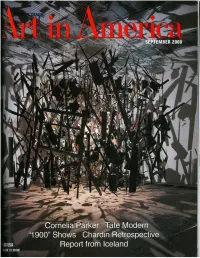

Art in America: Pattern Recognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, Ve Aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Jonathan Vimr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Vimr, Jonathan, "Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 211. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 Suggested Citation: Vimr, Jonathan (2013). Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Abstract Just as architectural history traditionally takes the form of a march of styles, so too do preservationists repeatedly campaign to save seminal works of an architectural manner several decades after its period of prominence. This is currently happening with New Brutalism and given its age and current unpopularity will likely soon befall postmodern historicism. In hopes of preventing the loss of any of the manner’s preeminent works, this study provides professionals with a framework for evaluating the significance of postmodern historicist designs in relation to one another. Through this, the limited resources required for large-scale preservation campaigns can be correctly dedicated to the most emblematic sites. Three case studies demonstrate the application of these criteria and an extended look at recent preservation campaigns provides lessons in how to best proactively preserve unpopular sites. -

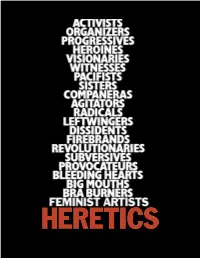

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Percent for Art in New York City

Percent for Art in New York City 1965 Mayor Robert Wagner issues an executive order supporting the inclusion of artwork in City buildings. Few agencies take advantage of this opportunity. 1971-1975 Doris Freedman (1928-1981), founder of the Public Art Fund and Director of the Office of Cultural Affairs within the Department of Parks and Recreation and Culture, drafts Percent for Art legislation and begins to lobby the City Council. The City becomes immersed in a fiscal crisis and the legislation lies dormant. 1976 The Office of Cultural Affairs becomes a separate agency: The Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA). 1978 Edward I. Koch is elected Mayor of New York City. 1981 As the City emerges from fiscal crisis, the administration and City Council begin to contemplate Percent for Art legislation. Deputy Mayor Ronay Menschel and Chief of Staff Diane Coffey are key advocates. 1982 City Council passes Percent for Art legislation; Mayor Koch signs it into law. Percent for Art Law requires that one percent of the budget for eligible City-funded construction is dedicated to creating public artworks. 1983 The Percent for Art law is enacted. Overseen by DCA Commissioner Henry Geldzahler and Deputy Commissioner Randall Bourscheidt, the program is initially administered by the Public Art Fund (Director, Jenny Dixon). Jennifer McGregor is the program’s Administrator. Following the example of the City’s Percent for Art legislation, the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) establishes a similar program for its capital construction projects. During the early years of its existence, the MTA’s art selection panels are chaired and coordinated by DCA’s commissioner. -

Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected]

1 Patricia Hills Professor Emerita, American and African American Art Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University [email protected] Education Feb. 1973 PhD., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Thesis: "The Genre Painting of Eastman Johnson: The Sources and Development of His Style and Themes," (Published by Garland, 1977). Adviser: Professor Robert Goldwater. Jan. 1968 M.A., Hunter College, City University of New York. Thesis: "The Portraits of Thomas Eakins: The Elements of Interpretation." Adviser: Professor Leo Steinberg. June 1957 B.A., Stanford University. Major: Modern European Literature Professional Positions 9/1978 – 7/2014 Department of History of Art & Architecture, Boston University: Acting Chair, Spring 2009; Spring 2012. Chair, 1995-97; Professor 1988-2014; Associate Professor, 1978-88 [retired 2014] Other assignments: Adviser to Graduate Students, Boston University Art Gallery, 2010-2011; Director of Graduate Studies, 1993-94; Director, BU Art Gallery, 1980-89; Director, Museum Studies Program, 1980-91 Affiliated Faculty Member: American and New England Studies Program; African American Studies Program April-July 2013 Terra Foundation Visiting Professor, J. F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität, Berlin 9/74 - 7/87 Adjunct Curator, 18th- & 19th-C Art, Whitney Museum of Am. Art, NY 6/81 C. V. Whitney Lectureship, Summer Institute of Western American Studies, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming 9/74 - 8/78 Asso. Prof., Fine Arts/Performing Arts, York College, City University of New York, Queens, and PhD Program in Art History, Graduate Center. 1-6/75 Adjunct Asso. Prof. Grad. School of Arts & Science, Columbia Univ. 1/72-9/74 Asso. -

