101843 WEMA Polska Czechy.Pdp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entries WAG AARHUS 2006-AA

NOMINATIVE ENTRIES WOMEN'S ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS 39th Artistic Gymnastics World Championships AARHUS (DEN), 2006 Category Fed/Name Birth Yr All Around 50041 ARG DOMENEGHINI Nadir 1990 16 50044 ARG FICOSECCO Eugenia 1987 19 50042 ARG FRATANTUENO Agostina 1989 17 18058 ARG GONZALEZ Aylen 1989 17 17229 ARG POLIANDRI Sol 1988 18 50043 ARG POTOCHNIK Tatiana 1990 16 50072 AUS BONORA GEORGIA 1990 16 19316 AUS DYKES Hollie 1990 16 50071 AUS HERNANDEZ Melody 1990 16 19313 AUS JOURA Daria 1990 16 50132 AUS MORGAN Shona 1990 16 17555 AUS NGUYEN Karen 1987 19 18665 AUS VIVIAN Olivia 1989 17 16094 AUT HASENOEHRL Carina 1988 18 16095 AUT MAYER Sandra 1988 18 17068 BEL HENRY Chloé 1987 19 16890 BEL VANWALLEGHEM Aagje 1987 19 17079 BLR DMITRANITSA Liudmila 1989 17 18696 BLR LARINA Tatsiana 1989 17 17077 BLR MAKSHTAROVA Viktoria 1990 16 17075 BLR MARACHKOUSKAYA Nastassia 1990 16 13442 BLR NOVIKAVA Aksana 1987 19 50040 BLR SHAKOTS Volha 1990 16 16102 BLR SYCHEUSKAYA Alina 1988 18 50067 BRA CHAVES SANTOS Juliana 1990 16 13159 BRA COMIN Camila 1983 23 18053 BRA DA COSTA Bruna 1989 17 13160 BRA DOS SANTOS Daiane 1983 23 13161 BRA HYPOLITO Daniele 1984 22 16234 BRA SOUZA Lais 1988 18 17083 BUL GEORGIEVA Silvia 1990 16 16289 BUL HRISTOVA Veneta 1988 18 17080 BUL IOTOVA Suzana 1987 19 1097 BUL KARPENKO Victoria 1981 25 18543 BUL STANKOVA Mariana 1990 16 13386 BUL TANKOUCHEVA Nikolina 1986 20 *=Reserve gymnast Updated 29.09.2006 15:02:28 Page 1/7 NOMINATIVE ENTRIES WOMEN'S ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS 39th Artistic Gymnastics World Championships AARHUS (DEN), 2006 Category -

ASIAN GAMES RESULTS in ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS (Women) 1974 – 2010 by DR

ALL ASIAN GAMES RESULTS IN ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS (women) 1974 – 2010 BY DR. SALIH AL-AZAWI IRAQI GYMNASTICS FEDERATION Year Place Gold Silver Bronze 2010 Guangzhou(CHN) China (CHN) Japan (JPN) UZBEKISTAN(UZB) 2006 Doha (QAT) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) 2002 Busan (KOR) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) 1998 Bangkok (THA) China (CHN) Japan (JPN) Kazakhstan (KAZ) 1994 Hiroshima (JPN) China (CHN) Japan (JPN) Korea (KOR) 1990 Beijing (CHN) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Korea (KOR) 1986 Seoul (KOR) China (CHN) Korea (KOR) Japan (JPN) 1982 New Delhi (IND) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) 1978 Bangkok (THA) China (CHN) DPR Korea (PRK) Japan (JPN) All around All Asian Games Medallists Women Year Place Gold Silver Bronze HUANG 2010 Guangzhou(CHN) SUI Lu(CHN) TANAKA Rie(JPN) Qiushuang(CHN) HONG Su Jong 2006 Doha (QAT) HE Ning (CHN) ZHOU Zhuoru (CHN) (PRK) ZHANG Nan CHUSOVITINA Oxana 2002 Busan (KOR) KANG Xin (CHN) (CHN) (UZB) YEVDOKIMOVA Irina SUGAWARA Risa 1998 Bangkok (THA) LIU Xuan (CHN) (UZB) (JPN) 1994 Hiroshima (JPN) QIAO Ya (CHN) YUAN Kexia (CHN) MO Huilan (CHN) CHEN Cuiting KIM Gwang-Suk 1990 Beijing (CHN) LI Yifang (CHN) (CHN) (PRK) CHEN Cuiting 1986 Seoul (KOR) HUANG Qun (CHN) YU Feng (CHN) (CHN) CHEN Yongyan CHOE Jong Sil 1982 New Delhi (IND) WU Jiani (CHN) (CHN) (PRK) HO Hsiumin LIU Yachun (CHN) 1978 Bangkok (THA) (CHN) CHU Cheng (CHN) CHIANG S-Y. 1974 Tehran (IRI) NING H-L. (CHN) HSIN K-C. (CHN) (CHN) Vault All Asian Games Medallists Women Year Place Gold Silver Bronze HUANG OZAWA 2010 Guangzhou(CHN) TANAKA Rie(JPN) -

