A History of Hampshire, Including the Isle of Wight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week Ending 12Th February 2010

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 06 Week Ending: 12th February 2010 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 10/00166/FULLN Erection of two replacement 33 And 34 Andover Road, Red Mr & Mrs S Brown Jnr Mrs Lucy Miranda YES 08.02.2010 dwellings together with Post Bridge, Andover, And Mr R Brown Page ABBOTTS ANN garaging and replacement Hampshire SP11 8BU 12.03.2010 and resiting of entrance gates 10/00248/VARN Variation of condition 21 of 11 Elder Crescent, Andover, Mr David Harman Miss Sarah Barter 10.02.2010 TVN.06928 - To allow garage Hampshire, SP10 3XY 05.03.2010 ABBOTTS ANN to be used for storage room -

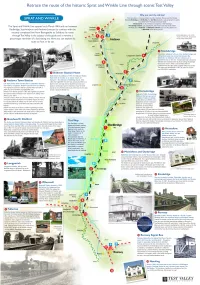

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

Parish Churches of the Test Valley

to know. to has everything you need you everything has The Test Valley Visitor Guide Visitor Valley Test The 01264 324320 01264 Office Tourist Andover residents alike. residents Tourist Office 01794 512987 512987 01794 Office Tourist Romsey of the Borough’s greatest assets for visitors and and visitors for assets greatest Borough’s the of villages and surrounding countryside, these are one one are these countryside, surrounding and villages ensure visitors are made welcome to any of them. of any to welcome made are visitors ensure of churches, and other historic buildings. Together with the attractive attractive the with Together buildings. historic other and churches, of date list of ALL churches and can offer contact telephone numbers, to to numbers, telephone contact offer can and churches ALL of list date with Bryan Beggs, to share the uniqueness of our beautiful collection collection beautiful our of uniqueness the share to Beggs, Bryan with be locked. The Tourist Offices in Romsey and Andover hold an up to to up an hold Andover and Romsey in Offices Tourist The locked. be This leaflet has been put together by Test Valley Borough Council Council Borough Valley Test by together put been has leaflet This church description. Where an is shown, this indicates the church may may church the indicates this shown, is an Where description. church L wide range of information to help you enjoy your stay in Test Valley. Valley. Test in stay your enjoy you help to information of range wide every day. Where restrictions apply, an is indicated at the end of the the of end the at indicated is an apply, restrictions Where day. -

Hampshire and the Company of White Paper Makers

HAMPSHIRE AND THE COMPANY OF WHITE PAPER MAKERS By J. H. THOMAS, B.A. HAMPSHIRE has long been associated with the manufacturing of writing materials, parchment being made at Andover, in the north of the county, as early as the 13th century.1 Not until some four centuries later, however, did Hampshire embark upon the making of paper, with Sir Thomas Neale (1565-1620/1) financing the construction of the one-vat mill at Warnford, in the Meon Valley, about the year 1618. As far as natural requirements were concerned, Hampshire was well-endowed for the making of paper. Clear, swift chalk-based streams ensured a steady supply of water, for use both as motive power and in the actual process of production. Rags, old ropes and sails provided the raw materials for conversion into paper, while labour was to be found in the predominantly rural population. The amount of capital required varied depend ing on the size of the mill concerned, and whether it was a conversion of existing plant, as happened at Bramshott during the years 1640-90, or whether the mill was an entirely new construction as was the case at Warnford and, so far as is known, the case with Frog Mill at nearby Curdridge. Nevertheless Hampshire, like other paper-making counties, was subject to certain restraining factors. A very harsh winter, freezing the water supply, would lead to a cut-back in production. A shortage of materials and the occurrence of Holy days would have a similar result, so that in 1700 contemporaries reckoned on an average working year of roughly 200 days.2 Serious outbreaks of plague would also hamper production, the paper-makers of Suffolk falling on hard times for this reason in 1638.3 Though Hampshire had only one paper mill in 1620, she possessed a total of ten by 1700,4 and with one exception all were engaged in the making of brown paper. -

The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1980 The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period Kristin MacLeod Tomlin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Tomlin, Kristin MacLeod, "The Influence of the Introduction of Heavy Ordnance on the Development of the English Navy in the Early Tudor Period" (1980). Master's Theses. 1921. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1921 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF THE INTRODUCTION OF HEAVY ORDNANCE ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ENGLISH NAVY IN THE EARLY TUDOR PERIOD by K ristin MacLeod Tomlin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1980 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis grew out of a paper prepared for a seminar at the University of Warwick in 1976-77. Since then, many persons have been invaluable in helping me to complete the work. I would like to express my thanks specifically to the personnel of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England, and of the Public Records Office, London, for their help in locating sources. -

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

The English Historical Review

THE ENGLISH HISTORICAL REVIEW NO. CVIIL—OCTOBER 1912 The Tribal Hidage Downloaded from HE ancient territorial list which Maitland named the T ' Tribal Hidage ' is known in two slightly differing forms, which may for convenience be designated the ' English ' and the ' Latin ', from the circumstance that one form is in English http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ throughout while the other has been partially translated into Latin. The only ' English ' text now known was discovered by Dr. Birch in the Harleian MS. 3271, fo. 0 b, and printed by him in full,1 but the names and figures had been published by Spelnian in 1626 in his Glossarium (s.v. Hide), from what he calls a veterrima scheda (perhaps a loose leaf or gathering) in the possession of Francis Tatum.2 The volume in which Dr. Birch found it is occupied mainly with grammatical treatises, but some miscel- by guest on August 11, 2015 laneous pieces are entered, in several hands, all of much the same period. The ' Tribal Hidage ' fills up what had been a blank page near the beginning.3 In the same or a like writing at the end of the book are chronological notes, ending with the state- ment that it was 6,132 years from the Creation; that Easter would fall on 2 April; that it was a leap year and the fifteenth indiction. These conditions are satisfied by the year 1032. In the ' Hidage ' the numbers are written out at length ; the whole has been corrected by another and perhaps somewhat later hand. Thus hund has been added in Herefinna (twelf hund hyda) and in the final total (twa hund thusend), and some words have been corrected ;4 while to Fcerpinga has been added the marginal note—' Is in Middel Englu Faerpinga'. -

