Open PDF 226KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament Elections 2014 RESEARCH PAPER 14/32 11 June 2014

European Parliament Elections 2014 RESEARCH PAPER 14/32 11 June 2014 Elections to the European Parliament were held across the 28 states of the European Union between 22 and 25 May 2014. The UK elections were held concurrently with council elections in England and Northern Ireland on 22 May. The UK now has 73 MEPs, up from 72 at the last election, distributed between 12 regions. UKIP won 24 seats, Labour 20, the Conservatives 19, and the Green Party three. The Liberal Democrats won only one seat, down from 11 at the 2009 European election. The BNP lost both of the two seats they had won for the first time at the previous election. UKIP won the popular vote overall, and in six of the nine regions in England. Labour won the popular vote in Wales and the SNP won in Scotland. Across the UK as a whole turnout was 35%. Across Europe there was an increase in the number of seats held by Eurosceptic parties, although more centrist parties in established pro-European groups were still in the majority. The exact political balance of the new Parliament depends on the formation of the political groups. Turnout across the EU was 43%. It was relatively low in some of the newer Member States. Part 1 of this paper presents the full results of the UK elections, including regional analysis and local-level data. Part 2 presents a summary of the results across the EU, together with country-level summaries based on data from official national sources. Oliver Hawkins Vaughne Miller Recent Research Papers 14/22 Accident & Emergency Performance: England 2013/14. -

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

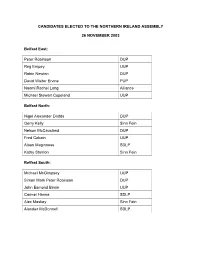

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from -

Parlement Européen

19.9.2014 FR Journal officiel de l'Union européenne C 326 / 1 IV (Informations) INFORMATIONS PROVENANT DES INSTITUTIONS, ORGANES ET ORGANISMES DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE PARLEMENT EUROPÉEN QUESTIONS ÉCRITES AVEC RÉPONSE Questions écrites par les membres du Parlement européen avec les réponses données par l'institution européenne concernée (2014/C 326/01) Sommaire Page E-002772/14 by Diane Dodds to the Commission Subject: Intervention in Uganda English version ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 15 E-002773/14 by Diane Dodds to the Commission Subject: Cost of living in European cities English version ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 16 E-002774/14 by Diane Dodds to the Commission Subject: Islamic militant groups in Syria English version ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 17 E-002775/14 by Diane Dodds to the Commission Subject: Brain tumour research English version ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 18 E-002776/14 by Diane Dodds to the Commission -

The European Elections and Brexit Foreword

The European Elections and Brexit Foreword There is a certain irony that the upcoming set of European elections will be the most scrutinized, most keenly watched and most thoroughly dissected ever in the UK. It remains far from certain any of those elected will ever make the journey on the Eurostar from St Pancras to Brussels as members of the European Parliament. However, these elections are undoubtedly significant: for the EU as a whole, and for Brexit and the future of British politics. This report represents our attempt to explain why and to spell out for those interested what to look out for when the elections take place. In what follows, we bring together some of the best minds working on Brexit and the EU. The report is intended as a guide to the vote later this month, rather than an attempt to predict the outcome of an inherently unpredictable set of elections. I believe it makes an original and timely contribution and I hope you find it both useful and interesting. It was an absolute pleasure to work with Sara Hobolt in putting this report together. Special thanks to the ever patient, creative, understanding and brilliant Richard Linnett. Matt Bevington, Liam Hill, Alan Wager and John-Paul Salter all proofed and checked the various contributions. Navjyot Lehl who coordinated the whole enterprise with her customary efficiency and (sometimes) good humour. Professor Anand Menon Director, The UK in a Changing Europe Hyperlinks to cited material can be found online at www.UKandEU.ac.uk 2 May 2019 The UK in a Changing Europe promotes rigorous, high-quality and independent research into the complex and ever changing relationship between the UK and the EU. -

European Election Manifesto 2019 Delivering for Everyone in Northern Ireland European Manifesto 2019

