Pulp Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Incredible, Once-In-A-Lifetime Munsey/Popular Publications Auction – Part 2!

The Incredible, Once-in-a-Lifetime Munsey/Popular Publications Auction – Part 2! As part of the Windy City Pulp and Paperback Convention’s Saturday night auction (beginning at approximately 8:00 p.m., following the Guest of Honor presentation), we will be presenting more material from the Munsey and Popular Publications archives. These lots will be mixed-in with the other lots during the auction. Please note that the listing below is subject to change and does not necessarily represent the order in which items will be auctioned. While we have endeavored to describe these lots carefully, bidders should personally examine the lots they’re interested in and raise any questions prior to the auction; the convention is not responsible for errors in descriptions. Purchase of any of these items at auction does not transfer copyright permissions or grant reprint permissions. When carbon letters are mentioned in connection with lots containing author correspondence, these are usually carbon copies of letters coming from various editors at Munsey or Popular Publications, replying to the author. * * * * * 1. REX STOUT - Munsey check endorsed by Stout for his novel, The Great Legend, from 1914. 2. JAMES FRANCIS DWYER - Munsey check (and copyright notice also) both endorsed by Dwyer for his novel, The White Waterfall, from 1912. 3. MODEST STEIN - Munsey check endorsed by Stein for his cover painting for The Radio Planet from 1926. 4. RAY CUMMINGS - Munsey check endorsed by Cummings for his novel, Tama of the Flying Virgins from 1930. 5. CHARLES WILLIAMS - Munsey check endorsed by Williams for his cover painting for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Girl from Farris’s from 1916. -

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

David Goodis: Five Noir Novels of the 1940S and 50S Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DAVID GOODIS: FIVE NOIR NOVELS OF THE 1940S AND 50S PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Goodis, Robert Polito | 848 pages | 16 Oct 2014 | The Library of America | 9781598531480 | English | New York, United States David Goodis: Five Noir Novels of the 1940s and 50s PDF Book To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. My impression, and I'm nowhere near the end of reading all of Goodis, is that he is a kind of American Sartre, a two-fisted Dante being backed into a solid wall of desperation and doubt. It will allow future generations to plunge into the luxurious sensation one experiences when reading a Goodis novel, even though it never lasts for long, and is accompanied by the dismal knowledge that it will soon be over. Robert Polito Editor. Parry steps into the room, and addresses his best friend:. May 27, Ben rated it liked it. Goodis is more like a Mickey Spillane with a soul. Robin Friedman I don't feel that this is a fault, however, because I believe Goodis's surrealism is intentional. One of the problems with this is clunky plotting. How to read this? Project support for this volume was provided by the Geoffrey C. He is overly reliant on coincidence and often having a character overhear long sections of dialogue. I much-loved the anthology, especially "Street of No Return. Nicholson Baker. No trackbacks yet. And then the reach for the lever that opens the strongbox and While hitchhiking he is picked up by a woman named Irene Janney. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

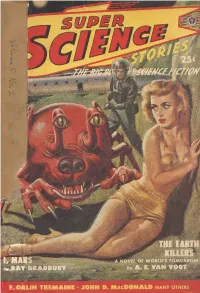

Super Science Stories V05n02 (1949 04) (Slpn)

’yf'Ti'-frj r " J * 7^ i'irT- 'ii M <»44 '' r<*r^£S JQHN D. Macdonald many others ) _ . WE WILL SEND ANY ITEM YOU CHOOSE rOR APPROVAL UNDER OUR MONEY BACK GUARANTEE Ne'^ MO*' Simply Indicate your selection on the coupon be- low and forward it with $ 1 and a brief note giv- ing your age, occupotion, and a few other facts about yourself. We will open an account for ycu and send your selection to you subject to your examination, tf completely satisfied, pay the Ex- pressman the required Down Payment and the balance In easy monthly payments. Otherwise, re- turn your selection and your $1 will be refunded. A30VC112 07,50 A408/C331 $125 3 Diamond Engagement 7 Dtomond Engagement^ Ring, matching ‘5 Diamond Ring, matching 8, Dior/tond Wedding Band. 14K yellow Wedding 5wd. 14K y<dlow or IBK white Gold. Send or I8K white Cold, fiend $1, poy 7.75 after ex- $1, pay .11.50 after ex- amination, 8.75 a month. aminatioii, 12.50 a month. ^ D404 $75 Man's Twin Ring with 2 Diamonds, pear-shaped sim- ulated Ruby. 14K yellow Gold. Send $1, pay 6.50 after examination, 7.50 a month* $i with coupon — pay balance op ""Tend [ DOWN PAYMENT AFTER EXAMINATION. I, ''All Prices thciude ''S T'" ^ ^ f<^erat fox ", 1. W. Sweet, 25 West 1 4th St. ( Dept. PI 7 New York 1 1, N, Y. Enclosed find $1 deposit. Solid me No. , , i., Price $ - After examination, I ogree to pay $ - - and required balance monthly thereafter until full price . -

