Bulletin of Tibetology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nation Honours Sikkim's

Jan 28-03 Feb, 2003; NOW! 1 GAMMON GANGTOK, WEDNESDAY, Jan 28-03 Feb, 2004 SECURITY STAFFERS ACCUSED OF “BEATING UP” LOCAL DRIVER DETAILS ON pg 6 NOWSIKKIM MATTERS VOL 2 NO 29 ! Rs. 5 NATION HONOURS HANGING WeUP curse the telecom depart- SIKKIM’S ment often. But the next time we BSNL’S SIKKIM EXPERIENCE: start to do so, maybe we should stop and think. Given its Sikkim SON Experience, its a miracle that we still have a telecom network SISTER COLLECTS Rs. 11 crores in unpaid phone bills, Rs. 9 here. Any other organisation SANJOG’S ASHOK would have hung up its boots CHAKRA crores lost every year to theft of equipment long back. TURN TO pg 3 FOR DETAILS DETAILS ON pg 24 Panda rescue up north DETAILS ON pg 5 TOONG- NAGA WILL NOT GO THE DIKCHU WAY TURN TO pg 7 FOR DETAILS CMYK 2; NOW! ; Jan 28-03 Feb, 2004 GANGTOK JAN 28-03 FEB, 2004 ED-SPACE Trial & Error NOW! The poor and ignorant are the best guinea pigs. India hest of pharmaceutical companies on human beings SIKKIM MATTERS and some countries in Africa and Latin America have before the drugs have gone through the proper pro- often provided unscrupulous pharmaceutical com- tocols of animals testing, should have been free to Problems With Free Speech panies with human material upon whom to test un- continue with their activities with some other drug. tried drugs. The freedom to speak, like any other freedom ends where This in itself indicates the low priority given to ille- someone else’s space starts getting encroached. -

The Politics of Masculinity in Tony Gould's Imperial Warriors

TheThe Politics Outlook: of Masculinity Journal in Tony of Gould’s English Imperial Studies Warriors ISSN: 2565-4748 (Print); ISSN: 2773-8124 (Online) Published by Department of English, Prithvi Narayan Campus Tribhuvan University, Pokhara, Nepal [A Peer-Reviewed, Open Access Journal; Indexed in NepJOL] http://ejournals.pncampus.edu.np/ejournals/outlook/ THEORETICAL/CRITICAL ESSAY ARTICLE The Politics of Masculinity in Tony Gould’s Imperial Warriors: Britain and the Gurkhas Ram Prasad Rai Department of English, Ratna Rajyalaxmi Campus, Kathmandu, Nepal Article History:1Submitted 2 June 2021; Reviewed 20 June 2021; Revised 4 July 2021 Corresponding Author: Ram Prasad Rai, Email: [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/ojes.v12i1.38749 Abstract The main concern of this paper is to study on masculinity and more importantly the hyper masculinity of the Gorkhas in Imperial Warriors: Britain and the Gurkhas by Tony Gould. The writer describes the courage with discipline and dedication, the Gorkhas had while fighting for Nepal, their homeland during the Anglo-Nepal War (1814-1816) and for Britain in the First and Second World Wars, following the other wars and confrontations in many parts of the world. Despite a lot of hardships and pain in wars, they never showed their back to the enemies, but kept Britain’s imperial image always high with victories. They received Victoria Crosses along with other bravery medals. As a masculinity, the hegemonic masculinity is obviously present in the book since the high ranked British Officers are in the position to lead the Gorkha soldiers. However, the masculinity here is associated with the extreme level of bravery and that is the hyper- masculinity of the Gorkhas. -

