Appendix 6: Cultural Resources Supporting Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improvements to Powell Street Station Are Included As Part of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency's Mid-Market Plan. This H

POWELL STREET PLANNING Improvements to Powell Street Station are included as part of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency’s Mid-Market Plan. This has been enhanced by the recommended improvements to Hallidie Plaza that were identified in the 2004 charrette funded in part by the owners of the soon-to- open (2006) Bloomingdale’s at San Francisco Center. Planning is also underway to make best use of the station space, which was studied in the 2004 Capacity Plan and found to be constricted in key areas (near the BART Police facility, in the mezzanine corridor between the fare gate areas, etc.) which may be affected when and if Muni’s Central Subway is connected to BART at this station. The Muni Central Subway project is proposed to connect to Powell station and to the new Transbay Terminal Project. The Powell station was studied in 2004 to analyze the critical areas of platform capacity, vertical circulation (stairs/escalators) capacity, and fare gate capacity. DEVELOPMENT BART is negotiating special entrance agreements with Forest City Development for a Bloomingdale’s entrance and with Millennium Partners and San Francisco Redevelopment Agency to consider what will become of the “tunnel” space between the station and and Yerba Buena Center. Owners of the Flood Building are also working with BART staff to address the possibilities of sub-street connections to the station. The Four Seasons high-rise tower, containing 150 housing units, 100 long-term hotel suites and 250 hotel rooms, is directly adjacent to the station and opened in 2002. Construction is underway at the adjacent Mexican Museum and the Jewish Museum in Yerba Buena Center. -

Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold

SEDGWICK, DETERT, MORAN & ARNOLD NICHOLAS W. HELDT (Bar No. 083601) 2 DIANE T. GORCZYCA (Bar No. 201203) One Embarcadero Center, 16th Floor 3 San Francisco, CA 94111-3628 Telephone: (415) 781-7900 4 Facsimile: (415) 781-2635 5 Attorneys for Defendant RSR WHOLESALE GUNS, INC. 6 7 8 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 9 FOR THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO 10 11 THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ) CASE NO. 303753 CALIFORNIA, et aI., ) 12 ) RSR WHOLESALE GUNS, INC.'S Plaintiffs, ) RESPONSES TO PLAINTIFFS' FIRST 13 ) SET OF FORM INTERROGATORIES vs. ) 14 ) ARCADIA MACHINE & TOOL, et aI., ) 15 ) Defendants. ) 16 ) 17 18 PROPOUNDING PARTY: Plaintiffs PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 19 RESPONDING PARTY: Defendant RSR WHOLESALE GUNS, INC. 20 SET NUMBER: ONE (1) 21 Defendant RSR WHOLESALE GUNS, INC. (hereinafter "RSR" or 22 "Defendant") responds to Plaintiffs' First Set of Form Interrogatories as follows: 23 FORM INTERROGATORY NO. 1.1: 24 State the name, ADDRESS, telephone number, and relationship to you of each 25 PERSON who prepared or assisted in the preparation of the responses to these interrogatories. 26 (Do not identify anyone who simply typed or reproduced the response.) SEDGWICK. 27 RESPONSE TO INTERROGATORY NO. 1.1: DETERT. MORAN & ARNOLD 28 The responses to these interrogatories were prepared by outside counsel to One Embarcadero Center Sixteenth Floor San F..... ci.sco, California 94111.,'!628 - 1 - TeL 415. 781 . 7900 PRO-SF/51086 RSR WHOLESALE GUNS, INC.'S RESPONSES TO PLAINTIFFS' FIRST SET OF FORM INTERROGATORiES RSR, Nicholas W. Heldt and Diane T. Gorczyca of Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold, based 2 on infonnation provided by RSR's Senior Vice President and in-house legal counsel, Michael 3 Saporito. -

