Light Pollution, Sleep Deprivation, and Infant Health at Birth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light Pollution by Stephen Davis − 2/26/08

1 Prepared for SAB's review of EPA "Report on the Environment (2007)" [minor changes 3/11/08] Light Pollution by Stephen Davis − 2/26/08 One thing the EPA has been pushing is its "Green Lights" program. Using energy efficient light bulbs is not good enough: a) When too much light is being used, b) When aimed improperly, or c) When nobody is there to use it.[1] This is "Light Pollution!" And there is way too much of it costing the USA some $4.5 billion or more annually. This energy and money could be put to far better use. [2,3] Light Pollution and all its ramifications are missing from the EPA "Report on the Environment."[4,5] The #1 and #2 problems in Congress, needing immediate attention, are the economy and climate change. Both are directly related to energy independence and homeland security.[6] There is a connection between Light Pollution and what Congress considers as in our best interests. Unfortunately, government hasn't been watching were the money goes and how it is spent. We need accountability[7,8] and awareness[9] at all levels right down to the common man on the street before it's too late and we are all looking for life boats. What happened to "conservation" − the word that is never to be spoken?[10,] What if the money and other resources aren't there, or could they be put to better use elsewhere? The federal government can lead the way and get others involved through policy, guidance, and monitoring. -

Reducing Light Pollution in a Tourism-Based Economy, with Recommendations for a National Lighting Ordinance

REDUCING LIGHT POLLUTION IN A TOURISM-BASED ECONOMY, WITH RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A NATIONAL LIGHTING ORDINANCE Prepared by the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) Kimberley N. Lake and Karen L. Eckert __________________________________________________________ WIDECAST Technical Report No. 11 2009 Cover photos: Tree-mounted double spotlights at the Frangipani Beach Resort, with new hotel construction in the background (photo by Kimberley Lake); Leatherback sea turtle hatchling attracted by beachfront lighting and unable to find the sea (photo by Sebastien Barrioz). For bibliographic purposes, this publication should be cited as follows: Lake, Kimberley N. and Karen L. Eckert. 2009. Reducing Light Pollution in a Tourism-Based Economy, with Recommendations for a National Lighting Ordinance. Prepared by the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) for the Department of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Government of Anguilla. WIDECAST Technical Report No. 11. Ballwin, Missouri. 65 pp. ISSN: 1930-3025 Copies of the publication may be obtained from: Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) 1348 Rusticview Drive Ballwin, Missouri 63011 Phone: + (314) 954-8571 Email: [email protected] Online at www.widecast.org REDUCING LIGHT POLLUTION IN A TOURISM-BASED ECONOMY, WITH RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A NATIONAL LIGHTING ORDINANCE Kimberley N. Lake Karen L. Eckert 2009 Lake and Eckert (2009) ~ Reducing Light Pollution in a Tourism-Based Economy ~ WIDECAST Technical Report 11 PREFACE AND INTENT For more than two decades, the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST, www.widecast.org), with Country Coordinators in more than 40 Caribbean nations and territories, has linked scientists, conservationists, natural resource users and managers, policy-makers, industry groups, educators, and other stakeholders together in a collective effort to develop a unified management framework, and to promote a region-wide capacity to design and implement science-based sea turtle conservation programs. -

