Children First: the Child Protection System in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Monitoring Written Parliamentary Questions

House of Commons Procedure Committee Monitoring written Parliamentary questions Seventh Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes and oral evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 17 April 2013 HC 1095 Published on 8 May 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £11.00 Procedure Committee The Procedure Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider the practice and procedure of the House in the conduct of public business, and to make recommendations. Current membership Mr Charles Walker MP (Conservative, Broxbourne) (Chair) Jenny Chapman MP (Labour, Darlington) Nic Dakin MP (Labour, Scunthorpe) Thomas Docherty MP (Labour, Dunfermline and West Fife) Sir Roger Gale MP (Conservative, North Thanet) Helen Goodman MP (Labour, Bishop Auckland) Mr James Gray MP (Conservative, North Wiltshire) Tom Greatrex MP (Lab/Co-op, Rutherglen and Hamilton West) John Hemming MP (Liberal Democrat, Birmingham Yardley) Mr David Nuttall MP (Conservative, Bury North) Jacob Rees-Mogg MP (Conservative, North East Somerset) Martin Vickers MP (Conservative, Cleethorpes) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the Parliament: Rt Hon Greg Knight MP (Conservative, Yorkshire East) (Chair until 6 September 2012) Karen Bradley MP (Conservative, Staffordshire Moorlands) Andrew Percy MP (Conservative, Brigg and Goole) Bridget Phillipson MP (Labour, Houghton and Sunderland South) Angela Smith MP (Labour, Penistone and Stocksbridge) Sir Peter Soulsby MP (Labour, Leicester South) Mike Wood MP (Labour, Batley and Spen) Powers The powers of the Committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 147. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. -

New Zealand - Bilateral Visit to Auckland & Wellington Report Summary 9 -14 April 2018

NEW ZEALAND - BILATERAL VISIT TO AUCKLAND & WELLINGTON REPORT SUMMARY 9 -14 APRIL 2018 PROGRAMME OVERVIEW A bilateral programme saw a UK in terms of preserving the delegation comprised of four Members natural landscape for future of the House of Commons and two generations, and to ensure Members of the House of Lords engage that the unique agricultural with parliamentary colleagues, business, conditions are maintained. and civil society to discuss issues and • Parliamentary practice, challenges relevant to the UK and particularly with a focus New Zealand. Key topics of discussion on proxy voting, newly included: implemented in New Zealand IMPACT & OUTCOMES and the focus of discussion in • The state of international the UK. Impact. relations, particularly the • Trade relationships between To build knowledge and understanding current geopolitical relations the two countries, and the of shared national and regional issues between Russia and the UK and different forms a post-Brexit through exchanges with parliamentary its allies. trade relationship might take. colleagues, and further develop the good • The above discussions were relationship between the UK Parliament made more pertinent by The bilateral element of the delegation and the Parliament of New Zealand. developments in the Syrian was followed by the Pacific Islands conflict that unfolded during Parliamentary Workshop which Outcomes. the visit. provided an opportunity to engage with parliamentarians from ten Pacific Island Through a programme of meetings, • Domestic policy, including a focus on immigration, both in countries on areas of mutual interest. briefings, plenary sessions and interactive the UK and in NZ. This has been covered in a separate discussions, the programme will deliver • Environmental concerns, both report. -

Questions Tabled on Fri 13 Jul 2018

Published: Monday 16 July 2018 Questions tabled on Friday 13 July 2018 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Monday 16 July Questions for Written Answer 1 Nic Dakin (Scunthorpe): To ask the Attorney General, with reference to tables three and seven of the Crown Prosecution Service Annual Report 2016-17, what the reasons are for conviction rates in Magistrates Courts being higher than those in Crown Court; and what assessment his Department has made of the reasons for defendants having a 25 per cent greater chance of acquittal at a Crown Court than at a Magistrates Court. [Transferred] (163550) 2 Tom Brake (Carshalton and Wallington): To ask the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, what discussions have taken place in negotiations on the UK leaving the EU on UK citizens and businesses paying mobile roaming charges in the EU after the UK has left the EU; and if he will make a statement. [Transferred] (163492) 3 Tom Brake (Carshalton and Wallington): To ask the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, what discussions the Government has had with the European Commission on ensuring that businesses can hold and transfer data and personal information to EU member states without interruption after the UK has left the EU. -

