The Religious Foundations of Civic Virtue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republican Citizenship Richard Dagger University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science 2002 Republican Citizenship Richard Dagger University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Dagger, Richard. "Republican Citizenship." In Handbook of Citizenship Studies, edited by Engin F. Isin and Bryan S. Turner, 145-57. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2002. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 9 Republican Citizenship RICHARD DAGGER To speak of republican citizenship is to risk There might also be no need for this confusion, at least in the United States, chapter if it were not for the revival of where it is often necessary to explain that scholarly interest in republicanism in recent one is referring to 'small-r' republicanism years. Such a revival has definitely rather than a position taken by the Republi occurred, though, and occurred simultane can Party. But just as one may be a democrat ously with a renewed interest in citizenship. without being a Democrat, so one may be a This coincidence suggests that republican republican without being a Republican. The citizenship is well worth our attention, not ideas of democracy and the republic are far only for purposes of historical understand older than any political party and far richer ing but also as a way of thinking about than any partisan label can convey - rich citizenship in the twenty-first century. -

Republicanism

ONIVI C C Re PUBLICANISM ANCIENT LESSONS FOR GLOBAL POLITICS EDIT ED BY GEOFFREY C. KELLOW AND NeVEN LeDDY ON CIVIC REPUBLICANISM Ancient Lessons for Global Politics EDITED BY GEOFFREY C. KELLOW AND NEVEN LEDDY On Civic Republicanism Ancient Lessons for Global Politics UNIVERSITY OF ToronTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2016 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4426-3749-8 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable- based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication On civic republicanism : ancient lessons for global politics / edited by Geoffrey C. Kellow and Neven Leddy. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-4426-3749-8 (bound) 1. Republicanism – History. I. Leddy, Neven, editor II.Kellow, Geoffrey C., 1970–, editor JC421.O5 2016 321.8'6 C2015-906926-2 CC-BY-NC-ND This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative License. For permission to publish commercial versions please contact University of Toronto Press. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario. an Ontario government agency un organisme du gouvernement de l’Ontario Funded by the Financé par le Government gouvernement of Canada du Canada Contents Preface: A Return to Classical Regimes Theory vii david edward tabachnick and toivo koivukoski Introduction 3 geoffrey c. kellow Part One: The Classical Heritage 1 The Problematic Character of Periclean Athens 15 timothy w. -

Virtues and Vices to Luke E

CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY THE LUKE E. HART SERIES How Catholics Live Section 4: Virtues and Vices To Luke E. Hart, exemplary evangelizer and Supreme Knight from 1953-64, the Knights of Columbus dedicates this Series with affection and gratitude. The Knights of Columbus presents The Luke E. Hart Series Basic Elements of the Catholic Faith VIRTUES AND VICES PART THREE• SECTION FOUR OF CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY What does a Catholic believe? How does a Catholic worship? How does a Catholic live? Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church by Peter Kreeft General Editor Father John A. Farren, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Nihil obstat: Reverend Alfred McBride, O.Praem. Imprimatur: Bernard Cardinal Law December 19, 2000 The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed. Copyright © 2001-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council All rights reserved. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America copyright ©1994, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

Augustine's Contribution to the Republican Tradition

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Peer Reviewed Articles Political Science and International Relations 2010 Augustine’s Contribution to the Republican Tradition Paul J. Cornish Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/pls_articles Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Cornish, Paul J., "Augustine’s Contribution to the Republican Tradition" (2010). Peer Reviewed Articles. 10. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/pls_articles/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science and International Relations at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peer Reviewed Articles by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. article Augustine’s Contribution to the EJPT Republican Tradition European Journal of Political Theory 9(2) 133–148 © The Author(s), 2010 Reprints and permission: http://www. Paul J. Cornish Grand Valley State University sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav [DOI: 10.1177/1474885109338002] http://ejpt.sagepub.com abstract: The present argument focuses on part of Augustine’s defense of Christianity in The City of God. There Augustine argues that the Christian religion did not cause the sack of Rome by the Goths in 410 ce. Augustine revised the definitions of a ‘people’ and ‘republic’ found in Cicero’s De Republica in light of the impossibility of true justice in a world corrupted by sin. If one returns these definitions ot their original context, and accounts for Cicero’s own political teachings, one finds that Augustine follows Cicero’s republicanism on several key points. -