BANCROFTIANA Number 145 • University of California, Berkeley • Fall 2014

Newsletter of The Friends of The Bancroft Library BANCROFTIANA Number 145 • University of California, Berkeley • Fall 2014 CALIFORNIA Captured On Canvas alifornia Captured on Canvas represents a first for The John superseded John Singer Sargent as the most important CBancroft Library Gallery. The exhibit focuses exclu- and fashionable portrait painter in England. As famous for sively on the Pictorial Collection’s more than 300 paintings. his bohemian life as he was for his bravura portraits, John With the exception of the 120 framed works in the Robert is said to have been the model for Alec Guinness’s character B. Honeyman, Jr. Collection of Early Californian and West- Gulley Jimson in the film The Horse’s Mouth. (Interestingly, ern American Pictorial Material—acquired by the Friends of John painted both T. E. Lawrence’s and King Faisal’s por- The Bancroft Library and the UC Regents in 1963—most of traits. Alec Guinness portrayed Faisal in David Lean’s epic the impressive array of framed works in the Pictorial Collec- film, Lawrence of Arabia.) tion are the result of individual donations or transfers from The inclusion of John Sackas’s colorful paintings collections acquired by gift or purchase. These works range documenting the Golden Gate Produce Market in the late not only in subject matter and geography—portraits from 1950s, before it was torn down in 1962 to make way for the Mexico, landscapes of Utah and the American Southwest— Embarcadero Center, and a study for a mural by Carleton but they also vary in medium from delicate pencil sketches, Lehman, painted on the verso of his portrait of Inez Ghi- watercolors, gouaches, ink and wash drawings, engravings, rardelli, expands the scope of this exhibition beyond the hand-colored lithographs, and photographs to oils on Continued on page 4 canvas, board, and paper. -

SFBAPCC January 2019 Postcard Newsletter

See newsletters in color at www.postcard.org Our name re�ects our location not our only area of interest. San Francisco Bay Area Post Card Club January 2019 Meeting: Saturday, January 26, 11 :00AM to 3:00 PM Vol. XXXIV, No. 1 Ebenezer Lutheran Church, Mural Hall Browsing and Trading, 11 :30AM to 1:30PM - Meeting begins at 1:30PM San Francisco • Cover Card: Entrance to Confusion Hill? Visitors and dealers always welcome. IN • Meetin g Minutes Meeting Schedule on back cover. THIS • Kathryn Ayers "Lucky Baldwin" Program ISSUE Omar Kahn "Paper Jewels" Program PROGRAM: The Saturday, January 26 San Francisco Bay Area Post Card Club meeting is from 11am to 3pm at Ebenezer Lutheran Church, Mural Hall (entrance off lower parking lot), 678 Portola Drive, San Francisco 94127. The meeting will be called to order at 1pm and the program will follow. (club meetings will be back at Fort Mason in February. Postcards and Space-Time Defy gravity at MYSTERY SPOTS across the US! Santa Cruz vortex is just one of many. Physics and the space-time continuum are turned upside down as the enigma of multidimensional reality is revealed in Daniel Saks presentation. LOCATION INFORMATION: Ebenezer Lutheran Church in Mural Hall The entrance to Mural Hall is off of the lower parking lot. 2 CLUB OFFICERS President: Editor: ED HERNY, (415) 725-4674 PHILIP K. FELDMAN, (310) edphemra(at)pacbell.net 270-3636 sfbapcc(at)gmail.com Vice President: Recording Secretary: NANCY KATHRYN AYRES, (415) 583-9916 REDDEN, (510) 351-4121 piscopunch(at)hotmail.com alonestar(at)comcast.net Treasurer/Hall Manager: Webmaster: ED CLAUSEN, (510) 339-9116 JACK DALEY: daley(at)postcard.org eaclausen(at)comcast.net MINUTES, October 20, 2018 Call to Order: The club meeting was called to order by President Ed Herny at 1:30 pm on the 20th of Oct. -

A 18-031 SFPD Update to the S.F. Community Justice Center (CJC)

A 18-031 02/20/18 SFPD Update to the S.F. Community Justice Center (CJC) The Community Justice Center (CJC) began hearing cases on Monday, March 2, 2009 with certain Tenderloin misdemeanor citations. The purpose of this court is to refer defendants into a service that will make a positive change to his or her behavior.' Central, Southern, Northern, and Tenderloin Stations are within the designated geographical area that can refer cases to CJC court. The region of the CJC is 'bordered by Bush Street on the north, Kearny and Third Streets on the east, Harrison Street on the south, and Otis and Gough Streets on the west. See attachment for the range of addresses within the CJC District. Central, Southern, Northern, and Tenderloin Commanding Officers, shall designate a liaison on their staff who will deliver all appropriate cases, share BWC video through Evidence.com links, monitor all case dispositions, and forward the dispositions to the' citing officer. CJC court is held Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday afternoons at 2:00 p.m. at 575 Polk Street. Defendants should be cited to any of these days and this specific time. No defendant should be cited for a Friday as court is not in session,. CJC booking staff are required to receive rebooking packages and original citations 7 days before a defendant's court date. Defendants should be given a court date that is at least 8 and no more than 10 court days (not including weekends) after the citation is issued. Example: If a date of 8 court days from the date of the citation is given, then the completed rebooking packet shall be delivered the next business day. -

