17 Chapter 5.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Teplate

Volume-05 ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) Issue-04 RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary April -2020 www.rrjournals.com[Peer Reviewed Journal] Analysis of reflection of the Marxist Cultural Movement (1940s) of India in Contemporary Periodicals Dr. Sreyasi Ghosh Assistant Professor and HOD of History Dept., Hiralal Mazumdar Memorial College for Women, Dakshineshwar, Kolkata- 700035 (India) ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History In this study I have tried my level best to show how the Marxist Cultural Movement ( Published Online: 16 Apr 2020 1940s) of Bengal/ India left its all-round imprint on contemporary periodicals such as Parichay, Agrani, Arani, Janayuddha, Natun Sahitya, Kranti, Sahityapatra etc. That Keywords movement was generated in the stormy backdrop of the devastating Second World Anti- Fascist, Communist Party, Marxism, War, famine, communal riots with bloodbath, and Partition of india. Undoubtedly the Progressive Literature, Social realism. Communist Party of India gave leadership in this cultural renaissance established on social realism but renowned personalities not under the umbrella of the Marxist *Corresponding Author Email: sreyasighosh[at]yahoo.com ideology also participated and contributed a lot in it which influenced contemporary literature, songs, painting, sculpture, dance movements and world of movie- making. Organisations like the All-India Progressive Writers” Association( 1936), Youth Cultural Institute ( 1940), Association of Friends of the Soviet Union (1941), Anti- Fascist Writers and Artists” Association ( 1942) and the All- India People”s Theatre Association (1943) etc emerged as pillars of that movement. I.P.T.A was nothing but a very effective arm of the Pragati Lekhak Sangha, which was created mainly for flourishing talent of artists engaged with singing and drama performances. -

A Nnual R Epo Rt 2002

CMYK Annual ReportAnnual 2002 - 2003 Annual Report 2002-2003 Department of Women and Child Development Women Department of Ministry Development of HumanResource Government ofIndia Government Department of Women and Child Development Ministry of Human Resource Development Government of India CMYK CMYK To call woman the weaker sex is a libel; it is mans injustice to woman. If by strength is meant brute strength, then, indeed, is woman less brute than man. If by strength is meant moral power, then woman is immeasurably mans superior. Has she not greater intuition, is she not more self-sacrificing, has she not greater powers of endurance, has she not greater courage? Without her man could not be. If nonviolence is the law of our being, the future is with woman. Who can make a more effective appeal to the heart than woman? Mahatma Gandhi Designed and produced by: Fountainhead Solutions (Pvt.) Ltd email: [email protected] CMYK Annual Report 2002-03 Department of Women and Child Development Ministry of Human Resource Development Government of India Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 An Overview 7 Chapter 3 Organization 17 Chapter 4 Policy and Planning 25 Chapter 5 The Girl Child in India 43 Chapter 6 Programmes for Women 73 Chapter 7 Programmes for Children 91 Chapter 8 Food and Nutrition Board 111 Chapter 9 Other Programmes 117 Chapter 10 Gender Budget Initiative 127 Chapter 11 Child Budget 143 Chapter 12 National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 153 Chapter 13 Central Social Welfare Board 163 Chapter 14 National Commission for Women 173 Chapter 15 Rashtriya Mahila Kosh 183 Annexures 189 Introduction O Lord, why have you not given woman the right to conquer her destiny? Why does she have to wait head bowed By the roadside, waiting with tired patience Hoping for a miracle in the morrow Rabindranath Tagore Introduction The Department of Women and Child Development was set up in 1985 as a part of the Ministry of Human Resource Development to give the much-needed impetus to the holistic development of women and children. -

Red Bengal's Rise and Fall

kheya bag RED BENGAL’S RISE AND FALL he ouster of West Bengal’s Communist government after 34 years in power is no less of a watershed for having been widely predicted. For more than a generation the Party had shaped the culture, economy and society of one of the most Tpopulous provinces in India—91 million strong—and won massive majorities in the state assembly in seven consecutive elections. West Bengal had also provided the bulk of the Communist Party of India– Marxist (cpm) deputies to India’s parliament, the Lok Sabha; in the mid-90s its Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, had been spoken of as the pos- sible Prime Minister of a centre-left coalition. The cpm’s fall from power also therefore suggests a change in the equation of Indian politics at the national level. But this cannot simply be read as a shift to the right. West Bengal has seen a high degree of popular mobilization against the cpm’s Beijing-style land grabs over the past decade. Though her origins lie in the state’s deeply conservative Congress Party, the challenger Mamata Banerjee based her campaign on an appeal to those dispossessed and alienated by the cpm’s breakneck capitalist-development policies, not least the party’s notoriously brutal treatment of poor peasants at Singur and Nandigram, and was herself accused by the Communists of being soft on the Maoists. The changing of the guard at Writers’ Building, the seat of the state gov- ernment in Calcutta, therefore raises a series of questions. First, why West Bengal? That is, how is it that the cpm succeeded in establishing -

