The Mitochondrial Genome of the Lycophyte Huperzia Squarrosa: the Most Archaic Form in Vascular Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cycad Aulacaspis Scale

Invasive Insects: Risks and Pathways Project CYCAD AULACASPIS SCALE UPDATED: APRIL 2020 Invasive insects are a huge biosecurity challenge. We profile some of the most harmful insect invaders overseas to show why we must keep them out of Australia. Species Cycad aulacaspis scale / Aulacaspis yasumatsui. Also known as Asian cycad scale. Main impacts Decimates wild cycad populations, kills cultivated cycads. Native range Thailand. Invasive range China, Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia, Guam, United States, Caribbean Islands, Mexico, France, Ivory Coast1,2. Detected in New Zealand in 2004, but eradicated.2 Main pathways of global spread As a contaminant of traded nursery material (cycads and cycad foliage).3 WHAT TO LOOK OUT FOR The adult female cycad aulacaspis scale has a white cover (scale), 1.2–1.6 mm long, ENVIRONMENTAL variable in shape and sometimes translucent enough to see the orange insect with its IMPACTS OVERSEAS orange eggs beneath. The scale of the male is white and elongate, 0.5–0.6 mm long. Photo: Jeffrey W. Lotz, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, The cycad aulacaspis scale has decimated Bugwood.org | CC BY 3.0 cycads on Guam since it appeared there in 2003. The affected species, Cycas micronesica, was once the most common cause cycad extinctions around the world, Taiwan, 100,000 cycads were destroyed tree on Guam, but was listed by the IUCN 7 including in India10 and Indonesia11. The by an outbreak of the scale . It is difficult as endangered in 2006 following attacks continuous removal of plant sap by the to control in cultivation because of high by three insect pests, of which this scale scale depletes cycads of carbohydrates4,9. -

Evolution and Comparative Morphology of the Euglenophyte

EVOLUTION AND COMPARATIVE MORPHOLOGY OF THE EUGLENOPHYTE PLASTID by PATRICK JERRY PAUL BROWN (Under the Direction of Mark A. Farmer) ABSTRACT My doctoral research centered on understanding the evolution of the euglenophyte protists, with special attention paid to their plastids. The euglenophytes are a widely distributed group of euglenid protists that have acquired a chloroplast via secondary symbiogenesis. The goals of my research were to 1) test the efficacy of plastid morphological and ultrastructural characters in phylogenetic analysis; 2) understand the process of plastid development and partitioning in the euglenophytes; 3) to use a plastid- encoded protein gene to determine a euglenophyte phylogeny; and 4) to perform a multi- gene analysis to uncover clues about the origins of the euglenophyte plastid. My work began with an alpha-taxonomic study that redefined the rare euglenophyte Euglena rustica. This work not only validly circumscribed the species, but also noted novel features of its habitat, cyclic migration habits, and cellular biology. This was followed by a study of plastid morphology and development in a number of diverse euglenophytes. The results of this study showed that the plastids of euglenophytes undergo drastic changes in morphology and ultrastructure over the course of a single cell division cycle. I concluded that there are four main classes of plastid development and partitioning in the euglenophytes, and that the class a given species will use is dependant on its interphase plastid morphology and the rigidity of the cell. The discovery of the class IV partitioning strategy in which cells with only one or very few plastids fragment their plastids prior to cell division was very significant. -