Aesthetics Between History, Geography and Media

volume 11 _2019 No _2 s e r b i a n a r c hS i t e c t u rA a l j o u rJ n a l ICA 2019 21ST ICA POSSIBLE WORLDS OF CONTEMPORARY AESTHETICS: AESTHETICS BETWEEN HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY AND MEDIA PART 1 _2019_2_ Serbian Architectural Journal is published in Serbia by the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, with The Centre for Ethics, Law and Applied Philosophy, and distributed by the same institutions / www.saj.rs All rights reserved. No part of this jornal may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means [including photocopying, recording or information storage and retrieval] without permission in writing from the publisher. This and other publisher’s books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For informations, please email at [email protected] or write to following adress. Send editorial correspondence to: Serbian Architectural Journal Faculty of Architecture Bulevar Kralja Aleksandra 73/II 11 120 Belgrade, Serbia ISSN 1821-3952 cover image: Official Conference Graphics, Boško Drobnjak, 2019. s e r b i a n a r c hS i t e c t u rA a l j o u rJ n a l 21ST ICA POSSIBLE WORLDS OF CONTEMPORARY AESTHETICS: AESTHETICS BETWEEN HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY AND MEDIA volume 11 _2019 No _2 PART 1 _2019_2_ s e r b i a n a r c h i t e c t u r a l j o u r n a l EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Vladan Djokić EDITORIAL BOARD: Petar Bojanić, University of Belgrade, Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, Serbia; University of Rijeka, CAS – SEE, Croatia Vladan Djokić, University of Belgrade, -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Rosalyn Drexler at Mitchell Algus Ans Nicholas Davies

bringing hard-edged , often ro lent imagery from film noir alll tabloid culture into the Poi arena. Known also as a plat wright and novelist , Drexler r her youth enjoyed a brief stintas , a professional wrestler. Ths dual -ven ue selection of bol '60s work and recent painting! and collages more than proves the lasting appeal of her literale comic sensibility. Sex and violence are he intertwined themes. Se/f-Port,a, (1963) presents a skimpily cloo Sylvia Sleigh: Detail of Invitation to a Voyage, 1979-99, oil on canvas , 14 panels, 8 by 70 feet overall; at Deven Golden. prone woman against a rel background with her high heel. in the air and her face obscurocf Gardner is good with planes, import, over the years , of her Arsenal , a castlelike fortress by a pillow . The large-seal! O both when delineated as in self-portraits as Venus as well built on an island in the early image s in what is perhap. Untitled (Bhoadie, Nick, S, Matt as the idealized male nudes of 20th century by eccentr ic & Tim playing basketball, The Turkish Bath (1973), art crit Scottish-American millionaire Victoria) or when intimated as in ics all, including her husband, Frank Bannerman to house part Untitled (S pissing). The latter the late Lawrence Alloway. of his military-surplus business. was one of the best pieces in Perh aps the practice harks Sleigh first glimpsed the place the exhibition. The urine spot on back to Sleigh 's charmed from the window of an Amtrak the ground is delicately evoked, girlhood in Wales; perhaps train, and on a mild spring day as is the stream of urine, which it ha s something to do with a some time later she organized a has the prec ision of a Persian European tendency to allegory riverbank picnic to take advan miniature. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Monday, August 19, 2019 MOCA

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Monday, August 19, 2019 MOCA PRESENTS WITH PLEASURE: PATTERN AND DECORATION IN AMERICAN ART 1972–1985 October 27, 2019–May 11, 2020 MOCA Grand Avenue LOS ANGELES—This fall The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) presents With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, the first full-scale scholarly North American survey of the groundbreaking yet understudied Pattern and Decoration art movement. Including painting, sculpture, collage, ceramics, textiles, installation art, and performance documentation, the exhibition spans the years 1972 to 1985 and features forty-five artists from across the United States. With Pleasure examines the Pattern and Decoration movement’s defiant embrace of forms traditionally coded as feminine, domestic, ornamental, or craft-based and thought to be categorically inferior to fine art. This expansive exhibition traces the movement’s broad reach in postwar American art by including artists widely regarded as comprising the core of the movement, such as Valerie Jaudon, Joyce Kozloff, Robert Kushner, Kim MacConnel, and Miriam Schapiro; artists whose contributions to Pattern and Decoration have been underrecognized, such as Merion Estes, Dee Shapiro, Kendall Shaw, and Takako Yamaguchi; as well as artists who are not normally considered in the MOCA PRESENTS WITH PLEASURE: PATTERN AND DECORATION IN AMERICAN ART 1972–1985 Page 2 of 5 context of Pattern and Decoration, such as Emma Amos, Billy Al Bengston, Al Loving, and Betty Woodman. Organized by MOCA Curator Anna Katz, with Assistant Curator Rebecca Lowery, the exhibition will be on view at MOCA Grand Avenue from October 27, 2019 to May 11, 2020. It is accompanied by a fully illustrated, scholarly catalogue published in association with Yale University Press. -

