TOCC0280DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Booklet

SUOMI – FINLAND 100 A CENTURY OF FINNISH CLASSICS SUOMI – FINLAND 100 A CENTURY OF FINNISH CLASSICS CD 1 74:47 FINNISH ORCHESTRAL WORKS I Jean Sibelius (1865–1957) 1 Andante festivo (1922, orch. Jean Sibelius, 1938) 3:44 Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra & Leif Segerstam, conductor Robert Kajanus (1856–1933) 2 Overtura sinfonica (1926) 9:10 Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra & Leif Segerstam, conductor Leevi Madetoja (1887–1947) 3 Sunday Morning (Sunnuntaiaamu) from Rural Pictures (Maalaiskuvia), Op. 77 (1936) [From music to the filmBattle for the House of Heikkilä] 4:20 Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra & John Storgårds, conductor Ernest Pingoud (1887–1942) 4 Chantecler (1919) 7:33 Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra & Sakari Oramo, conductor Väinö Raitio (1891–1945) 5 Fantasia poetica, Op. 25 (1923) 10:00 Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra & Jukka-Pekka Saraste, conductor 2 Uuno Klami (1900–1961) 6 Karelian Rhapsody (Karjalainen rapsodia), Op. 15 (1927) 14:24 Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra & Sakari Oramo, conductor Erkki Melartin (1875–1937) Music from the Ballet The Blue Pearl (Sininen helmi), Op. 160 (1928–30) 7 II. Entrée avec pantomime 4:00 8 VIII. Scène (Tempête) 2:32 9 XIV. Pas de deux 3:07 Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra & Hannu Lintu, conductor Aarre Merikanto (1893–1958) 10 Intrada (1936) 5:40 Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra & Leif Segerstam, conductor Uuno Klami (1900–1961) 11 The Forging of the Sampo (Sammon taonta) from the Kalevala Suite (1943) 7:24 Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra & John Storgårds, conductor Einar Englund (1916–1999) 12 The Reindeer Ride (Poroajot) (1952) Music from the filmThe White Reindeer (Valkoinen Peura) (1952) 1:24 Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra & Leif Segerstam, conductor 3 CD 2 66:42 FINNISH ORCHESTRAL WORKS II Heikki Aaltoila (1905–1992) 1 Wedding Waltz of Akseli and Elina (Akselin ja Elinan häävalssi) (1968) 3:53 Music from the filmUnder the North Star (Täällä Pohjantähden alla) Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra & John Storgårds, conductor Aulis Sallinen (b. -

KONSERTTIELÄMÄ HELSINGISSÄ SOTAVUOSINA 1939–1944 Musiikkielämän Tarjonta, Haasteet Ja Merkitys Poikkeusoloissa

KONSERTTIELÄMÄ HELSINGISSÄ SOTAVUOSINA 1939–1944 Musiikkielämän tarjonta, haasteet ja merkitys poikkeusoloissa Susanna Lehtinen Pro gradu -tutkielma Musiikkitiede Filosofian, historian ja taiteiden tutkimuksen osasto Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto Lokakuu 2020 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Humanistinen tiedekunta / Filosofian, historian ja taiteiden tutkimuksen osasto Tekijä – Författare – Author Susanna Lehtinen Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Konserttielämä Helsingissä sotavuosina 1939–1944. Musiikkielämän tarjonta, haasteet ja merkitys poikkeusoloissa. Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Musiikkitiede Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma Lokakuu 2020 117 + Liitteet Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tässä tutkimuksessa kartoitetaan elävä taidemusiikin konserttitoiminta Helsingissä sotavuosina 1939–1944 eli talvisodan, välirauhan ja jatkosodan ajalta. Tällaista kattavaa musiikkikentän kartoitusta tuolta ajalta ei ole aiemmin tehty. Olennainen tutkimuskysymys on sota-ajan aiheuttamien haasteiden kartoitus. Tutkimalla sotavuosien musiikkielämän ohjelmistopolitiikkaa ja vastaanottoa haetaan vastauksia siihen, miten sota-aika on heijastunut konserteissa ja niiden ohjelmistoissa ja miten merkitykselliseksi yleisö on elävän musiikkielämän kokenut. Tutkimuksen viitekehys on historiallinen. Aineisto on kerätty arkistotutkimuksen menetelmin ja useita eri lähteitä vertailemalla on pyritty mahdollisimman kattavaan kokonaisuuteen. Tutkittava -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 57,1937-1938, Subscription Series