Red Men's NEW BINGO

T P4CE STXTEEJT ‘«U^DAY, JIEBRUABY i i a t t r l f » 0trr £trrafttg IfrraU i Tha Wasther Average Daily Net Press Run raraeaat af U. S. Waatbat Baieaa For Uw Maath aS Fabraary, 1S4B M n.. Louis Pack, o f Trumbull, OIbbona Aaaemhiy, Catholic La? bid filing data may ba granted. A l Snovr finrriaa, Mapwtag aui4 4rlft- ready the ar^itecta, as la usual, will give a ten-mlhute talk on the dies o f Columbus, will hold a buai- Manchester Boy Aboard School Plans ing oaow tUa aftarooaai partly About Town federation of Women’s Clubs, pre neas meeting ’Tuesday at 8 o'clock Light Cruiser Manchester have supplemented the original specificaUons with minor amend cleuSy Jaalght aa4 We4neaSe>i ceding the program at the meeting at the K. o f C. home. Rev. Robert 9,713 ments' which are to go to those in Bsuat eoMar taaiglit; tiaah wlaia. of the Women’s Club, Monday eve Carroll w ill speak on CTO. In con Robert B, Kant, seaman, Topic Tonight .Maoibar a< tha A a ilt tliM Anne ICcAdame of IS Onk terested in construction. ning. Bela Urban, concert violinist, nection with the Commtmity Serv U 8 N, oon of Mr. and Mra. W il ■trwt lima returned from n month’a General Manager George H. BnswM aC OtieUlatlaBa w ill be the feature of the evening. ice program,. members are asked liam R. Kent of 33 Palm street, Manehe$ter— A City of Village Charm ^••onUon epcnt In Miami, Florida. to bring old sheets and cloth for Waddell has stated that he will Mrs. -

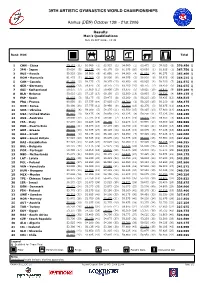

39TH ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Aarhus (DEN) October 13Th

