Submission Guidelines Collaborate with Your Team on Your Case Study Presentation. When It Is Complete, the Team Leader Is Respon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nicolas Lamoignon De Basville, Intendant Du Languedoc De 1685 À 1718 : Une Longévité Rare

Académie des Sciences et Lettres de Montpellier 1 Séance du 16 novembre 2020 Nicolas Lamoignon de Basville, intendant du Languedoc de 1685 à 1718 : une longévité rare Valdo PELLEGRIN Maître de conférences honoraire à l’Université de Montpellier MOTS-CLÉS : Lamoignon de Basville, intendant, Montpellier, Louis XIV, monuments, dragonnades, camisards, Brousson. RÉSUMÉ : L’intendant Nicolas Lamoignon de Basville (1648-1724) réside à Montpellier de 1685 à 1718 dans l’hôtel d’Audessan. Après une description de cet hôtel nous évoquons la jeunesse, les études de Basville, son mariage et ses amitiés parisiennes, puis ses débuts comme avocat au parlement de Paris et sa nomination comme intendant du Poitou. En 1685, il est nommé par le roi intendant du Languedoc à la suite d’Henri d’Aguesseau qui refuse de dragonner les protestants nombreux dans la province. Le roi lui confie comme mission prioritaire d’éradiquer le protestantisme en Languedoc. Basville aura à gérer le difficile conflit de la guerre des camisards et un débarquement anglais à Sète, en 1710. Sur le plan de l’urbanisme et de l’architecture, il supervise la construction de la porte du Peyrou et l’installation de la statue équestre de Louis XIV quelques semaines avant son départ à la retraite en 1718. Mais jusqu’au bout, Basville n’a rien perdu de sa combativité contre les protestants. C’est lui qui a inspiré en 1724, année de sa mort, l’édit de Louis XV redoublant de sévérité vis-à-vis des protestants. L’histoire retiendra surtout la lutte implacable de Basville vis-à-vis des protestants du Languedoc. -

From Oppression to Freedom

FROM OPPRESSION TO FREEDOM John Jay and his Huguenot Heritage The Protestant Reformation changed European history, when it challenged the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century. John Calvin was a French theologian who led his own branch of the movement. French Protestants were called Huguenots as a derisive Conflict Over the term by Catholics. Protestant Disagreements escalated into a series of religious wars Reformation in seventeenth-century France. Tens of thousands of Huguenots were killed. Finally, the Edict of Nantes was issued in 1598 to end the bloodshed; it established Catholicism as the official religion of France, but granted Protestants the right to worship in their own way. Eighty-seven years later, in 1685, King Louis XIV issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, which reversed the Edict of Nantes, and declared the public practice of Protestantism illegal. Louis regarded religious pluralism as an obstacle to his achieving complete power over the French people. By his order, Huguenot churches were demolished, Huguenot schools were The Revocation of closed, all newborns were required to be baptized as Roman Catholics, and it became illegal for the the Edict of Nantes Protestant laity to emigrate or remove their valuables from France. A View of La Rochelle In La Rochelle, a busy seaport on France’s Atlantic coast, the large population of Huguenot merchants, traders, and artisans there suffered the persecution that followed the edict. Among them was Pierre Jay, an affluent trader, and his family. Pierre’s church was torn down. In order to intimidate him into converting to Catholicism, the government quartered unruly soldiers called dragonnades in his house, to live with him and his family. -

Introduction

Introduction The Other Voice [Monsieur de Voysenon] told [the soldiers] that in the past he had known me to be a good Catholic, but that he could not say whether or not I had remained that way. At that mo- ment arrived an honorable woman who asked them what they wanted to do with me; they told her, “By God, she is a Huguenot who ought to be drowned.” Charlotte Arbaleste Duplessis-Mornay, Memoirs The judge was talking about the people who had been ar- rested and the sorts of disguises they had used. All of this terrified me. But my fear was far greater when both the priest and the judge turned to me and said, “Here is a little rascal who could easily be a Huguenot.” I was very upset to see myself addressed that way. However, I responded with as much firmness as I could, “I can assure you, sir, that I am as much a Catholic as I am a boy.” Anne Marguerite Petit Du Noyer, Memoirs The cover of this book depicting Protestantism as a woman attacked on all sides reproduces the engraving that appears on the frontispiece of the first volume of Élie Benoist’s History of the Edict of Nantes.1 This illustration serves well Benoist’s purpose in writing his massive work, which was to protest both the injustice of revoking an “irrevocable” edict and the oppressive measures accompanying it. It also says much about the Huguenot experience in general, and the experience of Huguenot women in particular. When Benoist undertook the writing of his work, the association between Protestantism and women was not new. -