35 Ideal Landscape Cycads

3535 IdealIdeal LandscapeLandscape CycadsCycads Conserve Cycads by Growing Them -- Preservation Through Propagation Select Your Plant Based on these Features: Exposure: SunSun ShadeShade ☻☻ ColdCold☻☻ Filtered/CoastalFiltered/Coastal SunSun ▲▲ Leaf Length and Spread: Compact, Medium or Large? Growth Rate and Ultimate Plant Size Climate: Subtropical, Mediterranean, Temperate? Dry or Moist? Leaves -- Straight or Arching? Ocean-Loving, Salt-Tolerant, Wind-Tolerant CeratozamiaCeratozamiaCeratozamiaCeratozamia SpeciesSpeciesSpeciesSpecies ☻Shade Loving ☻Cold TolerTolerantant ▲Filtered/Coastal Sun 16 named + several undescribed species Native to Mexico, Guatemala & Belize Name originates from Greek ceratos (horned), and azaniae, (pine cone) Pinnate (feather-shaped) leaves, lacking a midrib, and horned, spiny cones Shiny, darker green leaves arching or upright, often emerging red or brown Less “formal” looking than other cycads Prefer Shade ½ - ¾ day, or afternoon shade Generally cold-tolerant CeratozamiaCeratozamia ---- SuggestedSuggested SpeciesSpecies ☻Shade Loving ☻Cold TolerTolerantant ▲Filtered/Coastal Sun Ceratozamia mexicana Tropical looking but cold-tolerant, native to dry mountainous areas in the Sierra Madre Mountains (Mexican Rockies). Landscape specimen works well with water features, due to arching habit. Prefers shade, modest height, with a spread of up to 10 feet. Trunk grows to 2 feet tall. Leaflets can be narrow or wider (0.75-2 inches). CeratozamiaCeratozamia ---- SuggestedSuggested SpeciesSpecies ☻Shade Loving ☻Cold TolerTolerantant ▲Filtered/Coastal Sun Ceratozamia latifolia Rare Ceratozamia named for its broad leaflets. Native to cloud forests of the Sierra Madre mountains of Mexico, underneath oak trees. Emergent trunk grows to 1 foot tall, 8 inches in diameter. New leaves emerge bronze, red or chocolate brown, hardening off to bright green, semiglossy, and grow to 6 feet long. They are flat lance-shaped, asymmetric, and are broadest above middle, growing to 10 inches long and 2 inches wide. -

Lateral Gene Transfer of Anion-Conducting Channelrhodopsins Between Green Algae and Giant Viruses

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042127; this version posted April 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 5 Lateral gene transfer of anion-conducting channelrhodopsins between green algae and giant viruses Andrey Rozenberg 1,5, Johannes Oppermann 2,5, Jonas Wietek 2,3, Rodrigo Gaston Fernandez Lahore 2, Ruth-Anne Sandaa 4, Gunnar Bratbak 4, Peter Hegemann 2,6, and Oded 10 Béjà 1,6 1Faculty of Biology, Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel. 2Institute for Biology, Experimental Biophysics, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Invalidenstraße 42, Berlin 10115, Germany. 3Present address: Department of Neurobiology, Weizmann 15 Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel. 4Department of Biological Sciences, University of Bergen, N-5020 Bergen, Norway. 5These authors contributed equally: Andrey Rozenberg, Johannes Oppermann. 6These authors jointly supervised this work: Peter Hegemann, Oded Béjà. e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] 20 ABSTRACT Channelrhodopsins (ChRs) are algal light-gated ion channels widely used as optogenetic tools for manipulating neuronal activity 1,2. Four ChR families are currently known. Green algal 3–5 and cryptophyte 6 cation-conducting ChRs (CCRs), cryptophyte anion-conducting ChRs (ACRs) 7, and the MerMAID ChRs 8. Here we 25 report the discovery of a new family of phylogenetically distinct ChRs encoded by marine giant viruses and acquired from their unicellular green algal prasinophyte hosts. -

Neoproterozoic Origin and Multiple Transitions to Macroscopic Growth in Green Seaweeds

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/668475; this version posted June 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Neoproterozoic origin and multiple transitions to macroscopic growth in green seaweeds Andrea Del Cortonaa,b,c,d,1, Christopher J. Jacksone, François Bucchinib,c, Michiel Van Belb,c, Sofie D’hondta, Pavel Škaloudf, Charles F. Delwicheg, Andrew H. Knollh, John A. Raveni,j,k, Heroen Verbruggene, Klaas Vandepoeleb,c,d,1,2, Olivier De Clercka,1,2 Frederik Leliaerta,l,1,2 aDepartment of Biology, Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281, 9000 Ghent, Belgium bDepartment of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, Technologiepark 71, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium cVIB Center for Plant Systems Biology, Technologiepark 71, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium dBioinformatics Institute Ghent, Ghent University, Technologiepark 71, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium eSchool of Biosciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia fDepartment of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Benátská 2, CZ-12800 Prague 2, Czech Republic gDepartment of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA hDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138, USA. iDivision of Plant Sciences, University of Dundee at the James Hutton Institute, Dundee, DD2 5DA, UK jSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia (M048), 35 Stirling Highway, WA 6009, Australia kClimate Change Cluster, University of Technology, Ultimo, NSW 2006, Australia lMeise Botanic Garden, Nieuwelaan 38, 1860 Meise, Belgium 1To whom correspondence may be addressed. Email [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] or [email protected]. -

