Hunks, Hotties, and Pretty Boys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosalyn Drexler at Mitchell Algus Ans Nicholas Davies

bringing hard-edged , often ro lent imagery from film noir alll tabloid culture into the Poi arena. Known also as a plat wright and novelist , Drexler r her youth enjoyed a brief stintas , a professional wrestler. Ths dual -ven ue selection of bol '60s work and recent painting! and collages more than proves the lasting appeal of her literale comic sensibility. Sex and violence are he intertwined themes. Se/f-Port,a, (1963) presents a skimpily cloo Sylvia Sleigh: Detail of Invitation to a Voyage, 1979-99, oil on canvas , 14 panels, 8 by 70 feet overall; at Deven Golden. prone woman against a rel background with her high heel. in the air and her face obscurocf Gardner is good with planes, import, over the years , of her Arsenal , a castlelike fortress by a pillow . The large-seal! O both when delineated as in self-portraits as Venus as well built on an island in the early image s in what is perhap. Untitled (Bhoadie, Nick, S, Matt as the idealized male nudes of 20th century by eccentr ic & Tim playing basketball, The Turkish Bath (1973), art crit Scottish-American millionaire Victoria) or when intimated as in ics all, including her husband, Frank Bannerman to house part Untitled (S pissing). The latter the late Lawrence Alloway. of his military-surplus business. was one of the best pieces in Perh aps the practice harks Sleigh first glimpsed the place the exhibition. The urine spot on back to Sleigh 's charmed from the window of an Amtrak the ground is delicately evoked, girlhood in Wales; perhaps train, and on a mild spring day as is the stream of urine, which it ha s something to do with a some time later she organized a has the prec ision of a Persian European tendency to allegory riverbank picnic to take advan miniature. -

The Museum of Modern Art: the Mainstream Assimilating New Art

AWAY FROM THE MAINSTREAM: THREE ALTERNATIVE SPACES IN NEW YORK AND THE EXPANSION OF ART IN THE 1970s By IM SUE LEE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Im Sue Lee 2 To mom 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful to my committee, Joyce Tsai, Melissa Hyde, Guolong Lai, and Phillip Wegner, for their constant, generous, and inspiring support. Joyce Tsai encouraged me to keep working on my dissertation project and guided me in the right direction. Mellissa Hyde and Guolong Lai gave me administrative support as well as intellectual guidance throughout the coursework and the research phase. Phillip Wegner inspired me with his deep understanding of critical theories. I also want to thank Alexander Alberro and Shepherd Steiner, who gave their precious advice when this project began. My thanks also go to Maureen Turim for her inspiring advice and intellectual stimuli. Thanks are also due to the librarians and archivists of art resources I consulted for this project: Jennifer Tobias at the Museum Library of MoMA, Michelle Harvey at the Museum Archive of MoMA, Marisa Bourgoin at Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, Elizabeth Hirsch at Artists Space, John Migliore at The Kitchen, Holly Stanton at Electronic Arts Intermix, and Amie Scally and Sean Keenan at White Columns. They helped me to access the resources and to publish the archival materials in my dissertation. I also wish to thank Lucy Lippard for her response to my questions. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL (on the cover): Alice Nee I, Mary D. Garrard (1977), FALL I WINTER 2006 VOLUME 27, NUMBER 2 oil on canvas, 331/4" x 291/4". Private collection. 2 PARALLEL PERSPECTIVES By Joan Marter and Margaret Barlow PORTRAITS, ISSUES AND INSIGHTS 3 ALICE EEL A D M E By Mary D. Garrard EDITORS JOAN MARTER AND MARGARET B ARLOW 8 ALI CE N EEL'S WOMEN FROM THE 1970s: BACKLASH TO FAST FORWA RD By Pamela AHara BOOK EDITOR : UTE TELLINT 12 ALI CE N EE L AS AN ABSTRACT PAINTER FOUNDING EDITOR: ELSA HONIG FINE By Mira Schor EDITORIAL BOARD 17 REVISITING WOMANHOUSE: WELCOME TO THE (DECO STRUCTED) 0 0LLHOUSE NORMA BROUDE NANCY MOWLL MATHEWS By Temma Balducci THERESE DoLAN MARTIN ROSENBERG 24 NA CY SPERO'S M USEUM I CURSIO S: !SIS 0 THE THR ES HOLD MARY D. GARRARD PAMELA H. SIMPSON By Deborah Frizzell SALOMON GRIMBERG ROBERTA TARBELL REVIEWS ANN SUTHERLAND HARRis JUDITH ZILCZER 33 Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism ELLEN G. LANDAU EDITED BY N ORMA BROUDE AND MARY D. GARRARD Reviewed by Ute L. Tellini PRODUCTION, AND DESIGN SERVICES 37 The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine De Pizan's O LD CITY P UBLISHING, INC. Renaissance Legacy BYS uSAN GROAG BELL Reviewed by Laura Rinaldi Dufresne Editorial Offices: Advertising and Subscriptions: Woman's Art journal Ian MeUanby 40 Intrepid Women: Victorian Artists Travel Rutgers University Old City Publishing, Inc. EDITED BY JORDANA POMEROY Reviewed by Alicia Craig Faxon Dept. of Art History, Voorhees Hall 628 North Second St. -