NEC Annual Report 2019

Labour Party | Annual Report 2019 LABOUR PARTY ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Treasurers’ Responsibilities . 54 Foreword from Jeremy Corbyn . 5 Independent Auditor’s Report Introduction from Tom Watson . 7 to the members of the Labour Party . 55 Introduction from the General Secretary . 9 Consolidated income and expenditure account 2018/2019 National Executive Committee . 10 for the year ended 31 December 2018 . 57 NEC Committees . 12 Statements of comprehensive income Obituaries . 13 and changes in equity for the year ended NEC aims and objectives for 2019 . 14 31 December 2018 . 58 Consolidated balance sheet BY-ELECTIONS . 15 at 31 December 2018 . 59 Peterborough . 16 Consolidated cash flow statement for the year Newport West . 17 ended 31 December 2018 . 60 ELECTIONS 2019 . 19 Notes to Financial Statements . 61 Analysis . 20 APPENDICES . 75 Local Government Report . 23 Members of Shadow Cabinet LOOKING AHEAD: 2020 ELECTIONS . 25 and Opposition Frontbench . 76 The year ahead in Scotland . 26 Parliamentary Labour Party . 80 The year ahead in Wales . 27 Members of the Scottish Parliament. 87 NEC PRIORITIES FOR 2019 . 29 Members of the Welsh Assembly . 88 Members and Supporters Members of the European Parliament . 89 Renewing our party and building an active Directly Elected Mayors . 90 membership and supporters network . 30 Members of the London Assembly . 91 Equalities . 31 Leaders of Labour Groups . 92 Labour Peers . 100 NEC PRIORITIES FOR 2019 . 35 Labour Police and Crime Commissioners . 103 National Policy Forum Parliamentary Candidates endorsed NPF Report . 36 by the NEC at time of publication . 104 NEC PRIORITIES FOR 2019 . 39 NEC Disputes . 107 International NCC Cases . -

Hyenas of the Limpopo

Hyenas of the Limpopo Hyenas of the Limpopo The Social Politics of Undocumented Movement across South Africa’s Border with Zimbabwe Xolani Tshabalala Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 729 Faculty of Arts and Sciences Linköping 2017 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science • No. 729 At the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Linköping University, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad problem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. This thesis comes from Institute for Research on Migration, Ethnicity and Society (REMESO) at the Department of Social and Welfare Studies. Distributed by: Department of Social and Welfare Studies Linköping University 581 83 Linköping Xolani Tshabalala Hyenas of the Limpopo: The Social Politics of Undocumented Movement across South Africa’s Border with Zimbabwe Edition 1:1 ISBN 978-91-7685-408-2 ISSN 0282-9800 © Xolani Tshabalala Department of Social and Welfare Studies 2017 Typesetting and cover by Merima Mešić Printed by: LiU-Tryck, Linköping 2017 Acknowledgements The decision to pursue PhD level studies at what in the beginning seemed like a faraway place represented a leap into the unknown. Along the winding journey that has brought me to this point, I have accumulated many debts. I will never be able to recall or pay them all, and in explicitly acknowledging the help of some people here, I remain equally indebted, in the spirit of the gift, to many others whose generosity is all the more appreciated in its namelessness. -

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report General Committees

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT GENERAL COMMITTEES Public Bill Committee HIGH SPEED RAIL (PREPARATION) BILL Fifth Sitting Tuesday 16 July 2013 (Morning) CONTENTS CLAUSE 1 under consideration when the Committee adjourned till this day at Two o’clock. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE LIMITED £6·00 PBC (Bill 010) 2013 - 2014 Members who wish to have copies of the Official Report of Proceedings in General Committees sent to them are requested to give notice to that effect at the Vote Office. No proofs can be supplied. Corrigenda slips may be published with Bound Volume editions. Corrigenda that Members suggest should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Saturday 20 July 2013 STRICT ADHERENCE TO THIS ARRANGEMENT WILL GREATLY FACILITATE THE PROMPT PUBLICATION OF THE BOUND VOLUMES OF PROCEEDINGS IN GENERAL COMMITTEES © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2013 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 159 Public Bill Committee16 JULY 2013 High Speed Rail (Preparation) Bill 160 The Committee consisted of the following Members: Chairs: †ANNETTE BROOKE,JIM SHERIDAN † Burns, Mr Simon (Minister of State, Department † Morrice, Graeme (Livingston) (Lab) for Transport) † Reid, Mr Alan (Argyll and Bute) (LD) † Dakin, Nic (Scunthorpe) (Lab) † Shannon, Jim (Strangford) (DUP) † Dobson, -

One Nation Fizz

ONE NATION power hope community Edited by Owen Smith & Rachel Reeves London 2013 Edited by Roberta Blackman-Woods, Diana Johnson, Barbara Keeley1 One Nation Fizz © the authors 2014 ISBN 978-1-910448-00-7 This ebook is published in 2014 by Fizz publications All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Acknowledgements We wish to acknowledge the support of Jon Cruddas, Jonathan Rutherford and his team for their endless patience as parliamentary business, constituency concerns and the odd election (!!) got in the way of our progress. We also appreciate the encouragement of Ed Miliband for spurring us on to get thinking about policy development and committing our ideas to paper. All problems and inconsistencies etc are of course our own. Cover design Fran Davies, www.daviesbatt.co.uk Typesetting e-type Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Roberta Blackman-Woods, Diana Johnson and Barbara Keeley 5 1. Andrew Gwynne A One Nation Health Service fit for the twenty-first century 14 2. Barbara Keeley Whole person care and a new covenant with carers 22 3. Sharon Hodgson Involving communities to support child development 31 4. Kevin Brennan Education as an equaliser 41 5. Paul Blomfield and Nic Dakin Energising Further and Higher Education to boost our nation’s future 51 6. Gordon Marsden Transforming skills and life chances for 2020 Britain 61 7. -