The Autobiographical Fiction of Charles Bukowski Daniel Bigna A

Life on the Margins: The Autobiographical Fiction of Charles Bukowski Daniel Bigna A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors Susan Lever, Heather Neilson and Jeff Doyle for invaluable guidance and support, and Fiona, Simon and Jamie for infinite patience and encouragement. I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no material previously published or written by another person, nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicity acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. 1 Chapter One - Bukowski in Context. 24 Chapter Two – The Development of Bukowski’s Alternative Literary 48 Aesthetic in the novels Post Office , Factotum and Women. Chapter Three - Ham on Rye - The Troubled Birth of an Artist. 89 Chapter Four - Hot Water Music - The Grotesque and 108 the Artist Demystified. Chapter Five - Hollywood - A Non-Conformist in a Strange World. -

Graphic No Vels & Comics

GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS SPRING 2020 TITLE Description FRONT COVER X-Men, Vol. 1 The X-Men find themselves in a whole new world of possibility…and things have never been better! Mastermind Jonathan Hickman and superstar artist Leinil Francis Yu reveal the saga of Cyclops and his hand-picked squad of mutant powerhouses. Collects #1-6. 9781302919818 | $17.99 PB Marvel Fallen Angels, Vol. 1 Psylocke finds herself in the new world of Mutantkind, unsure of her place in it. But when a face from her past returns only to be killed, she seeks vengeance. Collects Fallen Angels (2019) #1-6. 9781302919900 | $17.99 PB Marvel Wolverine: The Daughter of Wolverine Wolverine stars in a story that stretches across the decades beginning in the 1940s. Who is the young woman he’s fated to meet over and over again? Collects material from Marvel Comics Presents (2019) #1-9. 9781302918361 | $15.99 PB Marvel 4 Graphic Novels & Comics X-Force, Vol. 1 X-Force is the CIA of the mutant world—half intelligence branch, half special ops. In a perfect world, there would be no need for an X-Force. We’re not there…yet. Collects #1-6. 9781302919887 | $17.99 PB Marvel New Mutants, Vol. 1 The classic New Mutants (Sunspot, Wolfsbane, Mirage, Karma, Magik, and Cypher) join a few new friends (Chamber, Mondo) to seek out their missing member and go on a mission alongside the Starjammers! Collects #1-6. 9781302919924 | $17.99 PB Marvel Excalibur, Vol. 1 It’s a new era for mutantkind as a new Captain Britain holds the amulet, fighting for her Kingdom of Avalon with her Excalibur at her side—Rogue, Gambit, Rictor, Jubilee…and Apocalypse. -

Downloaded from by Guest on 26 June 2020

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Crime Fiction and Black Criminality Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8zw7q50m Author Martin, Theodore Publication Date 2018-10-17 DOI 10.1093/alh/ajy037 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Crime Fiction and Black Criminality Theodore Martin* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/alh/article-abstract/30/4/703/5134081 by guest on 26 June 2020 Nor was I up to being both criminal and detective—though why criminal Ididn’tknow. Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man 1. The Criminal Type A remarkable number of US literature’s most recognizable criminals reside in mid-twentieth-century fiction. Between 1934 and 1958, James M. Cain gave us Frank Chambers and Walter Huff; Patricia Highsmith gave us Charles Bruno and Tom Ripley; Richard Wright gave us Bigger Thomas and Cross Damon; Jim Thompson gave us Lou Ford and Doc McCoy; Dorothy B. Hughes gave us Dix Steele. Many other once-estimable authors of the middle decades of the century—like Horace McCoy, Vera Caspary, Charles Willeford, and Willard Motley—wrote novels centrally concerned with what it felt like to be a criminal. What, it is only natural to wonder, was this midcentury preoccupation with crime all about? Consider what midcentury crime fiction was not about: detec- tives. Although scholars of twentieth-century US literature often use the phrases crime fiction and detective fiction interchangeably, the detective and the criminal were, by midcentury, the anchoring pro- tagonists of two distinct genres. While hardboiled detectives contin- ued to dominate the literary marketplace of pulp magazines and paperback originals in the 1940s and 1950s, they were soon accom- panied on the shelves by a different kind of crime fiction, which was *Theodore Martin is Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Contemporary Drift: Genre, Historicism, and the Problem of the Present (Columbia UP, 2017). -

