Twice Migration and Indo-Caribbean American Identity Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflecting on Caregiving

Our Immigrant Fathers: Reflecting on Caregiving Laurens Van Sluytman and Halaevalu Vakalahi Abstract: This article explores the experiences of two immigrant fathers. One is from Guyana, geographically in South America, but culturally in the Caribbean. One is from the Pacific, of Tongan ancestry but living in Hawai’i. Each father is an older adult with a chronic condition, who has been primarily cared for by their spouses. The story is told from the perspective of their two social work educator children, one male and one female, who provided support from a distance. Explored in this reflection are the complexities in the intersection of traditional cultural expectations, immigrant experience and cultural duality, and sustaining forces for the spousal caregivers and children who are social work professionals. Practice would benefit from tools that initiate narratives providing deeper awareness of environment and embeddedness within communities, both communities of origin and new communities and the implications for caregiving. Treatment planning must be inclusive of caregiving (shared with all parties) for older adults while striving to keep the family informed and respecting the resilience and lives deeply rooted in a higher. Keywords: caregiving, immigration, cultural duality, community-based writing, autoethnography, cultural context Many scholars of diverse communities tie their scholarship to their communities of origin and those communities’ relationship to larger social structures. At times, these scholars find their research interests deeply intertwined in their personal biographies. In these cases, community-based writing offers an opportunity to add deeper rich context to the lives of communities being studied or with whom professionals seek to intervene. -

The Conceptions and Practices of Motherhood Among Indo- Caribbean Immigrant Mothers in the United States: a Qualitative Study

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 12-2013 The Conceptions and Practices of Motherhood among Indo- Caribbean immigrant mothers in the United States: A Qualitative Study Darshini T. Roopnarine Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Roopnarine, Darshini T., "The Conceptions and Practices of Motherhood among Indo-Caribbean immigrant mothers in the United States: A Qualitative Study" (2013). Dissertations - ALL. 8. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/8 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This qualitative study examines multiple facets of motherhood among thirty Indo- Caribbean immigrant mothers living in Queens and Schenectady, New York, in the United States. These women belong to a growing Indo-Caribbean population that immigrated over the last forty years to the U.S. Indo-Caribbean families share a unique historical and cultural footprint that combines experiences, traditions, and practices from three distinct locations: India, Caribbean nations, and the United States. Despite the complex socio-cultural tapestry of this group, currently, little information is available about this group, including a lack of research on motherhood. Using the tenets of Social Feminism Perspectives, Gender Identity, and the Cultural-Ecological Framework, Indo-Caribbean immigrant mothers were interviewed using open-ended questions concerning their conceptions and practices of motherhood and the socio- cultural values influencing their schemas about motherhood within the context of life in the U.S. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

Guyanese Creole Features

Information Sheet on Guyanese Creole (GC) Guyanese Creole, also known as Creolese, is the language variation spoken by the nearly 780, 000 inhabitants of the country of Guyana, in South America. It is also spoken by the over 275,000 Guyanese who reside in the United States. The majority of US-based Guyanese live in the northeastern portion of the country. According to the latest U.S. Census fact finder, close to 150,000 Guyanese-Americans reside in New York city—making them New York’s fifth-largest foreign-born population. However, both in Guyana and abroad, Standard Guyanese English is considered the official language and is used in most formal and educational settings. (See US Census Quick Facts, 2019). Frequently-used GC Features Examples 1. Overgeneralization of regular past or PP When he waked up… He standed up. 2. Use of unmarked form of verb (e.g. look, run) -- Zero regular past He look (for ‘he looked’) --Zero irregular past He run (for ‘he ran’) --Zero -ing He look (for ‘he’s looking’) --Zero 3rd person singular He run (for ‘he runs everyday’) 3. Zero use of indefinite article “an” before a vowel. He see a ant. 4. Zero use of definite and/or indefinite articles in …..with other frog specific contexts. 5. Zero possessive marker,(i.e. possessor and … the bee nest possessed are juxtaposed) 6. Zero pre-verbal markers (auxiliaries—is, are) And the bees still chasing the boy. 7. Use of pre-verbal marker /bIn/ The dog been running. 8. Alternative subject constructions And when is morning… 9. -

