Macbeth and Hercules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OMC | Data Export

Joel Gordon, "Entry on: Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S03E01, S03E22): Mercenary / Atlantis by Sam Raimi, Robert Tapert, Christian Williams ", peer-reviewed by Elizabeth Hale and Lisa Maurice. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2020). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/1010. Entry version as of September 24, 2021. Sam Raimi , Robert Tapert , Christian Williams Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S03E01, S03E22): Mercenary / Atlantis USA/New Zealand TAGS: Aphrodite Ares Atlantis Cupid Daedalus Echidna Gods Greek mythology Hera Heracles / Herakles Hercules Hero Hero’s journey Icarus Iolaus Jason We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Series, S03E01, S03E22): Title of the work Mercenary / Atlantis Studio/Production Company MCA Television, Renaissance Pictures Country of the First Edition New Zealand, United States of America Country/countries of popularity United States of America, New Zealand, Australia Original Language English Season 3, Episode 1. “Mercenary”. Directed by Michael Hurst; Written by Robert Bielak. USA, Syndicated (MCA); September 30, 1996. 44 mins. First Edition Details Season 3, Episode 22. “Atlantis”. Directed by Gus Trikonis; Written by Roberto Orci & Alex Kurtzman. USA, Syndicated (MCA); May 12, 1997. 44 mins. Running time 44 mins. Format TV; subsequently VHS, DVD and digital streaming Date of the First DVD or VHS VHS January 8, 1999; DVD March 23, 2004 Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (Joseph LoDuca) won “Top TV Awards Series” in 1998 “ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards” Action and adventure fiction, B films, Mythological fiction, Genre Television series 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood.. -

Happily Ever Ancient

HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT This work is subject to an International Creative Commons License Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0, for a copy visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media First Edition, December 2020 ...still facing COVID-19. Editor: Asociación para la Investigación y la Difusión de la Arqueología Pública, JAS Arqueología Plaza de Mondariz, 6 28029 - Madrid www.jasarqueologia.es Attribution: In each chapter Cover: Jaime Almansa Sánchez, from nuptial lebetes at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Greece. ISBN: 978-84-16725-32-8 Depósito Legal: M-29023-2020 Printer: Service Pointwww.servicepoint.es Impreso y hecho en España - Printed and made in Spain CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: A CONTEMPORARY ANTIQUITY FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG AUDIENCES IN FILMS AND CARTOONS Julián PELEGRÍN CAMPO 1 FAMILY LOVE AND HAPPILY MARRIAGES: REINVENTING MYTHICAL SOCIETY IN DISNEY’S HERCULES (1997) Elena DUCE PASTOR 19 OVER 5,000,000.001: ANALYZING HADES AND HIS PEOPLE IN DISNEY’S HERCULES Chiara CAPPANERA 41 FROM PLATO’S ATLANTIS TO INTERESTELLAR GATES: THE DISTORTED MYTH Irene CISNEROS ABELLÁN 61 MOANA AND MALINOWSKI: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH TO MODERN ANIMATION Emma PERAZZONE RIVERO 79 ANIMATING ANTIQUITY ON CHILDREN’S TELEVISION: THE VISUAL WORLDS OF ULYSSES 31 AND SAMURAI JACK Sarah MILES 95 SALPICADURAS DE MOTIVOS CLÁSICOS EN LA SERIE ONE PIECE Noelia GÓMEZ SAN JUAN 113 “WHAT A NOSE!” VISIONS OF CLEOPATRA AT THE CINEMA & TV FOR CHILDREN AND TEENAGERS Nerea TARANCÓN HUARTE 135 ONCE UPON A TIME IN MACEDON. -

