View a Copy of This Licence, Visit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light Pollution by Stephen Davis − 2/26/08

1 Prepared for SAB's review of EPA "Report on the Environment (2007)" [minor changes 3/11/08] Light Pollution by Stephen Davis − 2/26/08 One thing the EPA has been pushing is its "Green Lights" program. Using energy efficient light bulbs is not good enough: a) When too much light is being used, b) When aimed improperly, or c) When nobody is there to use it.[1] This is "Light Pollution!" And there is way too much of it costing the USA some $4.5 billion or more annually. This energy and money could be put to far better use. [2,3] Light Pollution and all its ramifications are missing from the EPA "Report on the Environment."[4,5] The #1 and #2 problems in Congress, needing immediate attention, are the economy and climate change. Both are directly related to energy independence and homeland security.[6] There is a connection between Light Pollution and what Congress considers as in our best interests. Unfortunately, government hasn't been watching were the money goes and how it is spent. We need accountability[7,8] and awareness[9] at all levels right down to the common man on the street before it's too late and we are all looking for life boats. What happened to "conservation" − the word that is never to be spoken?[10,] What if the money and other resources aren't there, or could they be put to better use elsewhere? The federal government can lead the way and get others involved through policy, guidance, and monitoring. -

Reducing Light Pollution in a Tourism-Based Economy, with Recommendations for a National Lighting Ordinance

REDUCING LIGHT POLLUTION IN A TOURISM-BASED ECONOMY, WITH RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A NATIONAL LIGHTING ORDINANCE Prepared by the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) Kimberley N. Lake and Karen L. Eckert __________________________________________________________ WIDECAST Technical Report No. 11 2009 Cover photos: Tree-mounted double spotlights at the Frangipani Beach Resort, with new hotel construction in the background (photo by Kimberley Lake); Leatherback sea turtle hatchling attracted by beachfront lighting and unable to find the sea (photo by Sebastien Barrioz). For bibliographic purposes, this publication should be cited as follows: Lake, Kimberley N. and Karen L. Eckert. 2009. Reducing Light Pollution in a Tourism-Based Economy, with Recommendations for a National Lighting Ordinance. Prepared by the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) for the Department of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Government of Anguilla. WIDECAST Technical Report No. 11. Ballwin, Missouri. 65 pp. ISSN: 1930-3025 Copies of the publication may be obtained from: Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST) 1348 Rusticview Drive Ballwin, Missouri 63011 Phone: + (314) 954-8571 Email: [email protected] Online at www.widecast.org REDUCING LIGHT POLLUTION IN A TOURISM-BASED ECONOMY, WITH RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A NATIONAL LIGHTING ORDINANCE Kimberley N. Lake Karen L. Eckert 2009 Lake and Eckert (2009) ~ Reducing Light Pollution in a Tourism-Based Economy ~ WIDECAST Technical Report 11 PREFACE AND INTENT For more than two decades, the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (WIDECAST, www.widecast.org), with Country Coordinators in more than 40 Caribbean nations and territories, has linked scientists, conservationists, natural resource users and managers, policy-makers, industry groups, educators, and other stakeholders together in a collective effort to develop a unified management framework, and to promote a region-wide capacity to design and implement science-based sea turtle conservation programs. -

Heavy Metals Contents and Risk Assessment of Farmland on the Edge of Sichuan Basin

ISSN: 2572-4061 Yang et al. J Toxicol Risk Assess 2019, 5:018 DOI: 10.23937/2572-4061.1510018 Volume 5 | Issue 1 Journal of Open Access Toxicology and Risk Assessment RESEARCH ARTICLE Heavy metals contents and risk assessment of farmland on the edge of Sichuan Basin Mengling Yang2,3, Dan Zhang2*, Lu Xu2,4, Shamshad Khan2, Fan Chen1 and Hao Jiang2 1Tobacco Company of Liangshan, China 2Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China Check for updates 3Bossco Environmental Protection Group, China 4University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, China *Corresponding author: Dan Zhang, Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 9, Section 4, Renmin South Road, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China Sichuan is a major agricultural province in China, Abstract with second large arable flied area in China. Agricultural This study features a survey of the concentrations of heavy metals (Cu, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb, Mn, Co, Se) in surface soils products quality is closely related to the purity of soil. (0-30 cm), carried out in edge of Sichuan Basin (Pingdi, It’s necessary to measure and evaluate the soil heavy Puan, Xingwen, Gulin). The contamination of heavy metals metals pollution in order to guarantee the sustainability in soil was assessed with single-factor pollution index of agricultural products’ quality and safety. Since the method and Nemerow comprehensive pollution index 1980s, researchers have began to focus on the heavy method. The results showed that Cu, Cr, Ni, Pb, Co were main risk factors of soil heavy metal pollution. In Gulin, the metals pollution in Chendu Plain, but few report on the concentrations of Cd, Mn and Se were higher than other risk assessment of farmland heavy metals contents on three areas, with the sample over-standard rate of 90, the edge of Sichuan [9-12]. -

