The End of the Myth of a Brotherly Belarus?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minsk II a Fragile Ceasefire

Briefing 16 July 2015 Ukraine: Follow-up of Minsk II A fragile ceasefire SUMMARY Four months after leaders from France, Germany, Ukraine and Russia reached a 13-point 'Package of measures for the implementation of the Minsk agreements' ('Minsk II') on 12 February 2015, the ceasefire is crumbling. The pressure on Kyiv to contribute to a de-escalation and comply with Minsk II continues to grow. While Moscow still denies accusations that there are Russian soldiers in eastern Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly admitted in March 2015 to having invaded Crimea. There is mounting evidence that Moscow continues to play an active military role in eastern Ukraine. The multidimensional conflict is eroding the country's stability on all fronts. While the situation on both the military and the economic front is acute, the country is under pressure to conduct wide-reaching reforms to meet its international obligations. In addition, Russia is challenging Ukraine's identity as a sovereign nation state with a wide range of disinformation tools. Against this backdrop, the international community and the EU are under increasing pressure to react. In the following pages, the current status of the Minsk II agreement is assessed and other recent key developments in Ukraine and beyond examined. This briefing brings up to date that of 16 March 2015, 'Ukraine after Minsk II: the next level – Hybrid responses to hybrid threats?'. In this briefing: • Minsk II – still standing on the ground? • Security-related implications of the crisis • Russian disinformation -

2008 Hate Crime Survey

2008 Hate Crime Survey About Human Rights First HRF’s Fighting Discrimination Program Human Rights First believes that building respect for human The Fighting Discrimination Program has been working since rights and the rule of law will help ensure the dignity to which 2002 to reverse the rising tide of antisemitic, racist, anti- every individual is entitled and will stem tyranny, extremism, Muslim, anti-immigrant, and homophobic violence and other intolerance, and violence. bias crime in Europe, the Russian Federation, and North America. We report on the reality of violence driven by Human Rights First protects people at risk: refugees who flee discrimination, and work to strengthen the response of persecution, victims of crimes against humanity or other mass governments to combat this violence. We advance concrete, human rights violations, victims of discrimination, those whose practical recommendations to improve hate crimes legislation rights are eroded in the name of national security, and human and its implementation, monitoring and public reporting, the rights advocates who are targeted for defending the rights of training of police and prosecutors, the work of official anti- others. These groups are often the first victims of societal discrimination bodies, and the capacity of civil society instability and breakdown; their treatment is a harbinger of organizations and international institutions to combat violent wider-scale repression. Human Rights First works to prevent hate crimes. For more information on the program, visit violations against these groups and to seek justice and www.humanrightsfirst.org/discrimination or email accountability for violations against them. [email protected]. Human Rights First is practical and effective. -

Military Cooperation Between Russia and Belarus: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives

ISSN 2335-870X LITHUANIAN ANNUAL STRATEGIC REVIEW 2019 Volume 17 231 Virgilijus Pugačiauskas* General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania Military Cooperation between Russia and Belarus: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives The article analyses the dynamics of military cooperation between Russia and Belarus at the time when Russia’s aggression against Ukraine revealed president Vladimir Putin’s objective to consolidate control over his interest zone in the nearest post-soviet area at all hazards. This could be called the time-period during which endurance of military cooperation is increased and during which Rus- sia demonstrates its principle ambition to expand the use of military capabilities while leaning on Belorussian military capabilities, military infrastructure and territory as a bridgehead for potential military actions. For this reason, the aim of the paper is to outline the key factors which determine military integration of the both countries, or, more specifically, to discuss orientations and objectives set forth for building military cooperation as laid down in the documents regulating military policy, to discuss and assess practical cases of strengthening of interaction between military capabilities (stra- tegic military exercises), to reveal the accomplishments of military and technical cooperation, prob- lems it might pose and potential prospects of its development. Introduction In the relationship between Belarus and Russia, the field of military co- operation could be highlighted as the most stable over the past three decades, though the relationship of the both countries is accompanied by alleged, sta- ged and still emerging disagreements or flashes of short-term tension which notably remind of movement of meteors, which illuminate the sky, towards the sinful planet of Earth. -