The Unexpected Afterlives of Himalayan Collections 243

The Unexpected Afterlives of Himalayan Collections 243 that materials collected in ethically dubious circumstances can—some- seven times—have surprisingly rich and engaging rebirths. And as such, this contribution is as much about material heritage as it is about heritage material. Horst and Miller propose that the digital “itself intensifies the The Unexpected Afterlives dialectical nature of culture” (2012: 3). We might consider whether con- of Himalayan Collections: From temporary processes of repatriation and digital return can in some man- ner compensate for the defects of the original context of collection. Data Cemetery to Web Portal This contribution focuses on two collecting expeditions, or more cor- rectly collectors, since their expeditions were ongoing and cumulative. Mark Turin Frederick Williamson and Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf were both active from the 1930s on, the former in his capacity as a colonial servant of the British Empire, the latter as a prolific ethnographer. Both Wil- liamson and von Fürer-Haimendorf lived and worked through the last great classificatory era of colonial exploration and expansion, and both were skilled users of visual recording media to document the peoples Reassembly Requires Assembly and cultures they encountered. Williamson and von Fürer-Haimendorf were also part of what Erik Every time we use the word “real” analytically, Mueggler (this volume) has referred to (in relation to Joseph Rock), as as opposed to colloquially, we undermine the the “wandering generation,” men who left home to explore other ways project of digital anthropology, fetishizing pre- of life abroad. Unlike Rock, however, neither Williamson nor von Fürer- digital culture as a site of retained authenticity. -

The Gallantry Gazette JULY 2018 the Magazine for Victoria Cross Collectors Issue 19

The Gallantry Gazette JULY 2018 The magazine for Victoria Cross collectors Issue 19 MAJOR GENERAL HENRY ROBERT BOWREMAN FOOTE VC, CB, DSO (1904-1993) The London Gazette War Office, 18th May, 1944. attempt to encircle two of our Divisions. The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the award On 13th June, when ordered to delay the enemy tanks so that the Guards of the VICTORIA CROSS to:- Brigade could be withdrawn from the Knightsbridge escarpment and when Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) Henry Robert Bowreman Foote, the first wave of our tanks had been destroyed, Lieutenant-Colonel Foote D.S.O. (31938), Royal Tank Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps (Edgbaston, re-organised the remaining tanks, going on foot from one tank to another to Birmingham). encourage the crews under intense artillery and anti-tank fire. For outstanding gallantry during the period 27th May to 15th June 1942. As it was of vital importance that his Battalion should not give ground, Lieutenant-Colonel Foote placed his tank, which he had then entered, in front of On the 6th June, Lieutenant-Colonel Foote led his Battalion, which had been the others so that he could be plainly visible in the turret as an encouragement subjected to very heavy artillery fire, in pursuit of a superior force of the enemy. to the other crews, in spite of the tank being badly damaged by shell fire and While changing to another tank after his own had been knocked out, Lieutenant- all its guns rendered useless. By his magnificent example the corridor was kept Colonel Foote was wounded in the neck. -

King Arthur Comes to Tibet: Frank Ludlow and the English School in Gyantse, 1923-26 1

BULLETIN OF TIBETOLOGY 49 KING ARTHUR COMES TO TIBET: FRANK LUDLOW AND 1 THE ENGLISH SCHOOL IN GYANTSE, 1923-26 MICHAEL RANK With the spread of the British Empire, the British educational system also spread across the world, and this is the story of how, in the early 1920s, it reached as far as Tibet. The English School at Gyantse in southern Tibet had its origins in the aftermath of the 1903-04 Younghusband Expedition which enabled Britain to gain a foothold in the “Roof of the World”. Britain consolidated its advance in the Simla Convention of 1913-14. At about this time it was decided to send four young Tibetans, aged between 11 and 17, to Rugby school in England to learn English and the technical skills necessary to help their country to modernise. At the Simla Convention, the idea of setting up a British-run school in Tibet also came up. Sir Charles Bell, doyen of British policy in Tibet, noted that it was the Tibetan Plenipotentiary who broached the subject: “Something of the kind seems indispensable to enable the Tibetan Government to meet the pressure of Western civilization. And they themselves are keen on it. Without such a general school education Tibetans cannot be trained to develop their country in accordance with their own wishes.” 2 Britain was anxious that it was not viewed as imposing its values on Tibet, and another Government of India official stressed that it should be “made clear that the school is being established by the Tibetans on their own initiative and will be entirely their own affair— 1 I am grateful to Dr Anna Balikci-Denjongpa, editor of the Bulletin of Tibetology , for her support, and to Dr Mark Turin for suggesting that I submit this article to the journal. -