Cycad Aulacaspis Scale

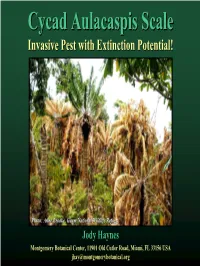

CycadCycad AulacaspisAulacaspis ScaleScale InvasiveInvasive PestPest withwith ExtinctionExtinction Potential!Potential! Photo: Anne Brooke, Guam National Wildlife Refuge Jody Haynes Montgomery Botanical Center, 11901 Old Cutler Road, Miami, FL 33156 USA [email protected] GeneralGeneral CycadCycad InformationInformation OrderOrder:: CycadalesCycadales FamiliesFamilies:: BoweniaceaeBoweniaceae,, Cycadaceae,Cycadaceae, Stangeriaceae,Stangeriaceae, ZamiaceaeZamiaceae ExtantExtant speciesspecies:: 302302 currentlycurrently recognizedrecognized Photo: Dennis Stevenson DistributionDistribution:: PantropicalPantropical ConservationConservation statusstatus:: CycadsCycads representrepresent oneone ofof thethe mostmost threatenedthreatened plantplant groupsgroups worldwide;worldwide; >50%>50% listedlisted asas threatenedthreatened oror endangeredendangered Photo: Tom Broome Photo: Mark Bonta AulacaspisAulacaspis yasumatsuiyasumatsui TakagiTakagi OrderOrder:: Hemiptera/HomopteraHemiptera/Homoptera FamilyFamily:: DiaspididaeDiaspididae CommonCommon namesnames:: OfficialOfficial cycadcycad aulacaspisaulacaspis scalescale (CAS)(CAS) OtherOther AsianAsian cycadcycad scale,scale, ThaiThai scale,scale, snowsnow scalescale NativeNative distributiondistribution:: AndamanAndaman IslandsIslands toto Vietnam,Vietnam, W. Tang, USDA-APHIS-PPQ includingincluding ThailandThailand andand probablyprobably Cambodia,Cambodia, Laos,Laos, peninsularpeninsular Malaysia,Malaysia, Myanmar,Myanmar, southernmostsouthernmost China,China, andand possiblypossibly -

Aulacaspis Yasumatsui Takagi

Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi The Cycad Aulacaspis Scale (CAS), Aulacaspis yasumatsui, a native of Southeast Asia, is found on plants from the gymnosperm order Cycadales. Its preferred host belong to the genus Cycas. CAS is highly damaging to cycads, which include horticulturally important and endangered plant species. The scale has the potential to spread to new areas via plant movement in the horticulture trade. Its known introduced range includes some states in the USA including Florida and Hawai‘i, Cayman Is. Puerto Rico and Vieques Islands, US Virgin Islands, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Guam. CAS has been reported from the island of Rota (Northern Mariana Islands) in 2007 and Palau in 2008. or at the base of the petiole. Scales also infest the upper surfaces Infestations of CAS on cycads begin on the undersides of leaflets The leaves of infested cycads have a whitewashed appearance. Infestedof leaflets plants eventually, will typically and thehave terminal chlorotic, portion yellow-brown of the leaves,cycad. as the continuous removal of plant sap by the scale will usually Photo credit: Anne Brooke result in the death of the leaves (Weissling, 1999; Heu et al. 2003). By May 2005 it was estimated that half the king sago palms were CAS has been reported in the Taitung Cycad Nature Reserve, killed and population numbers of fadang were said to be declining Taiwan, home of the endemic prince sago the ‘Vulnerable (VU)’ (Haynes and Marler, 2005). Cycas taitungensis Besides the use of insecticides, the lady beetle, Rhyzobius lophanthae 2003, on the ‘Near Threatened (NT)’ king sago palms Cycas (Blaisdell) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), has been used as a biological . -