39TH ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Aarhus (DEN) October 13th - 21st 2006 Results Women’s Individual All-Around Final THU 19 OCT 2006 - 19:30 NOC RankBib Name Total Code 1363 FERRARI VanessaITA 14.800 15.825 14.900 15.500 61.025 2391 BIEGER Jana USA 14.725 15.350 15.300 15.375 60.750 3472 IZBASA Sandra RalucaROM 15.025 14.225 15.475 15.525 60.250 4474 NISTOR Steliana ROM 14.275 15.275 15.800 14.600 59.950 5113 JOURA Daria AUS 14.500 15.100 15.000 15.275 59.875 6194 PANG Panpan CHN 14.025 15.425 14.800 15.425 59.675 7111 DYKES Hollie AUS 14.350 14.975 15.625 14.550 59.500 8294 TWEDDLE ElizabethGBR 14.550 14.700 14.950 15.250 59.450 9303 CHUSOVITINA OksanaGER 15.000 14.700 14.375 14.875 58.950 10396 PRIESS Ashley USA 14.450 15.425 15.325 13.600 58.800 11285 SEVERINO IsabelleFRA 14.600 14.100 14.925 15.000 58.625 12196 ZHOU Zhuoru CHN 14.300 15.150 14.425 14.700 58.575 13403 KOZICH Alina UKR 14.500 13.875 15.175 14.650 58.200 14250 CAMPOS Laura ESP 14.825 14.550 14.575 14.150 58.100 15371 KURODA Mayu JPN 13.400 15.550 15.100 13.925 57.975 16174 HOPFNER-HIBBS ElyseCAN 13.950 14.325 15.125 14.300 57.700 16251 DE SIMONE LenikaESP 13.725 14.900 14.650 14.425 57.700 18495 KAESLIN Ariella SUI 13.575 14.675 15.075 14.350 57.675 19486 PAVLOVA Anna RUS 14.925 13.900 14.225 14.575 57.625 20281 LINDOR KatheleenFRA 14.450 14.125 14.725 14.300 57.600 21154 HYPOLITO DanieleBRA 13.750 14.150 14.575 14.700 57.175 22408 ZGOBA Dariya UKR 13.650 15.600 14.075 13.600 56.925 23451 HONG Su Jong PRK 15.700 13.350 13.275 13.750 56.075 24487 PRAVDINA KristinaRUS 13.675 13.275 14.850 13.725 55.525 Legend Vault Uneven Bars Beam Floor Note: Underlined totals indicate starting apparatus. -

Artistic Gymnastics Results 1961 - 2009

ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS RESULTS 1961 - 2009 Men's All-Around Year Gold Silver Bronze Takashi Mitsukuri, 1961 Yuriy Titov, URS Velik Kapsasov, BUL JPN Matsumoto Masatake, 1963 Kato Takeshi, JPN Hayata Takuji, JPN JPN Akinori Nakayama, 1965 Miroslav Cerar, YUG Makoto Sakamoto, USA JPN Akinori Nakayama, 1967 Takeshi Kato, JPN Sawao Kato, JPN JPN Terouichi Okamura, 1970 Ryuji Fujimori, JPN Vyacheslav Fogel, URS JPN Nikolay Andrianov, Vladimir Shchukine, 1973 Vladimir Safronov, URS URS URS Vladimir Markelov, 1977 Hirashi Kajiyama, JPN Vladimir Tichonov, URS URS Fedor Kulaksizov, Sergey Khishniyakov, 1979 Bogdan Makuts, URS URS URS Yuriy Korolev, URS 1981 --- Artur Akopeam, URS Kurt Szilier, ROM Vladimir Artemov, Aleksandr Pogorelov, 1983 Yuriy Korolev, URS URS URS Hiroyuki Okabe, JPN Dmitriy Bilozerchev, Valentin Mogilniy, 1985 Mitsuaki Watanabe, URS URS JPN Wang Zongsheng, Daisuke Nishikawa, Masayuki Matsunaga, 1991 CHN JPN JPN Igor Korobchinskiy, 1993 Vitaliy Scherbo, BLR Juri Chechi, ITA UKR Yevgeniy Chabayev, 1995 Jung Jin-Soo, KOR Cristian Leric, ROM RUS 1997 Zheng Lihui, CHN Zhao Shen, CHN Wang Dong, CHN Oleksandr Beresh, Nikolay Kryukov, 1999 Erick Lopez, CUB UKR RUS Tomita Hiroyuki, JPN 2001 Yang Wei, CHN Tsukahara Naoya, --- JPN Yernar Yerimbetov, 2003 Yang Tae-Young, KOR Yuki Yoshimura, JPN KAZ 2005 Hiroyuki Tomita, JPN Kim Dae-Eun, KOR Takehiro Kashima, JPN 2007 Hisashi Mizutori, JPN Guo Weiyang, CHN Koki Sakamoto, JPN 2009 Yosuke Hoshi, JPN Wang Heng, CHN Kim Soo-Myun, KOR Men's Horizontal Bar Year Gold Silver Bronze Vladimir Shchukine, -

