Attention, Rehearsal in Progress! People Are Pigs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Silence of Lorna

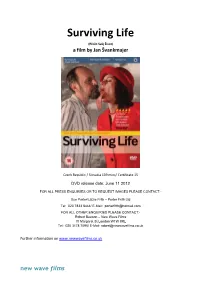

Surviving Life (Přežit Svůj Život) a film by Jan Švankmajer Czech Republic / Slovakia 109 mins/ Certificate 15 DVD release date: June 11 2012 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES OR TO REQUEST IMAGES PLEASE CONTACT:- Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/ E-Mail: [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT:- Robert Beeson – New Wave Films 10 Margaret St London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095/ E-Mail: [email protected] Further information on www.newwavefilms.co.uk new wave films Surviving Life Director Jan Švankmajer Script Jan Švankmajer Producer Jaromír Kallista Co‐Producers Juraj Galvánek, Petr Komrzý, Vít Komrzý, Jaroslav Kučera Associate Producers Keith Griffiths and Simon Field Music Alexandr Glazunov and Jan Kalinov Cinematography Jan Růžička and Juraj Galvánek Editor Marie Zemanová Sound Ivo Špalj Animation Martin Kublák, Eva Jakoubková, Jaroslav Mrázek Production Design Jan Švankmajer Costume Design Veronika Hrubá Production Athanor / C‐GA Film CZECH REPUBLIC/SLOVAKIA 2010 ‐ 109 MINUTES ‐ In Czech with English subtitles CAST Eugene , Milan Václav Helšus Eugenia Klára Issová Milada Zuzana Kronerová Super‐ego Emília Došeková Dr. Holubová Daniela Bakerová Colleague Marcel Němec Antiquarian Jan Počepický Prostitute Jana Oľhová Janitor Pavel Nový Boss Karel Brožek Fikejz Miroslav Vrba SYNOPSIS Eugene (Václav Helšus) leads a double life ‐ one real, the other in his dreams. In real life he has a wife called Milada (Zuzana Kronerová); in his dreams he has a young girlfriend called Eugenia (Klára Issová). Sensing that these dreams have some deeper meaning, he goes to see a psychoanalyst, Dr. Holubova, who interprets them for him, with the help of some argumentative psychoanalytical griping from the animated heads of Freud and Jung. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Artxsr, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* NOTE TO USERS Page(s) missing in number only; text follows. Page(s) were microfilmed as received. 131,172 This reproduction is the best copy available UMI FRANK WEDEKIND’S FANTASY WORLD: A THEATER OF SEXUALITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Bv Stephanie E. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Horror of Philosophy

978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page i In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page ii 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iii In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] Eugene Thacker Winchester, UK Washington, USA 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iv First published by Zero Books, 2011 Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK [email protected] www.o-books.com For distributor details and how to order please visit the ‘Ordering’ section on our website. Text copyright: Eugene Thacker 2010 ISBN: 978 1 84694 676 9 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers. The rights of Eugene Thacker as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design: Stuart Davies Printed in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe Printed in the USA by Offset Paperback Mfrs, Inc We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution. -

Page 1 of 3 Moma | Press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare

MoMA | press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare and Original Film Posters at ... Page 1 of 3 GALLERY EXHIBITION OF RARE AND ORIGINAL FILM POSTERS AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART SPOTLIGHTS LEGENDARY GERMAN MOVIE STUDIO Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 September 17, 1998-January 5, 1999 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby Exhibition Accompanied by Series of Eight Films from Golden Age of German Cinema From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics September 17-29, 1998 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Fifty posters for films produced or distributed by Ufa, Germany's legendary movie studio, will be on display in The Museum of Modern Art's Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby starting September 17, 1998. Running through January 5, 1999, Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 will feature rare and original works, many exhibited for the first time in the United States, created to promote films from Germany's golden age of moviemaking. In conjunction with the opening of the gallery exhibition, the Museum will also present From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics, an eight-film series that includes some of the studio's more celebrated productions, September 17-29, 1998. Ufa (Universumfilm Aktien Gesellschaft), a consortium of film companies, was established in the waning days of World War I by order of the German High Command, but was privatized with the postwar establishment of the Weimar republic in 1918. Pursuing a program of aggressive expansion in Germany and throughout Europe, Ufa quickly became one of the greatest film companies in the world, with a large and spectacularly equipped studio in Babelsberg, just outside Berlin, and with foreign sales that globalized the market for German film. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Like a Faint Echo Emanating from the Netherworld, the Theme of Temptation Is Sung by a Large Choir of Bass Voices As a Representation of Mephistopheles