Health and Safety Code Chapter 425. Regulation of Certain Outdoor Lighting

HEALTH AND SAFETY CODE TITLE 5. SANITATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY SUBTITLE F. LIGHT POLLUTION CHAPTER 425. REGULATION OF CERTAIN OUTDOOR LIGHTING Sec.A425.001.AADEFINITIONS. In this chapter: (1)AA"Cutoff luminaire" means a luminaire in which 2.5% or less of the lamp lumens are emitted above a horizontal plane through the luminaire 's lowest part and 10% or less of the lamp lumens are emitted at a vertical angle 80 degrees above the luminaire 's lowest point. (2)AA"Light pollution" means the night sky glow caused by the scattering of artificial light in the atmosphere. (3)AA"Outdoor lighting fixture" means any type of fixed or movable lighting equipment that is designed or used for illumination outdoors. The term includes billboard lighting, street lights, searchlights and other lighting used for advertising purposes, and area lighting. The term does not include lighting equipment that is required by law to be installed on motor vehicles or lighting required for the safe operation of aircraft. (4)AA"State funds" means: (A)AAmoney appropriated by the legislature; or (B)AAbond revenues of the state. Added by Acts 1999, 76th Leg., ch. 713, Sec. 1, eff. Sept. 1, 1999. Renumbered from Sec. 421.001 by Acts 2001, 77th Leg., ch. 1420, Sec. 21.001(76), eff. Sept. 1, 2001. Sec.A425.002.AASTANDARDS FOR STATE-FUNDED OUTDOOR LIGHTING FIXTURES. (a) An outdoor lighting fixture may be installed, replaced, maintained, or operated using state funds only if: (1)AAthe new or replacement outdoor lighting fixture is a cutoff luminaire if the rated output -

Students' Opinions on the Light Pollution Application

International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 2015, 8(1), 55-68 Students’ Opinions on the Light Pollution Application Cengiz ÖZYÜREK Ordu University, Turkey Güliz AYDIN Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Turkey Received: June, 2015 / Revised: August, 2015 / Accepted: August, 2015 Abstract The purpose of this study is to determine the impact of computer-animated concept cartoons and outdoor science activities on creating awareness among seventh graders about light pollution. It also aims to identify the views of the students on the activities that were carried out. This study used one group pre-test/post-test experimental design model with 30 seventh graders. The data in the study were collected via open-ended questions on light pollution and semi-structured interview questions. The open-ended questions on light pollution were administered as a pre-test and a post- test. After the post-test was administered, semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven students. The data collected from the open-ended questions and semi-structured interviews were qualitatively analysed and quotes from the students’ statements were included. Looking at the answers of the students to questions on light pollution, it was understood that the activities that were carried out were effective. Furthermore, all of the students that were interviewed made positive statements about the activities that were carried out. Keywords: Light pollution, Concept cartoons, Students’ views. Introduction Humans are an indispensable part of the environment that they live in. Due to the rapid increase in population, overurbanization, industrialization and, consequently, the excessive use of natural resources, today, environmental issues have become global issues. -