Preliminary Technical Program Schedule

1 PRELIMINARY TECHNICAL PROGRAM SCHEDULE Monday, September 30, 12:30PM-2:10PM Wind Systems Monday, September 30, 12:30PM-2:10PM, Room: 344, Chair: Qiang Wei, Hengzhao Yang 12:30PM Remote Monitoring and Diagnostics of Pitch 1:20PM Maximum Power Point Tracking for Wind Bearing Defects in a MW-Scale Wind Turbine Using Turbine Using Integrated Generator-Rectifier Systems Pitch Symmetrical-component Analysis [#19010] [#20013] Lijun He, Liwei Hao and Wei Qiao, GE Research, Phuc Huynh, Samira Tungare and Arijit Banerjee, United States; University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States States 12:55PM LVRT Control of Back-to-Back Power 1:45PM Simple Empiric Root-Mean-Square Converter PMSG Wind Turbine Systems: an FPGA Electric-Drivetrain Model for Wind Turbines with Based Hardware-in-the-Loop Solution [#19069] Full-Size Converter [#20015] Zhenkun Zhang, Zhenbin Zhang, Xiaodong Liu, Daniel von den Hoff, Denise Cappel, Abdul Baseer, Quanrui Hao and Zhiwei Zhang, Shandong University, Rik W. De Doncker and Ralf Schelenz, PGS, E.On China; The Ohio State University, United States ERC, RWTH Aachen University, Germany; CWD, RWTH Aachen University, Germany Grid-Forming Converters Monday, September 30, 12:30PM-2:10PM, Room: 342, Chair: Xiongfei Wang, Yenan Chen 12:30PM Small-Signal Modeling, Stability Analysis, 1:20PM Active Power Reserve Control for and Controller Design of Grid-Friendly Power Grid-Forming PV Sources in Microgrids using Converters with Virtual Inertia and Grid-Forming Model-based Maximum Power Point Estimation Capability [#19775] [#19592] Han Deng, Jingyang Fang, Jiale Yu, Vincent Zhe Chen, Robert H. Lasseter and Thomas M. -

Gymnastics Results

Gymnastics Results SHENZHEN BAO'AN GYMNASIUM ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS 深圳市宝安区体育馆 竞技体操 MEN'S QUALIFICATION AND TEAM COMPETITION 男子资格赛&团体决赛 SUN 星期日 14 AUG 2011 TEAM 18:20 团体 MEDALLISTS 获奖名单 Medal C/R Names HOJO Yodai GOLD JPN Japan ISHIKAWA Hiroki SEJIMA Ryuzo YAMAMOTO Masayoshi YAMAMOTO Shoichi CHEN Xuezhang SILVER CHN China CHENG Ran LIU Rongbing WANG Guanyin YANG Shengchao BATAGA Cristian BRONZE ROU Romania BERBECAR Marius BUIDOSO Ovidiu COTUNA Vlad KOCZI Flavius GAM400000_C92B 1.0 Report Created SUN 14 AUG 2011 20:49 Page 1/1 SHENZHEN BAO'AN GYMNASIUM ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS 深圳市宝安区体育馆 竞技体操 MEN'S INDIVIDUAL ALLAROUND FINAL 男子个人全能决赛 MON 星期一 15 AUG 2011 19:00 RESULTS 比赛成绩 Rank Bib Name C/R Total 1 250 KUKSENKOV M. UKR 14.800 14.900 14.200 15.650 14.550 14.950 89.050 2 185 YAMAMOTO S. JPN 14.750 14.550 14.100 15.250 15.550 14.700 88.900 3 119 GAFUIK N. CAN 14.850 13.450 13.800 16.050 15.050 15.150 88.350 4 128 LIU R. CHN 14.400 14.850 14.150 15.700 14.350 14.250 87.700 5 196 LEE H. KOR 14.050 14.750 13.850 15.450 14.500 14.150 86.750 6 187 GORBACHEV S. KAZ 14.600 13.200 13.900 15.650 14.200 14.350 85.900 7 120 SANDY C. CAN 14.550 14.150 13.050 15.400 14.400 14.250 85.800 8 140 GOMEZ FUERTES J. ESP 14.750 12.850 14.400 15.500 14.750 13.450 85.700 8 163 FIRTH M. -

