A Queer Teen's Guide to Syndicated Sexualities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

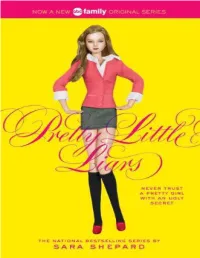

Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars

Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead. Benjamin Franklin How It All Started Imagine it’s a couple of years ago, the summer between seventh and eighth grade. You’re tan from lying out next to your rock-lined pool, you’ve got on your new Juicy sweats (remember when everybody wore those?), and your mind’s on your crush, the boy who goes to that other prep school whose name we won’t mention and who folds jeans at Abercrombie in the mall. You’re eating your Cocoa Krispies just how you like ’em – doused in skim milk – and you see this girl’s face on the side of the milk carton. MISSING. She’s cute – probably cuter than you – and has a feisty look in her eyes. You think, Hmm, maybe she likes soggy Cocoa Krispies too. And you bet she’d think Abercrombie boy was a hottie as well. You wonder how someone so . well, so much like you went missing. You thought only girls who entered beauty pageants ended up on the sides of milk cartons. Well, think again. Aria Montgomery burrowed her face in her best friend Alison DiLaurentis’s lawn. ‘Delicious,’ she murmured. ‘Are you smelling the grass?’ Emily Fields called from behind her, pushing the door of her mom’s Volvo wagon closed with her long, freckly arm. ‘It smells good.’ Aria brushed away her pink-striped hair and breathed in the warm early-evening air. ‘Like summer.’ Emily waved ’bye to her mom and pulled up the blah jeans that were hanging on her skinny hips. -

Hrc-Coming-Out-Resource-Guide.Pdf

G T Being brave doesn’t mean that you’re not scared. It means that if you are scared, you do the thing you’re afraid of anyway. Coming out and living openly as a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or supportive straight person is an act of bravery and authenticity. Whether it’s for the first time ever, or for the first time today, coming out may be the most important thing you will do all day. Talk about it. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Welcome 3 Being Open with Yourself 4 Deciding to Tell Others 6 Making a Coming Out Plan 8 Having the Conversations 10 The Coming Out Continuum 12 Telling Family Members 14 Living Openly on Your Terms 15 Ten Things Every American Ought to Know 16 Reference: Glossary of Terms 18 Reference: Myths & Facts About LGBT People 19 Reference: Additional Resources 21 A Message From HRC President Joe Solmonese There is no one right or wrong way to come out. It’s a lifelong process of being ever more open and true with yourself and others — done in your own way and in your own time. WELCOME esbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Americans Lare sons and daughters, doctors and lawyers, teachers and construction workers. We serve in Congress, protect our country on the front lines and contribute to the well-being of the nation at every level. In all that diversity, we have one thing in common: We each make deeply personal decisions to be open about who we are with ourselves and others — even when it isn’t easy. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

Prettylittleliars: How Hashtags Drive the Social TV Phenomenon

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses Summer 6-2013 #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon Melanie Brozek Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Brozek, Melanie, "#PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon" (2013). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 93. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon By Melanie Brozek Prepared for Dr. Esch English Department Salve Regina University May 10, 2013 Brozek 2 #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon ABSTRACT: Twitter is used by many TV shows to promote discussion and encourage viewer loyalty. Most successfully, ABC Family uses Twitter to promote the teen drama Pretty Little Liars through the use of hashtags and celebrity interactions. This study analyzes Pretty Little Liars’ use of hashtags created by the network and by actors from the show. It examines how the Pretty Little Liars’ official accounts engage fans about their opinions on the show and encourage further discussion. Fans use the network- generated hashtags within their tweets to react to particular scenes and to hopefully be noticed by managers of official show accounts. -

Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls' Inclusion Of

WATCHING TELEVISION WITH FRIENDS: TWEEN GIRLS’ INCLUSION OF TELEVISUAL MATERIAL IN FRIENDSHIP by CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Childhood Studies written under the direction of Daniel Thomas Cook and approved by ______________________________ Daniel T. Cook ______________________________ Anna Beresin ______________________________ Todd Wolfson Camden, New Jersey May 2016 ABSTRACT Watching Television with Friends: Tween Girls’ Inclusion of Televisual Material in Friendship By CYNTHIA MICHIELLE MAURER Dissertation Director: Daniel Thomas Cook This qualitative work examines the role of tween live-action television shows in the friendships of four tween girls, providing insight into the use of televisual material in peer interactions. Over the course of one year and with the use of a video camera, I recorded, observed, hung out and watched television with the girls in the informal setting of a friend’s house. I found that friendship informs and filters understandings and use of tween television in daily conversations with friends. Using Erving Goffman’s theory of facework as a starting point, I introduce a new theoretical framework called friendship work to locate, examine, and understand how friendship is enacted on a granular level. Friendship work considers how an individual positions herself for her own needs before acknowledging the needs of her friends, and is concerned with both emotive effort and social impact. Through group television viewings, participation in television themed games, and the creation of webisodes, the girls strengthen, maintain, and diminish previously established bonds. -