Written Evidence Submitted by 4Children

Written evidence submitted by 4Children Introduction 1. 4Children is the national charity all about children and families. We have spearheaded a joined-up, integrated approach to children’s services and work with a wide range of partners around the country to ensure children and families have access to the services and support they need in their communities. We run Sure Start Children’s Centres as well as family and youth services across Britain. 2. We develop, influence and shape national policy on all aspects of the lives of children, young people and families. As the Government’s lead strategic partner for early years and childcare we have a crucial role in co-producing policy with the Department of Education and representing the sector’s views and experiences. Our national campaigns, like Give Me Strength, change policy and practice and put the needs of children and families on the political and policy agenda. 3. Our family outreach workers work with parents in their own homes, providing help, advice and practical help and our specialist teams work to support vulnerable families experiencing drug or alcohol addiction, domestic violence and post-natal depression. 4. 4Children welcomes the opportunity to contribute to this important inquiry. There is no more important issue that how we can ensure the children and young people in the United Kingdom are kept safe from harm, neglect and abuse. 5. 4Children is concerned that the current debate about child protection is too polarised around the issue of whether or not children are taken into care expeditiously enough. Vitally important as this issue is, the risk is that it skews focus and resources away from the much larger group of children suffering from harm, neglect or whose life chances are being seriously compromised. -

(Scunthorpe and Brigg & Goole) Results

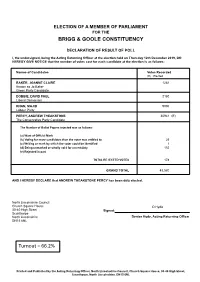

ELECTION OF A MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE BRIGG & GOOLE CONSTITUENCY DECLARATION OF RESULT OF POLL I, the undersigned, being the Acting Returning Officer at the election held on Thursday 12th December 2019, DO HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the number of votes cast for each candidate at the election is as follows: Names of Candidates Votes Recorded (E) : Elected BAKER, JOANNE CLAIRE 1281 Known as Jo Baker Green Party Candidate DOBBIE, DAVID PAUL 2180 Liberal Democrats KHAN, MAJID 9000 Labour Party PERCY, ANDREW THEAKSTONE 30941 (E) The Conservative Party Candidate The Number of Ballot Papers rejected was as follows: (a) Want of Official Mark (b) Voting for more candidates than the voter was entitled to 25 (c) Writing or mark by which the voter could be identified 1 (d) Being unmarked or wholly void for uncertainty 152 (e) Rejected in part TOTAL REJECTED VOTES 178 GRAND TOTAL 43,580 AND I HEREBY DECLARE that ANDREW THEAKSTONE PERCY has been duly elected. North Lincolnshire Council Church Square House D Hyde 30-40 High Street Signed: Scunthorpe North Lincolnshire Denise Hyde, Acting Returning Officer DN15 6NL Turnout = 66.2% Printed and Published by the Acting Returning Officer, North Lincolnshire Council, Church Square House, 30-40 High Street, Scunthorpe, North Lincolnshire, DN15 6NL ELECTION OF A MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE SCUNTHORPE CONSTITUENCY DECLARATION OF RESULT OF POLL I, the undersigned, being the Acting Returning Officer at the election held on Thursday 12th December 2019, DO HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that the number of votes cast for -

New MP Briefing: Health the Vuelio Political Team Have Put Together a Briefing on First Time Mps with a Background in Health. Da

New MP briefing: Health The Vuelio political team have put together a briefing on first time MPs with a background in health. Dave Doogan Dave Doogan MP is a member of the Scottish National Party, representing the constituency of Angus since 12th December 2019, where he achieved a majority of 3,795 votes. In his professional career Doogan was an Aircraft Engineer within the Ministry of Defence. He left the Civil Service to study at Dundee University in 2007 and drove taxis during this period, graduating with a First-Class Honours Degree in 2011. Doogan also has experiences as a self- employed landscaping contractor. In his political career he was elected as an SNP Councillor in 2012 and was appointed to leadership roles within: Health/Social Care and Housing , leader of the opposition at Perth and Kinross Council, and as leader of the local SNP group. He was re-elected in 2017. He has since stepped down as Councillor following his election success. During his election campaign Doogan has also campaigned strongly against Brexit. Outside of work, he enjoys spending his time with his wife and two children. Ian Levy Ian Levy is the Conservative MP for Blyth Valley. He won the seat of Blyth Valley for the Conservatives on the 12th December 2019. This was the first time in 84 years that Blyth Valley has had a Conservative MP. He beat his Labour opponent by 17,440 votes to 16,728 handing him a majority of 712. The traditional Labour stronghold was held by veteran MP Ronnie Campbell, but he was replaced at this election by Susan Dungworth.