The Interviews: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Bengal's Rise and Fall

kheya bag RED BENGAL’S RISE AND FALL he ouster of West Bengal’s Communist government after 34 years in power is no less of a watershed for having been widely predicted. For more than a generation the Party had shaped the culture, economy and society of one of the most Tpopulous provinces in India—91 million strong—and won massive majorities in the state assembly in seven consecutive elections. West Bengal had also provided the bulk of the Communist Party of India– Marxist (cpm) deputies to India’s parliament, the Lok Sabha; in the mid-90s its Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, had been spoken of as the pos- sible Prime Minister of a centre-left coalition. The cpm’s fall from power also therefore suggests a change in the equation of Indian politics at the national level. But this cannot simply be read as a shift to the right. West Bengal has seen a high degree of popular mobilization against the cpm’s Beijing-style land grabs over the past decade. Though her origins lie in the state’s deeply conservative Congress Party, the challenger Mamata Banerjee based her campaign on an appeal to those dispossessed and alienated by the cpm’s breakneck capitalist-development policies, not least the party’s notoriously brutal treatment of poor peasants at Singur and Nandigram, and was herself accused by the Communists of being soft on the Maoists. The changing of the guard at Writers’ Building, the seat of the state gov- ernment in Calcutta, therefore raises a series of questions. First, why West Bengal? That is, how is it that the cpm succeeded in establishing -

Model Poly Biomedical and Other Diploma Courses Prospectus 2017

INSTITUTE OF HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT (Established by Government of Kerala) ONLINE ADMISSION TO ENGINEERING DIPLOMA COURSES Website: www.ihrdmptc.org PROSPECTUS 2017–18 (Prospectus issued for previous years are not valid for 2017-18) 1 INSTITUTE OF HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT (Established by the Government of Kerala) Admission to Engineering Diploma Courses 2017 – 2018 P R O S P E C T U S (Prospectus issued for previous years are not valid for 2017-18) 1. INSTITUTIONS AND COURSES OF STUDY 1.1 Three year courses, consisting of six semesters, leading to the award of Diploma in Engineering / Technology in various branches of study are offered in the following Model Polytechnic Colleges (MPTCs) managed by the Institute of Human Resources Development, Thiruvananthapuram. Applications for admission to these Polytechnic Colleges, for the academic year 2017 – 2018, are invited through online. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Name of Institution Branch of Study Annual Intake ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (1) Model Polytechnic College 1. Electronics Engineering 60 Nut Street, Vadakara 2. Bio Medical Engineering 60 Kozhikode - 673 104 3. Computer Hardware Engineering 60 (2) K Karunakaran Memmorial 1. Electronics Engineering 60 Model Polytechnic College 2. Computer Hardware Engineering 60 Mala, Kallettumkara (PO), 3. Computer Engineering 60 Thrissur - 680 683 4. Bio Medical Engineering 60 (3) Model Polytechnic College 1. Electronics Engineering 60 Mattakkara 2. Computer Hardware Engineering 60 Kottayam - 686 564 3. Electronics&Communication Engineering 50 (4) E K Nayanar Memorial 1. Computer Hardware Engineering 60 Model Polytechnic College 2. Bio Medical Engineering 60 Kalliassery, 3. Electronics&Communication Engineering 60 Kannur - 670 562 (5) Model Polytechnic College 1. Bio Medical Engineering 60 Painavu 2. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

Self Respect Movement Under Periyar

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 SELF RESPECT MOVEMENT UNDER PERIYAR M. Nala Assistant Professor of History Sri Sarada College for Women (Autonomous), Salem- 16 Self Respect Movement represented the Dravidian reaction against the Aryan domination in the Southern Society. It also armed at liberating the society from the evils of religious, customs and caste system. They tried to give equal status to the downtrodden and give the social dignity, Self Respect Movement was directed by the Dravidian communities against the Brahmanas. The movement wanted a new cultural society more based on reason rather than tradition. It aimed at giving respect to the instead of to a Brahmin. By the 19th Century Tamil renaissance gained strength because of the new interest in the study of the classical culture. The European scholars like Caldwell Beschi and Pope took a leading part in promoting this trend. C.V. Meenakshi Sundaram and Swaminatha Iyer through their wirtings and discourse contributed to the ancient glory of the Tamil. The resourceful poem of Bharathidasan, a disciple of Subramania Bharati noted for their style, beauty and force. C.N. Annadurai popularized a prose style noted for its symphony. These scholars did much revolutionise the thinking of the people and liberate Tamil language from brahminical influence. Thus they tried resist alien influence especially Aryan Sanskrit and to create a new order. The chief grievance of the Dravidian communities was their failure to obtain a fair share in the administration. Among then only the caste Hindus received education in the schools and colleges, founded by the British and the Christian missionaries many became servants of the Government, of these many were Brahmins. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

