chicago Water Tower and the Chicago Avenue Pumping Station. The Old Water Tower, on the northwest corner, has long been recog nized as Chicago's most familiar and beloved landmark. The more architecturally interesting of the two structures, it is no longer functional and has not been since early in this century. The Pumping Station, the still functioning unit of the old waterworks, stands on the northeast corner. When the waterworks were constructed at this site in the late 1860s, there was no busy Michigan Avenue separating the adjoining picturesque buildings. -

Surname First JMA# Death Date Death Location Burial Location Photo

Surname First JMA# Death date Death location Burial Location Photo (MNU) Emily R45511 December 31, 1963 California? Los Molinos Cemetery, Los Molinos, Tehama County, California (MNU) Helen Louise M515211 April 24, 1969 Elmira, Chemung County, New York Woodlawn National Cemetery, Elmira, Chemung County, New York (MNU) Lillian Rose M51785 May 7, 2002 Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery, Boulder City, Nevada (MNU) Lois L S3.10.211 July 11, 1962 Alhambra, Los Angeles County, California Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, Los Angeles County, California Ackerman Seymour Fred 51733 November 3, 1988 Whiting, Ocean County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackerman Abraham L M5173 October 6, 1937 Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackley Alida M5136 November 5, 1907 Newport, Herkimer County, New York Newport Cemetery, Herkimer, Herkimer County, New York Adrian Rosa Louise M732 December 29, 1944 Los Angeles County, California Fairview Cemetery, Salida, Chaffee County, Colorado Alden Ann Eliza M3.11.1 June 9, 1925 Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Rose Hill Cemetery, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Alexander Bernice E M7764 November 5, 1993 Whitehall, Pennsylvania Walton Town and Village Cemetery, Walton, Delaware County, New York Allaben Charles Moore 55321 April 12, 1963 Binghamton, Broome County, New York Vestal Hills Memorial Park, Vestal, Broome County, New York Yes Allaben Charles Smith 5532 December 12, 1917 Margaretville, -

UPTOWN and ANDERSONVILLE Bike Tour, Sunday June Twentynine, Two Thousand Eight

UPTOWN AND ANDERSONVILLE bike tour, sunday june twentynine, two thousand eight. All Content Copyright © 2007-2008 Big Shoulders Realty, LLC. All Rights Reserved. uptown and andersonville bike tour Our Route, Part One uptown and andersonville bike tour Tour Part One – turn by turn instructions 1. Start at Graceland Cemetery, 4001 N Clark 22. Turn right heading north on Racine 2. Proceed east on Irving Park 23. Take a SHARP right, heading southeast on Broadway 3. Turn left heading north on Sheridan 24. Turn right heading west on Montrose 4. Take a SHARP right heading south on Broadway 25. Turn right heading north on Clifton, which curves to the left 5. Turn left, heading east on Irving Park 26. Turn left heading south on Racine 6. Turn left, heading north on Marine Dr. 27. Turn right heading west on Montrose 7. Turn left, heading west on Hutchinson 28. Turn right heading north on Beacon 8. Turn left, heading south on Hazel 29. Turn left, heading west on Leland 9. Turn left, heading east on Buena 30. Turn left, heading south on Dover 10. Turn left, heading north on Clarendon 31. Turn right, heading west on Wilson 11. Turn right heading east on Montrose 32. Turn right, heading north on Ashland 12. Stay on Montrose until after you cross under Lake Shore Drive. 33. Turn left, heading west on Lawrence 13. Then veer left onto the bike path. 34. Turn left, heading south on Paulina 14. The path will veer northeast up to the Lake 35. Turn right, heading west on Sunnyside 15. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................