The Museum of Modern Art: the Mainstream Assimilating New Art

AWAY FROM THE MAINSTREAM: THREE ALTERNATIVE SPACES IN NEW YORK AND THE EXPANSION OF ART IN THE 1970s By IM SUE LEE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Im Sue Lee 2 To mom 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful to my committee, Joyce Tsai, Melissa Hyde, Guolong Lai, and Phillip Wegner, for their constant, generous, and inspiring support. Joyce Tsai encouraged me to keep working on my dissertation project and guided me in the right direction. Mellissa Hyde and Guolong Lai gave me administrative support as well as intellectual guidance throughout the coursework and the research phase. Phillip Wegner inspired me with his deep understanding of critical theories. I also want to thank Alexander Alberro and Shepherd Steiner, who gave their precious advice when this project began. My thanks also go to Maureen Turim for her inspiring advice and intellectual stimuli. Thanks are also due to the librarians and archivists of art resources I consulted for this project: Jennifer Tobias at the Museum Library of MoMA, Michelle Harvey at the Museum Archive of MoMA, Marisa Bourgoin at Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, Elizabeth Hirsch at Artists Space, John Migliore at The Kitchen, Holly Stanton at Electronic Arts Intermix, and Amie Scally and Sean Keenan at White Columns. They helped me to access the resources and to publish the archival materials in my dissertation. I also wish to thank Lucy Lippard for her response to my questions. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL (on the cover): Alice Nee I, Mary D. Garrard (1977), FALL I WINTER 2006 VOLUME 27, NUMBER 2 oil on canvas, 331/4" x 291/4". Private collection. 2 PARALLEL PERSPECTIVES By Joan Marter and Margaret Barlow PORTRAITS, ISSUES AND INSIGHTS 3 ALICE EEL A D M E By Mary D. Garrard EDITORS JOAN MARTER AND MARGARET B ARLOW 8 ALI CE N EEL'S WOMEN FROM THE 1970s: BACKLASH TO FAST FORWA RD By Pamela AHara BOOK EDITOR : UTE TELLINT 12 ALI CE N EE L AS AN ABSTRACT PAINTER FOUNDING EDITOR: ELSA HONIG FINE By Mira Schor EDITORIAL BOARD 17 REVISITING WOMANHOUSE: WELCOME TO THE (DECO STRUCTED) 0 0LLHOUSE NORMA BROUDE NANCY MOWLL MATHEWS By Temma Balducci THERESE DoLAN MARTIN ROSENBERG 24 NA CY SPERO'S M USEUM I CURSIO S: !SIS 0 THE THR ES HOLD MARY D. GARRARD PAMELA H. SIMPSON By Deborah Frizzell SALOMON GRIMBERG ROBERTA TARBELL REVIEWS ANN SUTHERLAND HARRis JUDITH ZILCZER 33 Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism ELLEN G. LANDAU EDITED BY N ORMA BROUDE AND MARY D. GARRARD Reviewed by Ute L. Tellini PRODUCTION, AND DESIGN SERVICES 37 The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine De Pizan's O LD CITY P UBLISHING, INC. Renaissance Legacy BYS uSAN GROAG BELL Reviewed by Laura Rinaldi Dufresne Editorial Offices: Advertising and Subscriptions: Woman's Art journal Ian MeUanby 40 Intrepid Women: Victorian Artists Travel Rutgers University Old City Publishing, Inc. EDITED BY JORDANA POMEROY Reviewed by Alicia Craig Faxon Dept. of Art History, Voorhees Hall 628 North Second St.