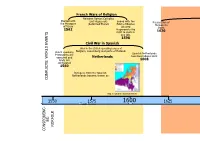

Refugee Timeline for Workshop

French Wars of Religion Between Roman Catholics Started with and Huguenots Ended with the the Massacre Persecution of (Reformed French Edict of Nantes Huguenots of Vassy Allowed starts 1562 Hugeneouts the 1620 right to work in any job. 1598 Civil War in Spanish War in the Dutch speaking areas of Belgium, Luxemburg and parts of Holland. Dutch speaking Spanish Netherlands Protestants are becomes independent executed and Netherlands lands are 1608 confiscated 1560 Refugees from the Spanish Netherlands became known as CONFLICTS: WORLD EVENTS Map showing the Spanish Nether- 1550 1575 1600 1625 Tudor Period ES: NORFOLK CONSEQUENC- French Persecution of Huguenots (Reformed French Protestants) The Dragonnades King Louis XIV of France encouraged soldiers to abuse French Protestants and destroy or steal their possessions. He wanted Huguenot families to leave France or convert to Catholicism. Edict of Fontainebleau Louis IX of France reversed the Edict of Nantes which stopped religious freedom for Protestants. 1685 King Louis XIV France French Flag before the French Revolution 1650 1675 170 1725 1750 1775 Stuart Period Russian persecution Ends with the Edict of of Jews Versailles which The Italian Wars of allowed non-Catholics to practice their Started with the May Laws. religion and marry Independence 1882 without becoming Jews forced to Catholic Individual states become live in certain 1787 independent from Austria and unite areas and not allowed in specific schools French Revolution or to do specific jobs. Public rebelled against the king and religious leaders. Resulted in getting rid of the King 1789-99 French Flag after the French Revolution Individual states which form 1775 1800 1825 1850 1875 1900 Georgian Period Victorian Period Russian persecution Second World War Congolese Wars Syrian Civil Global war involved the vast Repeal of the May Conflict involving nine African War majority of the world's nations. -

The Festival of Britain 1951

BANK OF ENGLAND ISSUED BY THE COURT OF DIRECTORS ON THE OCCASION OF THE FESTIVAL OF BRITAIN 1951 Bank of England Archive (E6/8) The Bank of England completed III I939 to the design of Sir Herbert Baker Bank of England Archive (E6/8) [Copyright BUII/� 0/ Ellglalld HE BANK OF ENGLAND came into being to provide funds for the T war that was being fought between 1689 and 1697 by William III against Louis XIV of France. In return for a loan of £1,200,000 to the King the subscribers, who numbered 1,272, were granted a Royal Charter on the 27th July, 1694, under the title " The Governor and Company of the Bank of England ". The Bank of England Act of I 946 brought the Bank into public ownership, of the but provided for the continued existence of the " Governor and Company ; Bank of England " under Royal Charter. The affairs of the Bank are administered by the Court of Directors, appointed by the King and comprising a Governor and Deputy Governor, each appointed for five years, and 16 Directors, each appointed for four years. The Court may appoint four of their members as Executive· . Directors, who, together with the senior officials and a number of specialists as advisers, assist the Governors in the day-ta-day management of the Bank. Over the years the Bank of England has become the " bankers' bank ". and banker to the Government. The description " bankers' bank" indicates that the principal banks in the United Kingdom deposit with it their reserves of cash. -

An Efficient System of Espionage Which, A

ORGANIZA TION OF THE REFORMED CHURCH 27 an efficient system of espionage which, a decade later, smashed the Cinq-Mars conspiracy and incidentally gave Sedan to France; by the creation of provincial intendants in 1637 with overriding financial, judicial and police powers, and responsible to the king and his chief minister alone; and by a steady process of attrition, aided by the sale of offices, which gradually transformed the feudal aristocracy into a noblesse de cour lacking real influence and dependent on the monarchy for continued favours.2 In foreign policy, Richelieu turned the Thirty Years' War into a contest between Bourbon and Hapsburg, and with Protestant help gave France a new Rhine frontier. In the struggle with Spain, the king’s chief officer of state was able to secure the Pyrenees border and gain a foothold in northern Italy.3 This was Mazarin’s inheritance after Richelieu's death in 1642. On the European front, with the aid of the young Conde against the Spaniards at Rocroi and with that of the Protestant Turenne in Germany, he gained for France a leading place in Europe in the years following the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. The war with Spain continued until the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659, after France, with Cromwell’s support, had successfully invaded the Spanish Netherlands. At this treaty, the Pyrenean border was finally determined and the province of Artois ceded by Spain, thus providing the French with an additional barrier to foreign incursions in the vulnerable north-east.4 At home, Mazarin’s pressing need to finance an aggressive foreign policy sparked off the series of civil wars from 1648 until 1652 known collectively as the Fronde. -