Curriculum Vitae Table of Contents

CURRICULUM VITAE Revised February 2015 ADRIAN MARGARET SMITH PIPER Born 20 September 1948, New York City TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Educational Record ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Languages...................................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Philosophy Dissertation Topic.................................................................................................................. 2 4. Areas of Special Competence in Philosophy ......................................................................................... 2 5. Other Areas of Research Interest in Philosophy ................................................................................... 2 6. Teaching Experience.................................................................................................................................... 2 7. Fellowships and Awards in Philosophy ................................................................................................. 4 8. Professional Philosophical Associations................................................................................................. 4 9. Service to the Profession of Philosophy .................................................................................................. 5 10. Invited Papers and Conferences in Philosophy ................................................................................. -

150 a Tremendous Success").2

150 FIG.4.1 Installation view, Don Judd, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 27 FebruarY-24 March 1968 Curator, William C. Agee THE OPENING OF OONALD JUDD'S solo exhibition at catalogue raisonn. designation Untitled rOSS 79] [fig. 4.3]), the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1968 sealed his "As an object, the box was very much there ... Its. whole reputation as a central figure in contemporary art. William purpose seemed to be the declaration of some blunt quid C. Agee, the curator, had packed Judd's sheet-metal sculp dityand nothing more."'ln the years since, Judd's works tures fairly tightly into what at least one critic described as have likewise appeared "blunt, unambiguous," "completely a warehouselike installation,and the tidy right angles and present," "just existing," and "simply 'there.' "5 Each sculp repetitive modularity of the works made a neat match to ture has asserted itself as· "simply another thing in the world the stone tiles and concrete ceUing coffers of the museum's of things."'ln the 1967 essay "Art andObjecthood," which two-year-old Marcel Breuer building (fig. 4.1).' Sitting remains the single most influential account of Minimalism, brightly in the middle of the space, Untitled (OSS 128) (fig. Michael Fried characterized Judd's work (together with that 4.2) exemplified the overall appearance of the exhibition: of Robert Morris and others) as a "literalist art" that insisted a shiny rectangle of amber Plexiglas with a thin and hollow on its own occupation of ordinary space and time? By the stainless.-steel core. -

Visual AIDS and Day Without Art, 1988–1989

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-4-2020 Mobilizing Museums Against AIDS: Visual AIDS and Day Without Art, 1988–1989 Kyle Croft CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/578 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Mobilizing Museums Against AIDS: Visual AIDS and Day Without Art, 1988–1989 by Kyle Croft Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 May 4, 2020 Howard Singerman Date Thesis Sponsor May 4, 2020 Lynda Klich Date Second Reader TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments iii List of Illustrations iv Introduction: December 1, 1989 1 Chapter 1: What can art do about AIDS? 10 A crisis of representation 13 Robert Atkins: AIDS Memorial Quilt 17 William Olander: Let The Record Show… 19 Thomas Sokolowski: Rosalind Solomon: Portraits in the Time of AIDS 26 Gary Garrels: AIDS and Democracy: A Case Study 29 Strategies of public address 36 Chapter 2: The art world organizes 39 Moratorium 43 John Perreault: Demanding Action 47 Philip Yenawine: Museums as Resources 49 Increasing the options 51 Becoming official 56 Making headlines 59 Chapter 3: Working from within 63 AIDS at the Museum of Modern Art 65 Mobilizing the Modern 67 Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing 79 A Gathering of Hope 82 Moving the needle 86 Conclusion: AIDS Ongoing, Going On 90 Archival Sources and Bibliography 95 Illustrations 104 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was first introduced to the history of Day Without Art during an internship at Visual AIDS in 2015. -

