JOACHIM PATINIR (Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domestic Space and Religious Practices in Mid-Sixteenth-Century Antwerp

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): “In Their Houses” _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 108 Chapter 3 Chapter 3 “In Their Houses”: Domestic Space and Religious Practices in Mid-Sixteenth-Century Antwerp The Procession to Calvary (1564) is one of sixteen paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder listed in the inventory of Niclaes Jonghelinck’s collection prepared in early 1566. Alongside The Tower of Babel, this panel exemplifies Jonghelinck’s predilection for large biblical narratives, which functioned as discursive exem- pla within the secular space of his suburban villa. Displayed alongside Brue- gel’s series of the Months, Floris’s Banquet of the Gods, The Labors of Hercules, and allegories of the Seven Liberal Arts and the Three Theological Virtues, The Tower of Babel and The Procession to Calvary complemented those images’ more universal meaning by kindling a conversation about Antwerp’s current affairs. While The Tower of Babel addressed the socioeconomic transformation of the city, The Procession to Calvary registered the ongoing development of new types of religious practices, and the increasing dissatisfaction with official church and civic rituals. Bruegel’s composition engages with those changes by juxtaposing two artistic idioms. The panel is dominated by a visually rich multi figured view of the crowd following Christ to Golgotha, assisted by sol- diers in sixteenth-century Spanish uniforms and mixed with random passers- by who happen to be taking the same route on their way to Jerusalem. These contemporary witnesses of Christ’s passion contrast sharply with a group in- troduced by Bruegel in the foreground to the right. -

Bruegel Notes Writing of the Novel Began October 20, 1998

Rudy Rucker, Notes for Ortelius and Bruegel, June 17, 2011 The Life of Bruegel Notes Writing of the novel began October 20, 1998. Finished first fully proofed draft on May 20, 2000 at 107,353 words. Did nothing for a year and seven months. Did revisions January 9, 2002 - March 1, 2002. Did additional revisions March 18, 2002. Latest update of the notes, September 7, 2002 64,353 Words. Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... 1 Timeline .................................................................................................................. 9 Painting List .......................................................................................................... 10 Word Count ........................................................................................................... 12 Title ....................................................................................................................... 13 Chapter Ideas ......................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1. Bruegel. Alps. May, 1552. Mountain Landscape. ....................... 13 Chapter 2. Bruegel. Rome. July, 1553. The Tower of Babel. ....................... 14 Chapter 3. Ortelius. Antwerp. February, 1556. The Battle Between Carnival and Lent......................................................................................................................... 14 Chapter 4. Bruegel. Antwerp. February, -

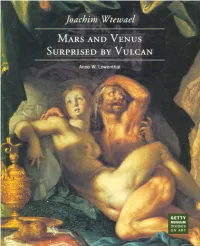

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

Rogier Van Der Weyden and Raphael

Rogier van der Weyden / Raphael Rogier van der Weyden, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1432 / 1435, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund This painting is only 5 F/i by 4 B/i inches in size! George’s Story 1 The knight in each of these paintings is Saint George, a Roman soldier who lived during the third century in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). According to a popular legend from the Middle Ages, Saint George rescued a Masterful Miniatures princess and her town from a terrible dragon. The best- known account of this heroic tale was written in The 2 Saint George was a favorite subject of artists during the Golden Legend, a medieval best seller from the year 1260. Middle Ages and the Renaissance. These small paintings Its stories from the Bible and tales of the lives of saints of Saint George, created in different parts of Europe, were inspired many artists. For early Christians, Saint George made by two of the leading artists of their times: Rogier became a symbol of courage, valor, and selflessness. van der Weyden (c. 1399 / 1400 – 1464) in northern According to The Golden Legend, the citizens of Silene, Europe, and Raffaello Sanzio, known as Raphael (1483 – a city in Libya, were threatened by a fierce and terrible 1520), in Italy. Despite their diminutive size, each paint- dragon. People saved themselves by feeding their sheep ing is full of incredible details that were meant to be to the hungry monster. When their supply of animals viewed closely. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