Qualification Team Results

39TH ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Aarhus (DEN) October 13th - 21st 2006 Results Men’s Qualifications SUN 15 OCT 2006 - 19:30 Rank NOC Total 1 CHN - China 59.125 (11) 62.000 (1) 62.925 (2) 64.900 (1) 62.475 (2) 59.025 (8) 370.450 Q 2 JPN - Japan 59.650 (8) 59.275 (4) 62.175 (3) 61.975 (20) 63.050 (1) 61.625 (1) 367.750 Q 3 RUS - Russia 59.525 (10) 58.800 (6) 61.650 (4) 64.000 (4) 61.050 (4) 60.375 (2) 365.400 Q 4 ROM - Romania 61.475 (1) 60.200 (2) 59.800 (6) 64.075 (3) 59.900 (9) 58.875 (9) 364.325 Q 5 CAN - Canada 61.250 (2) 58.775 (7) 58.375 (15) 63.650 (6) 60.825 (6) 59.100 (7) 361.975 Q 6 GER - Germany 58.900 (13) 59.675 (3) 59.175 (12) 63.100 (10) 60.775 (7) 59.450 (5) 361.075 Q 7 SUI - Switzerland 59.675 (7) 57.950 (11) 59.400 (10) 63.675 (5) 59.625 (10) 58.875 (9) 359.200 Q 8 BLR - Belarus 58.625 (15) 57.125 (17) 60.150 (5) 62.800 (13) 60.950 (5) 59.525 (4) 359.175 Q 9 ESP - Spain 61.025 (3) 58.175 (9) 59.475 (8) 63.200 (9) 58.225 (15) 58.425 (12) 358.525 10 FRA - France 60.850 (5) 57.575 (14) 57.925 (17) 64.700 (2) 58.225 (15) 59.200 (6) 358.475 11 KOR - Korea 58.100 (18) 57.775 (12) 59.450 (9) 62.200 (18) 62.275 (3) 58.675 (11) 358.475 12 UKR - Ukraine 60.325 (6) 59.200 (5) 59.275 (11) 62.550 (15) 59.125 (13) 57.800 (14) 358.275 13 USA - United States 61.025 (3) 58.475 (8) 59.050 (14) 63.225 (8) 59.200 (11) 57.125 (20) 358.100 14 AUS - Australia 59.000 (12) 57.725 (13) 59.500 (7) 61.875 (23) 58.475 (14) 59.600 (3) 356.175 15 ITA - Italy 57.275 (22) 55.225 (23) 63.100 (1) 62.275 (17) 57.975 (17) 56.650 (22) 352.500 -

International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering Glasgow, Scotland June 9–14, 2019

Glasgow 38th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering Glasgow, Scotland June 9–14, 2019 OFFSHORE MECHANICS AND ARCTIC ENGINEERING Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering EDITOR: Lance Manuel, PhD The University of Texas at Austin, USA OMAEOMAE 20192019 ConferenceConference Attendees:Attendees: AccessAccess andand DownloadDownload ArticlesArticles ofof InterestInterest FREE!FREE! OMAE 2019 Conference attendees will have access to view and download articles FREE from the Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering from June 15, 2019 – September 15, 2019. It’s Simple, Get Started! Visit Journal of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering on The ASME Digital Collection (offshoremechanics.asmedigitalcollection.asme.org) and click on any article. For queries or support, contact Sharon Giordano: [email protected] ® ASME® TABLE OF CONTENTS YOUR HOSTS Program at a Glance ....................... 2 TECHNICAL PROGRAM Technical Tours ............................... 87 Floor Plans ........................................... 4 Honoring Symposia ...................... 21 Outreach for Engineers .............. 88 Welcome Letters ............................... 6 Afternoon Lecture Series .......... 22 OMAE 2020 ........................................ 89 Glasgow Map .................................... 10 Saturday, June 8 ............................. 23 Listing of Committees & Award Winners ................................ 12 Sunday, June 9 ................................ 24 Organizers ......................................... -

