PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Crisis: Towards a Sustainable Growth Model

After the crisis: towards a sustainable growth model Edited by Andrew Watt and Andreas Botsch, senior researchers, ETUI European Trade Union Institute © European Trade Union Institute, aisbl, 2010 All rights reserved ISBN: 978-2-87452-170-6 D/2010/10.574/06 Price: 20 euros Graphic Design: Coast Photo: ©Getty Printed in Belgium by Impresor Pauwels The ETUI is financially supported by the European Community. The European Community is not responsible for any use made of the information contained in this publication. www.etui.org Table of contents 5 45 75 Introduction Stefan Schulmeister Allan Larsson A general financial transac- Stress-testing Europe’s Part 1 tion tax: enhancing stability social systems Re-regulating and fiscal consolidation the financial sector 79 50 Friederike Maier 17 Andreas Botsch Re-cession or He-cession Sony Kapoor After the financial - gender dimensions of eco- Principles for financial market crisis — a trade nomic crisis and economic system reform union agenda policy 21 Part 2 84 Dean Baker Building a real economy Jill Rubery Recipe for reform: account- for equality, social justice Salvaging gender equality able regulators and a and good jobs for all policy smaller financial sector 57 88 25 Eileen Appelbaum Ewart Keep and Paul De Grauwe After the crisis: employment Ken Mayhew The future of banking relations for sustained Training and skills during recovery and growth and after the crisis – what 28 to do and what not to do Yiannis Kitromilides 61 Should banks be Ronald Schettkat 92 nationalised? Employment after the Mario Pianta crisis: New Deal for Europe Industrial and innovation 32 required policies in Europe Robert Kuttner Reforming finance 66 96 Sandrine Cazes and Wiemer Salverda 36 Sher Verick Inequality and the great Helene Schuberth Labour market policies in (wage) moderation Making finance serve times of crisis society 100 71 Thorsten Schulten 41 Bernard Gazier A European minimum wage Thomas I. -

To Read the Report

MAKING EUROPEAN CITIZENS: CHALLENGES TO SOLIDARITY AMONG EU MEMBER STATES Evaluator Conny Reuter Director of the Progressive Alliance & Former Secretary-General of the EU NGO network SOLIDAR Faculty Advisor Sabine Lang Director of Center for West European Studies Program Coordinators Addie Perkins Lexi Kinzer Editors Lexi Kinzer Addie Perkins Report Cover Erik Levi Stone Authors Madison Rose Keiran Lexi Kinzer Esmé Lafi Mahilet Mesfin Olivia Nicolas Juliet Rose Romano-Olsen Addie Perkins Evple Peng Tommy Shi Erik Levi Stone ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our deepest gratitude goes to Professor Sabine Lang, who was like our own personal library of all things European. You showed us a great deal of patience, gave us suggestions that we didn’t even know we needed, accelerated our learning and pushed us like baby birds to dive down towards the depths of the Europeans Union’s policies. Danke sehr! We would also like to thank the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies for making Task Force possible, and bad education impossible, for supporting students in their research endeavors and continuously challenging us to think critically about the world. To Kian Flynn, who helped us begin out research journey, thank you! We are also appreciative of our evaluator Conny Reuter for taking the time out of his busy schedule to not only evaluate our report but also discuss and debate with us about the realities and uncertainties behind EU solidarity and what it holds for the future of Europe. Finally, we are sincerely grateful to all the ten authors who contributed to this Task Force Report, who are most likely snoozing, right this moment, in solidarity. -