European Election Manifesto 2019 Delivering for Everyone in Northern Ireland European Manifesto 2019 Contents RT HON ARLENE FOSTER MLA 5 DIANE DODDS MEP 7 LEAVING THE EUROPEAN UNION 9 AN EXPERIENCED REPRESENTATIVE 10 - Delivering Across Northern Ireland 11 - Representing the people of Northern Ireland 11 in the European Parliament - A Record of Delivery For Agriculture 12 - For Innocent Victims Of Terrorism 13 - Protecting The Most Vulnerable 14 - For Tackling Cyber-Bullying And Online Exploitation 14 - For Connecting Local Businesses 15 - For Citizens Travelling Across The EU 15 - For Older People 15 WORKING ON THE POLICIES THAT MATTER TO YOU 16 - Agriculture 18 - Food Supply Chain 19 - The Backstop Threat 20 - Environment 20 - Rural Communities 21 - Fisheries – Righting The Wrong 22 - Sharing The Prosperity Of The United Kingdom 24 - A New Approach 24 - Future Peace And INTERREG Funds 25 - Participation In Other EU Funds 26 - Security 26 - A Fair Share Of Brexit Dividends 27 - Increased Local Powers 27 - Immigration And Skills 28 - A Fair Settlement On Citizens Rights 28 - Cyber-Crime And Internet Safety 29 - European Court of Justice 29 - Innocent Victims 30 - Religious Persecution 31 - An EU Army 31 2 3 Delivering for Everyone in Northern Ireland European Manifesto 2019 Rt Hon Arlene Foster MLA Party Leader On 23rd June 2016, the people of the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. It was the largest vote in the history of our country. Whatever the variations in the referendum result, from town to town, constituency by constituency, or region to region, it was a national question and we reached a national decision. -

Women in Power A-Z of Female Members of the European Parliament

Women in Power A-Z of Female Members of the European Parliament A Alfano, Sonia Andersdotter, Amelia Anderson, Martina Andreasen, Marta Andrés Barea, Josefa Andrikiené, Laima Liucija Angelilli, Roberta Antonescu, Elena Oana Auconie, Sophie Auken, Margrete Ayala Sender, Inés Ayuso, Pilar B Badía i Cutchet, Maria Balzani, Francesca Băsescu, Elena Bastos, Regina Bauer, Edit Bearder, Catherine Benarab-Attou, Malika Bélier, Sandrine Berès, Pervenche Berra, Nora Bilbao Barandica, Izaskun Bizzotto, Mara Blinkevičiūtė, Vilija Borsellino, Rita Bowles, Sharon Bozkurt, Emine Brantner, Franziska Katharina Brepoels, Frieda Brzobohatá, Zuzana C Carvalho, Maria da Graça Castex, Françoise Češková, Andrea Childers, Nessa Cliveti, Minodora Collin-Langen, Birgit Comi, Lara Corazza Bildt, Anna Maria Correa Zamora, Maria Auxiliadora Costello, Emer Cornelissen, Marije Costa, Silvia Creţu, Corina Cronberg, Tarja D Dăncilă, Vasilica Viorica Dati, Rachida De Brún, Bairbre De Keyser, Véronique De Lange, Esther Del Castillo Vera, Pilar Delli, Karima Delvaux, Anne De Sarnez, Marielle De Veyrac, Christine Dodds, Diane Durant, Isabelle E Ernst, Cornelia Essayah, Sari Estaràs Ferragut, Rosa Estrela, Edite Evans, Jill F Fajon, Tanja Ferreira, Elisa Figueiredo, Ilda Flašíková Beňová, Monika Flautre, Hélène Ford, Vicky Foster, Jacqueline Fraga Estévez, Carmen G Gabriel, Mariya Gál, Kinga Gáll-Pelcz, Ildikó Gallo, Marielle García-Hierro Caraballo, Dolores García Pérez, Iratxe Gardiazábal Rubial, Eider Gardini, Elisabetta Gebhardt, Evelyne Geringer de Oedenberg, Lidia Joanna -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

