Le Corbusier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Maison La Roche Construite Entre 1923 Et 1925 Par Le Corbusier Et Pierre Jeanneret, La Maison La Roche Constitue Un Projet Architectural Singulier

Dossier enseignant Maison La Roche – Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret. Photo Olivier Martin Gambier La Maison La Roche Construite entre 1923 et 1925 par Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret, la Maison La Roche constitue un projet architectural singulier. En effet, l’originalité de cette maison est de réunir une galerie de tableaux et les appartements du propriétaire et collectionneur : Raoul La Roche. La Maison La Roche est située au fond de l’impasse du Docteur Blanche dans le 16ème arrondissement de Paris, dans un quartier qui, à cette époque est en cours d’aménagement. L’utilisation de matériaux de construction nouveaux tels que le béton armé permet à Le Corbusier de mettre en œuvre ce qu’il nommera en 1927, les «Cinq points d’une architecture nouvelle». Il s’agit de la façade libre, du plan libre, des fenêtres en longueur, du toit-jardin, et des pilotis. La Maison La Roche représente un témoignage emblématique du Mouvement Moderne, précédant celui de la Villa Savoye (1928) à Poissy. De 1925 à 1933 de nombreux architectes, écrivains, artistes, et collectionneurs viennent visiter cette maison expérimentale, laissant trace de leur passage en signant le livre d’or disposé dans le hall. La Maison La Roche ainsi que la Maison Jeanneret mitoyenne ont été classées Monuments Historiques en 1996. Elles ont fait l’objet de plusieurs campagnes de restauration à partir de 1970. Maison La Roche 1 Le propriétaire et l’architecte THĖMES Le commanditaire : Le rôle de l’architecte Raoul La Roche (1889-1965) d’origine bâloise, (bâtir, aménager l’espace) s’installe à Paris en 1912 pour travailler au Crédit La commande en Commercial de France. -

La Maison La Roche Construite Entre 1923 Et 1925 Par Le Corbusier Et Pierre Jeanneret, La Maison La Roche Constitue Un Projet Architectural Singulier

Dossier enseignant Maison La Roche – Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret. Photo Olivier Martin Gambier La Maison La Roche Construite entre 1923 et 1925 par Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret, la Maison La Roche constitue un projet architectural singulier. En effet, l’originalité de cette maison est de réunir une galerie de tableaux et les appartements du propriétaire et collectionneur : Raoul La Roche. La Maison La Roche est située au fond de l’impasse du Docteur Blanche dans le 16ème arrondissement de Paris, dans un quartier qui, à cette époque est en cours d’aménagement. L’utilisation de matériaux de construction nouveaux tels que le béton armé permet à Le Corbusier de mettre en œuvre ce qu’il nommera en 1927, les «Cinq points d’une architecture nouvelle». Il s’agit de la façade libre, du plan libre, des fenêtres en longueur, du toit-jardin, et des pilotis. La Maison La Roche représente un témoignage emblématique du Mouvement Moderne, précédant celui de la Villa Savoye (1928) à Poissy. De 1925 à 1933 de nombreux architectes, écrivains, artistes, et collectionneurs viennent visiter cette maison expérimentale, laissant trace de leur passage en signant le livre d’or disposé dans le hall. La Maison La Roche ainsi que la Maison Jeanneret mitoyenne ont été classées Monuments Historiques en 1996. Elles ont fait l’objet de plusieurs campagnes de restauration à partir de 1970. Maison La Roche 1 Le propriétaire et l’architecte THĖMES Le commanditaire : Le rôle de l’architecte Raoul La Roche (1889-1965) d’origine bâloise, (bâtir, aménager l’espace) s’installe à Paris en 1912 pour travailler au Crédit La commande en Commercial de France. -