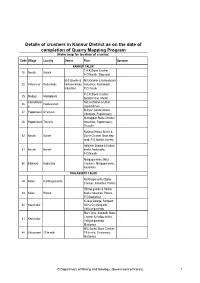

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O. -

District Survey Report of Minor Minerals (Except River Sand)

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF MINOR MINERALS (EXCEPT RIVER SAND) Prepared as per Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 issued under Environment (Protection) Act 1986 by DEPARTMENT OF MINING AND GEOLOGY www.dmg.kerala.gov.in November, 2016 Thiruvananthapuram Table of Contents Page no. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Administration ........................................................................................................................... 3 3 Drainage and Irrigation .............................................................................................................. 3 4 Rainfall and climate.................................................................................................................... 4 5 Other meteorological parameters ............................................................................................. 6 5.1 Temperature .......................................................................................................................... 6 5.2 Relative Humidity ................................................................................................................... 6 5.3 Evaporation ............................................................................................................................ 6 5.4 Sunshine Hours ..................................................................................................................... -

Kannur School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 13001 Govt H S Pulingome G 13002 St. Marys H S Cherupuzha a 13003 St

Kannur School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 13001 Govt H S Pulingome G 13002 St. Marys H S Cherupuzha A 13003 St. Josephs English High School P 13004 Govt V H S S for Girls Kannur G 13005 Govt V H S S Kannur G 13006 ST TERESAS AIHSS KANNUR A 13007 ST MICHAELS AIHSS KANNUR A 13008 TOWN GHSS KANNUR G 13009 Govt. City High School, Kannur G 13010 DIS GIRLS HSS KANNUR CITY A 13011 Deenul Islam Sabha E M H S P 13012 GHSS PALLIKUNNU G 13013 CHOVVA HSS, CHOVVA A 13014 CHM HSS ELAYAVOOR A 13015 Govt. H S S Muzhappilangad G 13016 GHSS THOTTADA G 13017 Azhikode High School, Azhikode A 13018 Govt. High School Azhikode G 13019 Govt. Regional Fisheries Technical H S G 13020 CHMS GOVT. H S S VALAPATTANAM G 13021 Rajas High School Chirakkal A 13022 Govt. High School Puzhathi G 13023 Seethi Sahib H S S Taliparamba A 13024 Moothedath H S Taliparamba A 13025 Tagore Vidyanikethan Govt. H S S G 13026 GHSS KOYYAM G 13027 GHSS CHUZHALI G 13028 Govt. Boys H S Cherukunnu G 13029 Govt. Girls V H S S Cherukunnu G 13030 C H M K S G H S S Mattool G 13032 Najath Girls H S Mattool North P.O P 13033 Govt. Boys High School Madayi G 13034 Govt. H S S Kottila G 13035 Govt. Higher Secondary School Cheruthazham G 13036 Govt. Girls High School Madayi G 13037 Jama-Ath H S Puthiyangadi A 13038 Cresent E M H S Mattambram P 13039 Govt. -

Preliminary Pages.Qxd

State Formation and Radical Democracy in India State Formation and Radical Democracy in India analyses one of the most important cases of developmental change in the twentieth century, namely, Kerala in southern India, and asks whether insurgency among the marginalized poor can use formal representative democracy to create better life chances. Going back to pre-independence, colonial India, Manali Desai takes a long historical view of Kerala and compares it with the state of West Bengal, which like Kerala has been ruled by leftists but has not experienced the same degree of success in raising equal access to welfare, literacy and basic subsistence. This comparison brings historical state legacies, as well as the role of left party formation and its mode of insertion in civil society to the fore, raising the question of what kinds of parties can effect the most substantive anti-poverty reforms within a vibrant democracy. This book offers a new, historically based explanation for Kerala’s post- independence political and economic direction, drawing on several comparative cases to formulate a substantive theory as to why Kerala has succeeded in spite of the widespread assumption that the Indian state has largely failed. Drawing conclusions that offer a divergence from the prevalent wisdoms in the field, this book will appeal to a wide audience of historians and political scientists, as well as non-governmental activists, policy-makers, and those interested in Asian politics and history. Manali Desai is Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Kent, UK. Asia’s Transformations Edited by Mark Selden Binghamton and Cornell Universities, USA The books in this series explore the political, social, economic and cultural consequences of Asia’s transformations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. -

Left Front Government in West Bengal (1971-1982) (PP93)

People, Politics and Protests VIII LEFT FRONT GOVERNMENT IN WEST BENGAL (1971-1982) Considerations on “Passive Revolution” & the Question of Caste in Bengal Politics Atig Ghosh 2017 LEFT FRONT GOVERNMENT IN WEST BENGAL (1971-1982) Considerations on “Passive Revolution” & the Question of Caste in Bengal Politics ∗ Atig Ghosh The Left Front was set up as the repressive climate of the Emergency was relaxed in January 1977. The six founding parties of the Left Front, i.e. the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or the CPI(M), the All India Forward Bloc (AIFB), the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP), the Marxist Forward Bloc (MFB), the Revolutionary Communist Party of India (RCPI) and the Biplabi Bangla Congress (BBC), articulated a common programme. This Left Front contested the Lok Sabha election in an electoral understanding together with the Janata Party and won most of the seats it contested. Ahead of the subsequent June 1977 West Bengal Legislative Assembly elections, seat- sharing talks between the Left Front and the Janata Party broke down. The Left Front had offered the Janata Party 56 per cent of the seats and the post as Chief Minister to JP leader Prafulla Chandra Sen, but JP insisted on 70 per cent of the seats. The Left Front thus opted to contest the elections on its own. The seat-sharing within the Left Front was based on the “Promode Formula”, named after the CPI(M) State Committee Secretary Promode Das Gupta. Under the Promode Formula the party with the highest share of votes in a constituency would continue to field candidates there, under its own election symbol and manifesto. -

Infographic Viceroys of India (1931-1948) 4 Octo 2018.Cdr

LORD WILLINGDON (1931-1936) Administraon Government of India Act of 1935 proposed All India federaon, bicameral legislature at centre, provincial autonomy, three lists for legislaon etc Naonal Movement Second Round Table Conference (1931) Gandhi ji aended as a Congress' Representave. Britain at that me was dominated by the Conservaves; Gandhi ji pleased for Self Rule in India but could not be successful to convince Brish Government. It proved fruitless. Demands for Separate Electorate also disrupted the discussion. Gandhi ji returned empty handed and revived the Civil Disobedience Movement. Brish Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald introduced Communal Award 1932 providing separate communal electorates in India for Muslims, Depressed, Sikhs, Indian Chrisans, Anglo-Indians etc to divide Indians and to weaken the naonal movement in India. Gandhi ji opposed it with “Fast unto Death” that led to Poona Pact 1932 between Gandhi ji and Ambedker. The Pact deals with the provisions regarding fair representaon of backward classes. Third Round Table Conference (1932) too was failed. Neither Gandhi ji, nor Congress aended it. Establishment of All India Kisan Sabha (1936) & Congress Socialist Party by Acharya Narendra Dev and Jayprakash Narayan (1934). Launch of Individual Civil Disobedience Movements (1933) by supporters of Gandhi ji aer his arrest. Judiciary GOI Act 1935 provided for the establishment of the Federal Court of India that funconed unll Supreme Court of India came into existence. LORD LINLITHGOW (1936-1944) Longest reign as Viceroy of India Administraon Government of India Act 1935 enforced in Provinces going to elecons. Naonal Movement General Elecons (1936-37) Congress formed government. Formaon of the Forward Bloc (1939) by Subhas Chandra Bose, aer he resigned from Congress, to carry on an-imperialist struggle. -

Inspiring Songs on Women Empowerment by Mahakavi Subramania Bharati

IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 10, Ver. 11 (October.2016) PP 24-28 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Inspiring Songs on Women Empowerment by Mahakavi Subramania Bharati Shobha Ramesh Carnatic Classical Musician, All India Radio Artist and Performer,B.Ed,M.Phil,Cultural Studies and Music,Jain University,Bangalore,India Abstract:-In early India, in the name of tradition, men had for long suppressed women and had deprived them of their rightful place in society. Even in the mid-nineteenth century, women had absolutely negligible rights in Indian society and had to be subjugated to their husbands and others in society.Literacy among women was not given any importance in Indian society as a woman’s role as a male caretaker, wife or mother only took precedence. Even today, in many remote villages and very conservative households, women are supposed to cover their heads with the ‘pallu’(one portion) of their saris (the traditional attire of women in India)in the presence of elders and are not allowed to voice their opinions freely or even express their desires freely in their household. This great Indian freedom fighter and poet Mahakavi Subramania Bharati brought to light the oppression against women in the male-dominated Indian society through his awe-inspiring songs on women empowerment wherein he envisaged a new strong woman of the future, who he termed as a ‘new-age woman’. He envisaged the new-age woman as one who brakes free from all the chains that bind her to customs,traditions and age-old beliefs, as one who marches ahead confidently to find an identity of her own, one who walks hand in hand with her male counterpart, equal to him in all walks of life Keywords: Women, male-domination, Mahakavi Subramania Bharati, new-age woman, empowerment I.