Measuring Night Sky Brightness: Methods and Challenges

Measuring night sky brightness: methods and challenges Andreas H¨anel1, Thomas Posch2, Salvador J. Ribas3,4, Martin Aub´e5, Dan Duriscoe6, Andreas Jechow7,13, Zolt´anKollath8, Dorien E. Lolkema9, Chadwick Moore6, Norbert Schmidt10, Henk Spoelstra11, G¨unther Wuchterl12, and Christopher C. M. Kyba13,7 1Planetarium Osnabr¨uck,Klaus-Strick-Weg 10, D-49082 Osnabr¨uck,Germany 2Universit¨atWien, Institut f¨urAstrophysik, T¨urkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Wien, Austria tel: +43 1 4277 53800, e-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) 3Parc Astron`omicMontsec, Comarcal de la Noguera, Pg. Angel Guimer`a28-30, 25600 Balaguer, Lleida, Spain 4Institut de Ci`encies del Cosmos (ICCUB), Universitat de Barcelona, C.Mart´ıi Franqu´es 1, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 5D´epartement de physique, C´egep de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Qu´ebec, J1E 4K1, Canada 6Formerly with US National Park Service, Natural Sounds & Night Skies Division, 1201 Oakridge Dr, Suite 100, Fort Collins, CO 80525, USA 7Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, 12587 Berlin, Germany 8E¨otv¨osLor´andUniversity, Savaria Department of Physics, K´arolyi G´asp´ar t´er4, 9700 Szombathely, Hungary 9National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, 3720 Bilthoven, The Netherlands 10DDQ Apps, Webservices, Project Management, Maastricht, The Netherlands 11LightPollutionMonitoring.Net, Urb. Ve¨ınatVerneda 101 (Bustia 49), 17244 Cass`ade la Selva, Girona, Spain 12Kuffner-Sternwarte,Johann-Staud-Straße 10, A-1160 Wien, Austria 13Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany Abstract Measuring the brightness of the night sky has become an increasingly impor- tant topic in recent years, as artificial lights and their scattering by the Earth’s atmosphere continue spreading around the globe. -

Heavy Metals Contents and Risk Assessment of Farmland on the Edge of Sichuan Basin

ISSN: 2572-4061 Yang et al. J Toxicol Risk Assess 2019, 5:018 DOI: 10.23937/2572-4061.1510018 Volume 5 | Issue 1 Journal of Open Access Toxicology and Risk Assessment RESEARCH ARTICLE Heavy metals contents and risk assessment of farmland on the edge of Sichuan Basin Mengling Yang2,3, Dan Zhang2*, Lu Xu2,4, Shamshad Khan2, Fan Chen1 and Hao Jiang2 1Tobacco Company of Liangshan, China 2Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China Check for updates 3Bossco Environmental Protection Group, China 4University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, China *Corresponding author: Dan Zhang, Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 9, Section 4, Renmin South Road, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China Sichuan is a major agricultural province in China, Abstract with second large arable flied area in China. Agricultural This study features a survey of the concentrations of heavy metals (Cu, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb, Mn, Co, Se) in surface soils products quality is closely related to the purity of soil. (0-30 cm), carried out in edge of Sichuan Basin (Pingdi, It’s necessary to measure and evaluate the soil heavy Puan, Xingwen, Gulin). The contamination of heavy metals metals pollution in order to guarantee the sustainability in soil was assessed with single-factor pollution index of agricultural products’ quality and safety. Since the method and Nemerow comprehensive pollution index 1980s, researchers have began to focus on the heavy method. The results showed that Cu, Cr, Ni, Pb, Co were main risk factors of soil heavy metal pollution. In Gulin, the metals pollution in Chendu Plain, but few report on the concentrations of Cd, Mn and Se were higher than other risk assessment of farmland heavy metals contents on three areas, with the sample over-standard rate of 90, the edge of Sichuan [9-12]. -

Health and Safety Code Chapter 425. Regulation of Certain Outdoor Lighting

HEALTH AND SAFETY CODE TITLE 5. SANITATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY SUBTITLE F. LIGHT POLLUTION CHAPTER 425. REGULATION OF CERTAIN OUTDOOR LIGHTING Sec.A425.001.AADEFINITIONS. In this chapter: (1)AA"Cutoff luminaire" means a luminaire in which 2.5% or less of the lamp lumens are emitted above a horizontal plane through the luminaire 's lowest part and 10% or less of the lamp lumens are emitted at a vertical angle 80 degrees above the luminaire 's lowest point. (2)AA"Light pollution" means the night sky glow caused by the scattering of artificial light in the atmosphere. (3)AA"Outdoor lighting fixture" means any type of fixed or movable lighting equipment that is designed or used for illumination outdoors. The term includes billboard lighting, street lights, searchlights and other lighting used for advertising purposes, and area lighting. The term does not include lighting equipment that is required by law to be installed on motor vehicles or lighting required for the safe operation of aircraft. (4)AA"State funds" means: (A)AAmoney appropriated by the legislature; or (B)AAbond revenues of the state. Added by Acts 1999, 76th Leg., ch. 713, Sec. 1, eff. Sept. 1, 1999. Renumbered from Sec. 421.001 by Acts 2001, 77th Leg., ch. 1420, Sec. 21.001(76), eff. Sept. 1, 2001. Sec.A425.002.AASTANDARDS FOR STATE-FUNDED OUTDOOR LIGHTING FIXTURES. (a) An outdoor lighting fixture may be installed, replaced, maintained, or operated using state funds only if: (1)AAthe new or replacement outdoor lighting fixture is a cutoff luminaire if the rated output -