From the Director “What Is Feminist Politics Now

IRWaG FEMINIST NEWS ~ PAGE 1 Volume 26 ■ August 2008 ■ Columbia University ■ New York THE NEWSLETTER OF THE From the Director INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH ON WOMEN AND GENDER As reported in a previous column, Marianne Institute for Comparative Society and Literature, the In This Issue: Hirsch and I will be playing “IRWaG Director tag” Institute for Research in African-American Studies, Feminist Legacies of Columbia ’68 for four years. I would like to begin my term by and the Barnard Center for Research on Women. 2 thanking Marianne for her stellar leadership and I would also like to thank the various Feminist Interventions: exemplary governorship. Not only did she efficiently members of IRWaG who have agreed to share Gender and Public Health: and deftly administer the Institute and fill the their intellectual and administrative energies for Cutting Edge Research academic year with a variety of critically engaging the current academic year, including the members 3 talks, workshops, and conferences, she helped of the Columbia and Barnard community who News Briefs initiate, with Sharon Marcus (Professor, English), a teach classes and sponsor events at the heart of 3 new graduate student fellowship program. Along our mission; Julie Crawford who is continuing as with administrative duties, our first four fellows, Jess Director of Undergraduate Studies; Alice Kessler- Fenn, Melissa Gonzales, Jenny James, and Sara Harris who will serve as the Director of Graduate Kile, provided intellectual leadership and energy Studies; and the members of the Steering that bridged faculty and graduate student interests Committee: Lila Abu-Lughod, Madeleine Dobie, to produce a number of exciting and well-attended Eileen Gilooly, Ellie Hisama, Laura Kay, Lydia Liu, events (See “IRWaG Graudate Colloquium”). -

Sisters in Libraries Historical Research Crime Fiction in College

h h The Sisters in Crime Quarterly Vol. 27, No. 1 Sisters in Libraries Historical Research Crime Fiction in College Awards & Rewards Getting Facts Straight Rage Fantasies… Get a Clue inSinC Editor’s Note Molly Weston ..............3 Laura’s Letter The mission of Sisters in Crime is to promote the Laura DiSilverio.............4 professional development and advancement of women crime writers to achieve equality in the industry. Sisters in Libraries Laurie King & Zoë Eckaim . 5 Laura DiSilverio, President Catriona McPherson, Vice President Chapters......................9 Stephanie Pintoff, Secretary Julie Hennrikus, Publicity Finding & Using Research in Lori Roy, Treasurer Historical Mysteries Martha Reed, Chapter Liaison Eleanor Sullivan...........12 Sally Brewster, Bookstore Liaison Carolyn Dubiel, Library Liaison Crime in the College Classroom Barbara Fister, Monitoring Project/Authors Coalition William Edwards, PhD.....14 Sally Brewster, Bookstore Liaison Carolyn Dubiel, Library Liaison Awards and Rewards Frankie Bailey, At Large Margaret Maron........... 16 Robert Dugoni, At-Large Val McDermid, At-Large Nominations & Awards Hank Phillippi Ryan, Immediate Past President Gay Toltl Kinman..........17 Molly Weston, inSinC Editor Laurel Anderson, inSinC Proofreader Writing Contests .............17 Kaye Barley, inSinC Proofreader Gavin Faulkner, inSinC Proofreader Getting Facts Straight Sarah Glass, Web Maven/Social Media Leslie Budewitz ........... 18 Rage Fantasies and Beth Wasson, Executive Secretary Character Development PO Box 442124 Lawrence, KS 66044-2124 Katherine Ramsland, PhD . 19 Email: [email protected] Events & Happenings .........21 Phone: 785.842.1325 Fax: 785.856.6314 The Docket ..................22 ©2014 Sisters in Crime International Beth’s Bits Beth Wasson .............24 inSinc is the official publication of Sisters in Crime International and is published four times a year. -

On the Square in Oxford Since 1979. U.S

Dear READER, Service and Gratitude It is not possible to express sufficiently how thankful we at Square Books have been, and remain, for the amazing support so many of you have shown to this bookstore—for forty years, but especially now. Nor can I adequately thank the loyal, smart, devoted booksellers here who have helped us take safe steps through this unprecedented difficulty, and continue to do so, until we find our way to the other side. All have shown strength, resourcefulness, resilience, and skill that maybe even they themselves did not know they possessed. We are hearing stories from many of our far-flung independent bookstore cohorts as well as other local businesses, where, in this community, there has long been—before Amazon, before Sears—a shared knowledge regarding the importance of supporting local places and local people. My mother made it very clear to me in my early teens why we shopped at Mr. Levy’s Jitney Jungle—where Paul James, Patty Lampkin, Richard Miller, Wall Doxey, and Alice Blinder all worked. Square Books is where Slade Lewis, Sid Albritton, Andrew Pearcy, Jesse Bassett, Jill Moore, Dani Buckingham, Paul Fyke, Jude Burke-Lewis, Lyn Roberts, Turner Byrd, Lisa Howorth, Sami Thomason, Bill Cusumano, Cody Morrison, Andrew Frieman, Katelyn O’Brien, Beckett Howorth, Cam Hudson, Morgan McComb, Molly Neff, Ted O’Brien, Gunnar Ohberg, Kathy Neff, Al Morse, Rachel Tibbs, Camille White, Sasha Tropp, Zeke Yarbrough, and I all work. And Square Books is where I hope we all continue to work when we’ve found our path home-free.