Civic Virtue Must Begin with Nitarians Especially) Worry That Widespread the Meaning of Virtue in General

C i v i c V i r t u e always under that description. One might argue, for example, that a failure in the F r a n k L o v e t t necessary congruence ultimately doomed soviet-style communism, and some (commu- Any discussion of civic virtue must begin with nitarians especially) worry that widespread the meaning of virtue in general. A virtue, on liberal individualism is gradually eroding the the standard view at least since Aristotle, is a institutional foundations of liberal societies as settled disposition exhibiting type-specific well. Though he did not use the expression excellence. Thus, for example, since the central “civic virtue,” the problem of congruence was purpose of a knife is to cut things, it is a virtue absolutely central to the third part of Rawls’s A in knives to be sharp. Similarly, one might Theory of Justice . In the mainstream tradition argue, since sociability is an important of western political thought, however, the characteristic of human beings, it is a human importance of civic virtue most strongly reso- virtue to be disposed to form friendships. To be nated among writers associated with what is a genuine virtue, of course, this disposition usually called the “classical republican” political must be firmly settled or resilient: much as it tradition. would detract from the virtuosity of an excep- The classical republicans were a diverse tionally sharp knife if its edge dulled after a group of political writers, including among single use, so too would it detract from the others Machiavelli and his fifteenth-century virtue of a human being if he or she were only a Italian predecessors; the English republicans fair-weather friend. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

Hclassification

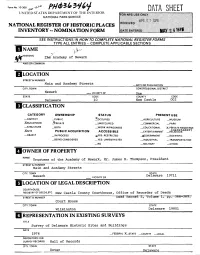

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

A Political Biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1979 A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776 John Thomas anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation anderson, John Thomas, "A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776" (1979). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625075. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tdv7-hy77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN WITHERSPOON * L FROM 1723 TO 1776 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts *y John Thomas Anderson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, September 1979 John Michael McGiffert (J ^ j i/u?wi yybirvjf \}vr James J. Thompson, Jr. To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION....................... ill TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................... v ABSTRACT........... vi INTRODUCTION................. 2 CHAPTER I. "OUR NOBLE, VENERABLE, REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": JOHN WITHERSPOON IN SCOTLAND, 1723-1768 . ............ 5 CHAPTER II. "AN EQUAL REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": WITHERSPOON IN NEW JERSEY, 1768-1776 37 NOTES . -

Civic Virtue in the American Revision of Rome

Critique: a worldwide student journal of politics Civic Virtue in the American Revision of Rome Sydney Smith The University of Texas at Austin 1 Spring 2019 The Roman Republic and the American Republic are often compared to show how the American Constitution built on the structures designed for the ancient era. However, there are also important differences between how the two republics function. Although the Americans and the Romans share the same fundamental republican values, and even many of the same governmental structures, they differ on the modes and means of sustaining republican ideals. The Romans genuinely believe in themselves and their ability to sustain civic virtues through the collective strength of deeply inculcated individual understanding. American constitution makers invoke a purported civic spirit the Romans embodied, while actually relying on the crafted structures that the new constitution creates. The Romans believe in themselves, while the American believe in their system. Americans neither completely emulate nor completely reinvent the Roman model. In their repeated invocations of Rome, the American constitution makers both adopt and revise Roman insights. To develop this basic contrast between Roman and American constitutional understandings, I compare the ancient era accounts of the founding of the Roman Republic in Livy’s History of Rome and Polybius’ The Rise of the Roman Empire to the modern era accounts in The Federalist and the Anti-Federalist essays by “Brutus.” Some invocations of Rome in contemporary political accounts neglect the differences between ancient and modern understandings of political virtue, while others question the importance of comparing contemporary America to Rome. -