David Garrioch, Protestants and Bourgeois Notability in Eighteenth-Century Paris

Protestants and Bourgeois Notability 1 Protestants and Bourgeois Notability in Eighteenth-Century Paris David Garrioch Until the second half of the seventeenth century, Protestants in Paris participated in many aspects of city life alongside their Catholic peers. They were admitted to the trade guilds and to the learned academies, and many held administrative and venal offices. They served in the Parliament and other leading institutions, and some were accepted in fashionable salons.1 This began to change after Louis XIV’s assumption of personal power in 1661, as the Royal Council progressively excluded Huguenots (as French Reformed Protestants were called) from many occupations, especially the most prestigious ones. The process culminated with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, after which a series of laws denied civil rights to Huguenots and required them to convert to Catholicism. Nearly all the Paris Huguenots, threatened with legal sanctions, arbitrary imprisonment, and with dragonnades like those taking place in the provinces, signed abjurations. Many, however, maintained their Protestant faith in private, praying and reading the Bible within their families. They rarely attended Catholic religious services. Although at first there were periodic attempts to enforce Catholic practice, after 1710 the Paris authorities largely turned a blind eye to the Protestant presence. The police only intervened if there were complaints from Catholics, or what they David Garrioch is Professor of History at Monash University, Australia. He has written on eighteenth- century Paris, on early modern European towns and on the Enlightenment, notably on friendship, philanthropy and cosmopolitanism. His most recent book is The Huguenots of Paris and the Coming of Religious Freedom, 1685-1789 (Cambridge: 2014). -

Roger L'estrange and the Huguenots: Continental Protestantism and the Church of England

Roger L’Estrange and the Huguenots: Continental Protestantism and the Church of England Anne Dunan-Page To cite this version: Anne Dunan-Page. Roger L’Estrange and the Huguenots: Continental Protestantism and the Church of England. Anne Dunan-Page et Beth Lynch. Roger L’Estrange and the Making of Restoration Culture, Ashgate, pp.109-130, 2008, 978-0-7546-5800-9. halshs-00867280 HAL Id: halshs-00867280 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00867280 Submitted on 27 Sep 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHAPTER SIX Roger L’Estrange and the Huguenots: Continental Protestantism and the Church of England1 Anne Dunan-Page, University of Montpellier At the end of October 1680, Roger L’Estrange disappeared from his London home. Traversing muddy roads and wintry seas, he first joined the duke of York in Edinburgh and then set sail for The Hague. There he informed Thomas Ken, the almoner of the Princess of Orange and the future bishop of Bath and Wells, that he intended to take communion at Ken’s Anglican service.2 This was one way to escape charges of crypto-catholicism.3 Another was to make himself scarce. -

Archives Des Consistoires Tt/230 À 276/B

ARCHIVES DES CONSISTOIRES TT/230 à 276/B Inventaire par Édith Thomas et Paul Geisendorf Revu par Brigitte Schmauch Édition 2013 INTRODUCTION Dates : [1317, 1446] 1520-1740. Importance matérielle : 52 articles (environ 20 ml), cotés TT/230 à 276/B. Modalités d’entrée : Prise en charge à la Révolution, avec les archives du secrétariat d’État de la Maison du roi au sein duquel les affaires des protestants – appelés « religionnaires » c'est à dire adeptes de la « religion prétendue réformée » selon l’expression alors utilisée et abrégée en « R. P. R. » – devinrent un bureau en 1749. Conditions d’accès : Consultation sous forme de microfilms. Historique du producteur. La majorité des archives conservées sous ces cotes nous sont parvenues par l’intermédiaire de l’administration royale mais proviennent des églises réformées de France, d’où le nom d’« archives des consistoires » sous lequel on les désigne couramment. L’histoire de ces églises sous l’Ancien Régime s’articule principalement autour de trois dates : 1598 (édit de Nantes), 1685 (révocation de l’édit de Nantes par l’édit de Fontainebleau), 1787 (édit de tolérance). À une période d’expansion informelle de la réforme en France au cours de la première moitié du XVIe s. succède une phase d’institutionnalisation, fondée sur la Discipline votée par le synode de Paris en 1559 et marquée par la mise en place d’églises régulièrement constituées qui se fédèrent sous l’égide de Calvin (organisation dite « synodo-presbytérale »). L’édit de Nantes, promulgué par Henri IV en 1598 pour établir une paix durable entre catholiques et protestants, contingente par ailleurs assez strictement les lieux d’exercice du culte. -