New Cambridge History of the English Language

New Cambridge History of the English Language Volume V: English in North America and the Caribbean Editors: Natalie Schilling (Georgetown), Derek Denis (Toronto), Raymond Hickey (Essen) I The United States 1. Language change and the history of American English (Walt Wolfram) 2. The dialectology of Anglo-American English (Natalie Schilling) 3. The roots and development of New England English (James N. Stanford) 4. The history of the Midland-Northern boundary (Matthew J. Gordon) 5. The spread of English westwards (Valerie Fridland and Tyler Kendall) 6. American English in the city (Barbara Johnstone) 7. English in the southern United States (Becky Childs and Paul E. Reed) 8. Contact forms of American English (Cristopher Font-Santiago and Joseph Salmons) African American English 9. The roots of African American English (Tracey L. Weldon) 10. The Great Migration and regional variation in the speech of African Americans (Charlie Farrington) 11. Urban African American English (Nicole Holliday) 12. A longitudinal panel survey of African American English (Patricia Cukor-Avila) Latinx English 13. Puerto Rican English in Puerto Rico and in the continental United States (Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo) 14. The English of Americans of Mexican and Central American heritage (Erik R. Thomas) II Canada 15. Anglophone settlement and the creation of Canadian English (Charles Boberg) NewCHEL Vol 5: English in North America and the Caribbean Page 2 of 2 16. The open-class lexis of Canadian English: History, structure, and social correlations (Stefan Dollinger) 17. Ontario English: Loyalists and beyond (Derek Denis, Bridget Jankowski and Sali A. Tagliamonte) 18. The Prairies and the West of Canada (Alex D’Arcy and Nicole Rosen) 19. -

Peoples of African, Arab, Asian, Latino, and Native American Descent

Jorge L. Chinea’s Professional Record WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Professional Record Faculty NAME: Jorge L. Chinea DATE PREPARED: 10-17-2000 DATE REVISED: 2/13/17 OFFICE ADDRESS: 3327 F/AB HOME ADDRESS: Private OFFICE PHONE: (313) 577-4378 HOME PHONE: Private _____________________________________________________________________________ DEPARTMENT/COLLEGE: Urban, Labor and Metropolitan Affairs (1996-2005); Liberal Arts & Sciences (2005-present) PRESENT RANK & DATE OF RANK: Associate Professor, 2003 WSU APPOINTMENT HISTORY: Year Appointed/Rank: 1996, Assistant Professor Year Awarded Tenure: 2003 Year Promoted to Associate Professor: 2003 Year Promoted to Full Professor: ______________________________________________________________________________ CITIZEN OF: USA ______________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION: Baccalaureate: Suny-Binghamton, Binghamton, NY, 1980 Graduate: M.A., Suny-Binghamton, Binghamton, NY, 1983 Ph.D, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, 1994 Postgraduate (postdoctoral seminars/institutes): Harvard University, Boston, MA. International Seminar on the History of the Atlantic World: Caribbean Resources for Atlantic History, led by Dr. Bernard Bailyn, November 6-7, 1999. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, Slavery and the Atlantic Plantation Complex: 1450- 1890, led by Dr. Philip D. Curtin, Summer 1995. University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. Global Change—the USA: African American and Latino History and Culture Since 1960, June 25-29, 1992. ______________________________________________________________________ -

Asian Modeawards at the Reception, When People Section Hope to Mingle with Colleagues and Friends

share significant overlap in members. It is Spring / Summer From the too time consuming to hand out all 2014 Asian Modeawards at the reception, when people Section hope to mingle with colleagues and friends. I’m also happy to note that our Inside this Issue Chair reception is co-sponsored by the journal Ethnic and Racial Studies and Routledge. From the Section Chair It is with great pleasure that I share the latest information about our section and Routledge will be running a small 1 critical updates, including section sessions competition during the joint reception on Your Section Officers at the upcoming ASA conference in San August 18. Reception attendees may drop 2 Francisco, a new mentoring session at the their email addresses into a tombola for a conference, a co-hosted reception, and chance to win a Routledge book (choice 2014 Section newly-elected officers. from books available at the Routledge 2 Election Results stand). These email addresses will be used Our Section day is Monday, August 18. to encourage members to sign up for 2014 Section This year in particular it promises to be a email table-of-contents alerts for Ethnic Award Winners 2 full, dynamic day. In line with the and Racial Studies and Identities. conference theme, we will have two Section Activities at the In addition to all this, our section is 2014 ASA Meeting in section panels: Work, Labor and 4 excited to host a mentoring session on San Francisco Inequality in Asia, and Work Labor and August 18th as well. At last year’s Selected Opportunities Inequality in Asian America. -

