'Settled Legally but Not Socially'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Factors Responsible for Adoption of Gobindabhog Rice in Some Selected Areas of Burdwan District, West Bengal, India

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2019) 8(2): 107-113 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 8 Number 02 (2019) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2019.802.013 Factors Responsible for Adoption of Gobindabhog Rice in Some Selected Areas of Burdwan District, West Bengal, India Chowdhury Nazmul Haque*, Dinesh Das Kaibartya and Arup Kumar Bandyopadhyay Department of Agricultural Extension, Bidhan Chandra KrishiViswavidyalaya, Mohanpur, Nadia, West Bengal, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Adoption is a process of making a decision about an innovation of technology option offered to anyone. Even though we have brought about green revolution and moving for second green revolution, more than 60% of technology cannot reach the domain of farmer‟s innovation decision. So the present study takes care of adoption process of „Gobindabhog‟ famous traditional aromatic rice, to explore the process and complexity of Ke yw or ds its adoption and subsequent socialization. Aromatic rice like Gobindabhog has got social, ecological and economic importance. The general objective is estimating the factors Adoption, Aromatic responsible for adoption of Gobindabhog rice and following are the specific objectives: -1. rice, Gobindabhog To find out the relationship of the selected independent variables with the adoption behaviour of the farmers engaged in „Gobindabhog‟ rice cultivation. 2. To identify the Article Info degree to which the adoption behaviour may be predicted from this characteristics. 3. To access the different problems faced by the farmers hindering the adoption process and the Accepted: measures suggested by them as remedies. -

MGNREGA): Its Impact and Women’S Participation Dr

International Journal of Research in management ISSN 2249-5908 Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ijrm/ijrm_index.htm Issue 2, Vol. 6 (November-2012) Examining India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA): Its Impact and Women’s Participation Dr. Dinesh Das Assistant Professor, Dept. of Economics, Gossaigaon College, Kokrajhar, Assam, INDIA __________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is the central government response to the constitutionally manifested right to work and means to promote livelihood security in India’s rural areas. MGNREGA is the flagship rural employment generation programme in rural areas for 100 days in a financial year. While providing employment, priority shall be given to women in such a way that at least one-third of the beneficiaries shall be women who have registered and requested for work under the scheme. Equal wages shall be paid to both men and women workers. By generating employment for women at fair wages in the village, NREGA can play a substantial role in economically empowering women and laying the basis for greater independence and self- esteem. One of the most distinguishing features of MGNREGA is its approach towards empowering citizen including women citizen to play an active role in the implementation of the scheme, through gram sabha, social audit, participatory planning and other activities. Keywords: MGNREGA, Women’s Participation, Development, NE India __________________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Gender is the inevitable push factor for growth and development of a nation like India. In India women constitute a major share of chronically poor population. They are facing vulnerabilities of life. -

EAP188: Rescuing Text: Retrieval and Documentation of Printed Books and Periodicals Published Prior to 1950 from Public Institutions in Eastern India

EAP188: Rescuing text: retrieval and documentation of printed books and periodicals published prior to 1950 from public institutions in Eastern India This project surveyed the collections of 18 libraries in the state of West Bengal and 2 libraries in the state of Assam, producing a database of 26,579 titles. Database key The titles surveyed were checked against the OCLC Worldcat and British Library Catalogue data, and this information appears in the following spreadsheet columns: A count of 0 – no match A count of 1 – match The following libraries were surveyed, and are indicated in the spreadsheet by their acronyms: Library Name of Library Initial(s) Ariadaha AL Library Assam ASS Sahitya Sabha Bankim Bhaban BBGK Gabeshana Kendra Bansberia BPL Public Library Barisha BPTL Pustakagar O Town Library Bali Sadharan BSG Granthagar Behala Town BTL Library Chetla CNL Nityananda Library Chandannagar CP Pustakagar Department of Historical and Antiquarian DHAS Studies, Guwahati, Assam Hemchandra HP Pathagar Harinavi HPG Public Library Jadunath Sarkar Centre JSCHR for Historical Research Jaynagar Uttarpara JUBL Bandhab Library Madarhat MBP Bandhab Pathagar ML Mudiali Library Mohiari Public MPL Library Rammohan RML Library Rajpur RSP Sadharan Pathagar Further Information You can contact the EAP team at [email protected] EAP188: Rescuing text: retrieval and documentation of printed books and periodicals published prior to 1950 from public institutions in Eastern India Report on Libraries surveyed: Ө Jadunath Sarkar Resource Centre for Historical Research The Jadunath Sarkar Resource Centre for Historical Research, housed at 10, Lake Terrace, Kolkata – 700 029, is known widely for its unique and unconventional resources that are not easy to be found in other conventional libraries. -

Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950S

People, Politics and Protests I Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950s – 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Anwesha Sengupta 2016 1. Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee 1 2. Tram Movement and Teachers’ Movement in Calcutta: 1953-1954 Anwesha Sengupta 25 Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s ∗ Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Introduction By now it is common knowledge how Indian independence was born out of partition that displaced 15 million people. In West Bengal alone 30 lakh refugees entered until 1960. In the 1970s the number of people entering from the east was closer to a few million. Lived experiences of partition refugees came to us in bits and pieces. In the last sixteen years however there is a burgeoning literature on the partition refugees in West Bengal. The literature on refugees followed a familiar terrain and set some patterns that might be interesting to explore. We will endeavour to explain through broad sketches how the narratives evolved. To begin with we were given the literature of victimhood in which the refugees were portrayed only as victims. It cannot be denied that in large parts these refugees were victims but by fixing their identities as victims these authors lost much of the richness of refugee experience because even as victims the refugee identity was never fixed as these refugees, even in the worst of times, constantly tried to negotiate with powers that be and strengthen their own agency. But by fixing their identities as victims and not problematising that victimhood the refugees were for a long time displaced from the centre stage of their own experiences and made “marginal” to their narratives. -

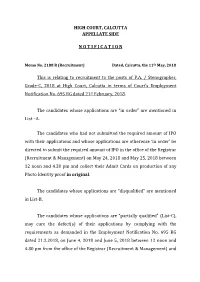

HIGH COURT, CALCUTTA APPELLATE SIDE N O T I F I C a T I O N This Is Relating to Recruitment to the Posts of P.A. / Stenographer

HIGH COURT, CALCUTTA APPELLATE SIDE N O T I F I C A T I O N Memo No. 2188 R (Recruitment) Dated, Calcutta, the 11th May, 2018 This is relating to recruitment to the posts of P.A. / Stenographer, Grade-C, 2018 at High Court, Calcutta in terms of Court’s Employment st Notification No. 695 RG dated 21 February, 2018. The candidates whose applications are “in order” are mentioned in List –A. The candidates who had not submitted the required amount of IPO with their applications and whose applications are otherwise ‘in order’ be directed to submit the required amount of IPO in the office of the Registrar (Recruitment & Management) on May 24, 2018 and May 25, 2018 between 12 noon and 4.30 pmin and original collect their Admit Cards on production of any Photo Identity proof . The candidates whose applications are “disqualified” are mentioned in List-B. The candidates whose applications are “partially qualified” (List-C), may cure the defect(s) of their applications by complying with the requirements as demanded in the Employment Notification No. 695 RG dated 21.2.2018, on June 4, 2018 and June 5, 2018 between 12 noon and 4.30 pm from the office of the Registrar (Recruitment & Management) and in collectoriginal. their Admit Cards on production of any Photo Identity proof In respect of the candidates in the group “partially qualified” (List-C), the defects are indicated in the “modalities of scrutiny” list (List-D). Sd/- Registrar (Recruitment & Management), A.S, High Court, Calcutta. LIST- A (IN ORDER) Sl. -

Unpaid Dividend- 2014-2015

Cheque No Warrant No Warrant Date Folio No Amount Beneficiary Name 13 3512 10-Sep-2015 00001207100000098876 5,000.00 VIJAYKUMAR SANGHVI 002104000072496 IDBI BANK LTD IDB 16 5250 10-Sep-2015 0000000000000G000830 100.00 GOURI GHOSH CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA SB A C NO 1601003706 22 9760 10-Sep-2015 0000000000000V000662 50.00 VIJENDER KUMAR ORIENTAL BANK OF COMMERCE SB A C NO 10482010018920 31 49 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30007910381120 100.00 DINESH ROY DEEN 063104000164023 IDBI BANK LTD 715 KATARUKA HOUSE 36 79 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30011810207110 50.00 TIRLOCHAN SINGH 7174 CANARA BANK MAIN BRANCH 41 136 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30014210112487 50.00 VIJOYA KUMARI 021 304043 006 HSBC 8 N S ROAD 42 139 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30014210150792 50.00 ANUP KUMAR PAUL 034 157750 006 HSBC P 158 46 172 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30017510080966 50.00 RAMAKRISHNAN L RMK L 3893 THE VYSYA BANK LTD SHEVAPET 50 237 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30021411751559 50.00 JAYANT SHEETALCHANDRA DUMNE 004401027729 ICICI BANK LTD GR FLOOR TAPADIA CIRCLE 51 244 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30021412530342 200.00 SHIV GOVIND RAI 20419456834 ALLAHABAD BANK G T ROAD 53 249 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30021413303973 15.00 VINAYAK MURALI 008010101332128 UTI BANK GREENLANDS BEGUMPET ROAD 60 294 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30023912932992 50.00 FARUKH MOHAMADHANIF BAGWAAN 188010100015668 AXIS BANK LTD ABANJANI 63 313 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30026310022812 650.00 JAYANTA PAUL 172901 PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK 34 C R AVENUE 64 316 10-Sep-2015 0000IN30026310063003 50.00 BHASKAR DATTA SB NM 6764 THE SANTRAGACHI CO OP BANK LTD SASTITOLA KONA ROAD BRANCH 65 317 10-Sep-2015 -