Landowner Deposits Register

Register of Landowner Deposits under Highways Act 1980 and Commons Act 2006 The first part of this register contains entries for all CA16 combined deposits received since 1st October 2013, and these all have scanned copies of the deposits attached. The second part of the register lists entries for deposits made before 1st October 2013, all made under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980. There are a large number of these, and the only details given here currently are the name of the land, the parish and the date of the deposit. We will be adding fuller details and scanned documents to these entries over time. List of deposits made - last update 12 January 2017 CA16 Combined Deposits Deposit Reference: 44 - Land at Froyle (The Mrs Bootle-Wilbrahams Will Trust) Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/countryside/Deposit44-Bootle-WilbrahamsTrustLand-Froyle-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Crispin Mahony of Savills on behalf of The Parish: Froyle Mrs Bootle-WilbrahamWill Trust, c/o Savills (UK) Froyle Jewry Chambers,44 Jewry Street, Winchester Alton Hampshire Hampshire SO23 8RW GU34 4DD Date of Statement: 14/11/2016 Grid Reference: 733.416 Deposit Reference: 98 - Tower Hill, Dummer Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/rightsofway/Deposit98-LandatTowerHill-Dummer-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Jamie Adams & Madeline Hutton Parish: Dummer 65 Elm Bank Gardens, Up Street Barnes, Dummer London Basingstoke SW13 0NX RG25 2AL Date of Statement: 27/08/2014 Grid Reference: 583. 458 Deposit Reference: -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Paris to Hayling Reunion Bike Ride

Hayling Cycle Ride Practice Ride From The Ship Langstone to The Shoe, Exton and back From The Ship turn right. Just before roundabout turn left into Langstone Technology Park. Turn right into the car park and go to the end and take the footpath on the right-hand side. Join footpath and go left, towards Portsmouth. At end turn right into Brookside Road. Zero mileage here 0.1 At roundabout turn right into Brockhampton Road 0.2 Straight over roundabout 0.5 At T junction (Prince of Wales Pub) turn left into Bedhampton Road. Go over Bedhampton level crossing to join main road. Straight over at traffic lights 1.1 At roundabout take 2nd exit onto Portsdown Hill Road. Up and over motorway and straight on; go past The George and The Churchillian 5.4 Turn Right into Pigeon House Lane (before the Southwick roundabout) WARNING – Fast descent with loose gravel Take Care crossing The Ford – you can dismount and use the bridge 6.2 Bear Left after The Ford 8.1 Turn Left – sign Denmead 2 8.4 Turn Left – sign Denmead 8.9 At T Junction go Straight On (cycle path only) Mead End Road 9.1 Straight On into Mill Road 9.3 Turn Right on Anmore Road – sign Clanfield 5 10.8 Bear Left – sign Hinton Daubney 11.5 Turn Left down Old Mill Lane – sign Denmead Mill 12.0 Turn Right on Old Mill Lane – sign Bat and Ball 13.7 Turn Left at the crossroads in front of the Bat and Ball pub 13.9 Turn 1st Right (just after the trees) – sign Chidden 15.1 Bear Left at the end of the descent – sign Hambledon Follow road to Meonstoke and Droxford 16.8 Turn Right – sign East Meon and Coombe 16.9 Straight on at Crossroads – sign Corhampton 18.6 Bear Left onto Shavards Lane – sign South Downs Way 18.9 At A32 junction go straight across into Beacon Hill Lane – WARNING this is a busy road 19.0 The Shoe is our lunch stop for today. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

Coarse Fishing Close Season on English Rivers

Coarse fishing close season on English rivers Appendix 1 – Current coarse fish close season arrangements The close season on different waters In England, there is a coarse fish close season on all rivers, some canals and some stillwaters. This has not always been the case. In the 1990s, only around 60% of the canal network had a close season and in some regions, the close season had been dispensed with on all stillwaters. Stillwaters In 1995, following consultation, government confirmed a national byelaw which retained the coarse fish close season on rivers, streams, drains and canals, but dispensed with it on most stillwaters. The rationale was twofold: • Most stillwaters are discrete waterbodies in single ownership. Fishery owners can apply bespoke angling restrictions to protect their stocks, including non-statutory close times. • The close season had been dispensed with on many stillwaters prior to 1995 without apparent detriment to those fisheries. This presented strong evidence in favour of removing it. The close season is retained on some Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) and the Norfolk and Suffolk Broads, as a precaution against possible damage to sensitive wildlife - see Appendix 1. This consultation is not seeking views on whether the close season should be retained on these stillwaters While most stillwater fishery managers have not re-imposed their own close season rules, some have, either adopting the same dates as apply to rivers or tailoring them to their waters' specific needs. Canals The Environment Agency commissioned a research project in 1997 to examine the evidence around the close season on canals to identify whether or not angling during the close season was detrimental to canal fisheries.