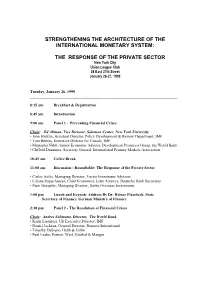

Strengthening the Architecture of the International Monetary System

STRENGTHENING THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM: THE RESPONSE OF THE PRIVATE SECTOR New York City Union League Club 38 East 37th Street January 26-27, 1999 Tuesday, January 26, 1999 ___________________________________________________________________________ 8:15 am Breakfast & Registration 8:45 am Introduction 9:00 am Panel 1 - Preventing Financial Crises Chair : Ed Altman, Vice Director, Salomon Center, New York University • John Hicklin, Assistant Director, Policy Development & Review Department, IMF • Tom Bernes, Executive Director for Canada, IMF • Mustapha Nabli, Senior Economic Adviser, Development Prospects Group, the World Bank • Clifford Dammers, Secretary General, International Primary Markets Association 10:45 am Coffee Break 11:00 am Discussion - Roundtable: The Response of the Private Sector • Carlos Asilis, Managing Director, Vector Investment Advisors • Liliana Rojas-Suarez, Chief Economist, Latin America, Deutsche Bank Securities • Peter Geraghty, Managing Director, Darby Overseas Investments 1:00 pm Lunch and Keynote Address By Dr. Heiner Flassbeck, State Secretary of Finance, German Ministry of Finance 2:30 pm Panel 2 - The Resolution of Financial Crises Chair: Andres Solimano, Director, The World Bank • Karin Lissakers, US Executive Director, IMF • Daniel Jackson, General Director, Nomura International • Timothy DeSieno, Hebb & Gitlin • Paul Leake, Partner, Weil, Gotshal & Manges 3:30 pm Coffee Break 3:45 pm Discussion - The Response of the Private Sector Chair : Andres Solimano, Director, The World -

The European Balance of Payment Crisis

A joint initiative of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and the Ifo Institute JANUARY Forum 2012 VOLUME 13 SPECIAL ISSUE THE EUROPEAN BALANCE OF PAYMENTS CRISIS Edited by Hans-Werner Sinn CESifo Forum ISSN 1615-245X A quarterly journal on European economic issues Publisher and distributor: Ifo Institute Poschingerstr. 5, D-81679 Munich, Germany Telephone ++49 89 9224-0, Telefax ++49 89 9224-98 53 69, e-mail [email protected] Annual subscription rate: n50.00 Single subscription rate: n15.00 Shipping not included Editors: John Whalley ([email protected]) and Chang Woon Nam ([email protected]) Indexed in EconLit Reproduction permitted only if source is stated and copy is sent to the Ifo Institute www.cesifo-group.de Forum Volume 13, Special Issue January 2012 _____________________________________________________________________________________ THE EUROPEAN BALANCE OF PAYMENTS CRISIS The European Balance of Payments Crisis: An Introduction Hans-Werner Sinn 3 The Balance of Payments Tells Us the Truth Helmut Schlesinger 11 The Eurosystem in Times of Crises: Greece in the Role of a Reserve Currency Country? Wilhelm Kohler 14 The Euro in 2084 Charles B. Blankart 23 The Refinancing of Banks Drives Target Debt Manfred J.M. Neumann 29 The Current Account Deficits of the GIPS Countries and Their Target Debts at the ECB Peter Bernholz 33 Macroeconomic Imbalances in EMU and the Eurosystem Thomas Mayer, Jochen Möbert and Christian Weistroffer 35 The Derailed Policies of the ECB Georg Milbradt 43 Notes on the Target2 Dispute Stefan Homburg 50 Money, Capital Markets and -

US Debt Clock – $19.4 Trillion in Debt – $162K Per Tax Payer

Why “Plan B” Lessons from the Signs of a New Negative Rates Any Good News? Appendix / Survey Results 2008 / 2009 Crisis Global Crisis? = Trouble US Debt Clock – $19.4 Trillion In Debt – $162k Per Tax Payer www.usdebtclock.org Source: Aquaa Partners, 2016 69 Why “Plan B” Lessons from the Signs of a New Negative Rates Any Good News? Appendix / Survey Results 2008 / 2009 Crisis Global Crisis? = Trouble US GDP Growth Rate – Low and Flat % Source: Tradingeconomics.com Source: Aquaa Partners, 2016 70 Why “Plan B” Lessons from the Signs of a New Negative Rates Any Good News? Appendix / Survey Results 2008 / 2009 Crisis Global Crisis? = Trouble US - The US Economy Is Growing At Its Slowest Pace In Decades European companies and investors may be looking to the US for growth and yield, respectively, but the US economy is growing at its slowest pace in decades. This chart shows the average annualised growth rate of the past 11 US economic recoveries o The US economy has grown just 2.1% per year since 2009. That makes the current recovery by far the slowest since World War II o In Q2’16, the economy grew at an annualised rate of only 1.2%. That’s not even close to the average annualised growth rate of 4.7% of the last 10 recoveries Source: Aquaa Partners, 2016 Source: Commerce Department; WSJ, July 29, 2016 71 Why “Plan B” Lessons from the Signs of a New Negative Rates Any Good News? Appendix / Survey Results 2008 / 2009 Crisis Global Crisis? = Trouble US - 10-Year US Treasury Bond Yield (1790 to 2016) – At All-Time Low Elliott Management’s Paul Singer says this bond bubble is “the biggest bond bubble in world history.” June 1981 Feb. -