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin 25

YPi AAAAAAJL 'imjij i=W AurCS'.ORAPHYOF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN t: > ' '^ \^^ -^ • ^JJ^I yfv Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/autobiographyofb00fran5 V Autobiography or Benjaa\in Tranklin Chicago W. B. CONKEY COMPANY THE IIW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY gG819^B ASTCR, LEN&X AND TfLOm HtfUNDAliONS B 1044 L LIFE or DR. FRANKLIN / My deab Sok, I HAVE amused myself with collecting some little anecdotes of my family. You may re- member the inquiries I made, when you were with me in England, among such of my rela- tions as were then living ; and the journey J undertook for that purpose. To be ac- quainted with the particulars of my parent- age and life, many of which are unknown to you, I flatter myself will afford the same pleasure to you as to me. I shall relate them upon paper : it will be an agreeable employ- ment of a week's uninterrupted leisure, which I promise myself during my present retire- ment in the country. There are also other motives which induce me to the undertaking. 4 3YS5 a 4 LI Ft: OF DR.. FRANKLIlSf. From the bosom of poverty and obscurity, in which I drew my first breath, and spent my earliest years, I have raised myself to a state of opulence and to some degree of celebrity in the world. A constant good fortune has attended me through every period of life to my present advanced age ; and my descend- ants may be desirous of learning what were the means of which I made use, and which, thanks to the assisting hand of Providence, have proved so eminently successful. -

Religion As a Virtue: Thomas Aquinas on Worship Through Justice, Law

RELIGION AS A VIRTUE: THOMAS AQUINAS ON WORSHIP THROUGH JUSTICE, LAW, AND CHARITY Submitted by Robert Jared Staudt A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorate in Theology Director: Dr. Matthew Levering Ave Maria University 2008 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE: THE CLASSICAL AND PATRISTIC TRADITION CHAPTER TWO: THE MEDIEVAL CONTEXT CHAPTER THREE: WORSHIP IN THE WORKS OF ST. THOMAS AQUINAS CHAPTER FOUR: JUSTICE AS ORDER TO GOD CHAPTER FIVE: GOD’S ASSISTANCE THROUGH LAW CHAPTER SIX: TRUE WORSHIP IN CHRIST CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY ABBREVIATIONS 2 INTRODUCTION Aquinas refers to religion as virtue. What is the significance of such a claim? Georges Cottier indicates that “to speak today of religion as a virtue does not come across immediately as the common sense of the term.”1 He makes a contrast between a sociological or psychological evaluation of religion, which treats it as “a religious sentiment,” and one which strives for truth.2 The context for the second evaluation entails both an anthropological and Theistic context as the two meet within the realm of the moral life. Ultimately, the study of religion as virtue within the moral life must be theological since it seeks to under “the true end of humanity” and “its historic condition, marked by original sin and the gift of grace.”3 Aquinas places religion within the context of a moral relation to God, as a response to God’s initiative through Creation and 4 Redemption. 1 Georges Cardinal Cottier. “La vertu de religion.” Revue Thomiste (jan-juin 2006): 335. 2 Joseph Bobik also distinguished between different approaches to the study of religion, particularly theological, philosophical, and scientific, all of which would give different answers to the question “what is religion?.” Veritas Divina: Aquinas on Divine Truth: Some Philosophy of Religion. -

From the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition Person, Nature, & Human Flourishing Aquinas College, Nashville, Tennessee March 9, 2020

From The Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition Person, Nature, & Human Flourishing Aquinas College, Nashville, Tennessee March 9, 2020 NOTE: To check the footnotes, please refer to a printed copy of the Catechism or an on-line version. THE VIRTUES 1803 "Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things."62 A virtue is an habitual and firm disposition to do the good. It allows the person not only to perform good acts, but to give the best of himself. The virtuous person tends toward the good with all his sensory and spiritual powers; he pursues the good and chooses it in concrete actions. The goal of a virtuous life is to become like God.63 I. THE HUMAN VIRTUES 1804 Human virtues are firm attitudes, stable dispositions, habitual perfections of intellect and will that govern our actions, order our passions, and guide our conduct according to reason and faith. They make possible ease, self-mastery, and joy in leading a morally good life. The virtuous man is he who freely practices the good. The moral virtues are acquired by human effort. They are the fruit and seed of morally good acts; they dispose all the powers of the human being for communion with divine love. The cardinal virtues 1805 Four virtues play a pivotal role and accordingly are called "cardinal"; all the others are grouped around them. They are: prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance.