Más Allá Del Fin Nº 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Máriom A. Carvajal1 & Eduardo I. Faúndez1, 2 Notas Acerca De La

Boletín de Biodiversidad de Chile 6: 30–32 (2011) http://www.bbchile.com/ ______________________________________________________________________________________________ NOTES ON THE DISTRIBUTION OF IDIOSTOLUS INSULARIS BERG, 1883 HEMIPTERA: HETEROPTERA: IDIOSTOLIDAE) Máriom A. Carvajal1 & Eduardo I. Faúndez1, 2 1 Centro de Estudios en Biodiversidad (CEBCh), Magallanes, 1979, Osorno, Chile, [email protected]. 2 Grupo Entomon, Laboratorio de Entomología, Instituto de la Patagonia, Universidad de Magallanes, Avenida Bulnes 01855, Casilla 113-D, Punta Arenas, Chile, [email protected]. Abstract Mistakes about the limits in the distribution of Idiostolus insularis Berg, 1883 are discussed and corrected. The northern limit for I. insularis is established in Río Blanco, Curacautín, Araucanía Region, Chile *38°26’S-71°53’W+. New records for I. insularis are provided which present new information on the biology and distribution of this species. Key words: Idiostolidae, Idiostolus insularis, distribution, Chile, New record. Notas Acerca de la distribución de Idiostolus insularis Berg, 1883 Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Idiostolidae) Resumen Se discuten y corrigen errores existentes acerca de los límites de la distribución de Idiostolus insularis Berg, 1883, estableciéndose Río Blanco, Curacautín, Región de la Araucanía *38°26’S-71°53’W+, como límite norte para esta especie. Se entregan nuevos registros que aportan nueva información acerca de la biología y distribución de esta especie. Palabras clave: Idiostolidae, Idiostolus insularis, distribución, Nuevo registro. Idiostolidae is a family of Heteroptera which shows a classic Gondwanaland distribution (Schaefer & Wilcox, 1969). There are few data about the biology of this family. It is only known that idiostolids are phytophagous insects and are associated with Nothofagus (Nothofagaceae) forests (Scudder, 1962; Schaefer & Wilcox, 1969). -

Impact of Extreme Weather Events on Aboveground Net Primary Productivity and Sheep Production in the Magellan Region, Southernmost Chilean Patagonia

geosciences Article Impact of Extreme Weather Events on Aboveground Net Primary Productivity and Sheep Production in the Magellan Region, Southernmost Chilean Patagonia Pamela Soto-Rogel 1,* , Juan-Carlos Aravena 2, Wolfgang Jens-Henrik Meier 1, Pamela Gross 3, Claudio Pérez 4, Álvaro González-Reyes 5 and Jussi Griessinger 1 1 Institute of Geography, Friedrich–Alexander-University of Erlangen–Nürnberg, 91054 Erlangen, Germany; [email protected] (W.J.-H.M.); [email protected] (J.G.) 2 Centro de Investigación Gaia Antártica, Universidad de Magallanes, Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 3 Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG), Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 4 Private Consultant, Punta Arenas 6200000, Chile; [email protected] 5 Hémera Centro de Observación de la Tierra, Escuela de Ingeniería Forestal, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Mayor, Camino La Pirámide 5750, Huechuraba, Santiago 8580745, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 June 2020; Accepted: 13 August 2020; Published: 16 August 2020 Abstract: Spatio-temporal patterns of climatic variability have effects on the environmental conditions of a given land territory and consequently determine the evolution of its productive activities. One of the most direct ways to evaluate this relationship is to measure the condition of the vegetation cover and land-use information. In southernmost South America there is a limited number of long-term studies on these matters, an incomplete network of weather stations and almost no database on ecosystems productivity. In the present work, we characterized the climate variability of the Magellan Region, southernmost Chilean Patagonia, for the last 34 years, studying key variables associated with one of its main economic sectors, sheep production, and evaluating the effect of extreme weather events on ecosystem productivity and sheep production. -

Torres Del Paine National Park, Patagonia – Chile 2012: Work Experience in Extreme Behavior Conditions 1 in the Context of Global Warming

Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Fire Economics, Planning, and Policy: Climate Change and Wildfires Mega Wildfire in the World Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO), Torres del Paine National Park, Patagonia – Chile 2012: Work Experience In Extreme Behavior Conditions 1 in the Context of Global Warming René Cifuentes Medina2 Abstract Mega wildfires are critical, high-impact events that cause severe environmental, economic and social damage, resulting, in turn, in high-cost suppression operations and the need for mutual support, phased use of resources and the coordinated efforts of civilian government agencies, the armed forces, private companies and the international community. The mega forest fire that struck the Torres del Paine National Park and World Biosphere Reserve in the southern Magallanes region of Chile, in the period from December 2011 to February 2012, was caused by the negligent act of a tourist, in an area of difficult access by land and under extreme behavior conditions that made rapid access of ground attack resources even more difficult and made air attack impossible. Factors that influenced the event from the beginning were rapid rate of spread, high caloric intensity, resistance to control and long- distance emission of firebrands. On the other hand, the effects of climate change and global warming are being felt and viewed worldwide as a real threat, generating perfect scenarios for the occurrence of fires of this kind. Thus, this fire serves as a concrete example worthy of analysis for its magnitude, the considerable resources and means used, the level of complexity in attack operations, the great logistical deployments that had to be implemented due to the remoteness and inaccessibility of the site, the complications that had to be overcome, its impact on tourism and the local economy, the extensive media coverage it received, and its considerable political impact. -

First Meeting “Cystic Echinococcosis in Chile, Update in Alternatives for Control and Diagnostics in Animals and Humans” Cristian A

Alvarez Rojas et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:502 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1792-y MEETINGREPORT Open Access First meeting “Cystic echinococcosis in Chile, update in alternatives for control and diagnostics in animals and humans” Cristian A. Alvarez Rojas1*, Fernando Fredes2, Marisa Torres3, Gerardo Acosta-Jamett4, Juan Francisco Alvarez5, Carlos Pavletic6, Rodolfo Paredes7* and Sandra Cortés3,8 Abstract This report summarizes the outcomes of a meeting on cystic echinococcosis (CE) in animals and humans in Chile held in Santiago, Chile, between the 21st and 22nd of January 2016. The meeting participants included representatives of the Departamento de Zoonosis, Ministerio de Salud (Zoonotic Diseases Department, Ministry of Health), representatives of the Secretarias Regionales del Ministerio de Salud (Regional Department of Health, Ministry of Health), Instituto Nacional de Desarrollo Agropecuario (National Institute for the Development of Agriculture and Livestock, INDAP), Instituto de Salud Pública (National Institute for Public Health, ISP) and the Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (Animal Health Department, SAG), academics from various universities, veterinarians and physicians. Current and future CE control activities were discussed. It was noted that the EG95 vaccine was being implemented for the first time in pilot control programmes, with the vaccine scheduled during 2016 in two different regions in the South of Chile. In relation to use of the vaccine, the need was highlighted for acquiring good quality data, based on CE findings at slaughterhouse, previous to initiation of vaccination so as to enable correct assessment of the efficacy of the vaccine in the following years. The current world’s-best-practice concerning the use of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool for the screening population in highly endemic remote and poor areas was also discussed. -

Slime Moulds

Queen’s University Biological Station Species List: Slime Molds The current list has been compiled by Richard Aaron, a naturalist and educator from Toronto, who has been running the Fabulous Fall Fungi workshop at QUBS between 2009 and 2019. Dr. Ivy Schoepf, QUBS Research Coordinator, edited the list in 2020 to include full taxonomy and information regarding species’ status using resources from The Natural Heritage Information Centre (April 2018) and The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (February 2018); iNaturalist and GBIF. Contact Ivy to report any errors, omissions and/or new sightings. Based on the aforementioned criteria we can expect to find a total of 33 species of slime molds (kingdom: Protozoa, phylum: Mycetozoa) present at QUBS. Species are Figure 1. One of the most commonly encountered reported using their full taxonomy; common slime mold at QUBS is the Dog Vomit Slime Mold (Fuligo septica). Slime molds are unique in the way name and status, based on whether the species is that they do not have cell walls. Unlike fungi, they of global or provincial concern (see Table 1 for also phagocytose their food before they digest it. details). All species are considered QUBS Photo courtesy of Mark Conboy. residents unless otherwise stated. Table 1. Status classification reported for the amphibians of QUBS. Global status based on IUCN Red List of Threatened Species rankings. Provincial status based on Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre SRank. Global Status Provincial Status Extinct (EX) Presumed Extirpated (SX) Extinct in the -

Biodiversity of Plasmodial Slime Moulds (Myxogastria): Measurement and Interpretation