SAN FRANCISCO 2Nd Quarter 2014 Office Market Report

SAN FRANCISCO 2nd Quarter 2014 Office Market Report Historical Asking Rental Rates (Direct, FSG) SF MARKET OVERVIEW $60.00 $57.00 $55.00 $53.50 $52.50 $53.00 $52.00 $50.50 $52.00 Prepared by Kathryn Driver, Market Researcher $49.00 $49.00 $50.00 $50.00 $47.50 $48.50 $48.50 $47.00 $46.00 $44.50 $43.00 Approaching the second half of 2014, the job market in San Francisco is $40.00 continuing to grow. With over 465,000 city residents employed, the San $30.00 Francisco unemployment rate dropped to 4.4%, the lowest the county has witnessed since 2008 and the third-lowest in California. The two counties with $20.00 lower unemployment rates are neighboring San Mateo and Marin counties, $10.00 a mark of the success of the region. The technology sector has been and continues to be a large contributor to this success, accounting for 30% of job $0.00 growth since 2010 and accounting for over 1.5 million sf of leased office space Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 2012 2012 2012 2013 2013 2013 2013 2014 2014 this quarter. Class A Class B Pre-leasing large blocks of space remains a prime option for large tech Historical Vacancy Rates companies looking to grow within the city. Three of the top 5 deals involved 16.0% pre-leasing, including Salesforce who took over half of the Transbay Tower 14.0% (delivering Q1 2017) with a 713,727 sf lease. Other pre-leases included two 12.0% full buildings: LinkedIn signed a deal for all 450,000 sf at 222 2nd Street as well 10.0% as Splunk, who grabbed all 182,000 sf at 270 Brannan Street. -

D D D D D D D D D

File No. -------17068 Item No.10------- SUNSHINE ORDINANCE TASK FORCE AGENDA PACKET CONTENTS LIST =S=O....:.T..:....F_-......:C=o=m=p=la=in..:..:t:.....;:C:;..;:o=m=m=itt=e..;;;;..e_______ Date: July 25, 2017 ~ Petition/Complaint Page:_f D Memorandum - Deputy City Attorney Page:_ D Complainant's Supporting Documents Page:_ ~ Respondent's Response Page:s]o D Correspondence Page:_ D Order of Determination Page:_ D Minutes Page:_ D Committee Recommendation/Referral Page:_ D Administrator's Report Page:_._ D No Attachments OTHER D D D D D D D D D Completed by: __V_. Y_o_u_n_g ______Date 07/21/17 *An asterisked item represents the cover sheet to a document that exceeds 25 pages. The complete document is in the file. P321 Sunshine Ordinance Task Force Complaint Summary File No. 17068 Ann Treboux V. Arts Commission Contacts information (Complainant information listed first): [email protected] (Complainant) Kate Patterson, Arts Commission (Respondent) File No. 17067: Complaint filed by Ann Treboux against the Arts Commission, for allegedly violating Administrative Code (Sunshine Ordinance), Section 67.25, by failing to respond to an Immediate Disclosure Request in a complete manner. Administrative Summary if applicable: Complaint Attached. P322 Young, Victor From: atreboux1 [email protected] Sent: Thursday, June 08, 2017 3:29 PM To: SOTF, (BOS); Patterson, Kate (ART) Cc: [email protected] Subject: Re: Immediate Disclosure Request-please open a file and schedule a hearing. There is no PDF attachment in this response. I have some serious doubts as to what Kate Patterson's constant mistakes have to do with me. -