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) and Empowerment of Women from BPL Families in Rural Areas” a Case Study of District Aligarh (India)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 3, Ver. VII (Mar. 2015), PP 07-16 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org “Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) and Empowerment of Women from BPL families in rural areas” A case study of district Aligarh (India) Saleem Akhtar Farooqi1 and Dr. Imran Saleem2 1Research Scholar, Department of Commerce, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. 2Professor, Department of Commerce, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh Abstract: The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) of India is most progressive legislation enacted by parliament. This is the flagship program introduced by United Progressive Alliance Government and implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development with primary objective of providing livelihood security to rural poor of Below Poverty Line (BPL) families by providing them at least 100 days guaranteed unskilled manual work in a year. The Act has become the fact of life of rural poor and with the stipulation that 33 percent of the total work will be given to the women it provides the means to raise the socio- economic status of the rural women from BPL families. In this paper by conducting a survey of rural areas of district Aligarh (Uttar Pradesh) and by the in-depth interview of women beneficiaries it is tried to find out that up to what extent MGNREGA is helpful for women empowerment by raising their standard of living through the provision of 100 days guaranteed employment. The paper also highlights the factors influencing the participation of women in the scheme and needs for assessment of institutional and governance system related to the implementation of the scheme particularly the ways through which employment opportunities are offered to women. -

Introduction Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment

INTRODUCTION MAHATMA GANDHI NATIONAL RURAL EMPLOYMENT GUARANTEE SCHEME Today, the MGNREGA has provided an employment to millions of workers not only the employment is provided to them it is also creating sustainable & durable assets in the village. The scheme has given a power to the daily wage laborers to fight for their right to receive that they must receive & it is also an opportunity to promote overall development & to give the power to the rural society of our country. MGNREGA is a land mark legislation in the Indian history of social security legislation after independence. This legislation has been bringing about a silent revolution in rural areas. The MGNREGA is India's first law to codify development rights in a legal framework. There is a long & immediate need to formulate rules to operationalise provisions in the act which included guaranteeing grievance redressal in 7 days, social audit twice a year & mandatory transparency & proactive disclosure. National Rural Employment Guarantee Act was passed by parliament & enacted on 5th December 2005. The NREGA scheme was initially came in to force in 200 districts of 27 states in phase 1 (one). It is firstly launched in Anantpur district of Andhra Pradesh on 2nd February 2006 by our Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh. It was implemented in three phases & covered the whole country within 5 years. This act provides Right Based Employment to the rural people of India. On 31st December 2009 the act was renamed by an amendment as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005. 2 The implementation of NREGA largely depends on the active participation of 3 tier decentralized self governance and Panchayat institutions. -

Government of West Bengal Public Works Department Writers Buildings Kolkata 700 001

Government of West Bengal Public Works Department Writers Buildings Kolkata 700 001 The Following allotments in Banga Bhavan, 3,Halley Road, New Delhi are hereby made Booking Date: 2011-07-13 Allotee's Arrival Dt / Charges / Paid Sl No Memo No Designation Room No Category Name Departure Dt Day Status Arrival Date: 2011-07-12 006192CS(BB) 601 Full 12/07/2011 M 1 Sri Asit Mal MLA, WB A9 100.00 No 13/07/2011 Room 13/07/2011 M Arrival Date: 2011-07-13 006187CS(BB) C/o. Dr.A.K.Palit, 13/07/2011 M 2 Sri Soumyajit Mallick 206 1 Bed F1 300.00 No 13/07/2011 Assoc.Prof.SSKMH 13/07/2011 E 006247CS(BB) Sri Ranjeet Mondal & 601 Full 13/07/2011 E 3 MLA, WBLA A9 100.00 No 13/07/2011 Companion Room 17/07/2011 E 006244CS(BB) 13/07/2011 E 4 Sri Ashis Majumder CE. KMW&SA 503 1 Bed A11 50.00 No 13/07/2011 14/07/2011 M 006244CS(BB) 13/07/2011 E 5 Sri B.Mukherjee — 503 1 Bed A11 50.00 No 13/07/2011 14/07/2011 M 006192CS(BB) 109 Full 13/07/2011 M 6 Sri Asit Mal — A9 100.00 No 13/07/2011 Room 14/07/2011 E 006187CS(BB) 13/07/2011 E 7 Sri Soumyajit Mallick — 204 1 Bed F1 300.00 No 13/07/2011 14/07/2011 E Arrival Date: 2011-07-14 006251CS(BB) 103 Full 14/07/2011 M 8 Sri Samar Mukherjee MLA, WB A9 100.00 No 13/07/2011 Room 20/07/2011 E 006250CS(BB) C/o. -