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth i4g2 FIFTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1937-1938 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1937, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. The OFFICERS and TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Bentley W. Warren President Henry B. Sawyer Vice-President Ernest B. Dane Treasurer Allston Burr M. A. De Wolfe Howe Henry B. Cabot Roger I. Lee Ernest B. Dane Richard C. Paine Alvan T. Fuller Henry B. Sawyer N. Penrose Hallowell Edward A. Taft Bentley W. Warren G. E. Judd, Manager C. W. Spalding, Assistant Manager [*9S] . Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON The principal business of this company is: 1 Investment of funds and management of property for living persons. 2. Carrying out the provisions of the last will and testament of deceased persons. Our officers would welcome a chance to dis- cuss with you either form of service. <lAHied with The First National Bank of Boston [!94] : SYMPHONIANA Albert Roussel TAILORED Jacques Fevrier and Ravel's Concerto Mozart and Strauss to the Queen's taste Exhibition of Etchings The "Romeo and Juliet" Records ALBERT ROUSSEL April 5, 1869-August 23, 1937 L'ART D'ALBERT ROUSSEL VIVRA TOUJOURS. SA MUSIQUE EST UNE PAGE INEFFACABLE DANS LE LIVRE DOR DE L'ART MUSICAL FRANCAIS. SON GENIE CREATEUR GARDE "L'ELAN VITAL" INVISIBLE, PULSATIF ET SCINTILLANT DE LA PERFEC- TION ORGANIQUE. LA MORT D'ALBERT ROUSSEL LAISSE UN VIDE IRREMEDIABLE DANS LE MONDE MUSICAL, AINSI QUE DANS LA VIE PRIVEE DE TOUS CEUX QUI L'ONT CONNU. -

THURSDAY SERIES 7 John Storgårds, Conductor Golda

2.3. THURSDAY SERIES 7 Helsinki Music Centre at 19.00 John Storgårds, conductor Golda Schultz, soprano Ernest Pingoud: La face d’une grande ville 25 min 1. La rue oubliée 2. Fabriques 3. Monuments et fontaines 4. Reclames lumineuses 5. Le cortege des chomeurs 6. Vakande hus 7. Dialog der Strassenlaternen mit der Morgenröte W. A. Mozart: Concert aria “Misera, dove son” 7 min W. A. Mozart: Concert aria “Vado, ma dove” 4 min W. A. Mozart: Aria “Non più di fiori” 9 min from the opera La clemenza di Tito INTERVAL 20 min John Adams: City Noir, fpF 30 min I The City and its Double II The Song is for You III Boulevard Nighto Interval at about 20.00. The concert ends at about 21.00. 1 ERNEST PINGOUD rare in Finnish orchestral music, as was the saxophone that enters the scene a (1887–1942): LA FACE moment later. The short, quick Neon D’UNE GRANDE VILLE Signs likewise represents new technol- ogy: their lights flicker in a xylophone, The works of Ernest Pingoud fall into and galloping trumpets assault the lis- three main periods. The young com- tener’s ears. The dejected Procession of poser was a Late-Romantic in the spirit the Unemployed makes the suite a true of Richard Strauss, but in the 1910s he picture of the times; the Western world turned toward a more animated brand was, after all, in the grips of the great of Modernism inspired by Scriabin and depression. Houses Waking provides a Schönberg. In the mid-1920s – as it glimpse of the more degenerate side happened around the time the days of urban life, since the houses are of of the concert focusing on a particular course brothels in which life swings composer began to be numbered – he to the beat of a fairly slow dance-hall entered a more tranquil late period and waltz. -

Olli Kortekangas' Opera Premiere Sven-David Sandström at 75

NORDIC HIGHLIGHTS 3/2017 NEWSLETTER FROM GEHRMANS MUSIKFÖRLAG & FENNICA GEHRMAN Olli Kortekangas’ opera premiere Sven-David Sandström at 75 NEWS Angela Hewitt Edicson Ruiz’s 25th to premiere Whittall performance Angela Hewitt is to be the soloist on 5 It will be his 25th perfor- October in the world premiere in Ottawa, mance, when Edicson Canada, of the piano concerto Nameless Ruiz gives the German Seas by Matthew Whittall. Conducting premiere of Rolf Mar- the National Arts Centre Orchestra will tinsson’s Double Bass Con- be Hannu Lintu. The performance is certo with the Deutsche part of the ‘Ideas of North’ festival cel- Radiophilharmonie Saa- ebrating Canada’s 150th and Finland’s rbrücken Kaiserslauten 100th birthdays. The Lapland Chamber in June of next year. The Orchestra will also be part of the pro- Australian premiere took gramme, with Kalevi Aho’s 14th sym- place last April with the phony Rituals . Queensland Symphony The Whittall concerto was commis- Orchestra, and Novem- sioned jointly by PianoEspoo Festival and ber will see the Chi- the National Arts Centre Corporation. nese premiere with the The Finnish premiere is scheduled on Hong Kong Sinfonietta. OLIVEROS NOHELY PHOTO: 10 November by the Finnish Radio Ruiz has performed the concerto earlier with orchestras in Symphony Orchestra with Risto-Matti Venezuela, Japan, Taiwan, Sweden, Spain, Austria, France and PHOTO: PETER SEARLE PETER PHOTO: Marin as the soloist. Hungary. Tango solo on stage Colourstrings in Apple iBook Store Soprano Marika Krook and a chamber ensemble Colourstrings goes digital! The Violin and Cello ABC books are from Stockholm are to perform the monologue now available as digital publications in the Apple iBook Store. -