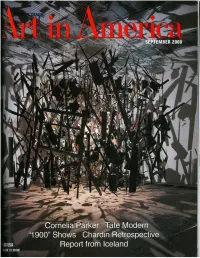

Art in America: Pattern Recognition

foundations Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Pattern Recognition In the 1970s and ’80s a bold group of American artists embraced vibrant color, ornament, and craft. By Glenn Adamson Miriam Schapiro: Again Sixteen Windows, 1973, spray paint, watercolor, and fabric on paper, 30½ by 22½ inches. © Estate of Miriam Schapiro/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Eric Firestone Gallery. © Estate of Miriam Schapiro/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 40 September 2019 41 foundations when she died of cancer in April 1978. It all adds up to an extremely convincing case for the relevance of the Pattern and Decoration movement, which Katz sees not as a divergence from more weighty avant-garde matters, but on the contrary, the key turning point in recent art. To grasp the force of this argument, it helps to expand on an observation about P&D by New York Times critic Holland Cotter: it was “the last genuine art move- ment of the twentieth century.”² In a weak sense, this is true just because of the great fragmentation that came right after—the rupture of postmodernism. The bellwether “Pictures” show at Artists Space in 1977, coin- ciding with P&D’s peak, augured a crisis of authorship, most clearly exemplified by appropriation-based practic- es. Though postmodernist art shared certain strategies with Pattern and Decoration work—fragmentary collage and an emphasis on the signifying surface—it tended to be more theoretical and introverted, often hostile to “grand narratives” of progress. -

SYLVIA SLEIGH 330 West 20Th Street New York, NY 10011 212-691-5558

Updated Wednesday, March 07, 2007 SYLVIA SLEIGH 330 West 20th Street New York, NY 10011 212-691-5558 www.sylviasleigh.com Born in Llandudno, Wales Lives and works in New York SELECTED ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2006 Sylvia Sleigh: Invitation to a Voyage; The Hudson River Museum 511 Warburton Avenue, Yonkers, NY 10701 www.hrm.org 2005 Sylvia Sleigh: Portraits and Group Portraits; Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art, Snug Harbor Cultural Center, Staten Island, NY 2004 Sylvia Sleigh: New Work & Portraits of Critics; SOHO 20 Chelsea, New York, NY 2001 An Unnerving Romanticism: The Art of Sylvia Sleigh and Lawrence Alloway The Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, PA 1999 Invitation to a Voyage and Other Works Deven Golden Fine Arts, New York, NY Parallel Visions: Portraits of Women Artists and Writers Soho20, New York, NY 1995 Invitation to a Voyage and Other Works Zaks Gallery, Chicago, IL 1994 Sylvia Sleigh: New Paintings Stiebel Modern, New York, NY 1992 Paintings from the 1970's Stiebel Modern, New York, NY 1990 Sylvia Sleigh: Invitation to a Voyage and Other Works Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI; traveled to Ball State University Art Gallery, Muncie, IN; Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH 1985 Invitation to a Voyage: The Hudson River at Fishkill G.W. Einstein Co., Inc., New York, NY Nudes and Portraits Zaks Gallery, Chicago, IL Drawings SoHo 20 Gallery, New York, NY 1983 Sylvia Sleigh Paints Lawrence Alloway G.W. Einstein Co., Inc., New York, NY 1982 Portraits at the New School Associates Gallery, New School of Social Research, New York, NY 1981 Gallery 210 University of Missouri, St. -