Measures 1-11: Mephistopheles' theme: Like a faint echo emanating from the netherworld, the theme of temptation is sung by a large choir of bass voices as a representation of Mephistopheles. Mephistopheles promises Faust both joy and love in exchange for accepting the pact he's proposing. Measures 12-19: Faust's theme: Faust, a highly-educated scientist, is a lonely and bitter man who feels spurned by years devoted entirely to the pursuit of knowledge, while not providing him with any personal satisfaction. He has never tried to seduce the woman whom he has always loved from afar. In considering this situation, Faust laments. Measures 20-29: Reintroduction of the Mephistopheles theme (dialogue between Mephistopheles and Faust) In sensing Faust's vulnerability, Mephistopheles resumes his theme of temptation with greater force and conviction. Mephistopheles' words and promises resonate in Faust's subconscious. Measures 30-48: Reintroduction of Faust's theme, followed by the development of Mephistopheles' theme While continuing to lament his miserable situation, Faust is extremely tempted by Mephistopheles' entreaties. He considers teaming up with the Devil as a way of recovering from his dire situation and finally seducing the woman he associates with true Love. Faust winds up succumbing to temptation and enters into a pact with Mephistopheles (transition measure 36). At this point, Faust recites on his own Mephistopheles' theme, which then gets treated with a crescendo buildup until hitting higher notes. Faust feels "reborn". Measures 49-59: Finale Faust's theme is altered during a finale involving all instruments in the ensemble as well as the choir. -

A Film by Bohdan Sláma

ICE MOTHER A FILM BY BOHDAN SLÁMA 67-year old Hana is the good soul of her family. Every One day, while Hana is looking for Ivánek who sneaked week her sons come over with their wives and children for out, she finds a man, Broňa, floating at the riverside, unable to their family dinner. It is a family tradition not to be changed. move. She jumps in and helps him to get out of the icy water. Selfless, Hana takes care of the little Ivánek, who is not really Hana gets to know his elderly friends and suddenly she is cherishing his grandma’s help. She also supports her other included in a new social circle. Even little Ivánek is interested son with money everytime he asks for it – and he asks a lot. A in the funny quirky group of ice swimmers. warmhearted yet modest person, Hana continues to live alone in the old family house without changing a thing ever since Light-hearted Broňa, who lives in an old camper bus near her husband died a few years ago. She might need a helping the river, inspires Hana’s lust for life. They become lovers, hand but both her sons are too busy and too selfish to see it. but when she introduces him to her sons, the whole family is shocked. In a series of events and dark secrets, Hana has to stand up and start changing her life. Born in 1967 in Opava, Czech Republic, Bohdan Sláma studied film directing at Prague Film School FAMU. -

In Goethe's Faust, Unlike the Earlier Versions of the Story, the Faithless

1 In G oethe’s Faust, unlike the earlier versions of the story, the faithless sinner that is Faust receives grace and goes to Heaven, rather than being thrown to the fires of Hell. Faust’s redemption is contrary to every other redemption in every other story we have read up till now. Faust wasn’t asking forgiveness from God, unlike his beloved Margaret, and so many others before him. Faust doesn’t seem even to believe in the all mighty, even when directly talking to the Devil himself. Yet, in the end, Mephisto’s plot is foiled, Faust’s soul is not cast into the inferno, but raised to paradise. Goethe has Faust receive a secular salvation, through Faust’s actions rather than through his belief. Goethe shows both the importance of action versus words, and Faust’s familiarity with the Bible, with Faust’s translation of Logos, “It says: ‘In the beginning was the W ord… I write: In the beginning was the Act.” (G oethe's Faust, line 1224, 1237) Here, Faust demonstrates a clear understanding of a theological problem, the importance of a single word within the Bible. Having Logos translated as “the Word” has many more different implications than if it means “the Act”. The Act would imply the creation of everything was a direct application of Gods will. He did not need to say for something happen, God did something to put the universe in motion by action alone. Goethe includes this translation of Logos, as the Act instead of the Word, for several reasons. -