Peacekeepers in the Donbas JFQ 91, 4Th Quarter 2017 12 India to Lead the Mission

Eastern Ukrainian woman, one of over 1 million internally displaced persons due to conflict, has just returned from her destroyed home holding all her possessions, on main street in Nikishino Village, March 1, 2015 (© UNHCR/Andrew McConnell) cal ploy; they have suggested calling Putin’s bluff. However, they also realize Peacekeepers the idea of a properly structured force with a clear mandate operating in support of an accepted peace agreement in the Donbas could offer a viable path to peace that is worth exploring.2 By Michael P. Wagner Putin envisions a limited deploy- ment of peacekeepers on the existing line of contact in Donbas to safeguard OSCE-SMM personnel.3 Such a plan ince the conflict in Ukraine September 5, 2017, when he proposed could be effective in ending the conflict began in 2014, over 10,000 introducing peacekeepers into Eastern and relieving immediate suffering, but it people have died in the fighting Ukraine to protect the Organiza- S could also lead to an open-ended United between Russian-backed separatists tion for Security and Co-operation in Nations (UN) commitment and make and Ukrainian forces in the Donbas Europe–Special Monitoring Mission long-term resolution more challenging. region of Eastern Ukraine. The Ukrai- to Ukraine (OSCE-SMM). Despite Most importantly, freezing the conflict nian government has repeatedly called halting progress since that time, restart- in its current state would solidify Russian for a peacekeeping mission to halt ing a peacekeeping mission remains an control of the separatist regions, enabling the bloodshed, so Russian President important opportunity.1 Many experts it to maintain pressure on Ukraine by Vladimir Putin surprised the world on remain wary and dismiss it as a politi- adjusting the intensity level as it de- sires. -

UNHCR Comments on the Draft Amendments to the Law on Citizenship of Belarus

UNHCR Comments on the draft Amendments to the Law on Citizenship of Belarus A. Introduction In October 2019, at the High-Level Segment on Statelessness convened by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as part of its 70th Executive Committee meeting, Belarus pledged to accede to the two UN Statelessness Conventions – the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons (hereinafter referred to as ‘1954 Convention’) and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness (hereinafter referred to as ‘1961 Convention’) – by the end of 2020 after completion of all necessary internal procedures. UNHCR very much welcomes this commitment by the Government of the Republic of Belarus. In July 2020, the Department on Citizenship and Migration of the Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Belarus, the central authority in charge of citizenship and statelessness issues, reaffirmed Belarus’ intention to ratify the 1954 and 1961 Conventions by the end of 2020. UNHCR was also informed that before the ratification of both UN Statelessness Conventions, amendments would be made to the Law of the Republic of Belarus dated 01.09.2002 No. 136-З “On citizenship of the Republic of Belarus” (edition dated 20.07.2016 No. 414-З) (hereinafter referred to as ‘Law on Citizenship’). In July 2020, the House of Representatives of the National Assembly of the Republic of Belarus (hereinafter referred to as ‘House of Representatives’) informed the UNHCR Representation in Belarus that on 4 June 2020 it has adopted, in the first hearing, the draft Law of the Republic of Belarus “On amendments to the Law on the Republic of Belarus “On citizenship of the Republic of Belarus”. -

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Contemporary Recordings of Belarusian Folk Biblical and Non-Biblical Etiological Legends in the Comparative-Historical Aspect

https://doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2018.72.boganeva CONTEMPORARY RECORDINGS OF BELARUSIAN FOLK BIBLICAL AND NON-BIBLICAL ETIOLOGICAL LEGENDS IN THE COMPARATIVE-HISTORICAL ASPECT Elena Boganeva Center for Belarusian Culture, Language and Literature Research National Academy of Sciences, Belarus e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The article considers some rare etiologies in contemporary record- ings – non-biblical cosmogonic and folk biblical anthropogenic etiologies in the comparative and historical aspect. Cosmogonic etiologies are stories about the predetermination of spatial and temporal parameters of the world (texts about the origins of the elements of the earthscape, in particular, mountains; about the agreement made between God and Satan concerning the distribution of as- cendancy over people at the beginning of the world and at the end of it; about the determination of the time of the existence of the world and the change of time); about the structure of the current status of the Universe (the Earth is round, it revolves and is supported by a giant turtle or tortoise); about the primary entity or body, from which the following emerges: the world (out of a child’s body), a part of cultural space – a group of inhabited localities (out of a felled statue), and one of the primary elements – fire (out of a human). Anthropogenic folk biblical etiologies include stories about the origins of sexual relations between the first people (two versions); the birth of children out of different body parts (the head, through the side of the body); and the origins of hair on male bodies. Keywords: anthropogenic etiologies, etiological legend, etiologies of cosmogonic legends, folk Bible, folk biblical etiologies, folk narratives, non-biblical etiologies, vernacular Christianity INTRODUCTION According to its administrative division, there are 6 regions (oblasts) and 118 districts in Belarus. -