Alice Neel's American Portrait Gallery

Pictures of People Pictures of People Alice Neel’s American Portrait Gallery Pamela Allara Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755 © 1998 by the Trustees of Brandeis University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN for paperback edition: 978–1–61168–513–8 ISBN for ebook edition: 978–1–61168–049–2 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Allara, Pamela. Pictures of people : Alice Neel’s American portrait gallery / by Pamela Allara. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–87451–837–7 1. Neel, Alice, 1900– —Criticism and interpretation. 2. United States— Biography—Portraits. I. Neel, Alice, 1900– . II. Title. ND1329.N36A9 1998 97–18403 759.13—DC21 Throughout this book, “Estate of Alice Neel” includes works in the collections of Richard Neel, Hartley S. Neel, their respective families, and Neel Arts, Inc. 5432 NOTE TO EREADERS As electronic reproduction rights are unavailable for images appearing in this book’s print edition, no illustrations are included in this ebook. Readers interested in seeing the art referenced here should either consult this book’s print edition or visit an online resource such as aliceneel.com or artstor.org. vi CONTENTS illustrations included in the print edition ix acknowledgments xv Introduction: The Portrait Gallery xvii PART I: THE SUBJECTS OF THE ARTIST Chapter 1: The Creation (of a) Myth 3 Chapter 2: From Portraiture -

Pattern and Decoration an Ideal Vision in American Art, 1975–1985

Pattern and Decoration An Ideal Vision in American Art, 1975–1985 EditEd by AnnE SwArtz HUdSOn RIVEr MUSEUM Lenders to the Exhibition dr. Melvin and Mrs. nora berlin Janet and david brinton brad davis danielle dutry Flomenhaft Gallery Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, new york Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian institution, washington, d.C. the Estate of Horace H. Solomon Valerie Jaudon Jane Kaufman Joyce Kozloff Kim MacConnel the Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, Florida Polk Museum of Art, Lakeland, Florida Private Collections Françoise and Harvey rambach tony robbin ned Smyth ABOVE RIGHT: ValeriE JaudOn robert zakanitch Toomsuba, 1973 Mr. and Mrs. Howard zipser Contents 4 director’s Foreword 49 deluxe redux: Legacies of the Michael Botwinick Pattern and decoration Movement John PErreault 6 Curator’s Acknowledgments AnnE SwArtz 57 Artists and Plates AnnE SwArtz 7 Pattern and decoration as a Late Modernist Movement 113 A Chronology of Pattern and decoration Arthur C. DantO AnnE SwArtz 12 Pattern and decoration: 120 Exhibition Checklist An ideal Vision in American Art AnnE SwArtz 43 the Elephant in the room: Pattern and decoration, Feminism, Aesthetics, and Politics Temma Balducci Director’s Foreword miss is the powerful commitment of the artists MiCHAEL bOTWINICK to the surface and their virtuosity in dealing with it. Critics also miss the urgent way these while there is general consensus that artists sought to push the margins of what was enough time has passed to allow for a “first acceptable vocabulary for art. And finally, they draft” assessment of the 1970s, Pattern and miss the ways Pattern and decoration turns our decoration remains stubbornly resistant to expectations upside down by appropriating rediscovery. -

Alice Neel Born 1900 in Merion Square, Pennsylvania

This document was updated September 28, 2019. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Alice Neel Born 1900 in Merion Square, Pennsylvania. Died 1984 in New York. EDUCATION 1921-1925 Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art and Design) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Alice Neel: Freedom, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] Neel / Picasso, Sara Kay Gallery, New York [two-person exhibition] 2018 Alice Neel in New Jersey and Vermont, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels 2017 Alice Neel: The Great Society, Aurel Scheibler, Berlin [catalogue published in 2018] Alice Neel, Uptown, David Zwirner, New York [itinerary: Victoria Miro, London] [catalogue] 2016 Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life, Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki [itinerary: Gemeentemuseum, The Hague; Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, Arles, France; Deichtorhallen Hamburg] [catalogue] Alice Neel: The Subject and Me, Talbot Rice Gallery, The University of Edinburgh [catalogue] 2015 Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors 1927-1978, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] Alice Neel, Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Zurich [exhibition publication] Alice Neel, Xavier Hufkens, Brussels [catalogue] 2014 Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field: Painting the People, Bennington Museum, Vermont [two- person exhibition] Alice Neel: My Animals and Other Family, Victoria Miro, London [catalogue] 2013 Alice Neel: Intimate Relations - Drawings and Watercolours 1926-1982, Nordiska Akvarellmuseet, Skärhamn, Sweden [catalogue] People and Places: Paintings by