A Case for Change in Indian Historic Preservation Planning: Re-Evaluating Attitudes Toward the Past

University of Cincinnati Date: 1/6/2010 I, Kingkini Roy , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture in Architecture. It is entitled: A Case for Change in Indian Historic Preservation Planning: Re-Evaluating Attitudes toward the Past Student's name: Kingkini Roy This work and its defense approved by: Committee chair: Patrick Snadon, PhD Committee member: Aarati Kanekar, PhD 1280 Last Printed:2/15/2011 Document Of Defense Form A Case for Change in Indian Historic Preservation Planning: Re-Evaluating Attitudes toward the Past A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture In the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning March 2011 by Kingkini Roy Bachelor of Architecture, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, 2006 Committee Chair: Patrick Snadon, Ph. D. Abstract This thesis critically surveys heritage management in present day India and the legislative apparatus that underpins it. Keeping within the Indian context, the research seeks to verify the suitability of the strategies that are upheld by the institutional and legislative setup of architectural conservation practices for present day India. This appraisal would be based on the premise that preservation, as it is currently understood in India, is a product of modernity and in India’s case the direct import of the Western construct of these disciplines during the colonial period. This is made evident from the history and origins of the interest in Indian antiquity as well as the development of the formalized discipline of archaeology and antiquity management. -

Issn 2319 – 9202

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF COMMERCE, ARTS AND SCIENCE ISSN 2319 – 9202 An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust WWW.CASIRJ.COM www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions CASIRJ Volume 10 Issue 6 [Year - 2019] ISSN 2319 – 9202 EMPLOYMENT GENERATION THROUGH MGNREGA IN MEGHALAYA Happy Sutnga, Dr. Gita Pyal Research Scholar, Dept. of. Sociology, William Carey University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India Research Supervisor, Dept. of. Sociology, William Carey University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India Email: [email protected] Abstract The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is Primarily Enacted to provide hundred Days of Guaranteed Employment in a Year to Rural Households on Demand Basis and Creation of Durable Assets to Strengthen Rural Livelihood Resource Base. Studies Based on Empirical Evidences Indicate Mixed Outcome in Terms of Employment Generation and Durability and Usefulness of the Assets Created. the Act Stresses upon Identification, Planning, Execution and Monitoring of Projects in a Participatory Manner with a View to Deepening Democracy. Gram Panchayats (GPS) are assigned with the Responsibility of formulating the Works. The Present Study Attempts to Extent of employment generation through NREGA in Meghalaya. Keywords: NREGA, job, Introduction National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (or, NREGA No 42, later renamed as the "Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act", MGNREGA), is an Indian labour law and social security measure that aims to guarantee the 'right to work'. It aims to enhance livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of wage employment in a financial year to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.[1][2] The act was first proposed in 1991 by P.V. -

Self-Study Report

Presidency University Self-Study RepoRt For Submission to the National Assessment and Accreditation Council Presidency University Kolkata 2016 (www.presiuniv.ac.in) Volume-1 Self-Study Report (Volume-1) Institutional Data Analysis 1 Presidency University 2 Self-Study Report (Volume-1) Self-Study RepoRt For Submission to the National Assessment and Accreditation Council Presidency University Kolkata 2016 (www.presiuniv.ac.in) Volume-1 (Institutional Data Analysis) Foreword I am delighted to present the Self-Study Report of Presidency University for the first cycle of accreditation by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council. We were upgraded from Presidency College to Presidency University in 2010. The First Vice-Chancellor was appointed in 2011. The faculty were subsequently recruited from mid-2012. Our Statutes were published on July 7th 2014. The first batch of undergraduate students were admitted in July 2011 and they graduated in June 2014. The first batch of postgraduate students graduated in June 2013. We began our PhD programme in 2015. As Presidency College, we received a NAAC accreditation at the A+ level with an institutional score of 90.95. The history of our glorious institution extends from 1817 when we started as the Hindoo College. It has been a challenge, where we believe, we have succeeded in upgrading our infrastructure, facilities and curriculum for transforming this prestigious undergraduate college to a modern university at par with the best in the country within a short span of five years. While upgrading our teaching and research programmes to those of a modern university, we have incorporated the liberal arts and sciences in choice-based GenEd courses.