Protistology 1 (4), 161–178 (2000) Protistology August, 2000 Biodiversity of plasmodial slime moulds (Myxogastria): measurement and interpretation Yuri K. Novozhilova, Martin Schnittlerb, InnaV. Zemlianskaiac and Konstantin A. Fefelovd a V.L.Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia, b Fairmont State College, Fairmont, West Virginia, U.S.A., c Volgograd Medical Academy, Department of Pharmacology and Botany, Volgograd, Russia, d Ural State University, Department of Botany, Yekaterinburg, Russia Summary For myxomycetes the understanding of their diversity and of their ecological function remains underdeveloped. Various problems in recording myxomycetes and analysis of their diversity are discussed by the examples taken from tundra, boreal, and arid areas of Russia and Kazakhstan. Recent advances in inventory of some regions of these areas are summarised. A rapid technique of moist chamber cultures can be used to obtain quantitative estimates of myxomycete species diversity and species abundance. Substrate sampling and species isolation by the moist chamber technique are indispensable for myxomycete inventory, measurement of species richness, and species abundance. General principles for the analysis of myxomycete diversity are discussed. Key words: slime moulds, Mycetozoa, Myxomycetes, biodiversity, ecology, distribu- tion, habitats Introduction decay (Madelin, 1984). The life cycle of myxomycetes includes two trophic stages: uninucleate myxoflagellates General patterns of community structure of terrestrial or amoebae, and a multi-nucleate plasmodium (Fig. 1). macro-organisms (plants, animals, and macrofungi) are The entire plasmodium turns almost all into fruit bodies, well known. Some mathematics methods are used for their called sporocarps (sporangia, aethalia, pseudoaethalia, or studying, from which the most popular are the quantita- plasmodiocarps). -

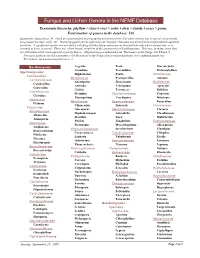

9B Taxonomy to Genus

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella -

Slime Molds: Biology and Diversity

Glime, J. M. 2019. Slime Molds: Biology and Diversity. Chapt. 3-1. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 2. Bryological 3-1-1 Interaction. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 18 July 2020 and available at <https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 3-1 SLIME MOLDS: BIOLOGY AND DIVERSITY TABLE OF CONTENTS What are Slime Molds? ....................................................................................................................................... 3-1-2 Identification Difficulties ...................................................................................................................................... 3-1- Reproduction and Colonization ........................................................................................................................... 3-1-5 General Life Cycle ....................................................................................................................................... 3-1-6 Seasonal Changes ......................................................................................................................................... 3-1-7 Environmental Stimuli ............................................................................................................................... 3-1-13 Light .................................................................................................................................................... 3-1-13 pH and Volatile Substances -

Application of Technologies to Improve Nothofagus Pumilio Restoration in Chilean Patagonia

Application of technologies to improve Nothofagus pumilio restoration in Chilean Patagonia. Eduardo Arellano, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile. Additional Authors: Patricio Valenzuela, Pablo Becerra Throughout history Patagonian forests have been converted to other land uses such as grazing and mining. Surface coal mining in Chilean Patagonian region results in forest and grassland disturbance, altering the landscape and affecting sensitive vegetation naturally adapted to grow in extreme site conditions. Previous reclamation experiences have been focuses on restoring grassland using exotic herbaceous species. There are no local experiences on restoring native Nothofagus forest due to poor reforestation practices that not consider seedling sensibility to soil moisture stress and windy conditions that normally end in high seedling mortality. Using the forest reclamation approach model, we previously identified microsite conditions that promote natural regeneration. Despite the high landscape variability, natural forest regeneration occurs on microsite condition where shrubs and native grasses protect the seedling. Our objective was to explore which biotic and abiotic factors favor Nothofagus pumilio reforestation following anthropic disturbance. The study have been conducted in Magallanes Region in Chilean Patagonia, 130 Km north from Punta Arenas, in the Riesco Island. The climate is an oceanic climate bordering on a tundra climate. The seasonal temperature is greatly moderated by its proximity to the ocean, with average lows in July near −1 °C and highs in January of 14 °C, the average precipitation is 450 mm. We conducted a randomized split plot experiment to examine the effects of woody debris, shrubs, and shelters on seedlings growth, and survival during first year following planting in a mined site where top soil was replace and in grassland. -