Charlotte Perriand

Charlotte Perriand Ce dossier thématique est proposé par le groupe Ressources, compétences, pratiques pédagogiques auprès des jeunes du pôle Sensibilisation de la Fédération nationale des Conseils d’Architecture, d’Urbanisme et de l’Environnement grâce au concours de l’IFÉ et au soutien du Ministère de la Culture et de la communication. Sommaire : - Charlotte Perriand Dossier pédagogique de l’exposition Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) organisée par le Centre Pompidou en 2006. - Contribution des CAUE à Histoire des arts - Contribution des CAUE au programme de Technologie CHARLOTTE PERRIAND http://www.centrepompidou.fr/education/ressources/ENS-perr... Dossier pédagogique - Parcours Exposition CHARLOTTE PERRIAND DU 7 DÉCEMBRE 2005 AU 27 MARS 2006 Charlotte Perriand, 1974. Photographie Pernette Perriand-Barsac et Jacques Barsac/AChP © AChP 2005 INTRODUCTION LE MOBILIER MÉTALLIQUE ET L'ESPRIT MODERNE Les débuts d'une carrière LE LOGEMENT MINIMUM Les théories novatrices des CIAM L'ENGAGEMENT POLITIQUE Le rôle des intellectuels et des artistes à partir de 1930 L'ART BRUT La recherche d'une création naturelle 1 sur 22 04/05/11 10:00 CHARLOTTE PERRIAND http://www.centrepompidou.fr/education/ressources/ENS-perr... LE JAPON Un écho aux théories corbuséennes L'ÉQUIPEMENT COLLECTIF Les maisons d'étudiants à Paris L'ART D'HABITER Créer pour tous LE BRÉSIL Nouvelles formes et nouveaux matériaux LA PASSION DE LA MONTAGNE Privilégier la relation intérieur-extérieur LA MAISON DE THÉ Entre tradition et modernité BIBLIOGRAPHIE INTRODUCTION Cette exposition rétrospective présente une étude approfondie du travail de Charlotte Perriand, artiste majeure du 20e siècle. Dans un parcours chronologique, à travers la reconstitution de nombreux espaces, elle met en valeur tant l'architecte que la designer d'un mobilier original. -

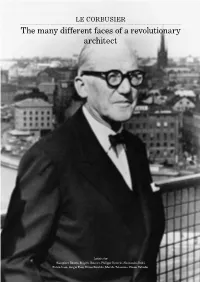

Le Corbusier

LE CORBUSIER ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... IThe mille many volti different di un architetto faces of a rivoluzionario revolutionary architect Articles by Giampiero Bosoni, Brigitte Bouvier, Philippe Daverio, Alessandra Dolci, Fulvio Irace, Sergio Pace, Bruno Reichlin, Marida Talamona, Simon Zehnder The many different faces of a revolutionary architect ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Introduction “Le Corbusier changed architecture – and the architect”: this glowing tribute from André Malraux to Le Corbusier is as relevant now as it was then. Born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, Le Corbusier (1887-1965) was the most inventive and influential architect of the 20th century. An architect, furniture designer, painter, sculptor, theoretician and poet all rolled into one, he designed 75 buildings in 11 countries, devised 42 urban development projects and wrote books. He left behind 8,000 drawings and over 500 paintings, sculptures and tapestries. Designed and constructed between the early 1920s, when the modern movement was in its infancy, and the 1960s, when this avant-garde architecture took hold, Le Corbusier’s buildings mark a clean break with the styles, technologies and practices of -

Le Corbusier: Furniture and the Interior Charlotte Benton Journal Of

Le Corbusier: Furniture and the Interior Charlotte Benton Journal of Design History, Vol. 3, No. 2/3. (1990), pp. 103-124. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0952-4649%281990%293%3A2%2F3%3C103%3ALCFATI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-F Journal of Design History is currently published by Oxford University Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oup.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is an independent not-for-profit organization dedicated to and preserving a digital archive of scholarly journals. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Fri Apr 27 22:34:44 2007 Charlotte Benton Le Corbusier: Furniture and the Interior Introduction Almost every important inspiration [in furniture design] comes from architects.' While it is probably true that trained designers like that the heart of architectural composition was the Gerrit Rietveld, Marcel Breuer, or Adolf Schneck2 interior. -