Committee for Infrastructure OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Northern Ireland Hydrogen Ambitions: Wrightbus and Ryse Hydrogen 11 November 2020 NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY Committee for Infrastructure Northern Ireland Hydrogen Ambitions: Wrightbus and Ryse Hydrogen 11 November 2020 Members present for all or part of the proceedings: Miss Michelle McIlveen (Chairperson) Mr David Hilditch (Deputy Chairperson) Ms Martina Anderson Mr Roy Beggs Mr Cathal Boylan Mr Keith Buchanan Mrs Dolores Kelly Ms Liz Kimmins Mr Andrew Muir Witnesses: Mr Buta Atwal Wrightbus and Ryse Hydrogen Mr Jo Bamford Wrightbus and Ryse Hydrogen The Chairperson (Miss McIlveen): A briefing paper can be found in members' packs. Hansard will report the session. The witnesses from Wrightbus and Ryse Hydrogen are attending via StarLeaf. We welcome Mr Jo Bamford, the chairman, and Mr Buta Atwal, the chief executive. Gentlemen, you are very welcome to the Committee. We had hoped to visit Wrightbus. That has not been possible due to the pandemic, but, hopefully, it will happen in the near future. If you would like to make your presentation, members will then follow up with some questions. Mr Jo Bamford (Wrightbus and Ryse Hydrogen): Good morning. Thank you very much for welcoming us to your Committee today. I have probably met some of you along the way over the last year. It has been an interesting year at Wrightbus. Buta Atwal, who is with us today, has been fighting battles and fires and has had an interesting year. What is happening at Wrightbus? [Inaudible] bankruptcy last June. When we took over the business, there were 45 people left in the business. -

HSENI Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 2019-20

ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 1 April 2019 - 31 March 2020 Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland CONTROLLING RISK TOGETHER Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland Annual Report and Accounts For the year ended 31 March 2020 Laid before the Northern Ireland Assembly under paragraph 19 (3) of Schedule 2 of the Health and Safety at Work (Northern Ireland) Order 1978 by the Department for the Economy OGL 23 October 2020 © Crown copyright 2015 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v.2. To view this licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/2/ or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information, you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is also available at http://www.hseni.gov.uk Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland, 83 Ladas Drive, Belfast, BT6 9FR, Northern Ireland; Email: [email protected] Annual Report 2019–2020 3 Key Facts and Figures for 2019 - 2020 Key trends in work-related injuries are as • dealt with 1,110 complaints about alleged follows: unsatisfactory working conditions and activities; • fatalities within areas under the responsibility of HSENI down by 2 to 11 (P)1 , compared • prepared three sets of Northern Ireland to 13 2 in the previous year; Statutory Rules, initiated one consultation and developed two Agency Agreements; • fatalities in the agriculture sector reduced significantly from seven to one fatality in this • submitted an Annual Equality Report to the sector in 2019-20; Equality Commission; • fatalities in the construction sector increased • organised four key events. -

Official Report (Hansard)

Official Report (Hansard) Monday 11 June 2012 Volume 75, No 5 Session 2011-2012 Contents Assembly Business ....................................................................................................................249 Executive Committee Business Pensions Bill: Royal Assent .........................................................................................................249 Assembly Business Resignation: Ms Martina Anderson ..............................................................................................249 Extension of Sitting ....................................................................................................................249 Ministerial Statement Pathways to Success: Strategy for Young People not in Education, Employment or Training ..............250 Executive Committee Business Financial Services Bill: Legislative Consent Motion .......................................................................258 Goods Vehicles (Licensing of Operators) (Exemption) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2012 ...............264 Social Security Benefits Up-rating Order (Northern Ireland) 2012 ...................................................269 Committee Business Economy: Innovation, Research and Development .........................................................................270 Oral Answers to Questions Agriculture and Rural Development ..............................................................................................276 Education ..................................................................................................................................282 -