Deputy Registrars

Deputy Registrars December 2020 - November 2022 Channahon Township Minooka C.C.S.D. No. 201 305 W. Church St., Minooka 60447 Registrars: Phone: 815/467-6121 Lori K. Shanholtzer Email: [email protected] Village of Channahon 24555 S. Navajo Dr., Channahon 60410 Registrars: Phone: 815/467-6644 Leticia R. Anselme Email: [email protected] Jean Chudy Email: [email protected] Mary Jane Larson Email: [email protected] Stephanie Lee Mutz Email: [email protected] Crete Township Crete Public Library District 1177 N. Main St., Crete 60417 Registrars: Phone: 708/672-8017 Tiffany C. Amschl Email: [email protected] Christine LeVault Email: [email protected] Thursday, September 30, 2021 Page 1 of 20 Crete Township Crete Township Office 1367 Wood St., Crete 60417 Registrars: Phone: 708/672-8279 James Buiter Email: [email protected] Steven Hanus Email: [email protected] Village of Crete 524 Exchange St., Crete 60417 Registrars: Phone: 708/672-5431 Kimberly A. Adams Email: [email protected] Deborah S. Bachert Email: [email protected] Susan Peterson Email: [email protected] Christine S. Whitaker Email: [email protected] Village Woods 2681 S. Rte. 394, Crete 60417 Registrars: Phone: 708/672-6111 Elyssia E. Roozeboom Email: [email protected] Custer Township Custer Township Office 35332 Grant Ave, Custer Park 60481 Registrars: Phone: 815-530-7207 Christine Olson Email: [email protected] Thursday, September 30, 2021 Page 2 of 20 DuPage Township DuPage Township Office 241 Canterbury Ln., Bolingbrook 60440 Registrars: Phone: 630/759-1317 Amy Albright Email: [email protected] Barbara Parker Email: [email protected] Fountaindale Public Library 300 W. -

Tick-Tock, B**Ches”

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 7.01 “Tick-Tock, B**ches” In a desperate race to save one of their own, the girls must decide whether to hand over evidence of Charlotte's real murderer to "Uber A." WRITTEN BY: I. Marlene King DIRECTED BY: Ron Lagomarsino ORIGINAL BROADCAST: June 21, 2016 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Tyler Blackburn ... Caleb Rivers Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Andrea Parker ... Mary Drake Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal Sasha Pieterse ... Alison Rollins Keegan Allen ... Toby Cavanaugh Huw Collins ... Dr. Elliott Rollins Lulu Brud ... Sabrina Ray Fonseca ... Bartender P a g e | 1 1 00:00:08,509 --> 00:00:10,051 How could we let this happen? 2 00:00:11,512 --> 00:00:12,972 Oh, my God, poor Hanna. 3 00:00:13,012 --> 00:00:14,807 Try to remember that it's what she'd want. 4 00:00:16,684 --> 00:00:19,561 No, I don't know if I can live with this. 5 00:00:19,603 --> 00:00:21,522 I mean, how can we bury.. 6 00:00:23,064 --> 00:00:27,027 - There has to be another way. -

LGBT History

LGBT History Just like any other marginalized group that has had to fight for acceptance and equal rights, the LGBT community has a history of events that have impacted the community. This is a collection of some of the major happenings in the LGBT community during the 20th century through today. It is broken up into three sections: Pre-Stonewall, Stonewall, and Post-Stonewall. This is because the move toward equality shifted dramatically after the Stonewall Riots. Please note this is not a comprehensive list. Pre-Stonewall 1913 Alfred Redl, head of Austrian Intelligence, committed suicide after being identified as a Russian double agent and a homosexual. His widely-published arrest gave birth to the notion that homosexuals are security risks. 1919 Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexology in Berlin. One of the primary focuses of this institute was civil rights for women and gay people. 1933 On January 30, Adolf Hitler banned the gay press in Germany. In that same year, Magnus Herschfeld’s Institute for Sexology was raided and over 12,000 books, periodicals, works of art and other materials were burned. Many of these items were completely irreplaceable. 1934 Gay people were beginning to be rounded up from German-occupied countries and sent to concentration camps. Just as Jews were made to wear the Star of David on the prison uniforms, gay people were required to wear a pink triangle. WWII Becomes a time of “great awakening” for queer people in the United States. The homosocial environments created by the military and number of women working outside the home provide greater opportunity for people to explore their sexuality. -