The Queen Among Instruments

Dossier | The Queen among instruments The Queen among instruments The Organ in the Goldener Saal Since 2011, the famous organ façade, which dominates the Großer Musivereinssaal, has hidden one of the best concert organs in the world. The instrument is in fact the fourth to occupy the space since the Musikverein building opened in 1870 and provides a tangible link to this institution’s fascinating organ history. It is undoubtedly the central element in Theophil Hansen’s visually and acoustically brilliant Großer Musikvereinssaal: the organ, queen of the instruments, the focus for concert audiences in the hall and also – at least every 1 January – for millions of television viewers around the world. Hansen ensured this majestic instrument was prominently located at the front of the auditorium. The organ clearly and consistently forms an integral part of the homogenous and opulent design modelled upon Greek antiquity. And yet what we see in visual presentation here is “only” the husk, the casing. The organ itself, the instrument as such, is hidden inside and even the visible facade pipes are, and have always been, silent. Husk and heart When the Großer Musikvereinssaal opened for the first time at a celebratory event in January 1870, the organ case was still empty. In the course of the ambitious building project, at immense financial outlay, to build its new concert building, the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna had initially given less priority to the organ project. However, since the 1868 study plan created for the Gesellschaft’s own conservatory envisaged organ playing as an important component of musical education, the plans for an organ began immediately thereafter. -

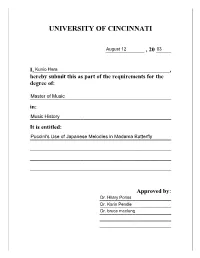

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

VÄINÖ RAITIO: ANTIGONE OP. 23 (1921–1922) Esimerkki Suomalaisesta 1920-Luvun Musiikin Modernis- Mista

VÄINÖ RAITIO: ANTIGONE OP. 23 (1921–1922) Esimerkki suomalaisesta 1920-luvun musiikin modernis- mista Hanna Isolammi Pro gradu -tutkielma Helsingin yliopisto Taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Musiikkitiede Marraskuu 2007 1 SISÄLLYS: 1 JOHDANTO 2 SUOMALAINEN MUSIIKIN MODERNISMI 1920-LUVULLA 2.1 Modernismi-termin merkitys suomalaisessa taiteessa 2.2 Musiikillinen modernismi ja sen vastaanotto Suomessa 2.2.1 Modernismin puolestapuhujia 2.2.2 Musiikkikritiikissä käytetystä terminologiasta 2.3 Modernismi 1920-luvun suomalaisessa orkesterimusiikissa 2.3.1 Ernest Pingoud 2.3.2 Elmer Diktonius 2.3.3 Aarre Merikanto 3 VÄINÖ RAITIO 3.1 Raition elämästä 3.2 Raition säveltäjäkuvasta ja tyylillisistä esikuvista 3.3 Raition 1920-luvun orkesteriteokset 4 ANTIGONE OP. 23, SYNTYHISTORIA JA RESEPTIO 4.1 Kantaesitys vuonna 1922 4.2 Säveltaiteilijain Liiton vuosikonsertti vuonna 1948 4.3 Lahden kaupunginorkesterin konsertti vuonna 2001 ja Radion Sinfoniaorkes- terin konsertti vuonna 2007 4.4 Ondinen Raition 1920-luvun teoksia sisältävä levy vuonna 1992 4.5 Muita arvioita 5 ANTIGONE OP. 23, ANALYYSI 5.1 Tematiikka 5.1.1 Antigonen kuolinuhri veljelleen 5.1.2 Tyrannin tuomio 5.1.3 Antigonen kuolema 5.2 Muoto 5.2.1 Antigonen kuolinuhri veljelleen 5.2.2 Tyrannin tuomio 5.2.3 Antigonen kuolema 5.3 Soitinnus 5.3.1 Puupuhaltimet 5.3.2 Vaskipuhaltimet 5.3.3 Lyömäsoittimet 5.3.4 Harput ja celesta 5.3.5 Jousisoittimet 5.4 Harmonia 6 JOHTOPÄÄTÖKSET LÄHTEET LIITTEET 2 1 JOHDANTO Väinö Raitio (1891–1945) on yksi kolmesta 1900-luvun alkupuolella vaikuttaneesta suomalaisesta modernistisäveltäjästä Ernest Pingoud’n ja Aarre Merikannon ohella. Raition tuotanto koostuu orkesteriteoksista, oopperoista sekä pienimuotoisemmista piano- ja laulusävellyksistä. -