Ranking European Parliamentarians on Climate Action

Ranking European Parliamentarians on Climate Action EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CONTENTS With the European elections approaching, CAN The scores were based on the votes of all MEPs on Austria 2 Europe wanted to provide people with some these ten issues. For each vote, MEPs were either Belgium 3 background information on how Members of the given a point for voting positively (i.e. either ‘for’ Bulgaria 4 European Parliament (MEPs) and political parties or ‘against’, depending on if the text furthered or Cyprus 5 represented in the European Parliament – both hindered the development of climate and energy Czech Republic 6 national and Europe-wide – have supported or re- policies) or no points for any of the other voting Denmark 7 jected climate and energy policy development in behaviours (i.e. ‘against’, ‘abstain’, ‘absent’, ‘didn’t Estonia 8 the last five years. With this information in hand, vote’). Overall scores were assigned to each MEP Finland 9 European citizens now have the opportunity to act by averaging out their points. The same was done France 10 on their desire for increased climate action in the for the European Parliament’s political groups and Germany 12 upcoming election by voting for MEPs who sup- all national political parties represented at the Greece 14 ported stronger climate policies and are running European Parliament, based on the points of their Hungary 15 for re-election or by casting their votes for the respective MEPs. Finally, scores were grouped into Ireland 16 most supportive parties. CAN Europe’s European four bands that we named for ease of use: very Italy 17 Parliament scorecards provide a ranking of both good (75-100%), good (50-74%), bad (25-49%) Latvia 19 political parties and individual MEPs based on ten and very bad (0-24%). -

The Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol Responding to Tensions Or Enacting Opportunity?

The Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol Responding to Tensions or Enacting Opportunity? Professor Peter Shirlow FAcSS Michael D’Arcy Alison Grundle Jarlath Kearney Professor Brendan Murtagh Contents 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 11 3. Framing the Debate .................................................................................................................... 16 3.1 Movement of Goods ............................................................................................................... 17 3.2 East-West Trade: Impacts ....................................................................................................... 18 3.3 North-South Trade and Business ........................................................................................... 23 3.4 Societal and Political Tensions ............................................................................................... 25 4. Tensions Resolved: Rights and the N/S Dimension .............................................................. 43 4.1 Article 2: Rights of individuals .............................................................................................. 44 4.2 New Powers, Functions, Resources, and the ‘Dedicated Mechanism’ ............................. 45 5. Mapping the Future .................................................................................................................. -

Minutes of the Proceedings of the Meeting of the Council Held at Mossley Mill on Monday 26 October 2020 at 6.30 Pm

MINUTES OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE MEETING OF THE COUNCIL HELD AT MOSSLEY MILL ON MONDAY 26 OCTOBER 2020 AT 6.30 PM In the Chair : Mayor (Councillor J Montgomery) Members Present : Aldermen – F Agnew, P Brett, T Burns, T Campbell, L Clarke, M Girvan, J McGrath, P Michael and J Smyth Councillors – J Archibald, A Bennington, M Cooper, H Cushinan, P Dunlop, G Finlay, S Flanagan, R Foster, J Gilmour M Goodman, P Hamill, L Irwin, N Kelly, R Kinnear, A M Logue, R Lynch, N McClelland, T McGrann, V McWilliam, M Magill, N Ramsay, V Robinson, S Ross, L Smyth, M Stewart, R Swann, B Webb and R Wilson Officers Present : Chief Executive - J Dixon Director of Economic Development and Planning – M McAlister Director of Operations – G Girvan Director of Finance and Governance – S Cole Director of Community Planning – N Harkness Director of Organisation Development – A McCooke Borough Lawyer and Head of Legal Services – P Casey ICT Change Officer – A Cole ICT Projects Officer – J Higginson Member Services Manager – V Lisk In Attendance : Mr Colm McQuillan, Director of Housing Services, NIHE Mr Frank O’Connor, Regional Manager for North Division, NIHE Ms Breige Mullaghan, Area Manager South, NIHE Ms Alice McAteer, Place Shaper South, NIHE In order to protect public health during the current COVID-19 emergency it was not possible to allow the public or the press to physically attend the meeting. The public and the press could access those parts of the meeting which they are entitled to attend via live stream (a link to which is on the Council website).