March 2006 GRACE N TES Vol

Grace Notes 1 March 2006 GRACE N TES Vol. 22, No. 3 March 2006 The Monthly Newsletter of the Memphis Scottish Society, Inc. Special Guest Speaker at March Meeting We are afforded a rare opportunity at this month’s member meeting. Dr. James P. Cantrell will address us on the subject of his newly released book How Celtic Culture Invented Southern Literature. Dr. Cantrell first sensed that the Celtic cultural heritage was the primary source of Southern culture while researching his master’s thesis. After learning the Gaelic and Cymric (Welsh variation) languages—in order to specialize in Irish literature while working toward his M.A. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—Dr. Cantrell recognized many surnames of Celtic origin common to his native Middle Tennes- see, a region primarily settled by immigrants from Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. Further reading about Celtic folk culture revealed social behavior similar to what he knew from his own upbringing in the hill country. Dr. Cantrell pursued his theory, despite surprisingly strong opposition from some academics, and found further evidence in the writings of many great Southern writers, including William Faulkner, Flannery O’Conner, Margaret Mitchell and Pat Conroy. How Celtic Culture Invented Southern Literature disproves the common perception, prevalent in American universities, that the culture of white Southerners springs from English, or Anglo-Norman, roots. Dr. Cantrell will autograph copies of his book purchased at the meeting ($29.95 plus tax). There will also be a signing at Davis Kidd on Thursday, March 16th from 6-8 pm. Be sure you plan to attend Monday, March 13th. -

Sobriety First, Housing Plus Meet the Man Who Runs a Homeless Program with a 93 Percent Success Rate and Why He Says Even He Couldn’T Solve San Francisco’S Crisis

Good food and drink Travel tips The Tablehopper says get ready for hops Bay Area cannabis tours p.18 at Fort Mason p.10 Visiting Cavallo Point — Susan Dyer Reynolds’s favorite things p.11 The Lodge at the Golden Anthony Torres scopes out Madrone Art Bar p.12 Gate p.19 MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 34TH YEAR VOLUME 34 ISSUE 09 SEPTEMBER 2018 Reynolds Rap Sobriety first, housing plus Meet the man who runs a homeless program with a 93 percent success rate and why he says even he couldn’t solve San Francisco’s crisis BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS Detail of Gillian Ayres, 1948, The Walmer Castle pub near Camberwell School of Art, with Gillian Ayres (center) hris megison has worked with the home- and Henry Mundy (to the right of Ayres). PHOTO: COURTESY OF GILLIAN AYRES less for nearly three decades. He and his wife, Tammy, helped thousands of men get off the Cstreets, find employment, and earn their way back into Book review: ‘Modernists and Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, society. But it was a volunteer stint at a winter emergency shelter for families where they saw mothers and babies Hockney and The London Painters,’ by Martin Gayford sleeping on the floor that gave them the vision for their organization Solutions for Change. The plan was far from BY SHARON ANDERSON tionships — artists as friends, as photographs and artworks, Gayford traditional: Shelter beds, feeding programs, and conven- students and teachers, and as par- draws on extensive interviews with tional human services were replaced with a hybrid model artin gayford’s latest ticipants who combined to define artists to build an intimate history of where parents worked, paid rent, and attended onsite book takes on the history painting from Soho bohemia in the an era. -

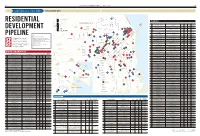

Residential Development Pipeline

36 SAN FRANCISCO BUSINESS TIMES JUNE 26, 2015 37 SAN FRANCISCO STRUCTURES SPECIAL REPORT Columbus Ave. The Embarcadero 52 SPONSORED BY Broadway Pacific Ave. Kearny St. PLANNED Stockton St. RESIDENTIAL Jackson St. Powell St. Montgomery St. SAN FRANCISCO Polk St. 80 Project name, address Developer Done Units Sale/ Market/ Sacramento St. rental affordable NP 1654 Sunnydale Ave. Mercy Housing California, Related Cos. 2018+ 1,700 both both 34 40 78 106 DEVELOPMENT 14 Pine St. 77 Potrero Terrace, 1095 Connecticut St. Bridge Housing Corp. 2018 1,400- both both California St. Bush St. 60 7 85 71 58 Sutter St. Spear St. 1,700 79 8 1 Main St. Mission Rock, Seawall Lot 227 and SWL 337 Associates LLC (S.F. Giants) 2017+ 1,500 TBD both Gough St. 112 35 80 5 Beale St. 72 Laguna St. 113 Webster St. Pier 48 38 Fremont St. Steiner St. Geary Blvd. 90 33 Pier 70 residential Forest City 2029 1,000- both both Divisadero St. 55 48 73 KEY 95 118 107 10 2,000 PIPELINE 2nd St. NP: Not placed; outside map area 96 Market St. 103 Van Ness Ave. 64 Ellis St. 62 61 74 700 Innes St. Build Inc. 2020 980 rent market Market: A majority of units are market rate, 29 94 1st St. Residential projects in 75 10 S. Van Ness Ave. Crescent Heights 2018+ 767 TBD market though almost all projects include some affordable Geary Blvd. Mission St. 97 San Francisco of 60 units units to comply with city regulations Turk St. 102 76 5M at Fifth and Mission Streets Forest City / Hearst Corp. -