Newcastle University Eprints

Newcastle University ePrints Civan P, Foster PG, Embley MT, Seneca A, Cox CJ. Analyses of Charophyte Chloroplast Genomes Help Characterize the Ancestral Chloroplast Genome of Land Plants. Genome Biology and Evolution 2014, 6(4), 897-911. Copyright: © The Author(s) 2014. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non- Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact [email protected] DOI link to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evu061 Further information on publisher website: http://gbe.oxfordjournals.org/ Date deposited: 30th May 2014 Version of article: Published This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License ePrints – Newcastle University ePrints http://eprint.ncl.ac.uk GBE Analyses of Charophyte Chloroplast Genomes Help Characterize the Ancestral Chloroplast Genome of Land Plants Peter Civa´nˇ 1, Peter G. Foster2,MartinT.Embley3,AnaSe´neca4,5,andCymonJ.Cox1,* 1Centro de Cieˆncias do Mar, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal 2Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom 3Institute for Cell and Molecular Biosciences, University of Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom 4Department of Biology, Faculdade de Cieˆncias da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal 5Department of Biology, Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Universitet, Trondheim, Norway *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted: March 23, 2014 Downloaded from Data deposition: The chloroplast genome sequences reported in this article have been deposited in GenBank under the accessions Klebsormidium flaccidum KJ461680, Mesotaenium endlicherianum KJ461681, and Roya anglica KJ461682. -

Investigations Into Encephalartos Insect Pests and Diseases in South Africa Identifies Phytophthora Cinnamomi As a Pathogen of the Modjadji Cycad

Investigations into Encephalartos insect pests and diseases in South Africa identifies Phytophthora cinnamomi as a pathogen of the Modjadji cycad R. Nesamari1, T.A. Coutinho1 and J. Roux 2* 1Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, DST & NRF Centre of Excellence in Tree Health Biotechnology (CTHB), Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield, Pretoria, 0028 South Africa 2Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, CTHB, FABI, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa * Email corresponding author: [email protected] South Africa holds the greatest diversity of Encephalartos species globally. I In recent years several reports have been received of Encephalartos species in the country dying of unknown causes. The aim of this study was to investigate the presence of, and identify the causal agents of diseases of Encephalartos species in the Gauteng and Limpopo Provinces of South Africa. Symptomatic plant material and insects were collected from diseased plants in private gardens, commercial nurseries and conservation areas in these regions. Insects collected were identified based on morphology, and microbial isolates based on morphology and DNA sequence data. Insect species identified infesting cultivated cycads included the beetle Amorphocerus talpa, and the scale insects, Aonidiella aurantii, Aspidiotus capensis, Chrysomphalus aonidum, Lindingaspis rossi, Pseudaulacaspis cockerelli, Pseudaulacaspis pentagona and Pseudococcus longispinus. Fungal species isolated from diseased plants included species of Diaporthe, Epicoccum, Fusarium, Lasiodiplodia, Neofusicoccum, Peyronellaea, Phoma, Pseudocercospora and 1 Toxicocladosporium. The plant pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi was identified from E. transvenosus plants in the Modjadji Nature Reserve. Artificial inoculation studies fulfilled Koch‟s postulates, strongly suggesting that P. -

