BSO 82-2 Bookreviews 363..364

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa Glaire D

Al-Masāq Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean ISSN: 0950-3110 (Print) 1473-348X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/calm20 The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick, and Mariam Rosser-Owen (Eds), 2018, [Handbook of Oriental Studies / Handbuch der Orientalistik, Section 1: The Near and Middle East, volume 122], Leiden and Boston: Brill, xxxviii + 688 pp., 18 maps, 203 ill. b/w, 10 tables, €189.00/US$218.00 (hardback), ISBN 9-789004-355668 Kordula Wolf To cite this article: Kordula Wolf (2019) The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa, Al-Masāq, 31:3, 376-381, DOI: 10.1080/09503110.2019.1662605 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09503110.2019.1662605 Published online: 04 Sep 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 38 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=calm20 376 BOOK REVIEWS Perhaps Drayson’s most impressive contribution to this study is her analysis of the way in which memory has been preserved in fictional accounts that have proliferated down the cen- turies and in contrasting popular myth and the expressions of sorrow that have become part of a haunting splendour that is still tangible. And Drayson notes, the passionate grief expressed by the Andalusi poets following Boabdil’s exile attaches no blame to the young monarch himself. Nevertheless, perceptions such as his weakness and apparent incapacity were to emerge in some frontier ballads such as The Ballad of the Boy King, and this allowed erroneous confusion to have an impact on his reputation, which was perpetuated by sixteenth-century Spanish writers such as the Murcian novelist Ginés Pérez de Hita, who portrayed Boabdil as a vengeful and petulant tyrant. -

The Anatomy of the Arabic Script

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/20022 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Chahine, Nadine Title: Reading Arabic : legibility studies for the Arabic script Date: 2012-10-25 Chapter 2 The Anatomy of the Arabic Script What do Arabic letterforms look like? What is constant and what is changing? The development of Arabic letterforms has been varied and rich, with many differ ent styles and an abundance of regional variation. These styles form the basis for the collective visual memory of Arabs today. Some styles have gone out of use and as such are less familiar to contemporary readers. Others form the backbone of the text styles that Arabs are reading in today. What kind of letterforms do Arabs see in public communication today? There are handwritten shop signs, invitations, street banners, and such forms of short occa sional texts. These are usually penned by skilled calligraphers. Everything else is Arabic letters in their typographic form, either printed or on screen. This chapter will focus on the handwritten forms used in long texts and their transition into typographic ones. The aim is to examine the anatomy of Arabic letterforms and to dissect them into their essential parts. Why? Type designer Suzana Licko has said: people read best what they read most. The role of familiarity is crucial, and so we need to study and analyze what the readers are used to in reading. The Aesthetics of Arabic Texts: Manuscript Traditions This section focuses on three calligraphic styles that were used primarily for long texts. -

The Blue Koran Revisited*

Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 6 (2015) 196–218 brill.com/jim The Blue Koran Revisited* Jonathan M. Bloom Boston College, Chestnut Hill, ma and Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, va [email protected] Abstract The “Blue Koran” is one of the most distinctive copies of the text, copied in 15 lines of an angular gold script on leaves of blue parchment. Leaves from the manuscript have been known to scholars since the early years of the 20th century, but it first came to wide scholarly attention in the 1970s, following the publication of several leaves in such international exhibitions as the Arts of Islam at the Hayward Gallery in London. It was attributed either to ninth-century Iran or Tunisia, where the bulk of the manuscript was said to remain. The present author published several articles on the manuscript, recon- structing it as a set of seven volumes and attributing it on the basis of its abjad num- bering system as well as historical evidence to tenth-century Tunisia under Fatimid patronage. In the following decades other scholars have challenged this attribution, suggesting that the manuscript could have been produced in Umayyad Spain, Kalbid Sicily, or even Abbasid Iraq. Considering the additional pages from this manuscript that have come to light in the past decades as well as the significant advances made in the study of Koranic paleography and codicology, it is time to reexamine what is known about the manuscript and see which attribution makes the most sense. Keywords Koran (Qurʾan) – manuscripts – calligraphy – Kufic – gold – indigo – Tunisia – Fatimids The so-called “Blue Koran” is one of the rare Islamic manuscripts that is imme- diately recognizable to all viewers, even those without any knowledge of Arabic * Received October 4, 2013; accepted for publication December 11, 2013. -