Яюm I C R O S O F T W O R

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS 2004 ANNUAL REPORT Minsk 2005 C O N T E N T S INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW /2 STATISTICAL BACKGROUND /3 CHANGES IN THE LEGISLATION /5 INFRINGEMENTS OF RIGHTS OF MASS-MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS, CONFLICTS IN THE SPHERE OF MASS-MEDIA Criminal cases for publications in mass-media /13 Encroachments on journalists and media /16 Termination or suspension of mass-media by authorities /21 Detentions of journalists, summoning journalists to law enforcement bodies. Warnings of the Office of Public Prosecutor /29 Censorship. Interference in professional independence of editions /35 Infringements related to access to information (refusals in granting information, restrictive use of institute of accreditation) /40 The conflicts related to reception and dissemination of foreign information or activity of foreign mass-media /47 Economic policy in the sphere of mass-media /53 Restriction of the right on founding mass-media /57 Interference with production of mass-media /59 Hindrance to distribution of mass-media production /62 SENSATIONAL CASES The most significant litigations with participation of mass-media and journalists /70 Dmitry Zavadsky's case /79 Belarusian periodic printed editions mentioned in the monitoring /81 1 INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW The year 2004 for Belarus was the year of parliamentary elections and the referendum. As usual during significant political campaigns, the pressure on mass-media has increased in 2004. The deterioration of the media situation was not a temporary deviation after which everything usually comes back to normal, but represented strengthening of systematic and regular pressure upon mass- media, which continued after the election campaign. -

Regime and Churches: What Is Therebetween? Religion In

Issue 8 (38), 2013 RELIGION IN BELARUS: LIMITED INDEPENDENCE Since the concept of secular state has become a issue of “The Bell” is dedicated to answer these standard in a Western world long time ago, the questions. position of the Church is not very much discussed while speaking about the political issues. How- In the first article Anton Radniankou analyses the ever, there are tendencies of the rising interest of three biggest confessions in Belarus and reveals the Putin’s regime on involving Russian Orthodox their connection with the regime. He states, that Church to strengthening its power. while the Orthodox Church is the most familiar Anton Radniankou is a project to the government, Protestants are the least loyal manager of the Local Foundation And we might find similar approach of the Belar- to A.Lukashenka. “Interakcia”. He also edits intellec- usian regime. A.Lukashenka calls the Orthodox tual online magazine IdeaBY. Church as the main ideologist of the statehood, In the second article Natallia Vasilevich takes while remaining a non-believer – some kind of a deeper look into relations between Orthodox Natallia Vasilevich is a politi- strange “Orthodox atheist” composition. More- Church and the regime. She finds out that there cal scientist, lawyer and theolo- over, the Russian Orthodox Church authorities are different groups among the Church branches, gian. She is director of Centre have a direct influence on the Belarusian Church, which position ranges from pro-Russian to pro- “Ecumena” and editor of website forming its shape and ideology. It is clear that Nationalist wings. All in all, it is mostly influ- “Carkwa”. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

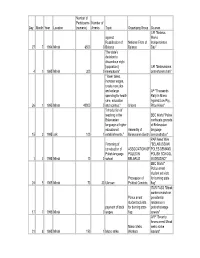

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

NARRATING the NATIONAL FUTURE: the COSSACKS in UKRAINIAN and RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK a DISSERTATION Prese

NARRATING THE NATIONAL FUTURE: THE COSSACKS IN UKRAINIAN AND RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Comparative Literature and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anna Kovalchuk Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Katya Hokanson Chairperson Michael Allan Core Member Serhii Plokhii Core Member Jenifer Presto Core Member Julie Hessler Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Anna Kovalchuk iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Anna Kovalchuk Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature June 2017 Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation investigates nineteenth-century narrative representations of the Cossacks—multi-ethnic warrior communities from the historical borderlands of empire, known for military strength, pillage, and revelry—as contested historical figures in modern identity politics. Rather than projecting today’s political borders into the past and proceeding from the claim that the Cossacks are either Russian or Ukrainian, this comparative project analyzes the nineteenth-century narratives that transform pre- national Cossack history into national patrimony. Following the Romantic era debates about national identity in the Russian empire, during which the Cossacks become part of both Ukrainian and Russian national self-definition, this dissertation focuses on the role of historical narrative in these burgeoning political projects.