Lucien Hervã© Photographs of Architecture And

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c87086jc Online items available Finding Aid for the Lucien Hervé photographs of architecture and artworks by Le Corbusier Talia Olshefsky Finding Aid for the Lucien Hervé 2002.R.41 1 photographs of architecture and artworks by Le Corbusier ... Descriptive Summary Title: Lucien Hervé photographs of architecture and artworks by Le Corbusier Date (inclusive): 1949-1965 Number: 2002.R.41 Creator/Collector: Hervé, Lucien Physical Description: 12.6 linear feet(42 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The collection contains over 18,000 photographic negatives, 1,700 color slides, and 1,200 transparencies taken by Lucien Hervé, Le Corbusier's official photographer. Organized by project, this photographic material includes both Hervé's original negatives and copys negatives from the work of other photographers who have documented Le Corbusier's architectural projects. Subjects include Le Corbusier's executed buildings, unrealized architectural designs, and non-architectural works, such as paintings, tapestries, and sculptures. The collection also contains hundreds of portraits of Le Corbusier, both formal and informal. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English, with some French. Biographical / Historical One of the most prominent architectural photographers of the twentieth century, Lucien Hervé created a body of work, inspired by a Modernist philosophy, that remains uniquely identifiable. -

TRILOGIE LE CORBUSIER 3 © FLC - Prolitteris © FLC - Prolitteris 5 the Le Corbusier Trilogy

DOWNLOAD PICTURES AND TEXTS ON: TRILOGIE LE CORBUSIER © FLC - ProLitteris © FLC - ProLitteris 3 5 THE LE CORBUSIER TRILOGY “You employ stone, wood and concrete, and with these materials you build houses and palaces : That is construction. Ingenuity is at work. But suddenly you touch my heart, you do me good. I am happy and I say : ‘This is beautiful.’ That is architecture. Art enters in.” Vers une architecture, Le Corbusier, ed. G. Crès, 1923 High in the Jura Mountains of Switzerland, a few kilometers east of France, is perched the small town of La Chaux-de-Fonds — for centuries the wellspring of an almost divine congruence of genius. Among those born here : Le Corbusier (born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret), one of the greatest names in modern architecture and design; pioneering automaker Louis Chevrolet; and poet/novelist Blaise Cendrars. The aesthetic movement L’Art nouveau was refined in La Chaux-de-Fonds — as the old village gave way to a modern city beginning of the 20th century, a regional Art nouveau variant, the “Style Sapin”, emerged here, exclusive to the burgeoning industrial watchmaking centre. And the grace of its architecture and ingenuity of its urban plan have led to its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site. 6 7 The genius inherent to La Chaux-de-Fonds is today best exemplified by the watchmakers of Girard-Perregaux, who - in cooperation with Foundation Le Corbusier - are employing gold, sapphire crystal, steel and even concrete to reinterpret the work of the great Modernist in a series of exceptional new timepieces. This sublime project is the apotheosis of more than a century of communal history between the Jeanneret and Girard-Perregaux families. -

Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier AUK College of Art & Sciences/ID IND311 Interior Design History II Asst. Prof. Siniša Prvanov Spring 2019 Page 1 of 98 Contents: Introduction 1. Villa Savoye (1928–1931) 2. World War II and Reconstruction; Unité d'Habitation in Marseille (1939–1952) 3. Villa Shodhan (1951-1956) 4. Le Corbusier and an Analysis of Form 5. Furniture Design Page 2 of 98 INTRODUCTION Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (1887-1965), known as Le Corbusier, was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now called modern architecture. He was born in Switzerland and became a French citizen in 1930. His career spanned five decades, and he designed buildings in Europe, Japan, India, and North and South America. Dedicated to providing better living conditions for the residents of crowded cities, Le Corbusier was influential in urban planning, and was a founding member of the Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). Le Corbusier prepared the master plan for the city of Chandigarh in India, and contributed specific designs for several buildings there. Like his contemporaries Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier did not have formal academic training as an architect. He was attracted to the visual arts and at the age of fifteen he entered the municipal art school in La-Chaux-de-Fonds which taught the applied arts connected with watchmaking. Three years later he attended the higher course of decoration, founded by the painter Charles L'Eplattenier, who had studied in Budapest and Paris. But in further years he moved into architecture very fast. -