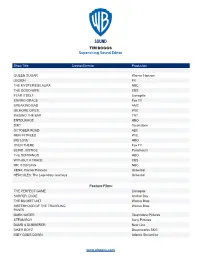

TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Feature Films

TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production QUEEN SUGAR Warner Horizon LEGION FX THE MYSTERIES/LAURA NBC THE GOOD WIFE CBS FEAR ITSELF Lionsgate SAVING GRACE Fox TV BREAKING BAD AMC GILMORE GIRLS. W.B. RAISING THE BAR TNT ENTOURAGE HBO DIRT Touchstone OCTOBER ROAD ABC MEN IN TREES W.B. BIG LOVE HBO OVER THERE Fox TV BLIND JUSTICE Paramount THE SOPRANOS HBO WITHOUT A TRACE CBS MR. STERLING NBC XENA: Warrior Princess Universal HERCULES: The Legendary Journeys Universal Feature Films: THE PERFECT GAME Lionsgate SURFER, DUDE Anchor Bay THE BUCKET LIST Warner Bros. SISTERHOOD OF THE TRAVELING Warner Bros. PANTS DARK WATER Touchstone Pictures STEAM BOY Sony Pictures DUMB & DUMBERER New Line BIKER BOYZ Dreamworks SKG IGBY GOES DOWN Atlantic Streamline www.wbppcs.com TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production WE WERE SOLDIERS Icon HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES Universal TRIXIE Sand Castle 5 Productions WALKING ACROSS EGYPT Mitchum Entertainment THE END OF VIOLENCE MGM THE LESSER EVIL Moon Dog Productions WASHINGTON SQUARE Hollywood Pictures LOST HIGHWAY October Films DEMON KNIGHT Universal ABOVE THE RIM New Line Cinema BLANK CHECK Disney HOUSE PARTY 3 New Line Cinema THE GLASS SHIELD Miramax DARKMAN III Universal DARKMAN II Universal Television/Cable Movies (Adr Supervisor) AMAZON HIGH Universal Home Ent. ANOTHER MIDNIGHT RUN Universal Television ASSAULT AT WEST POINT Showtime ATTACK OF THE 5’2’’ WOMAN Showtime BLIND JUSTICE HBO Pictures COLOR OF JUSTICE Showtime CONVICTION CBS THE COURTYARD Showtime DARK REFLECTIONS Fox FULL BODY MASSAGE Showtime FULL ECLIPSE HBO Pictures GANG IN BLUE Showtime HERCULES AND THE AMAZON Universal WOMEN HERCULES AND THE LOST KING- Universal DOM HERCULES AND THE CIRCLE OF Universal FIRE www.wbppcs.com TIM BOGGS Supervising Sound Editor Show Title Creator/Director Production HERCULES IN THE UNDERWORLD Universal HERCULES AND THE MAZE OF Universal THE MINOTAUR HERCULES: THE FIGHT FOR Universal Home Ent. -

Hercules Abstracts

Hercules: A hero for all ages Hover the mouse over the panel title, hold the Ctrl key and right click to jump to the panel. 1a) Hercules and the Christians ................................... 1 1b) The Tragic Hero ..................................................... 3 2a) Late Mediaeval Florence and Beyond .................... 5 2b) The Comic Hero ..................................................... 7 3a) The Victorian Age ................................................... 8 3b) Modern Popular Culture ....................................... 10 4a) Herculean Emblems ............................................. 11 4b) Hercules at the Crossroads .................................. 12 5a) Hercules in France ............................................... 13 5b) A Hero for Children? ............................................ 15 6a) C18th Political Imagery ......................................... 17 6b) C19th-C21st Literature ........................................... 19 7) Vice or Virtue (plenary panel) ............................... 20 8) Antipodean Hercules (plenary panel) ................... 22 1a) Hercules and the Christians Arlene Allan (University of Otago) Apprehending Christ through Herakles: “Christ-curious” Greeks and Revelation 5-6 Primarily (but not exclusively) in the first half of the twentieth century, scholarly interest has focussed on the possible influence of the mythology of Herakles and the allegorizing of his trials amongst philosophers (especially the Stoics) on the shaping of the Gospel narratives of Jesus. This -

Paul D Grinder

PAUL D GRINDER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR / PRODUCER / DIRECTOR / 2ND UNIT DIRECTOR PHONE (CAN) +1 778 955 6158 | (NZ) +64 27 275 9658 | EMAIL: [email protected] AGENT: AGENCY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (APA) | Anthony Marotto amarotto@apa‐agency.com PH: +1 310 888 4200 TOP TECHS: +61 02 9958 1611 / FILM CREWS PH : +64 09 632 1032 RESUME 1ST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR – 2021 M3GAN – Feature Film – Blumhouse (NZ/US) [ PREPPING AD] 2020 MURU – Feature Film – Oct 15 Productions (NZ) 2019 COWBOY BEBOP SEASON 1 – 10 Epsiode Series – Netflix (NZ/US) 2019 FAMTIME SEASON 1 – 10 Epsiode Series – Channel 7 (AUS) 2019 TRIANGLE PILOT – ABC / Disney (NZ/US) 2018/19 LOST IN SPACE SEASON 2 – 10 Epsiode Series – Legendary / Netflix (CA/US) 2017/2018 COLONY SEASON 3 – 13 Epsiode Series – Legendary / USA NETWORK (CA/US) 2017 LOST IN SPACE SEASON 1 – 10 Epsiode Series – Legendary / Netflix (CA/US) 2016/17 TIMELESS SEASON 1 – 15 Epsiode Series – Sony/NBC (CA/US) 2015/16 BLACK SAILS SEASON 4– 10 Epsiode Series – Starz Network (SA/US) 2014/15 BLACK SAILS SEASON 3– 10 Epsiode Series – Starz Network (SA/US) 2013/14 BLACK SAILS SEASON 2 – 10 Epsiode Series – Starz Network (SA/US) 2012/13 BLACK SAILS SEASON 1 – 8 Epsiode Series – Starz Network (SA/US) 2010 THE DOUBLE – 35mm Feature ‐ US‐ Hyde Park (US) 2009 SPARTACUS – BLOOD AND SAND – 13 Epsiode Series – Starz Network (NZ/US) (1st for first/pilot episode + Associate‐Producer /2nd Unit Director for the season) 2008 DISTRICT 9 ‐ HD (Red) Feature ‐ Wing Nut / QED / Sony (NZ/SA/US) (Also Director of 2nd Unit) 2007/2008 UNDERWORLD -

Rare Depiction of the Young Hercules Leads Christie’S Sale of Antiquities in April

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 6 M a r c h 2 0 1 4 RARE DEPICTION OF THE YOUNG HERCULES LEADS CHRISTIE’S SALE OF ANTIQUITIES IN APRIL London – The Christie’s sale of Antiquities in London on 2 April 2014 comprises 199 carefully selected lots with exceptional provenance which span the ancient world from the 3rd Millennium B.C. to the 11th Century A.D. Leading the sale is a rare statue of the young Hercules, formerly in the Roger Peyrefitte (1907-2000) Collection in Paris (estimate: £100,000-150,000, illustrated above). Peyrefitte was a French diplomat and noted novelist, whose collection, including this piece, was published in 1972. Further highlights include a pair of Egyptian alabaster canopic jars for Tau-Iert-Iru (estimate: £50,000 - 70,000) and a Roman marble Fortuna, previously in the collection at Harewood House (estimate: £25,000 - 35,000). With estimates ranging from £1,000 to £150,000 the sale is expected to realise in excess of £2 million. A playful nod to his exploits to come, the statue of the young Hercules shows him wearing the Nemean lion skin, which was won in his First Labour, and leaning on the iconic olive-wood club (now missing) (estimate: £100,000-150,000, illustrated left). The Romans followed the Greek taste for artistic renderings of infants, and representations of Hercules as a baby abound yet there are few depictions of the hero as a cherubically plump child evident in the present work. It is known from parallel examples that Hercules would have been holding the golden apples of the Hesperides in his outstretched left hand, which he was ordered to steal as his Eleventh Labour. -

Hercules: a Hero for All Ages

Hercules: A hero for all ages Hover the mouse over the panel title, hold the Ctrl key and right click to jump to the panel. 1a) Hercules and the Christians ................................... 1 1b) The Tragic Hero ..................................................... 3 2a) Late Mediaeval Florence and Beyond .................... 6 2b) The Comic Hero ..................................................... 7 3a) The Victorian Age ................................................... 8 3b) Modern Popular Culture ......................................... 9 4a) Herculean Emblems ............................................. 11 4b) Renaissance Literature ........................................ 13 5a) Hercules in France ............................................... 14 5b) A Hero for Children? ............................................ 16 6a) C18th Political Imagery ......................................... 18 6b) C19th-C21st Literature ........................................... 19 7a) Opera ................................................................... 21 7b) Vice or Virtue ........................................................ 22 8) Antipodean Hercules (plenary panel) ................... 24 1a) Hercules and the Christians Arlene Allan (University of Otago) Apprehending Christ through Herakles: “Christ-curious” Greeks and Revelation 5-6 Primarily (but not exclusively) in the first half of the twentieth century, scholarly interest has focussed on the possible influence of the mythology of Herakles and the allegorizing of his trials amongst -

Hercules Script Edit01

HERCULES…the MUSE-ICAL ACT I: Prologue.........................................The Storyteller The Gospel Truth (I)...................................The Muses The Gospel Truth (II)..................................The Muses Th Gospel Truth (III)..................................The Muses Go the Distance...................................Young Hercules Oh Mighty Zeus.........................................The Muses Go the Distance (reprise).........................Young Hercules One Last Hope...............................................Phil Zero to Hero...........................................The Muses I Won't Say (I'm In Love)....................................Meg A Star Is Born.................................The Muses/Company Track list: 1 “LONG AGO”..." - NARRATOR 2 THE GOSPEL TRUTH - MUSES 3 THE GOSPEL TRUTH II - MUSES 4 THE GOSPEL TRUTH III - MUSES 5 “GO THE DISTANCE’ - YOUNG HERCULES 6 OH MIGHTY ZEUS - MUSES 7 “”GO THE DISTANCE (Reprise) YOUNG HERCULES 8 “ONE LAST HOPE” - PHILOCTETES (PHIL) 9 “ZERO TO HERO" - MUSES plus Females 10 “I WON’T SAY I AM IN LOVE" - MEG & MUSES 11 “A STAR IS BORN" - MUSES / COMPANY 12 "Go the Distance (Single)" - Michael Bolton 13 The Big Olive (Score) 14 The Prophecy (Score) 15 Destruction of the Agora (Score) 16 Phil's Island (Score) 17 Rodeo (Score) 18 Speak of the Devil (Score) 19 The Hydra Battle (Score) 20 Meg's Garden (Score) 21 Hercules' Villa (Score) 22 All Time Chump (Score) 23 Cutting the Thread (Score) 24 A True Hero/A Star Is Born (End Title) - Lillias White, LaChanze, Roz Ryan, Cheryl Freeman, and Vanéese Y. Thomas After imprisoning the Titans beneath the ocean, the Greek gods gather to Mount Olympus for Zeus, and his wife Hera have a son named Hercules. While the other gods are joyful, Zeus' jealous brother Hades plots to overthrow Zeus and rule Mount Olympus. -

Paul-Dean Martin

An Adaptation By: Paul-Dean Martin 1 Cast List Young Hercules Adult Hercules Meg Phil Hades Pain Panic Zeus Hera Muse #1 Muse #2 Muse #3 Muse #4 Muse #5 Fate #1 Fate #2 Fate #3 Hermes Orpheus Narcissi Amphitryon Alceme 2 Narrator Long ago in the far away land of ancient Greece, there was a golden age of powerful gods and extraordinary heroes. And the greatest and strongest of all these heroes was the mighty Hercules. But what is the measure of a true hero? Now that is where our story.......... Muse #5 Will you listen to him, he’s making this story sound like some Greek tragedy? Muse #2 Lighten up, dude. Muse # 1 We’ll take it from here darling. Narrator You go girl. Muse #1 We are the muses’ goddesses of the arts and proclaimers of heroes. Muse #3 Heroes like Hercules. Muse #5 Honey, you mean Hunkules. OOOh I’d like to make some sweet music with him...... Muse #1 Our story actually begins long before Hercules, many eons ago. The Gospel Truth 1 Muses Back when the world was new The planet Earth was down on its luck And everywhere gigantic brutes called Titans ran amuck It was a nasty place There was a mess wherever you stepped Where chaos reigned and earthquakes and volcanoes never slept Chorus And then along came Zeus 3 Muses He hurled his thunderbolt Chorus He zapped Muses Locked those suckers in a vault Chorus They’re trapped Muses And on his own stopped chaos in its tracks Chorus And that’s the gospel truth Muses The guy was too type A to just relax And that’s the world’s first dish Zeus tamed the globe while still in his youth Though, honey it may seem impossble That’s the gospel truth Muses & Chorus On Mount Olympus life was neat And smooth as sweet vermouth Though, honey it may seem impossble That’s the gospel truth Muse 1 So, with the Titans safely locked away, the celebration of the century could begin. -

Season Two- Production Biographies

-SEASON TWO- PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES SAM RAIMI (EXECUTIVE PRODUCER) Sam Raimi has directed one the industry’s most successful film franchises ever—the blockbuster Spider-Man trilogy, which has grossed $2.5 billion at the global box office. All three films reside in the industry’s top 25 highest grossing titles of all time. In addition to the franchise’s commercial success, Spider-Man (2002) won that year’s People’s Choice Award as Favorite Motion Picture, earned a pair of Oscar® nominations (for VFX and Best Sound) and also collected two Grammy® nominations (for Best Score and Chad Kroeger’s song, “Hero”). The sequel, Spider-Man 2 (2004) won the Academy Award® for Best Visual Effects (with two more nominations, Best Sound and Sound Editing) and two BAFTA nominations (for VFX and Best Sound), among dozens of other honors. Most recently, Raimi is known for directing Oz the Great and the Powerful, a commanding prequel to one of Hollywood’s most beloved stories. Grossing nearly a quarter of a billion dollars at the worldwide box office, Oz has also been elected for awards across the board, including a nomination at the People’s Choice Awards for Favorite Family Movie, and winning Film Music at the BMI Film & TV Awards. Apart from creating one of Hollywood’s landmark film series, Raimi’s eclectic resume includes the gothic thriller The Gift, starring Cate Blanchett, Hilary Swank, Keanu Reeves, Greg Kinnear, and Giovanni Ribisi; the acclaimed suspense thriller A Simple Plan, which starred Bill Paxton, Billy Bob Thornton, and Bridget Fonda (for which Thornton earned an Academy Award® nomination for Best Supporting Actor and Scott B. -