Indo-Caribbeans in New York City" (2008)

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 5-18-2008 Immigration and Women's Empowerment: Indo- Caribbeans in New York City Farah Persaud Pace University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Recommended Citation Persaud, Farah, "Immigration and Women's Empowerment: Indo-Caribbeans in New York City" (2008). Honors College Theses. Paper 77. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/77 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Immigration and Women’s Empowerment: Indo-Caribbeans in New York City Farah Persaud [email protected] Graduation Date: May 2008 Major: Information Systems Advisor: Aseel Sawalha, PhD Department: Sociology/Anthropology; Women’s and Gender Studies Advisor’s Signature: ____________________________________________________ TO THE PACE UNIVERSITY PFORZHEIMER HONORS COLLEGE: Immigration and Women’s Empowerment: Indo-Caribbeans in New York City As thesis advisor for _____Farah Persaud_____ , I have read this paper and find it satisfactory. _________________________________________ Aseel Sawalha, PhD (Thesis Advisor ) __________________ Date 2 Immigration and Women’s Empowerment: Indo-Caribbeans in New York City Precís Research Question How do Indo-Caribbean women perceive their socio-economic statuses since migrating to New York City? Context of the Problem Since the signing of the U.S. Immigration Act of 1965, there has been a massive influx of West Indian immigrants in New York City. Today, the West Indian subpopulation has grown to be among the largest minority groups in New York City. -

11809 Hon. Major R. Owens Hon. Carolyn B. Maloney

June 25, 2001 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 11809 Mr. Speaker, I was unavoidably detained for come a household name to the Guyanese CSD 30 has created an interactive learning Rollcall No. 181, on agreeing to the amend- family. From a one-desk, one-phone and one- community employing the teachers, parents, ment to prevent use of funds to execute a final staff agency, National Pride is now one of the students, and local universities of Queens, lease agreement for oil or gas development in most successful enterprises in New York and New York, and its mission would greatly be the area of the Gulf of Mexico known as Guyana. Nigel Pile has expanded this oper- supported by additional funding. Lease Sale 181 prior to April 1, 2002. Had I ation to two offices in New York and five in I join with my dear friend from New York, in been present I would have voted ‘‘no.’’ Guyana. Through this expansion, he has cre- that it is my hope that this body will find the Mr. Speaker, I was unavoidably detained for ated opportunities of entrepreneurship and additional 25 million dollars for the Magnet Rollcall No. 182, on agreeing to the amend- employment for the residents of the Flatbush School Assistance Program at the U.S. De- ment to require that none of the funds in the and Queens communities. The establishment partment of Education as this bill works its bill may be used to suspend or revise the final of National Pride has created channels way through the process. regulations published in the Federal Register through which Guyanese Americans can ini- f on November 21, 2000, that amended envi- tiate and maintain contact with relatives and ronmental mining rules. -

Informational Materials

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 06/21/2020 4:04:27 FM JJ&B Acct no.: 201443 Registration no.: 6809 The attached op~ed was distributed to the following persons by JJ&B on behalf of the APNU+AFC Coalition: Contact Office Date Alex Brockwehl Western Hemisphere Subcomm. June 19, 2020 U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee Katherine Dueholm Office of Caribbean Affairs June 19, 2020 U.S. Dept, of State Viviana Bono Office of Sen. Marco Rubio June 19, 2020 Carlos Trujillo U.S. Ambassador to OAS June 19, 2020 Matthew Pottinger Deputy National Security Advisor June 19, 2020 Mary Anastasia O'Grady Wall Street Journal June 19, 2020 Richard Rahn Washington Times June 19, 2020 Received hv NSD/FARA Registration Unit 06/21/2020 4:04:27 PM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 06/21/2020 4:04:27 FM 6/10/2020 Guyana election battle matters to the U$ Guyana election battle matters to the US by Bart S. Fisher | June 19, 2020 01:17 PM A contested election held on March 2 in the South American nation of Guyana may be more important to the United States than meets the eye. At stake for the people of Guyana is the long-awaited prosperity that could come from its newly acquired status as a major oil- producing nation. At stake for the U.S. is having a stable ally in an unstable part of the world. The current government is controlled by the APNU + AFC Coalition, which sought a second term following a 2015 victory over the opposition left-wing People's Progressive Party. -

6-SA16 Wilkinson

Haciendo Patria: The Puerto Rican Flag in the Art of Juan Sánchez Michelle Joan Wilkinson uerto Rico is an island adrift in the predominantly postcolonial Caribbean sphere that is its topographic equivalent. Lying between the North Americas and the Nuestras Américas, Puerto Rico epitomizes the historical reality of a “divided nation”: nearly Pone-half of the Puerto Rican population lives on the US mainland.¹ Some scholars have used the phrases “commuter nation” and “translocal nation” to illuminate the transit of bodies on fl ights between San Juan and cities such as New York, Miami, and Chicago.² Th ese terms—divided nation, commuter nation, translocal nation—affi x paradigms of nationality, albeit a transitory nationality, onto the people of this nonsovereign nation. Puerto Rican nationality is thus rendered vis-à-vis the dynamics of Puerto Rican migra- tion and, specifi cally, migration to the US mainland. As such, Puerto Rican nationality and nationalism operate in relational modes that emphasize the self-positioning and 1. On “the divided nation” see Kal Wagenheim and Olga Jímenez de Wagenheim, eds., Th e Puerto Ricans: A Documentary History (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1994), 283. 2. On “the commuter nation” see Carlos Antonio Torre, Hugo Rodríguez-Vecchini, and William Burgos, eds. Th e Commuter Nation: Perspectives on Puerto Rican Migration (Río Piedras: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1994). On “translocal nation” see Mayra Santos-Febre quoted in Agustín Lao-Montes, “Islands at the Crossroads: Puerto Ricanness Travelling between the Translocal Nation and the Global City,” in Puerto Rican Jam: Rethinking Colonialism and Nationalism, ed. -

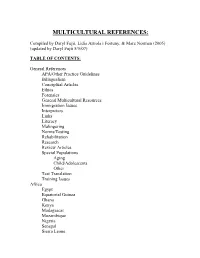

Multicultural References

MULTICULTURAL REFERENCES: Compiled by Daryl Fujii, Lidia Artiola i Fortuny, & Marc Norman (2005) (updated by Daryl Fujii 5/5/07) TABLE OF CONTENTS: General References APA/Other Practice Guidelines Bilingualism Conceptual Articles Ethics Forensics General Multicultural Resources Immigration Issues Interpreters Links Literacy Malingering Norms/Testing Rehabilitation Research Review Articles Special Populations Aging Child/Adolescents Other Test Translation Training Issues Africa Egypt Equatorial Guinea Ghana Kenya Madagascar Mozambique Nigeria Senegal Sierra Leone South Africa Sudan Tanzania Uganda Zaire Zambia Zimbabwe African Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Caribbean and Latin America Asian Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Bangla Deshi Chinese Filipino Guamanian-Chamorro Indian Indonesian Japanese Korean Laotian Malaysian Pakistani Singaporean Thai Vietnamese Americans of European Origin General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Austria Belgium Bosnia Bulgaria Croatia Czechoslovakia Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Great Britain Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy Latvia Lithuania Macedonia Malta Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Romania Russia Serbia Slovakia Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland Turkey Ukraine Australian/New Zealand Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transsexual Hispanic/Latino Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review Norms/Testing Argentina Brazil Chile Columbia Ecuador Mexico Peru Puerto Rico Venezuela Middle Eastern Americans General Cultural Conceptual Review