Bank of England: a Rough Sketch

Journal of Accountancy Volume 49 Issue 2 Article 2 2-1930 Bank of England: A Rough Sketch Walter Mucklow Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jofa Part of the Accounting Commons Recommended Citation Mucklow, Walter (1930) "Bank of England: A Rough Sketch," Journal of Accountancy: Vol. 49 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jofa/vol49/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Accountancy by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Bank of England A ROUGH SKETCH By Walter Mucklow “Benk! Benk! Benk!” One evening, when looking over some English newspapers, I could have sworn that I heard this cry as I came across a picture showing the additions which were to be made to the fabric of the Bank of England, and suddenly I felt as if I had been transported three thousand miles, carried backwards for a little more than a generation and all my senses brought successively into intense activity. I could see the crowded streets on a week day, the deserted spaces on a London Sunday. I could taste the smoke of a No vember fog which shut out all sights. I could feel the push of passers-by rushing for a bus. I could smell the pavement on a hot August afternoon. But above all, more insistent than all, I heard the bus conductor standing on his small step, hanging on to his leather strap or slapping the side of the bus with it as a sign to the driver to go on, and calling “Benk! Benk! Benk!” “Newgate, Cheapside, Benk!” “City road, Moorgate street, Benk!” “Bishopgate street, Cornhill, Benk!” From all directions north of the river the bus lines seemed to end at the “benk” and the busses, having reached that terminus, set forth again and used it as a starting point. -

Appolo Study Centre

APPOLO STUDY CENTRE GENERAL AWARENESS PRACTICE MCQs FOR BANK EXAMINATIONS 2014 1. Who headed the committee which submitted its report on February 7, 2014 regarding Financial Bench Marks (appointed by RBI)? a) Prakash Bakshi b) Damodaran c) Vijaya Bhaskar d) D.Subba Rao e) None of the above 2. Which among the following is correct and full form of CAS in context with banking markets in India? a) Cash Authorized Scheme b) Credit Authorized Scheme c) Credit Access Systemd) Credit Arrangement System e) Cash Accreditation Scheme 3. Money laundering refers to which of the following? a) Conversion of assets into cash b) Conversion of Black money gained from illegal activities to white money c) Conversion of cash into gold d) Conversion of gold into cash e) Conversion of shares into cash 4. Account for conversion of physical securities into electronic form is know as? a) NRI Account b) Foreign Account c) Trio Account d) Current Account e) DEMAT (Dematerialisation)Account 5. What is "Hot Money"? a) Flow of funds (or capital) from one country to another in order to earn a short-term profit on interest rate differences and/or anticipated exchange rate shifts. b) Hard Currency c) Soft Currency d) Foreign Assets e) All of these 6. RBI has decided to prescribe a minimum CRAR for StCBS /CCBs of 9% to be achieved in a phased manner over a period of 3 years as indicated below a) 3 years b) 4 years c) 5 yeasrs d) 2 years e) No such restriction 7. PFRDA stands for? a) Provident Fund Regulatory and Development Authority b) Preferential Fund Regulatory and Development Authority c) Permanent Fund Regulatory and Development Authority d) Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority e) None of these PH: 24339436, 42867555, 9840226187 8. -

A Study of the Huguenots in Colonial South Carolina, 1680-1740

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 The Evolution Of French Identity: A Study Of The Huguenots In Colonial South Carolina, 1680-1740 Nancy Maurer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Maurer, Nancy, "The Evolution Of French Identity: A Study Of The Huguenots In Colonial South Carolina, 1680-1740" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 847. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/847 THE EVOLUTION OF FRENCH IDENTITY: A STUDY OF THE HUGUENOTS IN COLONIAL SOUTH CAROLINA, 1680-1740 by NANCY LEA MAURER A.A. Valencia Community College B.A. University of Central Florida A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Science at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 ©2006 Nancy Lea Maurer ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the changes that occurred in the French identity of Huguenot immigrants to colonial Carolina. In their pursuit of prosperity and religious toleration, the Huguenots’ identity evolved from one of French religious refugees to that of white South Carolinians. How and why this evolution occurred is the focus of this study.