The Analysis of Hercules Journey in Hercules (2014)

THE STAGES TO BE A HERO: THE ANALYSIS OF HERCULES JOURNEY IN HERCULES (2014) MOVIE A GRADUATING PAPER Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Gaining the Bachelor Degree in English Literature By: Totok Zunianto 09150036 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ADAB AND CULTURAL SCIENCES SUNAN KALIJAGA STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 HALAMAN PENGESAHAN iii KEMENTRIAN AGAMA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SUNAN KALIJAGA FAKULTAS ADAB DAN ILMU BUDAYA Jl. Marsda Adisucipto Yogyakarta 55281 Telp./Fak. (0274) 513949 Web: http://adab.uin-suka.ac.id E-mail: [email protected]. NOTA DINAS Hal : Skripsi a.n. Totok Zunianto Yth. Dekan Fakultas Adab dan Ilmu Budaya UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta Assalamualaikum wr.wb Setelah memeriksa, meneliti, dan memberikan arahan untuk perbaikan atas skripsi saudara: Nama : Totok Zunianto NIM : 09150036 Prodi : Sastra Inggris Fakultas : Adab dan Ilmu Budaya Judul : The Stages to be a Hero: The Analysis of Hercules Journey in Hercules (2014) Movie Saya menyatakan bahwa skripsi tersebut sudah dapat diajukan pada sidang Munaqosyah untuk memenuhi sebagai syarat memperoleh gelar Sarjana Sastra Inggris. Atas perhatian yang diberikan, saya ucapkan terimakasih. Wassalamu’alaikum wr.wb Yogyakarta, 6 Juni 2016 Pembimbing Danial Hidayatullah, M.Hum NIP 19760405 200901 1 016 iv ABSTRAK Judul skripsi ini adalah The Stages to be a Hero: The Analysis of Hercules Journey in Hercules (2014) Movie. Penulis memilih untuk membahas perjalanan menjadi pahlawan yang dilakukan oleh karakter Hercules dalam film tersebut karena karakternya digambarkan dengan cara yang unik yaitu dia disajikan sebagai tokoh yang terusir dengan tuduhan sebagai pembunuh istri dan anak- anaknya sendiri. Penulis memilih film Hercules karena Hercules adalah tokoh yang paling terkenal dari Mitos Yunani sampai sekarang ini. -

Una Guía De Cine, Televisión, Literatura De Masas E Internet (1900-2012), Y Su Aprovechamiento En La Clase De

FACULTAD DE TRADUCCIÓN E INTERPRETACIÓN Programa de Doctorado: Español y su cultura: investigación, desarrollo e innovación. Hércules en la cultura popular contemporánea: una guía de cine, televisión, literatura de masas e internet (1900-2012), y su aprovechamiento en la clase de Español LE/L2 TESIS DOCTORAL Realizada por Dña. Mª Carmen Santana Alfonso V°B° Dr. D. Gregorio Rodríguez Herrera Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2014 1 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS La realización de esta tesis me ha aportado un gran enriquecimiento cultural y, a pesar de que toda tesis conlleva una considerable dedicación, ha resultado ser una experiencia muy positiva. Es cierto que es un camino solitario, pero con la ayuda de las personas queridas se puede llevar a cabo. Es por ello que quiero mostrar mi agradecimiento a todas las personas de mi entorno que me han apoyado durante este difícil y largo proceso. Deseo agradecer a mi tutor y guía en esta tesis, el Dr. Gregorio Rodríguez Herrera, su atención, su apoyo y sus acertados consejos, pues sin su ayuda no habría sido posible la realización de este proyecto. Quiero expresar mi gratitud a mis familiares y, en especial, a mi pareja por su comprensión y su incondicional apoyo en los momentos más difíciles durante la elaboración de esta tesis. También transmito mi agradecimiento al personal de la Biblioteca Universitaria de esta universidad, a los profesores que se encargaron de repartir la encuesta a los estudiantes extranjeros de ERASMUS y a estos últimos por su participación y colaboración. 3 4 Índice 0. Introducción 11-13 1. Leyenda de Hércules 17-54 2.