To Obtain His Soul’: Demonic Desire for the Soul in Marlowe and Others

Early Theatre 5.2(2002) john d. cox ‘To obtain his soul’: Demonic Desire for the Soul in Marlowe and Others ‘O, what will I not do to obtain his soul?’ exclaims Mephistopheles in Dr Faustus, at a moment of fearful doubt on Faustus’s part.1 The exclamation is a rare revelation of the devil’s purpose in this play. For the most part, Mephistopheles appears to be a courteous servant to a gentleman scholar: suave and anxious to please. His exclamation of desire for Faustus’s soul, however, betrays an unexpressed craving to dominate Faustus completely and forever. Mephistopheles has demanded that Faustus sign over his soul to the devil, but in the midst of signing Faustus has begun to waver, and the blood in the wound that he made to sign his name has ceased to flow. Surely this must be a providential warning against apostasy! Then Mephistopheles fetches a chafer of coals: ‘Here’s fire. Come, Faustus, set it on’ (2.1.70); the blood ‘begins to clear again’ (71); and Faustus signs. This is the moment at which Mephistopheles exclaims, in obvious self-congratulation, about his longing for Faustus’s soul. The exclamation seems to imply Mephistopheles’ glee at successful misdi- rection. Making the blood flow by warming the body reduces the problem of congealing blood to mere physiology, erasing Faustus’s fear of peril to his soul. Mephistopheles thus prevents Faustus from going back on his determination to serve the devil, so the demonic servant exults at having fooled Faustus into submission. This inference is confirmed when Mephistopheles uses the same technique immediately afterwards. -

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes K-19 : the widowmaker 45205 Kaajal 36701 Family/Musical Ka-annanā ʻishrūn mustaḥīl = Like 20 impossibles 41819 Ara Kaante 36702 Crime Hin Kabhi kabhie 33803 Drama/Musical Hin Kabhi khushi kabhie gham-- 36203 Drama/Musical Hin Kabot Thāo Sīsudāčhan = The king maker 43141 Kabul transit 47824 Documentary Kabuliwala 35724 Drama/Musical Hin Kadının adı yok 34302 Turk/VCD Kadosh =The sacred 30209 Heb Kaenmaŭl = Seaside village 37973 Kor Kagemusha = Shadow warrior 40289 Drama Jpn Kagerōza 42414 Fantasy Jpn Kaidan nobori ryu = Blind woman's curse 46186 Thriller Jpn Kaiju big battel 36973 Kairo = Pulse 42539 Horror Jpn Kaitei gunkan = Atragon 42425 Adventure Jpn Kākka... kākka... 37057 Tamil Kakushi ken oni no tsume = The hidden blade 43744 Romance Jpn Kakushi toride no san akunin = Hidden fortress 33161 Adventure Jpn Kal aaj aur kal 39597 Romance/Musical Hin Kal ho naa ho 41312, 42386 Romance Hin Kalyug 36119 Drama Hin Kama Sutra 45480 Kamata koshin-kyoku = Fall guy 39766 Comedy Jpn Kān Klūai 45239 Kantana Animation Thai Kanak Attack 41817 Drama Region 2 Kanal = Canal 36907, 40541 Pol Kandahar : Safar e Ghandehar 35473 Farsi Kangwŏn-do ŭi him = The power of Kangwon province 38158 Kor Kannathil muthamittal = Peck on the cheek 45098 Tamil Kansas City 46053 Kansas City confidential 36761 Kanto mushuku = Kanto warrior 36879 Crime Jpn Kanzo sensei = Dr. Akagi 35201 Comedy Jpn Kao = Face 41449 Drama Jpn Kaos 47213 Ita Kaosu = Chaos 36900 Mystery Jpn Karakkaze yarô = Afraid to die 45336 Crime Jpn Karakter = Character -

Jan Švankmajer - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 2/18/08 6:16 PM

Jan Švankmajer - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2/18/08 6:16 PM Jan Švankmajer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jan Švankmajer (born 4 September 1934 in Prague) is a Jan Švankmajer Czech surrealist artist. His work spans several media. He is known for his surreal animations and features, which have greatly influenced other artists such as Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, The Brothers Quay and many others. Švankmajer has gained a reputation over several decades for his distinctive use of stop-motion technique, and his ability to make surreal, nightmarish and yet somehow funny pictures. He is still making films in Prague at the time of Still from Dimensions of Dialogue, 1982 writing. Born 4 September 1934 Prague, Czechoslovakia Švankmajer's trademarks include very exaggerated sounds, often creating a very strange effect in all eating scenes. He Occupation Animator often uses very sped-up sequences when people walk and Spouse(s) Eva Švankmajerová interact. His movies often involve inanimate objects coming alive and being brought to life through stop-motion. Food is a favourite subject and medium. Stop-motion features in most of his work, though his feature films also include live action to varying degrees. A lot of his movies, like the short film Down to the Cellar, are made from a child's perspective, while at the same time often having a truly disturbing and even aggressive nature. In 1972 the communist authorities banned him from making films, and many of his later films were banned. He was almost unknown in the West until the early 1980s. Today he is one of the most celebrated animators in the world.