870 Market St | Union Square

FLAGSHIP & BOUTIQUE RETAIL THE FLOOD BUILDING 870 Market St | Union Square At the heart of the city for over 100 years PROPERTY SUMMARY Union Square The Flood Building is one of San Francisco’s 26.2M best known landmarks and has been an VISITORS iconic destination for over a century. UNION SQUARE A HISTORICAL GEM Architecturally, the Flood Building hearkens back to the era of its birth. $10.2B Its turn of the century charm is especially evident in the dramatic IN SPENDING rounded rotunda that commands and dominates the corner of Powell UNION SQUARE and Market Streets. Every detail, from the tall storefronts that beckon to the baroque façade with its deep-chiseled windows, provides just enough ornamentation to enliven rather than clutter the scene. 19K IMPORTANT INTERSECTION DAILY PASSENGERS The Flood Building is situated on Powell and Market streets, next to the Demise to Suit POWELL ST CABLE CAR Powell St cable car turntable, Hallidie Plaza and the Powell St BART Station entrance where tourists, locals, theater goers, conventioneers, shoppers, cable car riders and daytime workforce all cross paths. Powell Street/BART station ridership averages over 250,000 debarkations daily and the Hallidie Plaza escalator which leads to the 10K Flood building is the primary entry and exit portal. PEDES TRIANS PER HOUR MARKET & POWELL Demise to Suit GROUND 500 SF up to 14,659 SF SECOND Up to 17,681 SF LOWER Up to 8,418 SF CO - TENANCY CO-TENANCY POWELLPOWELL ST ST POWELLPOWELLPOWELL ST ST ST ROTUNDA & MARKET ST ROTUNDAROTUNDA & & MARKET MARKET ST ST ROTUNDA & MARKET ST Education Education Education Education Crocker Galleria It’s not just a place to shop.. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE a CULTURAL EVENT for the DEAF a Graduate Project Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of Th

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE A CULTURAL EVENT FOR THE DEAF A graduate project submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Robert Irwin Roth May, 1983 The Graduate Project of Robert Irwin Roth is approved: California State University, Northridge ii Copyrighted by Robert Irwin Roth 1983 iii ~-------------------------------- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere appreciation and thanks to Paul Kravagna and Phil Morrison for their persistence and patience in guiding this paper to its completion. A special note of appreciation goes to Theresa B. Smith for her support during the Deaf Arts Festival, and since; and to my personal friends and family for their encouragement. iv I --------------------------------- TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNCMLEDGMENTS . iv LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . • • viii ABSTRACT ix Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • • 1 II. PLANNING AND PROCEDURE 8 Brainstorming • 10 Research • • • • 14 Time Line . • • 18 Event Content • • • . .. 18 Contract Persons, Places, and Ideas • 23 Finalize Activities . • • • 25 Delegation of Responsibilities • • • • • • 25 Installation • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 26 Clean-Up • • • • • . • • • • • • • . • • 26 Evaluation • • • • • • • • • • 26 III. THE CULTURAL EVENT: 1980 DEAF ARTS FESTIVAL • • • • 28 Publicity and Participants • • • 28 Educational Components • • • • 29 Art Exhibition • • • • • • • • • • 29 Performances • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 31 Special Photograph Exhibit • • • • • • • 31 Workshops . • • • • • • 32 Lectures and Panel Discussions • • • 32 Special Performances • • • • • 34 IV. CONCLUSION • • • • 35 REFERENCES • 42 v APPENDICES A. PUBLICITY MANUAL AND OTHER PRESS RELEASES • • • • • . 43 B. REPRINTS OF NEWSPAPER CLIPPINGS 65 C. SPECIAL EXHIBIT HANDOUT • • • • • • 74 D. APPLICATION FORMS AND MATERIALS 76 E. EVALUATION LETTERS FROM GUEST SPEAKERS 83 F. EVALUATION QUESTIONNAIRE 89 G. STUDENT MERIT CERTIFICATE . 91 H. 1980 DEAF ARTS FESTIVAL SCHEDULE (in back pocket) . 93 I.