Glacier Fluctuations During the Past 2000 Years

Quaternary Science Reviews 149 (2016) 61e90 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Invited review Glacier fluctuations during the past 2000 years * Olga N. Solomina a, , Raymond S. Bradley b, Vincent Jomelli c, Aslaug Geirsdottir d, Darrell S. Kaufman e, Johannes Koch f, Nicholas P. McKay e, Mariano Masiokas g, Gifford Miller h, Atle Nesje i, j, Kurt Nicolussi k, Lewis A. Owen l, Aaron E. Putnam m, n, Heinz Wanner o, Gregory Wiles p, Bao Yang q a Institute of Geography RAS, Staromonetny-29, 119017 Staromonetny, Moscow, Russia b Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA c Universite Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne, CNRS Laboratoire de Geographie Physique, 92195 Meudon, France d Department of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland, Askja, Sturlugata 7, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland e School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, USA f Department of Geography, Brandon University, Brandon, MB R7A 6A9, Canada g Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales (IANIGLA), CCT CONICET Mendoza, CC 330 Mendoza, Argentina h INSTAAR and Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, USA i Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen, Allegaten 41, N-5007 Bergen, Norway j Uni Research Climate AS at Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway k Institute of Geography, University of Innsbruck, Innrain 52, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria l Department of Geology, -

The Mycetozoa of North America, Based Upon the Specimens in The

THE MYCETOZOA OF NORTH AMERICA HAGELSTEIN, MYCETOZOA PLATE 1 WOODLAND SCENES IZ THE MYCETOZOA OF NORTH AMERICA BASED UPON THE SPECIMENS IN THE HERBARIUM OF THE NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN BY ROBERT HAGELSTEIN HONORARY CURATOR OF MYXOMYCETES ILLUSTRATED MINEOLA, NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR 1944 COPYRIGHT, 1944, BY ROBERT HAGELSTEIN LANCASTER PRESS, INC., LANCASTER, PA. PRINTED IN U. S. A. To (^My CJriend JOSEPH HENRI RISPAUD CONTENTS PAGES Preface 1-2 The Mycetozoa (introduction to life history) .... 3-6 Glossary 7-8 Classification with families and genera 9-12 Descriptions of genera and species 13-271 Conclusion 273-274 Literature cited or consulted 275-289 Index to genera and species 291-299 Explanation of plates 301-306 PLATES Plate 1 (frontispiece) facing title page 2 (colored) facing page 62 3 (colored) facing page 160 4 (colored) facing page 172 5 (colored) facing page 218 Plates 6-16 (half-tone) at end ^^^56^^^ f^^ PREFACE In the Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden are the large private collections of Mycetozoa made by the late J. B. Ellis, and the late Dr. W. C. Sturgis. These include many speci- mens collected by the earlier American students, Bilgram, Farlow, Fullmer, Harkness, Harvey, Langlois, Macbride, Morgan, Peck, Ravenel, Rex, Thaxter, Wingate, and others. There is much type and authentic material. There are also several thousand specimens received from later collectors, and found in many parts of the world. During the past twenty years my associates and I have collected and studied in the field more than ten thousand developments in eastern North America. -

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow At

on fellow ous L g ulletinH e Volume No. A Newsletter of the Friends of the Longfellow House and the National Park Service December pecial nniversary ssue House SelectedB As Part of Underground Railroad Network to Freedom S Henry WadsworthA LongfellowI he Longfellow National Historic Site apply for grants dedicated to Underground Turns 200 Thas been awarded status as a research Railroad preservation and research. ebruary , , marks the th facility with the Na- This new national Fanniversary of the birth of America’s tional Park Service’s Network also seeks first renowned poet, Henry Wadsworth Underground Railroad to foster communi- Longfellow. Throughout the coming year, Network to Freedom cation between re- Longfellow NHS, Harvard University, (NTF) program. This searchers and inter- Mount Auburn Cemetery, and the Maine program serves to coor- ested parties, and to Historical Society will collaborate on dinate preservation and help develop state- exhibits and events to observe the occa- education efforts na- wide organizations sion. (See related articles on page .) tionwide and link a for preserving and On February the Longfellow House multitude of historic sites, museums, and researching Underground Railroad sites. and Mount Auburn Cemetery will hold interpretive programs connected to various Robert Fudge, the Chief of Interpreta- their annual birthday celebration, for the facets of the Underground Railroad. tion and Education for the Northeast first time with the theme of Henry Long- This honor will allow the LNHS to dis- Region of the NPS, announced the selec- fellow’s connections to abolitionism. Both play the Network sign with its logo, receive tion of the Longfellow NHS for the Un- historic places will announce their new technical assistance, and participate in pro- derground Railroad Network to Freedom status as part of the NTF.