Le Corbusier 2002.R.41

Lucien Hervé photographs of architecture and artworks by Le Corbusier 2002.R.41 Descriptive and chronological list of buildings and projects covered by the archive: Name and date of project, as given Name as given in “Contents List” Hervé’s original dossier in the indicated volume of Œuvre (original inventory of Hervé’s dossiers numbers. complète unless otherwise noted, (binders) of negatives and Entries in italics are for or enclosed in square brackets transparencies) binders of color transparencies Villa Fallet (in catalog for 1987 Villa Favrod ou Fallet (VF) Dossier 10 exhibition, Le Corbusier, Architect of Dossier C5 the Century), 1905-1907 Villa Stotzer (in catalog for 1987 Villa Stotzer Dossier C5 exhibition, La Chaux-de-Fonds et Jeanneret avant Le Corbusier), 1909 Villa Jaquemet (in catalog for 1987 Villa Jacot Dossier C5 exhibition, La Chaux-de-Fonds et Jeanneret avant Le Corbusier), 1909 Ateliers d’artistes, 1910. Vol. 1 Atelier d’artistes Dossier 19 Villa Favre-Jacot, 1912 (in catalog Villa Fèvre-Jaquet (VFJ) Dossier 10 for 1987 exhibition, La Chaux-de- Dossier C5 Fonds et Jeanneret avant Le Corbusier) Villa Jeanneret (in catalog for 1987 Villa Jeanneret (VJEA) Dossier 10 exhibition, La Chaux-de-Fonds et Dossier C5 Jeanneret avant Le Corbusier), 1912 Maison “Dom-ino,” 1914-1915. Vol. Maison Domino Dossier 19 1 Dossier C7 Villa Schwob (in catalog for 1987 Villa Schwob (VLCF) Dossier 10 exhibition, Le Corbusier, Architect of Dossier C4 the Century), 1916-17 Troyes, 1919. Vol. 1 Troyes Dossier 10 Maison “Monol,” 1920. Vol. 1 Not in original inventory Maison “Citrohan,” 1920. Vol. -

De Man Stierf in Zijn Zwembroek Vijftig Jaar Geleden. Maar Dat Is Een

Le Corbusier, vijftig jaar dood maar nog altijd essentieel De man stierf in zijn zwembroek vijftig jaar geleden. Maar dat is een voetnoot in het rijk gevulde leven van Le Corbusier. Verguisd door fans van fermettes, met een troebel oorlogsverleden, en nog altijd relevant. tekst Jesse Brouns SMETTELOZE e e g g a a t t r r o o p p e e R R HUIZEN, TROEBEL N A I H C T I D R E U G E M . G , U O D I P M O P E R T N E C © 7 3 9 1 . A C , R E VERLEDEN I S U B R O C E L , ̧ C R D N A I G O R DeMorgen. magazine 2 mei 2015 32 — 33 Le Corbusier, vijftig jaar dood maar nog altijd essentieel ver vooruit. Misschien zaait hij daarom nog altijd twee - Het radicale modernisme van Le Corbusier en dracht, ook 50 jaar na zijn dood. Jeanneret was niet feilloos. Pierre en Eugénie Savoye Op het wandelpad voor Maison La Roche staan elke moesten met een rechtszaak dreigen voor Le Corbusier dag enthousiaste groepjes architectuurtoeristen, met of ook maar iets ondernam tegen de waterlekken in hun witte zonder selfiesticks, bedevaartgangers in het walhalla van blokkendoos. het modernisme. In 1930 werd Le Corbusier Fransman. Datzelfde jaar Maar elders wordt Le Corbusier nog altijd heftig ver - trouwde hij met Yvonne Gallis, een model uit Monaco, foeid: voor de aanhangers van fermettes, kastelen en 8 jaar na hun eerste ontmoeting. Er was ook een stormach - andere vormen van traditionele bouwkunst, heeft de archi - tige affaire met het in bananenrokjes gehulde musicalfeno - tect het moderne appartementenblok op zijn geweten en meen Josephine Baker, die hij op een schip met bestem - dus de verwoesting van de beschaafde wereld met iedereen ming Buenos Aires had leren kennen (de danseres reisde in zijn eigen huisje en tuintje.