Wanted: Dead Or Alive”

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 7.06 “Wanted: Dead or Alive” Hanna struggles with whether to tell the police the truth about Rollins. Emily challenges Jenna, who reveals part of her plot. WRITTEN BY: Lijah Barasz DIRECTED BY: Bethany Rooney ORIGINAL BROADCAST: August 2, 2016 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Tyler Blackburn ... Caleb Rivers Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Andrea Parker ... Mary Drake Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal (credit only) Sasha Pieterse ... Alison Rollins Vanessa Ray ... CeCe Drake / Charlotte DiLaurentis Huw Collins ... Dr. Elliott Rollins / Archer Dunhill Dre Davis ... Sara Harvey Nicholas Gonzalez ... Detective Marco Furey Tammin Sursok ... Jenna Marshall Dawn Brodey ... Maid P a g e | 1 1 00:00:07,925 --> 00:00:10,051 Aria, I called you last night 2 00:00:10,093 --> 00:00:12,220 after you went to Ezra's. 3 00:00:12,262 --> 00:00:15,015 Yeah. I'm sorry I didn't get back to you. 4 00:00:15,056 --> 00:00:16,183 Well, is everything okay? 5 00:00:16,224 --> 00:00:18,059 Did he find out about the Nicole call? 6 00:00:18,101 --> 00:00:19,979 No, he didn't. -

Interview with Sheetal Sheth | Afterellen.Com

Interview with Sheetal Sheth | AfterEllen.com Welcome to AfterEllen.com! Like 17k Follow @afterellen LOGIN | JOIN NOW! AFTERELLEN.COM TV MOVIES PEOPLE COLUMNS MUSIC VIDEO COMMUNITY LADY KNIGHTS IN SHINING ARMOR WEB Home » Interview with Sheetal Sheth Posted by Bridget McManus on March 31, 2011 Tweet Like 6 Actress Sheetal Sheth is no stranger to controversy. She made her debut in the film ABCD , playing a promiscuous young woman struggling with the ties of family and tradition. It garnered a lot of attention from press and audiences , both positive and negative. The Indian American beauty held her own against Albert Brooks in Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World, she fell in love with actress Lisa Ray in Shamim Sarif's beloved films The World Unseen and I Can't Think Straight. She also bested me during a pillow fight on my Logo show Brunch with Bridget. (I totally let her win!) Sheth is dealing with controversy once again with her latest film, Three Veils. The films follows RECENT COMMENTS three Middle Eastern women and who deal with abuse, rape and struggles with their sexuality. The script was originally boycotted but was saved thanks to the efforts of the film's director and I'm obsessed with all things producer. Posted by tophtheearthbender About: Why smart lesbians read (and write) fan fiction I spoke with Sheth about her powerful new role, where she lands on the Kinsey scale and why (61) she seems to be drawn to controversy. Try these three Hunter Posted by tophtheearthbender About: “The Real L Word” recap: Episode 301 – “Apples and Oranges” (21) Missy Higgins Posted by roni1133 About: New Music Wednesday: Missy Higgins, Icky Blossoms, Angel Haze and more (3) Yes they do. -

Enter Your Title Here in All Capital Letters

EXPLORING THE COMPOSITION AND FORMATION OF LESBIAN SOCIAL TIES by LAURA S. LOGAN B.A., University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2006 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2008 Approved by: Major Professor Dana M. Britton Copyright LAURA S. LOGAN 2008 Abstract The literature on friendship and social networks finds that individuals form social ties with people who are like them; this is termed “homophily.” Several researchers demonstrate that social networks and social ties are homophilous with regard to race and class, for example. However, few studies have explored the relationship of homophily to the social ties of lesbians, and fewer still have explicitly examined sexual orientation as a point of homophily. This study intends to help fill that gap by looking at homophily among lesbian social ties, as well as how urban and non-urban residency might shape homophily and lesbian social ties. I gathered data that would answer the following central research questions: Are lesbian social ties homophilous and if so around what common characteristics? What are lesbians’ experiences with community resources and how does this influence their social ties? How does population influence lesbian social ties? Data for this research come from 544 responses to an internet survey that asked lesbians about their social ties, their interests and activities and those of their friends, and the cities or towns in which they resided. Using the concepts of status and value homophily, I attempt to make visible some of the factors and forces that shape social ties for lesbians. -

Interpreting Popular Photographs on Afterellen.Com

MAKING OUT ON THE INTERNET: INTERPRETING POPULAR PHOTOGRAPHS ON AFTERELLEN.COM CAITLIN J. MCKINNEY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER'S OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE, JOINT PROGRAM WITH RYERSON UNIVERSITY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO SEPTEMBER 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-80628-9 Our file Notre r6f$rence ISBN: 978-0-494-80628-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.