Holy Cross Fax: Worcester, MA 01610-2395 UNITED STATES

NEH Application Cover Sheet Summer Seminars and Institutes PROJECT DIRECTOR Mr. Todd Thornton Lewis E-mail:[email protected] Professor of World Religions Phone(W): 508-793-3436 Box 139-A 425 Smith Hall Phone(H): College of the Holy Cross Fax: Worcester, MA 01610-2395 UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: Religion: Nonwestern Religion INSTITUTION College of the Holy Cross Worcester, MA UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Literatures, Religions, and Arts of the Himalayan Region Grant Period: From 10/2014 to 12/2015 Field of Project: Religion: Nonwestern Religion Description of Project: The Institute will be centered on the Himalayan region (Nepal, Kashmir, Tibet) and focus on the religions and cultures there that have been especially important in Asian history. Basic Hinduism and Buddhism will be reviewed and explored as found in the region, as will shamanism, the impact of Christianity and Islam. Major cultural expressions in art history, music, and literature will be featured, especially those showing important connections between South Asian and Chinese civilizations. Emerging literatures from Tibet and Nepal will be covered by noted authors. This inter-disciplinary Institute will end with a survey of the modern ecological and political problems facing the peoples of the region. Institute workshops will survey K-12 classroom resources; all teachers will develop their own curriculum plans and learn web page design. These resources, along with scholar presentations, will be published on the web and made available for teachers worldwide. BUDGET Outright Request $199,380.00 Cost Sharing Matching Request Total Budget $199,380.00 Total NEH $199,380.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

From Data Cemetery to Web Portal Mark Turin

The unexpected afterlives of Himalayan collections: From data cemetery to web portal Mark Turin To cite this version: Mark Turin. The unexpected afterlives of Himalayan collections: From data cemetery to web por- tal. JOSHUA A. BELL; ERIN L. HASINOFF. The anthropology of expeditions: Travel, visualities, afterlives, University of Chicago Press, pp.242-268, 2015, 978-1941792001. halshs-03083357 HAL Id: halshs-03083357 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03083357 Submitted on 27 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Unexpected Afterlives of Himalayan Collections 243 that materials collected in ethically dubious circumstances can—some- seven times—have surprisingly rich and engaging rebirths. And as such, this contribution is as much about material heritage as it is about heritage material. Horst and Miller propose that the digital “itself intensifies the The Unexpected Afterlives dialectical nature of culture” (2012: 3). We might consider whether con- of Himalayan Collections: From temporary processes of repatriation and digital return can in some man- ner compensate for the defects of the original context of collection. Data Cemetery to Web Portal This contribution focuses on two collecting expeditions, or more cor- rectly collectors, since their expeditions were ongoing and cumulative. -

Nepali Times

#55 10 - 16 August 2001 20 pages Rs 20 10-1110-1110-11 191919 NEPNEPNEPALIALIALI VICTORIA CROSSES HARE KRISHNA EXCLUSIVE BINOD○○○○○○○○○○○○ BHATTARAI ○○○○ he method is psychological warfare: intimidation, threats T and panic. The result: the Maoists’ ban on alcohol sales and consumption nationwide from 18 HIGH AND DRY August is a move that will cost the Despite the truce, the Maoists are going for the state’s economic already cash-strapped government Royal mess Rs 10 billion a year in revenue alone. jugular. More than 500,000 people directly Development Programme (ISDP) not out to wreck the to be Maoists. Extortion and Royal Nepal Airlines’ nosedive scrapped. And last but not least, economy, and deny that intimidation has gone into high gear has come to this: cancelling its and indirectly dependent on the trunk routes at the beginning of brewery and distillery industries will they wanted all “unequal treaties” they are trying to Taliban- since the truce was announced on the autumn tourist season. be affected. Some 50,000 retailers (presumably with India) abrogated. ise Nepal. Maoist leader 23 July, and the Maoists appear to European routes, Singapore and and wholesalers across Nepal will The Maoist paper, Janadesh, Baburam Bhattarai told us in be on a spree to fill up their coffers. Dubai were haemorrhaging cash be hit. quoted Deuba as telling the women: an interview (#51) last month: Almost every big business we and have been stopped. A The underground Maoists have “Your demands are legitimate, I will “Please do not mistake us for privately polled were already victims tourism slump after the royal pushed their anti-alcohol campaign try to fulfil them within the religious fanatics like the of Maoist blackmail and admitted massacre did take its toll, but the through the above-ground All constitutional framework.” The Taliban…we have no agenda for that they have been paying them airline suffers from chronic Nepal Women’s Organisation prime minister’s office has not puritanical fads like the alcohol ban. -