Students' Opinions on the Light Pollution Application

International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 2015, 8(1), 55-68 Students’ Opinions on the Light Pollution Application Cengiz ÖZYÜREK Ordu University, Turkey Güliz AYDIN Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Turkey Received: June, 2015 / Revised: August, 2015 / Accepted: August, 2015 Abstract The purpose of this study is to determine the impact of computer-animated concept cartoons and outdoor science activities on creating awareness among seventh graders about light pollution. It also aims to identify the views of the students on the activities that were carried out. This study used one group pre-test/post-test experimental design model with 30 seventh graders. The data in the study were collected via open-ended questions on light pollution and semi-structured interview questions. The open-ended questions on light pollution were administered as a pre-test and a post- test. After the post-test was administered, semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven students. The data collected from the open-ended questions and semi-structured interviews were qualitatively analysed and quotes from the students’ statements were included. Looking at the answers of the students to questions on light pollution, it was understood that the activities that were carried out were effective. Furthermore, all of the students that were interviewed made positive statements about the activities that were carried out. Keywords: Light pollution, Concept cartoons, Students’ views. Introduction Humans are an indispensable part of the environment that they live in. Due to the rapid increase in population, overurbanization, industrialization and, consequently, the excessive use of natural resources, today, environmental issues have become global issues. -

The Impact of Light Pollution on Eutrophication Of

610 Tomasz Ściężor, Wojciech Balcerzak ściężor T., Kubala M., KaszoWsKi W., DWoraK T. z., Wioś 2014. Ocena wód wykorzystywanych do za- 2010. Zanieczyszczenie świetlne nocnego nieba opatrzenia ludności w wodę przeznaczoną do w obszarze aglomeracji krakowskiej. Analiza spożycia w województwie małopolskim w 2013 pomiarów sztucznej poświaty niebieskiej. Wy- roku. WIOŚ Kraków. dawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej, Kraków. WalKer M. F., 1988. The effect of solar activity on the V and B band sky brightness. Publ. Astro- nom. Soc. Pacific 100, 496–505. ToMasz ściężor, Wojciech balcerzaK Wydział Inżynierii Środowiska Politechnika Krakowska Warszawska 24, 31-155 Kraków WPŁYW ZANIECZYSZCZENIA ŚWIETLNEGO NA EUTROFIZACJĘ ZBIORNIKA DOBCZYCKIEGO Streszczenie W literaturze przedmiotu od dawna opisywany jest wpływ światła Księżyca na pionowe migracje zooplanktonu w zbiornikach wodnych. Biorąc pod uwagę oczywisty fakt, że pożywieniem zooplanktonu jest fitoplankton, postawiono hi- potezę o możliwej korelacji między jasnością nocnego nieba a zawartością fitoplanktonu w warstwach powierzchniowych zbiornika wodnego. W celu weryfikacji tej hipotezy wykonano całoroczne pomiary jasności nocnego nieba w rejonie uję- cia wody na Zbiorniku Dobczyckim. Stwierdzono wyraźną liniową korelację między poziomem chlorofilu a w warstwach powierzchniowych tego zbiornika a jasnością nocnego nieba. Nie stwierdzono jakichkolwiek podobnych korelacji między poziomem chlorofilu a a innymi wskaźnikami jakości wody, takimi jak temperatura czy natlenienie, jak również z parame- trami meteorologicznymi, takimi jak temperatura powietrza czy nasłonecznienie w ciągu dnia. Postawiono tezę, że jasność nocnego nieba, na którą składają się zarówno czynniki naturalne (światło Księżyca), jak sztuczne (zanieczyszczenie świetl- ne w postaci sztucznej poświaty niebieskiej), jest głównym i decydującym czynnikiem wpływającym na rozwój glonów w warstwie powierzchniowej Zbiornika Dobczyckiego. Postawiono tezę, że poprawne oświetlenie okolic ujęć wody może znacząco obniżyć eutrofizację zbiorników wodnych. -