SO&Ltlijamltlttr

a~r~~to~as~ra• SO<liJAMltltTr -NEWS RELEASE- REVOLUT ION IS THE MAIN TREND IN THE WORlD TODAY 9-12-72 ' ' AFRO-ASIAN SOLIDARITY News Release is produced by AFRO-ASIAN PEOPLE'S SOLIDARITY MOVEMENT. It is distributed free to members and supporters. Donations & enquiries may be sent to: AAPSM. P.O.BOX 712. LONDON SW17 2EU RED SALUTE TO THE . GREAT . INDIAN PEOPLE ' S l-IBERATION ARNY ! Statement of the Indian Progressive Study Group (England), commemorating the 2nd Anniversary of the formation of the great Indian People ' s Liberation Army , December 7 1 1972. DeccGber 7, 1972 marks the second anniversary of the formation of the great Indian Pl~CPLE'S LI:iLHATION Am,y (PLA) under tlle leadership of the great Cornr.JUnist Party of India (K-L) and the great leader and helmsman of Indian Revolution, res pected nnd beloved Comrade Charu Mazumdar . Armed struggle started in India with the clap of sprinG thunder of Naxalbari in 1967 personally led by Comrade Charu Kazumdar . Ever since then , this single sparl: hc.s created n prairie fire of the armed agrarian revolution in all l)o.rts of India, leadins to the formation of the great Communist Party of India (H-L) on April 22 1 1969 and to the Historic 8th Congress (First since tkxalbari) of the C6mmunist Party of India (M-L) in May 1970. From the platform of this historic Party Congress Comrade Charu Mazumdar said: 11 It is sure the Red Army can be created not only in Srikakulam but also in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh , Bihar ancl ·.Jest Bengal. -

Assessing the Promise and Limitations of Joint Forest Management in an Era of Globalisation: the Case of West Bengal.1

Assessing the promise and limitations of Joint Forest Management in an era of globalisation: the case of West Bengal.1 Douglas Hill, Australian National University. Introduction This paper seeks to interrogate the claims of the dominant discourses of globalisation with regard to their compatibility with mechanisms for empowering marginalised communities and providing a basis for sustainable livelihood strategies. These concerns are examined from the perspective of the development experience of India, including the New Economic Policy (NEP) regime initiated in India in 1991, and its subsequent structural transformation towards greater conformity with the imperatives of ‘economic liberalisation’. It suggests that the Indian institutional structure of development has been such that resources have been unequally distributed and that this has reinforced certain biases particularly on a caste/class and gender basis. The analysis suggests that these biases have reduced the legitimacy of previous models of resource management and continue to hamper the prospects of current formulations. These concerns are analysed utilising an examination of the management of forest-based Common Property Resources (CPRs) within the context of rural West Bengal, specifically the system of Joint Forest Management (JFM) i. Such an examination is pertinent since those communities dependent upon CPRs for a substantial part of their subsistence requirements are amongst the most vulnerable strata of society. As Agrawhal, (1999), Platteau (1999, 1997) and others have argued, these CPRs function as a “social safety net” or “fall-back position”ii. This should be seen within the broader context of rural development, since the success or failure of the total rural development environment including poverty alleviation programs, agriculture, rural credit and employment (both on and off farm), will influence the relative dependence on these CPRs. -

India's Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 22 India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency by Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Hard-line communists, belonging to the political group Naxalite, pose with bows and arrows during protest rally in eastern Indian city of Calcutta December 15, 2004. More than 5,000 Naxalites from across the country, including the Maoist Communist Centre and the Peoples War, took part in a rally to protest against the government’s economic policies (REUTERS/Jayanta Shaw) India’s Naxalite Insurgency India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency By Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. -

Of Concepts and Methods "On Postisms" and Other Essays K

Of Concepts and Methods "On Postisms" and other Essays K. Murali (Ajith) Foreign Languages Press Foreign Languages Press Collection “New Roads” #9 A collection directed by Christophe Kistler Contact – [email protected] https://foreignlanguages.press Paris, 2020 First Edition ISBN: 978-2-491182-39-7 This book is under license Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ “Communism is the riddle of history solved, and it knows itself to be this solution.” Karl Marx CONTENTS Introduction Saroj Giri From the October Revolution to the Naxalbari 1 Movement: Understanding Political Subjectivity Preface 34 On Postisms’ Concepts and Methods 36 For a Materialist Ethics 66 On the Laws of History 86 The Vanguard in the 21st Century 96 The Working of the Neo-Colonial Mind 108 If Not Reservation, Then What? 124 On the Specificities of Brahmanist Hindu Fascism 146 Some Semi-Feudal Traits of the Indian Parliamentary 160 System The Maoist Party 166 Re-Reading Marx on British India 178 The Politics of Liberation 190 Appendix In Conversation with the Journalist K. P. Sethunath 220 Introduction Introduction From the October Revolution to the Nax- albari Movement: Understanding Political Subjectivity Saroj Giri1 The first decade since the October Revolution of 1917 was an extremely fertile period in Russia. So much happened in terms of con- testing approaches and divergent paths to socialism and communism that we are yet to fully appreciate the richness, intensity and complexity of the time. In particular, what is called the Soviet revolutionary avant garde (DzigaVertov, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Boris Arvatov) was extremely active during the 1920s. -