Gymnastique Artistique

UNIVERSITY SPORTS 77 MAGAZINE EXCELLENCE IN MIND AND BODY UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE SPORTS 77 EXCELLENCE IN MIND AND BODY EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 04 The president’s Message / Message du Président President 06 General Assembly / Assemblée Générale KILLIAN George E. (USA) First Vice-President 10 Tandem Project / Le projet Tandem GALLIEN Claude-Louis (FRA) 14 Universiade 2009 Belgrade Vice-Presidents BERGH Stefan (SWE) 20 Athletics - Athlétisme CABRAL Luciano (BRA) CHIKH Hassan (ALG) 26 Artistic Gymnastics - Gymnastique artistique ZHANG Xinsheng (CHN) 30 Rhythmic Gymnastics - Gymnastique rythmique Treasurer BAYASGALAN Danzandorj (MGL) 34 Judo Fencing - Escrime First Assessor 38 RALETHE Malumbete (RSA) 42 Table Tennis - Tennis de table Assessors AL-HAI Omar (UAE) 46 Tennis BURK Verena (GER) CHEN Tai-Cheng (TPE) SOMMAIRE 50 Swimming - Natation DIAS Pedro (POR) DOUVIS Stavros (GRE) 56 Diving - Plongeon DYMALSKI Marian (POL) EDER Leonz (SUI) 60 Waterpolo JASNIC Sinisa (SRB) IGARASHI Hisato (JPN) 64 Basketball KABENGE Penninah (UGA) KIM Chong Yang (KOR) 68 Volleyball MATYTSIN Oleg (RUS) ODELL Alison (GBR) 72 Football TAMER Kemal (TUR) ULP Kairis (EST) 76 Archery - Tir à l’arc 82 Taekwondo Continental Associations Delegates CHOW Kenny (HKG) Asia-AUSF 86 Participation GUALTIERI Alberto (ITA) Europe-EUSA JAKOB Julio (URU) America-ODUPA 90 FISU Conference / Conférence FISU LAMPTEY Silvanus (GHA) Africa-FASU NELSON Karen (SAM) Oceania-OUSA 98 FISU Development Policy / Politique de développement de la FISU Auditor 102 FISU Webgames GAGEA Adrian (ROU) 104 Winter Universiade 2011 Erzurum Universiade d’Hiver CONTENTS Secretary General / CEO SAINTROND Eric (BEL) 106 Universiade 2011 Shenzhen ©Publisher 108 Winter Universiade 2013 Maribor Universiade d’Hiver FISU AISBL Château de la Solitude 109 Universiade 2013 Kazan Avenue Charles Schaller, 54 1160 Brussels/Belgium 110 Winter Universiade 2015 Granada Universiade d’Hiver Tel. -