Snowglow—The Amplification of Skyglow by Snow and Clouds Can

Journal of Imaging Article Snowglow—The Amplification of Skyglow by Snow and Clouds Can Exceed Full Moon Illuminance in Suburban Areas Andreas Jechow 1,2,* and Franz Hölker 1,3 1 Ecohydrology, Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, 12587 Berlin, Germany 2 Remote Sensing, GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 3 Institute of Biology, Freie Universität Berlin, 14195 Berlin, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Artificial skyglow, the fraction of artificial light at night that is emitted upwards from Earth and subsequently scattered back within the atmosphere, depends on atmospheric conditions but also on the ground albedo. One effect that has not gained much attention so far is the amplification of skyglow by snow, particularly in combination with clouds. Snow, however, has a very high albedo and can become important when the direct upward emission is reduced when using shielded luminaires. In this work, first results of skyglow amplification by fresh snow and clouds measured with all-sky photometry in a suburban area are presented. Amplification factors for the zenith luminance of 188 for snow and clouds in combination and 33 for snow alone were found at this site. The maximum zenith luminance of nearly 250 mcd/m2 measured with snow and clouds is a factor of 1000 higher than the commonly used clear sky reference of 0.25 mcd/m2. Compared with our darkest zenith luminance of 0.07 mcd/m2 measured for overcast conditions in a very remote area, this leads to an overall amplification factor of ca. -

View a Copy of This Licence, Visit

Zhang et al. Environmental Health (2020) 19:74 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-00628-4 RESEARCH Open Access A large prospective investigation of outdoor light at night and obesity in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study Dong Zhang1* , Rena R. Jones2, Tiffany M. Powell-Wiley3, Peng Jia4,5, Peter James6 and Qian Xiao7 Abstract Background: Research has suggested that artificial light at night (LAN) may disrupt circadian rhythms, sleep, and contribute to the development of obesity. However, almost all previous studies are cross-sectional, thus, there is a need for prospective investigations of the association between LAN and obesity risk. The goal of our current study was to examine the association between baseline LAN and the development of obesity over follow-up in a large cohort of American adults. Methods: The study included a sample of 239,781 men and women (aged 50–71) from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study who were not obese at baseline (1995–1996). We used multiple logistic regression to examine whether LAN at baseline was associated with the odds of developing obesity at follow-up (2004–2006). Outdoor LAN exposure was estimated from satellite imagery and obesity was measured based on self-reported weight and height. Results: We found that higher outdoor LAN at baseline was associated with higher odds of developing obesity over 10 years. Compared with the lowest quintile of LAN, the highest quintile was associated with 12% and 19% higher odds of developing obesity at follow-up in men (OR (95% CI) = 1.12 (1.00, 1.250)) and women (1.19 (1.04, 1.36)), respectively. -

A Model to Determine Naked-Eye Limiting Magnitude

Volume 10 Issue 1 (2021) HS Research A Model to Determine Naked-Eye Limiting Magnitude Dasha Crocker1, Vincent Schmidt1 and Laura Schmidt1 1Bellbrook High School, Bellbrook, OH, USA ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to determine which variables would be needed to generate a model that predicted the naked eye limiting magnitude on a given night. After background research was conducted, it seemed most likely that wind speed, air quality, skyglow, and cloud cover would contribute to the proposed model. This hypothesis was tested by obtaining local weather data, then determining the naked eye limiting magnitude for the local conditions. This procedure was repeated for the moon cycle of October, then repeated an additional 11 times in November, December, and January. After the initial 30 trials, r values were calculated for each variable that was measured. These values revealed that wind was not at all correlated with the naked eye limiting magnitude, but pollen (a measure of air quality), skyglow, and cloud cover were. After the generation of several models using multiple regression tests, air quality also proved not to affect the naked eye limiting magnitude. It was concluded that skyglow and cloud cover would contribute to a model that predicts naked eye limiting magnitude, proving the original hypothesis to be partially correct. Introduction Humanity has been looking to the stars for thousands of years. Ancient civilizations looked to the stars hoping that they could explain the world around them. Mayans invented shadow casting devices to track the movement of the sun, moon, and planets, while Chinese astronomers discovered Ganymede, one of Jupiter’s moons (Cook, 2018). -