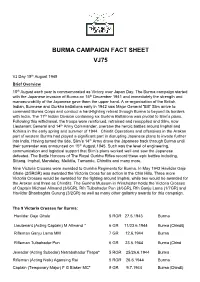

Burma Campaign Fact Sheet Vj75

BURMA CAMPAIGN FACT SHEET VJ75 VJ Day 15th August 1945 Brief Overview 15th August each year is commemorated as Victory over Japan Day. The Burma campaign started with the Japanese invasion of Burma on 15th December 1941 and immediately the strength and manoeuvrability of the Japanese gave them the upper hand. A re-organisation of the British, Indian, Burmese and Gurkha battalions early in 1942 saw Major General “Bill” Slim arrive to command Burma Corps and conduct a hard-fighting retreat through Burma to beyond its borders with India. The 17th Indian Division containing six Gurkha Battalions was pivotal to Slim’s plans. Following this withdrawal, the troops were reinforced, retrained and resupplied and Slim, now Lieutenant General and 14th Army Commander, oversaw the heroic battles around Imphal and Kohima in the early spring and summer of 1944. Chindit Operations and offensives in the Arakan part of western Burma had played a significant part in disrupting Japanese plans to invade further into India. Having turned the tide, Slim’s 14th Army drove the Japanese back through Burma until their surrender was announced on 15th August 1945. Such was the level of engineering, communication and logistical support that Slim’s plans worked well and saw the Japanese defeated. The Battle Honours of The Royal Gurkha Rifles record these epic battles including, Sittang. Imphal, Mandalay, Meiktila, Tamandu, Chindits and many more. Nine Victoria Crosses were awarded to Gurkha Regiments for Burma. In May 1943 Havildar Gaje Ghale (2/5RGR) was awarded the Victoria Cross for an action in the Chin Hills. Three more Victoria Crosses would be awarded for the fighting around Imphal, while two would be awarded for the Arakan and three as Chindits. -

Object Lessons in Tibetan: the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Charles Bell, and Connoisseurial Networks in Darjeeling and Kalimpong, 1910–12

PART III Things that Connect: Economies and Material Culture Emma Martin Object Lessons in Tibetan: The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Charles Bell, and Connoisseurial Networks in Darjeeling and Kalimpong, 1910–12 Abstract On 18 June 1912, Charles Bell, Political Officer of Sikkim, paid his final visit to the thirteenth Dalai Lama at Bhutan House in Kalimpong. The significant gifts presented that day were the culmination of a series of object exchanges between the two men during the lama’s exile in British India. These gifting moments were not only characterized by the mobility of the objects in question, but by the connoisseurial and empirical knowl- edge regularly offered with them. Using the concept of “object lessons,” this paper traces out how Bell was taught things with Tibetan objects. Fur- thermore, these exchanges are not only placed within the context of the Dalai Lama’s exile in Darjeeling and Kalimpong between 1910 and 1912, but they highlight the potential to make alternate readings of histories and encounters if one closely follows things. 177 EMMA MARTIN New arrivals A large procession of the faithful met the Tibetan pope some distance from the city and escorted him with grand ceremony. They carried banners, incense burners, and mul- ti-colored flags […]. The Dalai Lama was in a magnificent yellow sedan chair, with richly caparisoned bearers […]. The Dalai Lama and his suite were installed in Druid Hotel […]. His bed chamber is draped throughout with yellow silk. There is an altar in the corner of the room and incense lamps burn incessantly before images of Buddha, which were especially brought here from Gartok by the Maharaja of Sikkim (“The Lama in India: Crowds Greet Him” 1910). -