Hoover Digest

HOOVER DIGEST RESEARCH + OPINION ON PUBLIC POLICY SPRING 2020 NO. 2 THE HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was established at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the United States. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institution celebrates its centennial with a dual identity: an active public policy research center and an internationally recognized library and archives. The Institution’s overarching goals are to: » Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political, and social change » Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies » Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas that nurture the formation of public policy and benefit society Herbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of Stanford University continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in the twenty-first century: This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States, its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government. Both our social and economic systems are based on private enterprise, from which springs initiative and ingenuity. Ours is a system where the Federal Government should undertake no governmental, social, or economic action, except where local government, or the people, cannot undertake it for themselves. The overall mission of this Institution is, from its records, to recall the voice of experience against the making of war, and by the study of these records and their publication to recall man’s endeavors to make and preserve peace, and to sustain for America the safeguards of the American way of life. -

The Second Law of Economics the Frontiers Collection

THE SECOND LAW OF ECONOMICS THE FRONTIERS COLLECTION Series Editors: A.C. Elitzur L. Mersini-Houghton M.A. Schlosshauer M.P. Silverman J.A. Tuszynski R. Vaas H.D. Zeh The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active scientists in all areas to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, consciousness and complex systems – the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/5342 Reiner Kummel.. THE SECOND LAW OF ECONOMICS Energy, Entropy, and the Origins of Wealth 123 Reiner K¨ummel Institute for Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics University of W¨urzburg Am Hubland 97074 W¨urzburg Germany [email protected] Series Editors: Avshalom C. Elitzur Bar-Ilan University, Unit of Interdisciplinary Studies, 52900 Ramat-Gan, Israel email: [email protected] Laura Mersini-Houghton Dept. Physics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3255, USA email: [email protected] Maximilian A. Schlosshauer Niels Bohr Institute, Blegdamsvej 17, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark email: [email protected] Mark P. -

Social Banking and Social Finance: Answers to the Economic Crisis

SpringerBriefs in Business For other titles published in this series, go to http://www.springer.com/series/8860 Roland Benedikter Social Banking and Social Finance Answers to the Economic Crisis 123 Roland Benedikter Stanford University The Europe Center Stanford, CA, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7773-1 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7774-8 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London © Roland Benedikter 2011 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) For Ariane and Judith Foreword In this intellectually provocative volume, Roland Benedikter provides a lucid, cutting-edge treatment of the present-day process of banking and financing in the global economy. The description of the anatomy of the crisis of 2007–2010 is fol- lowed by a disquieting analysis of the many pathologies involved, which, if not cured, might jeopardize the stability of our model of Western democratic social order. -

The Collective Individual Households Or Coin Economic Theory

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The Collective Individual Households or Coin economic theory De Koning, Kees 24 October 2013 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/50967/ MPRA Paper No. 50967, posted 31 Oct 2013 04:31 UTC ________________________________________________________________________________ The Collective Individual Households or Coin Economic Theory Drs Kees De Koning 24 October 2013 ____________________________________________________________________ 1 Table of contents Page Introduction 3 1 A brief summary of the historical development of economic theories 4 2 Changes in saving patterns 2.1 Savings by individual households 6 2.2 Categories of savings by individual households 6 2.3 Relative growth of some individual savings categories 7 3 The Collective Individual Households or Coin economic theory 3.1 Introduction 8 3.2 The tenets of the Coin economic theory 8 3.2.1 Savings and the GDP level and savings and the collective individual households’ income level (first tenet) 9 3.2.2 The use and the users of savings (second tenet) 10 3.2.3 User groups and their savings and borrowings philosophy (third tenet) 11 3.2.4 Asset allocation and recession periods (fourth and fifth tenets) 14 3.2.4.1 The U.S. experience 15 3.2.5 Asset allocation and interest rates (sixth tenet) 18 3.2.6 Funding government debt (seventh tenet) 20 3.2.7 Corrective measures (eighth tenet) 22 3.2.8 Costs benefits structure for the financial sector companies (ninth tenet) 23 4 Possible adjustment measures 4.1 Economic easing 24 4.2 The flexi-tax 26 4.3 A “traffic light system” for home mortgages 26 4.4 A “traffic light system” for margin trading and short selling practices 27 4.5 A financial sector restructuring plan which puts individual households first 27 References 29 2 Introduction The collective individual households or coin economic theory aims to study how savings have been and are being allocated to the various asset classes and how they are being used. -