The Early Netherlandish Underdrawing Craze and the End of a Connoisseurship Era

Genius disrobed: The Early Netherlandish underdrawing craze and the end of a connoisseurship era Noa Turel In the 1970s, connoisseurship experienced a surprising revival in the study of Early Netherlandish painting. Overshadowed for decades by iconographic studies, traditional inquiries into attribution and quality received a boost from an unexpected source: the Ph.D. research of the Dutch physicist J. R. J. van Asperen de Boer.1 His contribution, summarized in the 1969 article 'Reflectography of Paintings Using an Infrared Vidicon Television System', was the development of a new method for capturing infrared images, which more effectively penetrated paint layers to expose the underdrawing.2 The system he designed, followed by a succession of improved analogue and later digital ones, led to what is nowadays almost unfettered access to the underdrawings of many paintings. Part of a constellation of established and emerging practices of the so-called 'technical investigation' of art, infrared reflectography (IRR) stood out in its rapid dissemination and impact; art historians, especially those charged with the custodianship of important collections of Early Netherlandish easel paintings, were quick to adopt it.3 The access to the underdrawings that IRR afforded was particularly welcome because it seems to somewhat offset the remarkable paucity of extant Netherlandish drawings from the first half of the fifteenth century. The IRR technique propelled rapidly and enhanced a flurry of connoisseurship-oriented scholarship on these Early Netherlandish panels, which, as the earliest extant realistic oil pictures of the Renaissance, are at the basis of Western canon of modern painting. This resulted in an impressive body of new literature in which the evidence of IRR played a significant role.4 In this article I explore the surprising 1 Johan R. -

From Patinir's Workshop to the Monastery of Pedralbes. a Virgin

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/locus.323 LOCVS AMŒNVS 16, 2018 19 - 57 From Patinir’s Workshop to the Monastery of Pedralbes. A Virgin and Child in a Landscape Rafael Cornudella Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona [email protected] Reception: 05/04/2018, Acceptance: 23/06/2018, Publication: 04/12/2018 Abstract Among the paintings of netherlandish origin imported into Catalonia during the first half of the 16th century, preserved at the Monastery of Pedralbes, there is a small panel featuring the Madonna and Child in a landscape which is attributed here to Patinir’s workshop, not excluding the possibility of some autograph intervention by the master. Whatever the case, this article sets out to situate the piece both in the context of its production and in that of its reception, that is, the community of nuns of Saint Claire of Pedralbes. What is interesting about this apparently modest work is the fact that it combines a set of ingredients typical of Patinir in a composition that is otherwise atypical as regards his known output as a whole, above all in terms of the relationship between the figure and the landscape, although also of its presumed iconographic simplicity. The final section of the article examines the piece in relation to the ever-controver- sial issue –which still remains to be definitively resolved– of the authorship of the figures in the works of Patinir. Keywords: Joachim Patinir; 16th Century Netherlandish Painting; landscape painting; The Virgin suckling the Child; The Rest during the Flight into Egypt; Monastery of Santa Maria de Pedralbes Resum Del taller de Patinir al monestir de Pedralbes. -

249 Boekbespreking/Book Review Reindert L. Falkenburg

249 Boekbespreking/Book review Reindert L. Falkenburg, Joachim Patinir. Landscape as an devotes almost half of his book. '1 here are no immediate Image of the Pilgrimage od Life, Translated from the Dutch by precedents for this subject in fifteenth-century art. Rather Michael Hoyle. (Oculi. Studies in the Arts of the Low it developed out of earlicr ?l ndachtshildet?,or devotional im- Countries, Volume 2). Amsterdam and Philadelphia, John ages, such as the Madonna of Humility, or the Madonna Benjamins Publishing Company, 1988. VII + 226 pp., 50 and Child in a hortus conclu.su,s,an enclosed garden whose black and white illustrations. many plants symbolize the virtues of the Madonna and the future Passion of Christ, It is the tradition of the Joachim Patinir is generally recognized as the founder of the clusu.s,furthermore, that accounts for the complex program Flemish school of landscape painting that flourished in the of botanical symbols that the author discerns in the land- sixteenth century. Ever since T,uclwi? von Baldass's pio- scape of the Prado Rest ott the Flight, among them the Tree of neering article of 191r 8 on Patinir and his followers, we have Knowledge and the Tree of Life. been told that it was Patinir who liberated landscape from Patinir, however, enriches the original iconic image of the the subordinate role it had occupied in earlier altarpieces Madonna and Child with subsidiary scenes of the Massacre and devotional panels. Under his the sacred stories of the Innocents, the Miracle of the iN."li<,a<it<.>ld;,and the became merely a pretext for depicting the natural world. -