The Gurkha Museum

THE BRITAIN-NEPAL SOCIETY J o u r n a l Number 36 2012 A LEGACY OF LOYALTY That is why we are asking those In just the last four years the If you do write or amend your who do remember, to consider monthly ‘welfare pension’ we Will to make a provision for the making a provision now for the pay to some 10,400 Gurkha Trust then do please let us know. time when funding and support ex-servicemen and widows has We hope it will be many years for Gurkha welfare will be much risen from 2,500 NCR to 3,800 before we see the benefit of your harder to come by. You can do NCR to try and keep pace legacy, but knowing that a this by a legacy or bequest to the with inflation in Nepal. Welfare number of our supporters have Gurkha Welfare Trust in your Will. pensions alone cost the Trust £4.4 remembered the Trust in their million last year. Who knows what Wills helps so much in our This will help to ensure the the welfare pension will need to be forward planning. Thank you. long-term future of our work. in 10 or 20 years time. PLEASE WRITE TO: The Gurkha Welfare Trust, PO Box 2170, 22 Queen Street, Salisbury SP2 2EX, telephone us on 01722 323955 or e-mail [email protected] Registered charity No. 1103669 THE BRITAIN-NEPAL SOCIETY Journal Number 36 2012 CONTENTS 2 Editorial 3 The Society’s News 7 A Secret Expedition to Dolpo 20 The Remains of the Kosi Project Railway: an Obscure Grice 26 Three Virtues 34 The Digital Himalaya Project 41 Victoria Crosses Awarded to Britain’s Indian Army Gurkhas 1911 – 1947 43 Gurkha Settlement in UK – An Update 45 Women Without Roofs 48 From the Editor’s In-Tray 51 Book Reviews 53 Obituaries 58 Useful addresses 59 Notes on the Britain – Nepal Society 60 Officers and Committee of the Society 1 EDITORIAL Firstly I must apologise for the late Royal Engineers used to clear a track publication of the 2012 edition of the through that area so that we could drive our journal which has been the result of Landrovers from the cantonment to the personal family circumstances. -

The Gurkhas: Special Force Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE GURKHAS: SPECIAL FORCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chris Bellamy | 464 pages | 13 Oct 2011 | Hodder & Stoughton General Division | 9781848543447 | English | London, United Kingdom The Gurkhas: Special Force PDF Book Gurkhas carrying out training in house-to-house combat whist on exercise in the US. The traditional Gurkha no. The selection process has been described as one of the toughest in the world and is fiercely contested. Between and , the Gurkha regiments were renumbered from the 1st to the 10th and re-designated as the Gurkha Rifles. His fingers were blown off and his face, body, and right arm and leg were badly wounded. The Gurkha trooper's no. During World War I — more than , Gurkhas served in the British Army, suffering approximately 20, casualties and receiving almost 2, gallantry awards. Gautama Buddha Maya mother of Buddha. At that time, their presence as a neutral force was important because local police officers were often perceived to be or were even expected to be biased towards their own ethnic groups when handling race-related issues, further fueling discontent and violence. The Gurkhas engaged in brief skirmishes with Indonesian forces around the main airport. A spokesperson for the Communist Party of Nepal Maoist , which was expected to play a major role in the new secular republic, stated that recruitment as mercenaries was degrading to the Nepalese people and would be banned. Books Video icon An illustration of two cells of a film strip. These words of wisdom come from perhaps the greatest British general of the second world war, Bill Slim. Main article: Gorkha regiments India.