Palermo Gathering Shows Libya Matters, Settlement Prospects

UK £2 Issue 182, Year 4 November 18, 2018 EU €2.50 www.thearabweekly.com Iran in Muslim Abu Dhabi’s survival soldiers in oil ambitions mode World War I Pages 15,19 Page 6 Page 18 Palermo gathering shows Libya matters, settlement prospects remain uncertain ► Both Italy and France appear to realise that their spat did them no favours internationally and seriously damaged their credibility in Libyan eyes. Michel Cousins ously damaged their credibility in Libyan eyes. As the key Europeans at the conference, both seem willing Palermo to leave the Libya file in the hands of UN Envoy for Libya Ghassan Salame. he presence of top officials Palermo was no game changer, from 30 countries in a confer- though. There was no ground-break- ence about the Libyan crisis ing initiative that could move Libya T indicates that Libya matters on an assured road to peace but Sala- for many nations, especially key Eu- me claimed it had been a success. ropean ones and the neighbouring “Palermo will be remembered as a Arab region. milestone,” he said, “to bring back Among those who attended were peace, security and prosperity to the the presidents of Egypt, Tunisia, Ni- Libyan people.” ger and Switzerland, the vice-presi- The Italians went out of their way dent of Turkey, the prime ministers to accommodate Libyan Field-Mar- of Algeria, Malta and Greece, the shal Khalifa Haftar, showing that European Union’s council president they saw his role as crucial in the Lib- and its foreign policy head, foreign yan crisis. They organised a special ministers from France, Morocco, meeting on the sidelines of the con- Chad and Qatar and officials from 18 ference so Haftar did not have to at- other countries. -

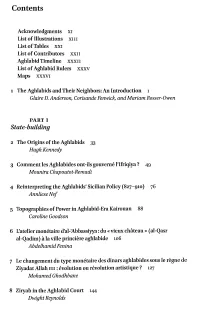

Contents Acknowledgments Xi List of Illustrations Xi 11 List of Tables Xxi

Contents Acknowledgments xi List of Illustrations xi 11 List of Tables xxi List of Contributors xxii Aghlabid Timeline xxxn List of Aghlabid Rulers xxxv Maps xxxvi 1 The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: An Introduction 1 Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Femvick, and Mariam Rosser-Owen PART 1 State-building 2 The Origins of the Aghlabids 33 Hugh Kennedy 3 Comment les Aghlabides ont-ils gouveme l'lfriqiya ? 49 Mounira Chapoutot-Remadi 4 Reinterpreting the Aghlabids' Sicilian Policy (827-910) 76 AnnlieseNef 5 Topographies of Power in Aghlabid-Era Kairouan 88 Caroline Goodson 6 L'atelier monetaire d'al-Ahhassiyya: du « vieux chateau »(al-Qasr al-Qadim) a la ville princiere aghlabide 106 Abdelhamid Fenina 7 Le changement du type monetaire des dinars aghlabides sous le regne de Ziyadat Allah 111: evolution on revolution artistique ? 127 Mohamed Ghodhbane 8 Ziryab in the Aghlabid Court 144 Dwight Reynolds PART 2 Monuments: The Physical Construction of Power 9 La Grande Mosquee de Kairouan: textes et contexte archeologique 163 Faouzi Mahfoudh 10 The Marble Panels in the Mihrab of the Great Mosque of Kairouan 190 Jonathan M. Bloom n Fragments d'histoire du minbar de Kairouan 207 Nadege Picotin and Claire Delery 12 Les carreaux verts et jaunes « caches » du mihrab de la Grande Mosquee de Kairouan et analogie avec une selection d'objets kairouanais 228 Khadija Hamdi 13 La Grande Mosquee Zitouna: un authentique monument aghlabide (milieu du ixe siecle) 248 Abdelaziz Daoulatil 14 The Zaytuna: The Mosque of a Rebellious City 269 SihemLamine 15 Le couhque -

Roads to Paradise: the Art of the Illumination of the Qur'an

Roads to Paradise: The Art of Illumination of the Quran Tajammul Hussain “Paradise lies at the feet of the mothers”1 I dedicate this chapter to the memory of my late mother This chapter is concerned with how the roads to paradise were depicted in the illumination of the Quran. It aims at providing information on some of the concepts utilized by artists through the centuries in their visual expressions of paradise and the seven heavens – which are ultimately the goal of all believers. As is the case in Sacred Art, the artist illuminator would approach his subject as entering in prayer, particularly when handling and illuminating a sacred text. Not only was he cleansing his soul but also preparing it for paradise. Through the visual rendering of this sacred text, the artist illuminator is also inviting the viewer to meditate and reflect on his own mortality and the after-life; engaging him with the rituals associated with the opening of the Quran and the reading the text thereafter. Quran manuscripts played a vital part in the rituals involving the recitation of the holy text. There is considerable evidence that Quran manuscripts were displayed regularly in the mosques or khānqahs on special stands known as kursīs — particularly, on Thursday evening, the laylat l-jumʿa,2 and on Friday before and after the congregational prayers. Admired by night under the magical candlelight or during the day under natural light, the richly illuminated frontispieces of the displayed Qurans would shine like jewels, gold and blue, and the effect would collectively lift up the spirits of the congregation and inspire the believers to enter the doorway to paradise — the real purpose of the illumination of the Quran manuscripts.