An Unrecognized Ancient Lineage of Green Plants Persists in Deep Marine Waters

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Notice: ©2010 Phycological Society of America. This manuscript is an author version with the final publication available at http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/ and may be cited as: Zechman, F. W., Verbruggen, H., Leliaert, F., Ashworth, M., Buchheim, M. A., Fawley, M. W., Spalding, H., Pueschel, C. M., Buchheim, J. A., Verghese, B., & Hanisak, M. D. (2010). An unrecognized ancient lineage of green plants persists in deep marine waters. Journal of Phycology, 46(6), 1288‐1295. (Suppl. material). doi:10.1111/j.1529‐8817.2010.00900.x J. Phycol. 46, 1288–1295 (2010) Ó 2010 Phycological Society of America DOI: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00900.x AN UNRECOGNIZED ANCIENT LINEAGE OF GREEN PLANTS PERSISTS IN DEEP MARINE WATERS1 Frederick W. Zechman2,3 Department of Biology, California State University Fresno, 2555 East San Ramon Ave, Fresno, California 93740, USA Heroen Verbruggen,3 Frederik Leliaert Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281 S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium Matt Ashworth University Station MS A6700, 311 Biological Laboratories, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, USA Mark A. Buchheim Department of Biological Science, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma 74104, USA Marvin W. Fawley School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences, University of Arkansas at Monticello, Monticello, Arkansas 71656, USA Department of Biological Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota 58105, USA Heather Spalding Botany Department, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA Curt M. Pueschel Department of Biological Sciences, State University of New York at Binghamton, Binghamton, New York 13901, USA Julie A. -

The Chloroplast and Mitochondrial Genome Sequences of The

The chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences of the charophyte Chaetosphaeridium globosum: Insights into the timing of the events that restructured organelle DNAs within the green algal lineage that led to land plants Monique Turmel*, Christian Otis, and Claude Lemieux Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Program in Evolutionary Biology, and De´partement de Biochimie et de Microbiologie, Universite´Laval, Que´bec, QC, Canada G1K 7P4 Edited by Jeffrey D. Palmer, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, and approved June 19, 2002 (received for review April 5, 2002) The land plants and their immediate green algal ancestors, the organelle DNAs (mainly for the cpDNA of Spirogyra maxima,a charophytes, form the Streptophyta. There is evidence that both member of the Zygnematales; refs. 11–13), it is difficult to predict the chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) the timing of the major events that shaped the architectures of underwent substantial changes in their architecture (intron inser- land-plant cpDNAs and mtDNAs. tions, gene losses, scrambling in gene order, and genome expan- Mesostigma cpDNA is highly similar in size and gene organization sion in the case of mtDNA) during the evolution of streptophytes; to the cpDNAs of the 10 photosynthetic land plants examined thus however, because no charophyte organelle DNAs have been se- far (the bryophyte Marchantia polymorpha and nine vascular plants; quenced completely thus far, the suite of events that shaped see www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov͞PMGifs͞Genomes͞organelles.html), streptophyte organelle genomes remains largely unknown. Here, but lacks any introns and contains Ϸ20 extra genes (7). Chloroplast we have determined the complete cpDNA (131,183 bp) and mtDNA gene loss is an ongoing process in the Streptophyta, with indepen- (56,574 bp) sequences of the charophyte Chaetosphaeridium glo- dent losses occurring in multiple lineages (14, 15). -

Seta Structure in Members of the Coleochaetales (Streptophyta)

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-23-2015 Seta Structure In Members Of The Coleochaetales (streptophyta) Timothy Richard Rockwell Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Rockwell, Timothy Richard, "Seta Structure In Members Of The Coleochaetales (streptophyta)" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 376. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/376 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SETA STRUCTURE IN MEMBERS OF THE COLEOCHAETALES (STREPTOPHYTA) Timothy R. Rockwell 28 Pages May 2015 The charophycean green algae, which include the Coleochaetales, together with land plants form a monophyletic group, the streptophytes. The order Coleochaetales, a possible sister taxon to land plants, is defined by its distinguishing setae (hairs), which are encompassed by a collar. Previous studies of these setae yielded conflicting results and were confined to one species, Coleochaet. scutata. In order to interpret these results and learn about the evolution of this character, setae of four species of Coleochaete and the genus Chaetosphaeridium within the Coleochaetales were studied to determine whether cellulose, callose, and phenolic compounds contribute to the chemical composition of the setae. Two major differences were found in the complex hairs of the two genera. In Chaetosphaeridium the entire seta collar stained with calcofluor indicating the presence of cellulose, while in the four species of Coleochaete only the base of the seta collar stained with calcofluor.