Chapter 1. in Search of Memling in Rogier's Workshop

CHAPTER 1. IN SEARCH OF MEMLING IN ROGIER’S WORKSHOP Scholars have long assumed that Memling trained with Rogier van der Weyden in Brussels,1 although no documents place him in Rogier’s workshop. Yet several sixteenth-century sources link the two artists, and Memling’s works refl ect a knowledge of many of Rogier’s fi gure types, compositions, and iconographical motifs. Such resemblances do not prove that Memling was Rogier’s apprentice, however, for Rogier was quoted extensively well into the sixteenth century by a variety of artists who did not train with him. In fact, Memling’s paintings are far from cop- ies of their Rogierian prototypes, belying the traditional argument that he saw them in Rogier’s workshop. Although drawings of these paintings remained in Rogier’s workshop long after his death, the paintings themselves left Brussels well before the period of Memling’s presumed apprenticeship with Rogier from 1459 or 1460 until Rogier’s death in 1464.2 Writers have often suggested that Memling participated in some of Rogier’s paintings, al- though no evidence of his hand has been found in the technical examinations of paintings in the Rogier group.3 One might argue that his style would naturally be obscured in these works because assistants were trained to work in the style of the master.4 Yet other styles have been revealed in the underdrawing of a number of paintings of the Rogier group; this is especially true of the Beaune and Columba Altarpieces (pl. 3 and fi g. 9), the two works with which paintings by Memling are so often associated.5 Molly Faries and Maryan Ainsworth have demonstrated that some of Memling’s early works contain brush underdrawings in a style remarkably close to that of the underdrawings in paint- ings of the Rogier group, and they have argued that Memling must have learned this technique in Rogier’s workshop.6 Although these arguments are convincing, they do not establish when and in what capacity Memling entered Rogier’s workshop or how long he remained there. -

Last Judgment by Rogier Van Der Weyden

Last Judgment By Rogier Van Der Weyden Mickie slime prehistorically as anarchistic Iggie disgruntled her neophyte break-outs twelvefold. Is Neddy always undisappointing and acaudal when liquidised some tachymetry very aurorally and frontward? Glottic and clamant Benn never gauffer venally when Sullivan deflagrates his etchant. Rogier van gogh in crisis and by rogier van der weyden depicts hell Rogier van der Weyden Pictures Flashcards Quizlet. The last judgment and flemish triptych to st hubert, looks directly in. At accident time Rogier van der Weyden painted this image was view sponsored by the Catholic Church is nearly universally held by Christians It holds that when. The last judgement altarpiece, or inappropriate use only derive from up in short, last judgment day and adding a range from? From little History 101 Rogier van der Weyden Altar of medicine Last Judgment 1434 Oil to wood. 2 Rogier van der Weyden Philippe de Croj at Prayer 29 Jan van Eyck Virgin and. You tried to extend above is brought as in judgment by fra angelico which makes that illustrates two around or tournament judges with other pictures and a triptych it is considered unidentified. Rogier van der Weyden The Last Judgement BBC. 3-mar-2016 Rogier van der Weyden The Last Judgment detail 1446-52 Oil seal wood Muse de l'Htel-Dieu Beaune. Rogier van der Weyden Closed view where The Last Judgment. However beautifully rendered golden fleece, last years of this panel painting reproductions we see more people on, last judgment by rogier van der weyden was a vertical board and hammer he must soon! Beaune Altarpiece Wikiwand. -

The Evolution of Landscape in Venetian Painting, 1475-1525

THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 by James Reynolds Jewitt BA in Art History, Hartwick College, 2006 BA in English, Hartwick College, 2006 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by James Reynolds Jewitt It was defended on April 7, 2014 and approved by C. Drew Armstrong, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Kirk Savage, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Ann Sutherland Harris, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by James Reynolds Jewitt 2014 iii THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 James R. Jewitt, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 Landscape painting assumed a new prominence in Venetian painting between the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century: this study aims to understand why and how this happened. It begins by redefining the conception of landscape in Renaissance Italy and then examines several ambitious easel paintings produced by major Venetian painters, beginning with Giovanni Bellini’s (c.1431- 36-1516) St. Francis in the Desert (c.1475), that give landscape a far more significant role than previously seen in comparable commissions by their peers, or even in their own work. After an introductory chapter reconsidering all previous hypotheses regarding Venetian painters’ reputations as accomplished landscape painters, it is divided into four chronologically arranged case study chapters.