Counterclock # 4, When PR Passed the 2000 Issues Mark

many theories, ideas and fears for the future. I, for one, expected a great megapolis across the south of Sweden COUNTERCL CK and Denmark, where Copenhagen and Malmö is situ- ISSUE 10 FEBRUARY 2009 ated. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - For sure we would have a lunar base as in 1999! For A random fanzine by Wolf von Witting, Via Dei Banduzzi 6/4, sure we would have landed on Mars! It was questionable 33050 Bagnaria Arsa (Ud), Italy. Email: halluciraptor at gmail.com how far the mining operations in the asteroid belt had Assistant Editor: Floria Anca Marin, Bagnaria Arsa, Italy. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - come by the year 2000, but for sure it had been thought of. So I gathered. But no, really. I didn't expect any third world war to wipe most of us out. It didn't happen either. Yet. Also; the world is still far from overpopulated as in Soylent Green, where we are forced to eat our neigh- bours. The environment is being so gradually ruined from year to year, that we barely notice it. And the random occasions at which nature retaliates mostly hit remotely living people who we have little affinity to. My mode of travelling is low tech, since our time travel technology hasn't advanced far enough yet in my home era. But I prefer to be thorough in my research and considered it prudent to get started early and learn more along my way. I was 20 years old when I left the 70's behind to investigate the future. Since then I have had little reason to fast forward in time, since life has been full of interesting events and surprises. -

TÄTIGKEITSBERICHT Für Die Jahre 2012, 2013 Und 2014 2 TÄTIGKEITSBERICHT FÜR DIE JAHRE 2012 – 2014

1 TÄTIGKEITSBERICHT für die Jahre 2012, 2013 und 2014 2 TÄTIGKEITSBERICHT FÜR DIE JAHRE 2012 – 2014 Direktoren Prof. Dr. Armin von Bogdandy Prof. Dr. Anne Peters Heidelberg Revidierte Fassung vom 31. Dezember 2015 3 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. STRUKTUR UND GLIEDERUNG DES INSTITUTS ������������� 14 4 II. FORSCHUNGSPROGRAMM ����������������������� 21 A. Forschungskonzeption ......................................................................................................22 1. Übergreifende Forschungskonzeption .......................................................................................... 22 2. Forschungskonzeption von Armin von Bogdandy ......................................................................... 22 3. Forschungskonzeption von Anne Peters ..................................................................................... 23 4. Forschung in unabhängigen Gruppen.......................................................................................... 24 5. Forschungsgebiete ...................................................................................................................... 24 B. Forschung im Detail ........................................................................................................25 1. Allgemeines Völkerrecht .............................................................................................................. 25 a. Global Constitutionalism ........................................................................................................ 25 b. The Exercise of International -

Transformations of Public Sector and Its Financial System in Ukraine Volume 2 Public Finances and Financial Markets: International Trends and Ukrainian Experience

Transformations of public sector and its financial system in Ukraine Volume 2 Public finances and financial markets: international trends and Ukrainian experience Anatoli Bourmistrov Veronika Vakulenko (eds.) Nord University R&D-Report no. 54 Bodø 2020 Transformations of public sector and its financial system in Ukraine Volume 2 Public finances and financial markets: international trends and Ukrainian experience Anatoli Bourmistrov Veronika Vakulenko (eds.) Nord University R&D-Report no. 54 ISBN 978-82-821-1 ISSN 2535-2733 Bodø 2020 Introduction to the volume This research publication designed as a collection of scientific essays, gathering results from scientific cooperation of Norwegian, Ukrainian and international researchers participating in the following projects: “Norwegian-Ukrainian cooperation in a field of Public sector accounting, budgeting and finance Research Education (NUPRE)” (CPEA-LT-2017/10004) and “Norwegian- Ukrainian cooperation in Public Sector Economy Education: accounting, budgeting and finance (NUPSEE)” (CPEA-2015/10005). The second volume of the collection of scientific essays “Public finances and financial markets: international trends and Ukrainian experience” gathers different studies, e.g., three general reviews, a research paper and a viewpoint. The essays touch upon several interesting topics, they focus on multiple aspects of Ukrainian system of public finances and financial markets, analyse their development, point to existing problems and provide international examples of similar reforms. The first essay by Liubkina, Lyutyy and Onopko studies the transition of Ukrainian state-owned banks to IFRS 9 to understand how harmonization may influence the banks’ operations. The authors note that to ensure smooth transition to IFRS 9, new accounting and planning processes need to be created and appropriate evaluation methodology, databases and internal controls procedures are requested.