Acceptance of Western Piano Music in Japan and the Career of Takahiro Sonoda

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE ACCEPTANCE OF WESTERN PIANO MUSIC IN JAPAN AND THE CAREER OF TAKAHIRO SONODA A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By MARI IIDA Norman, Oklahoma 2009 © Copyright by MARI IIDA 2009 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My document has benefitted considerably from the expertise and assistance of many individuals in Japan. I am grateful for this opportunity to thank Mrs. Haruko Sonoda for requesting that I write on Takahiro Sonoda and for generously providing me with historical and invaluable information on Sonoda from the time of the document’s inception. I must acknowledge my gratitude to following musicians and professors, who willingly told of their memories of Mr. Takahiro Sonoda, including pianists Atsuko Jinzai, Ikuko Endo, Yukiko Higami, Rika Miyatani, Y ōsuke Niin ō, Violinist Teiko Maehashi, Conductor Heiichiro Ōyama, Professors Jun Ozawa (Bunkyo Gakuin University), Sh ūji Tanaka (Kobe Women’s College). I would like to express my gratitude to Teruhisa Murakami (Chief Concert Engineer of Yamaha), Takashi Sakurai (Recording Engineer, Tone Meister), Fumiko Kond ō (Editor, Shunju-sha) and Atsushi Ōnuki (Kajimoto Music Management), who offered their expertise to facilitate my understanding of the world of piano concerts, recordings, and publications. Thanks are also due to Mineko Ejiri, Masako Ōhashi for supplying precious details on Sonoda’s teaching. A special debt of gratitude is owed to Naoko Kato in Tokyo for her friendship, encouragement, and constant aid from the beginning of my student life in Oklahoma. I must express my deepest thanks to Dr. -

Orfeo De Monteverdi

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XXII - Nº 216 - Febrero 2007 - 6,50 € ENCUENTROS Ennio Morricone DOSIER 400 años de Orfeo de Monteverdi DISCOS Ganadores Cannes Classical Awards ACTUALIDAD Año XXII - Nº 216 Febrero 2007 Vadim Repin Benet Casablancas JAZZ Nostalgia de Chet Baker AÑO XXII - Nº 216 - Febrero 2007 - 6,50 € 2 OPINIÓN DOSIER CON NOMBRE Orfeo de Monteverdi 113 PROPIO Estilo estructura y significado 8 Vadim Repin Andrea Bombi 114 Ella, la música Joaquín Martín de Sagarmínaga Pedro Elías 118 10 Benet Casablancas Lamento por Alessandro Francisco Ramos Striggio Santiago Martín Bermúdez 122 12 AGENDA Discografía Alfredo Brotons Muñoz 126 18 ACTUALIDAD NACIONAL ENCUENTROS Ennio Morricone 38 ACTUALIDAD Franco Soda 132 INTERNACIONAL EDUCACIÓN 44 ENTREVISTA Pedro Sarmiento 138 Claudio Cavina JAZZ Ana Mateo Pablo Sanz 140 48 Discos del mes LIBROS 142 SCHERZO DISCOS LA GUÍA 146 49 Sumario CONTRAPUNTO Norman Lebrecht 152 Colaboran en este número: Javier Alfaya, Daniel Álvarez Vázquez, Julio Andrade Malde, Íñigo Arbiza, Emili Blasco, Andrea Bombi, Alfredo Brotons Muñoz, José Antonio Cantón, Mikel Cañada, Jacobo Cortines, Rafael Díaz Gómez, Patrick Dillon, Pedro Elías Mamou, José Luis Fernández, Fernando Fraga, José Antonio García y García, Juan García-Rico, Antonio Gascó, Mario Gerteis, José Guerrero Martín, Fernando Herrero, Bernd Hoppe, Antonio Lasierra, Norman Lebrecht, Juan Antonio Llorente, Fiona Maddocks, Bernardo Mariano, Santiago Martín Bermúdez, Joaquín Martín de Sagarmínaga, Enrique Martínez Miura, Aurelio Martínez Seco, Blas Matamoro, Ana Mateo, Miguel Morate, Juan Carlos Moreno, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Rafael Ortega Basagoiti, Josep Pascual, Enrique Pérez Adrián, Paolo Petazzi, Francisco Ramos, Arturo Reverter, Jaime Rodríguez Pombo, Leopoldo Rojas-O’Donnell, Stefano Russomanno, Pablo Sanz, Pedro Sarmiento, Bruno Serrou, Franco Soda, José Luis Téllez, Claire Vaquero Williams, Asier Vallejo Ugarte, Pablo J. -