The Nepalese Maoist Movement in Comparative Perspective: Learning from the History of Naxalism in India

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 23 Number 1 Himalaya; The Journal of the Article 8 Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 2003 The Nepalese Maoist Movement in Comparative Perspective: Learning from the History of Naxalism in India Richard Bownas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Bownas, Richard. 2003. The Nepalese Maoist Movement in Comparative Perspective: Learning from the History of Naxalism in India. HIMALAYA 23(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol23/iss1/8 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD BowNAS THE NEPALESE MAOIST MovEMENT IN CoMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE: LEARNIN G FROM THE H ISTORY OF NAXALISM IN INDIA This paper compares the contemporary Maoist movement in Nepal with the Naxalite movemelll in India, from 1967 to the present. The paper touches on three main areas: the two movemems' ambiguous relationship to ethnicity, the hi stories of prior 'traditional' m obilization that bo th move ments drew on, and the relationship between vanguard and mass movement in both cases. The first aim of the paper is to show how the Naxalite movemem has transformed itself over the last 35 years and how its military tacti cs and organizational· form have changed . I then ask whether Nepal's lvla o ists more closely resemble the earli er phase of Naxali sm , in which the leadership had broad popular appeal and worked closely with its peasant base, o r its later phase, in which the leadership became dise ngaged fr om its base and adopted urban 'terror' tactics. -

Impact of WTO-SV-Final.Pmd

I Women Fight Police during the Tebhaga Movement when the slogan was “Jan Deba, Ddhan Debo na” (we will give our lives, but will not give our rice) II Contents Foreword .............................................................................................................................................................. (vi) Preface ................................................................................................................................................................ (viii) Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. (ix) PART - I AN OVERVIEW 1.1 AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN INDIA ............................................................................................................ 3 Characteristics of Labour Market in Agriculture ..................................................................................... 5 Status of Plantation Workers................................................................................................................... 6 Laws Governing Labour Standards in Agriculture ..................................................................................6 The Plantation Labour Act, 1951 as Amended in 1981. ........................................................................ 6 Poverty and Unemployment ................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 WOMEN IN AGRICULTURE ...................................................................................................................... -

Origin and Background of Tebhaga Movement in Bengal (1946-1950)

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 7, Issue 1, Jan 2019, 389-396 © Impact Journals ORIGIN AND BACKGROUND OF TEBHAGA MOVEMENT IN BENGAL (1946-1950) Shyamal Chandra Sarkar Assistant Professor, Department of History, P.D. Women’s College, Jalpaiguri, West Bengal, India Received: 14 Jan 2019 Accepted: 24 Jan 2019 Published: 31 Jan 2019 ABSTRACT The Tebhaga Movement of 1946-1950 was an intense peasant movement in the history of India. It was a fierce peasant uprising on the eve of India’s independence and the partition of Bengal. Bengal has a history of rural resistance, throughout the whole period of colonial rule. The Tebhaga uprising in many ways was the culminating point, spreading over large areas of the countryside and expressing the urge of laboring men and women to be liberated from exploitation. Sixty lakh people participated in the Tebhaga movement at its peak. The issue around which the campaign was launched was economic. In September 1946, less than a year before the partition of Bengal by the British, the provincial Kisan Sabha (peasants’ association), which was guided by the Communist Party, decided to initiate, on an experimental basis, a struggle for two-thirds of the harvest. This work tried to focus on how the Movement was originated and what was the background behind this movement. KEYWORDS: Tebhaga, Zamindars, Jotedars, Bargadar, Exploitations, Kisan Sabha INTRODUCTION Tebhaga Movement was an uprising against the oppressive British Raj. Tebhaga , simply put, meant that two- thirds of the crops tilled by the bargadars and adhiars would have to go to them. -

Searchable PDF Format

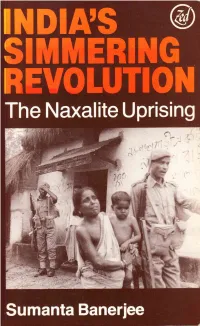

lndia's Simmering Revolution Sumanta Banerjee lndia's Simmeri ng Revolution The Naxalite Uprising Sumanta Banerjee Contents India's Simmering Revolution was first published in India under the title In the llake of Naxalbari: A History of the Naxalite Movement lVlirps in India by Subarnarekha, 73 Mahatma Gandhi Road, Calcutta 700 1 009 in 1980; republished in a revised and updated edition by Zed lrr lr<lduction Books Ltd., 57 Caledonian Road, London Nl 9BU in 1984. I l'lrc Rural Scene I Copyright @ Sumanta Banerjee, 1980, 1984 I lrc Agrarian Situationt 1966-67 I 6 Typesetting by Folio Photosetting ( l'l(M-L) View of Indian Rural Society 7 Cover photo courtesy of Bejoy Sen Gupta I lrc Government's Measures Cover design by Jacque Solomons l lrc Rural Tradition: Myth or Reality? t2 Printed by The Pitman Press, Bath l't'lrstnt Revolts t4 All rights reserved llre Telengana Liberation Struggle 19 ( l'l(M-L) Programme for the Countryside 26 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Banerjee, Sumanta ' I'hc Urban Scene 3l India's simmering revolution. I lrc Few at the ToP JJ l. Naxalite Movement 34 I. Title I lro [ndustrial Recession: 1966-67 JIa- 322.4'z',0954 D5480.84 I lre Foreign Grip on the Indian Economy 42 rsBN 0-86232-038-0 Pb ( l'l(M-L) Views on the Indian Bourgeoisie ISBN 0-86232-037-2 Hb I lrc Petty Bourgeoisie 48 I lro Students 50 US Distributor 53 Biblio Distribution Center, 81 Adams Drive, Totowa, New Jersey l lrc Lumpenproletariat 0'1512 t lhe Communist Party 58 I lrc Communist Party of India: Before 1947 58 I lrc CPI: After 1947 6l I lre Inner-Party Struggle Over Telengana 64 I he CPI(M) 72 ( 'lraru Mazumdar's Theories 74 .l Nlxalbari 82 l'lre West Bengal United Front Government 82 Itcginnings at Naxalbari 84 Assessments Iconoclasm 178 The Consequences Attacks on the Police 182 Dissensions in the CPI(M) Building up the Arsenal 185 The Co-ordination Committee The Counter-Offensive 186 Jail Breaks 189 5. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Ihi •• ",,,,I. ""!'!!". \ "I. I. '\ ... Thllr"I"~. (klohn ZI. 1'/'1') ..\"illa 2'1, 1'/21 (S;,";!) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) First Session (Thirteenth Lok Sabha) ri-.i~ , .. " ., ~.-......../j . " \ ... 30 .s;, ~ I ........ - .-.- .-" . , -_. -. - (1'01. I cOllta;n,~ Nos. I (0 8) LOK SABIIA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI !'YlfI' II" 511 ()(I EDITORIAL BOARD G.C. Malhotra Secretary-General Lok Sabtla Dr. A.K. Pandey Additional Secretary Harnam Singh Joint Secretary P.C. Bhatt ChIEl' Editor A.P. Chakravarti Senior Editor J.C. Sharma Editor (Original English Proceedings included in English Version and Original Hindi Procoedings included in Hindi Version w~1 be treated as Authoritative and not the translation thereof. CONTENTS [Thirteenth Series. Vol. I. First Session. 199911921 (Saka)] No.2, Thursday, October 21, 19991Alvlna 29, 1921 (Saka) SUBJECT Ca.UWoIS MEMBERS SWORN 1·4 LOK SABHA DEBATES LOK SABHA Shri Sohan Potai (Kanker) Shri Baliram Kashyap (Baatar) Thursday, October 21, 19991Asvlns 29, 1921 (Sau) Shri Prahladslngll Patel (Balaghat) Shri Kamal Nath (Chhlndwara) The Lok Sabha met at Eleven of the Clock Shri Vljay Kumar I<handelwal (Betul) [MR. SPEAKER PRO TEM (SHRt INORAJIT GUPTA) In the Chait) Shri Shlvraj Singh (VIdIaha) MEMBERS SWORN Shri Tarachand Patel (Khargone) {English] Shri Ramsheth Thakur (Kolaba) MR. SPEAKER: The Secretary-General may please call out the names of those Members who have not yet Shri Mohan Vishnu Rawale (Mumbal South Central) taken the oath or made the affirmation. Shri Vilas Muttemwar (Nagpur) Kumari Uma Bharati (Bhopal) Shri Diwathe Namdeo Harbaji (Chlmur) Shri V. Sreenivasaprasad (Chamarajanagar) Shri Nareshkumar Chunnalal Puglia (Chandrapur) Shri 1.0.