39Th Artistic Gymnastics World Championships

39TH ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Aarhus (DEN) October 13th - 21st 2006 Data-Handling by: Contact: [email protected] - [email protected] 39TH ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Aarhus (DEN) October 13th - 21st 2006 Number of Entries by NOC As of SAT 21 OCT 2006 Number of Gymnasts NOC NOC Code Men Women Total ALG Algeria 6 - 6 ARG Argentina - 6 6 ARM Armenia 2 - 2 AUS Australia 7 7 14 AUT Austria 7 2 9 AZE Azerbaijan 1 - 1 BEL Belgium 1 2 3 BLR Belarus 7 7 14 BRA Brazil 6 6 12 BUL Bulgaria 7 7 14 CAN Canada 7 6 13 CHI Chile 7 5 12 CHN China 7 7 14 COL Colombia 3 3 6 CRO Croatia 3 3 6 CYP Cyprus 2 - 2 CZE Czech Republic 6 6 12 DEN Denmark 7 7 14 EGY Egypt 6 2 8 ESP Spain 7 7 14 EST Estonia - 1 1 FIN Finland 7 6 13 FRA France 6 6 12 GBR Great Britain 7 7 14 GER Germany 6 7 13 GRE Greece 7 6 13 HUN Hungary 7 2 9 IRL Ireland 1 2 3 ISL Iceland 6 4 10 ISR Israel 4 3 7 ITA Italy 7 6 13 JPN Japan 7 7 14 KAZ Kazakhstan 7 - 7 KOR Korea 7 7 14 LAT Latvia 6 1 7 LTU Lithuania 2 2 4 LUX Luxembourg 1 - 1 MAS Malaysia 1 - 1 MEX Mexico 6 6 12 NED Netherlands 7 6 13 NOR Norway 7 5 12 NZL New Zealand 2 - 2 POL Poland 6 6 12 POR Portugal 6 - 6 PRK DPR Korea - 6 6 PUR Puerto Rico 6 5 11 ROM Romania 7 6 13 RSA South Africa 6 2 8 RUS Russia 7 7 14 SLO Slovenia 7 2 9 GA0000000_30 1.0 Report Created SAT 21 OCT 2006 14:29 Page 1/2 39TH ARTISTIC GYMNASTICS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Aarhus (DEN) October 13th - 21st 2006 Number of Entries by NOC As of SAT 21 OCT 2006 Number of Gymnasts NOC NOC Code Men Women Total SUI Switzerland 7 6 13 SVK -

Results Book Gymnastics Artistic

Results Book Gymnastics Artistic Data Handling by BELGRADE FAIR HALL 1 GYMNASTICS ARTISTIC COMPETITION SCHEDULE As of WED 1 JUL 2009 Date Time Event THU 2 JUL Women's Team Competition 14:30 Women's Team Final & Individual Qualification 16:00 Women's Team Final & Individual Qualification 17:30 Women's Team Final & Individual Qualification 19:00 Women's Team Final & Individual Qualification FRI 3 JUL Men's Team Competition 10:00 Men's Team Final & Individual Qualification 11:40 Men's Team Final & Individual Qualification 15:00 Men's Team Final & Individual Qualification 16:40 Men's Team Final & Individual Qualification 18:20 Men's Team Final & Individual Qualification SAT 4 JUL AllAround Final 15:00 Women AllAround Final 19:00 Men AllAround Final SUN 5 JUL Apparatus Final 16:00 Men's Floor Final 16:30 Pommel Horse Final 16:30 Women's Vault Final 17:00 Rings Final 17:00 Uneven Bars Final 18:30 Men's Vault Final 19:00 Beam Final 19:00 Parallel Bars Final 19:30 Women's Floor Final 19:30 High Bar Final Note: Schedule is subject to change GA0000000_C08 1.0 Report Created WED 1 JUL 2009 12:26 Page 1/1 BELGRADE FAIR HALL 1 GYMNASTICS ARTISTIC NUMBER OF ENTRIES BY NOC As of WED 1 JUL 2009 Number of Gymnasts NOC Men Women Total Albania 1 1 Austria 1 1 2 Belgium 5 5 Belarus 1 1 Brazil 5 1 6 China 5 5 10 Croatia 1 1 2 Cyprus 2 2 4 Czech Republic 2 2 Egypt 4 4 8 Spain 2 2 Finland 5 5 France 5 5 Great Britain 5 5 10 Greece 3 3 Hong Kong 1 1 Hungary 5 1 6 Israel 1 1 2 Japan 5 5 10 Kazakhstan 4 4 Korea 5 5 10 Saudi Arabia 1 1