TOCC0419DIGIBKLT.Pdf

PIANO, ORGAN, HARMONIUM: THREE INSTRUMENTS, THREE SONORITIES, ONE TECHNIQUE by Annikka Konttori-Gustafsson and Jan Lehtola Te works recorded on this album are rather rare, having been composed or transcribed for the unusual combination of piano and harmonium. Why should a composer opt to bring two very diferent keyboard instruments together as a duo? Te answer can be found by taking a closer look at the co-existence of piano, organ and harmonium. Te technique required to play each of them did not difer enormously in the Romantic era, and in the nineteenth century in particular students were taught to play the organ in the same way as they were the piano. Te reason may lie in the fact that many of the major composers of organ music of the time, such as Brahms, Franck, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Saint-Saëns and Schumann, were also frst-class pianists. Te piano infuenced not only organists’ technique but organ-building as a whole. Te works of these pianist- composers posed new challenges in the organ lof, and various aids were devised to make playing organs as efortless as playing the piano: the organ keys, for example, were enlarged until they soon resembled those of the piano. Te Romantic era also fostered interest in the harmonium; it was an inexpensive instrument and added variety to music-making in the home. Easy to carry about and capable of producing a range of timbres, it also enjoyed a career as a concert instrument that, though brief, was rich in repertoire. Many important composers wrote for it, among them Berlioz, Boëllmann, Dvořák, Franck, Karg-Elert, Vierne and Widor. -

The 20Th Century Through Historiographies and Textbooks Chapters from Japan, East Asia, Slovenia and Southeast Europe

21 THE 20TH CENTURY THROUGH HISTORIOGRAPHIES AND TEXTBOOKS CHAPTERS FROM JAPAN, EAST ASIA, SLOVENIA AND SOUTHEAST EUROPE THE 20TH CENTURY THROUGH HISTORIOGRAPHIES AND TEXTBOOKS CHAPTERS FROM JAPAN, EAST ASIA, SLOVENIA AND SOUTHEAST EUROPE EDITORS ŽARKO LAZAREVIĆ NOBUHIRO SHIBA KENTA SUZUKI Ljubljana 2018 The 20th Century Through Historiographies and Textbooks ZALOŽBA INZ Odgovorni urednik dr. Aleš Gabrič ZBIRKA VPOGLEDI 21 ISSN 2350-5656 Žarko Lazarević, Nobuhiro Shiba, Kenta Suzuki (eds.) THE 20TH CENTURY THROUGH HISTORIOGRAPHIES AND TEXTBOOKS CHAPTERS FROM JAPAN, EAST ASIA, SLOVENIA AND SOUTHEAST EUROPE Recenzenta dr. Danijela Trškan dr. Shigemori Bučar Chikako Jezikovni pregled Eva Žigon Oblikovanje Barbara Bogataj Kokalj Založnik Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino Tisk Medium d.o.o. Naklada 300 izvodov Izid knjige je podprla Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike Slovenije CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 94(100)"19"(082) The 20th century through historiographies and textbooks : chapters from Japan, East Asia, Slovenia and Southeast Europe / editors Žarko Lazarević, Nobuhiro Shiba, Kenta Suzuki. - Ljubljana : INZ, 2018. - (Zbirka Vpogledi ; 21, ISSN 2350-5656) ISBN 978-961-6386-89-0 1. Lazarević, Žarko 297387008 © 2018, Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, hired out, transmitted, published, adapted or used in any other way, including photocopying, printing, recording or storing and publishing in the electronic form without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-com- mercial uses permitted by copyright law. Culiberg: Some Thoughts on School, Education, History and Ideology CONTENTS Nobuhiro Shiba – Žarko Lazarević: Preface ...............................................................