Light Pollution Associated with Delayed Sleep Time: a Major Hygienic Problem in Saudi Arabia

Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science, 2017, 7, 125-136 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jbbs ISSN Online: 2160-5874 ISSN Print: 2160-5866 Light Pollution Associated with Delayed Sleep Time: A Major Hygienic Problem in Saudi Arabia Hussain Gadelkarim Ahmed1,2*, Saleh Ahmed Alogla1, Rayan Mohsen Ismael1, Abdulkarim Ali Alqufayi1, Saleh Othman Alamer1, Hamoud Khalid Alshaya1, Abdulsalam Eisa Mazyad Alshammari1 1Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, University of Hail, Hail, KSA 2Molecular Diagnostics and Personalized Therapeutics Unit, University of Hail, Hail, KSA How to cite this paper: Ahmed, H.G., Abstract Alogla, S.A., Ismael, R.M., Alqufayi, A.A., Alamer, S.O., Alshaya, H.K. and Alshamma- Background: It was well established that exposure to nighttime light was re- ri, A.E.M. (2017) Light Pollution Associated sponsible of a diverse negative health effect. Therefore, the aim of this study with Delayed Sleep Time: A Major Hygienic was to assess the epidemiologic exposure to artificial light at night time and Problem in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Beha- vioral and Brain Science, 7, 125-136. negative health consequences that associated with prolonged nighttime light- https://doi.org/10.4236/jbbs.2017.73012 ing exposure. Methodology: This is a cross-sectional survey, involving a total of 266 Saudi residents living in the city of Hail, Northern KSA. Essential in- Received: February 10, 2017 formation regarding exposure to light at night time was obtained. Results: Accepted: March 11, 2017 Published: March 14, 2017 The overall incidence of nighttime light exposure in the present study was 65.8% for general population, was 61.5% males and was 38.5% for females. -

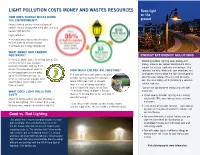

Light Pollution Costs Money and Wastes Resources

LIGHT POLLUTION COSTS MONEY AND WASTES RESOURCES Keep light on the HOW DOES ENERGY WASTE HARM THE ENVIRONMENT? ground Excess lighting pumps millions of tons of carbon into our atmosphere every year, and also causes light pollution. Light pollution: • Increases greenhouse gas emissions • Contributes to climate change • Increases our energy dependence WHAT ABOUT OUR CARBON FOOTPRINT? ENERGY EFFICIENCY SOLUTIONS In the U.S. alone, about 15 million tons of CO 2 Shielding outdoor lighting saves energy and are emitted each year to power money, reduces our carbon footprint and helps residential outdoor lighting. That protect the natural nighttime environment. The equals the emissions of about 3 HOW MUCH ENERGY AM I WASTING? solutions are easy. Work with your neighbors and million passenger cars and adds local government to keep the light on the ground up to 40,000 tons per day. To The average house with poorly designed and the skies natural. It’s a win-win for every- offset all that carbon dioxide, we’d outdoor lighting wastes 0.5 kilowatt- one. You save money while preserving a valuable need to plant about 600 million hours (kWh) per night. A kilowatt- natural resource. trees annually! hour is a unit of energy equivalent to one kilowatt of power for an hour. Tips to help you conserve energy and use light WHAT DOES LIGHT POLLUTION It’s enough energy to power a 50-inch efficiently: COST? plasma TV for one hour or run one load in • Install quality outdoor lighting to cut energy your dishwasher! About $3 billion dollars per year of energy is use by 60-70%, save money and cut carbon lost to bad lighting.