The Impact of Light Pollution on Eutrophication Of

610 Tomasz Ściężor, Wojciech Balcerzak ściężor T., Kubala M., KaszoWsKi W., DWoraK T. z., Wioś 2014. Ocena wód wykorzystywanych do za- 2010. Zanieczyszczenie świetlne nocnego nieba opatrzenia ludności w wodę przeznaczoną do w obszarze aglomeracji krakowskiej. Analiza spożycia w województwie małopolskim w 2013 pomiarów sztucznej poświaty niebieskiej. Wy- roku. WIOŚ Kraków. dawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej, Kraków. WalKer M. F., 1988. The effect of solar activity on the V and B band sky brightness. Publ. Astro- nom. Soc. Pacific 100, 496–505. ToMasz ściężor, Wojciech balcerzaK Wydział Inżynierii Środowiska Politechnika Krakowska Warszawska 24, 31-155 Kraków WPŁYW ZANIECZYSZCZENIA ŚWIETLNEGO NA EUTROFIZACJĘ ZBIORNIKA DOBCZYCKIEGO Streszczenie W literaturze przedmiotu od dawna opisywany jest wpływ światła Księżyca na pionowe migracje zooplanktonu w zbiornikach wodnych. Biorąc pod uwagę oczywisty fakt, że pożywieniem zooplanktonu jest fitoplankton, postawiono hi- potezę o możliwej korelacji między jasnością nocnego nieba a zawartością fitoplanktonu w warstwach powierzchniowych zbiornika wodnego. W celu weryfikacji tej hipotezy wykonano całoroczne pomiary jasności nocnego nieba w rejonie uję- cia wody na Zbiorniku Dobczyckim. Stwierdzono wyraźną liniową korelację między poziomem chlorofilu a w warstwach powierzchniowych tego zbiornika a jasnością nocnego nieba. Nie stwierdzono jakichkolwiek podobnych korelacji między poziomem chlorofilu a a innymi wskaźnikami jakości wody, takimi jak temperatura czy natlenienie, jak również z parame- trami meteorologicznymi, takimi jak temperatura powietrza czy nasłonecznienie w ciągu dnia. Postawiono tezę, że jasność nocnego nieba, na którą składają się zarówno czynniki naturalne (światło Księżyca), jak sztuczne (zanieczyszczenie świetl- ne w postaci sztucznej poświaty niebieskiej), jest głównym i decydującym czynnikiem wpływającym na rozwój glonów w warstwie powierzchniowej Zbiornika Dobczyckiego. Postawiono tezę, że poprawne oświetlenie okolic ujęć wody może znacząco obniżyć eutrofizację zbiorników wodnych. -

Light Pollution, Sleep Deprivation, and Infant Health at Birth

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11703 Light Pollution, Sleep Deprivation, and Infant Health at Birth Laura M. Argys Susan L. Averett Muzhe Yang JULY 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11703 Light Pollution, Sleep Deprivation, and Infant Health at Birth Laura M. Argys University of Colorado Denver and IZA Susan L. Averett Lafayette College and IZA Muzhe Yang Lehigh University JULY 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11703 JULY 2018 ABSTRACT Light Pollution, Sleep Deprivation, and Infant Health at Birth* This is the first study that uses a direct measure of skyglow, an important aspect of light pollution, to examine its impact on infant health at birth. -

Light Pollution Associated with Delayed Sleep Time: a Major Hygienic Problem in Saudi Arabia

Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science, 2017, 7, 125-136 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jbbs ISSN Online: 2160-5874 ISSN Print: 2160-5866 Light Pollution Associated with Delayed Sleep Time: A Major Hygienic Problem in Saudi Arabia Hussain Gadelkarim Ahmed1,2*, Saleh Ahmed Alogla1, Rayan Mohsen Ismael1, Abdulkarim Ali Alqufayi1, Saleh Othman Alamer1, Hamoud Khalid Alshaya1, Abdulsalam Eisa Mazyad Alshammari1 1Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, University of Hail, Hail, KSA 2Molecular Diagnostics and Personalized Therapeutics Unit, University of Hail, Hail, KSA How to cite this paper: Ahmed, H.G., Abstract Alogla, S.A., Ismael, R.M., Alqufayi, A.A., Alamer, S.O., Alshaya, H.K. and Alshamma- Background: It was well established that exposure to nighttime light was re- ri, A.E.M. (2017) Light Pollution Associated sponsible of a diverse negative health effect. Therefore, the aim of this study with Delayed Sleep Time: A Major Hygienic was to assess the epidemiologic exposure to artificial light at night time and Problem in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Beha- vioral and Brain Science, 7, 125-136. negative health consequences that associated with prolonged nighttime light- https://doi.org/10.4236/jbbs.2017.73012 ing exposure. Methodology: This is a cross-sectional survey, involving a total of 266 Saudi residents living in the city of Hail, Northern KSA. Essential in- Received: February 10, 2017 formation regarding exposure to light at night time was obtained. Results: Accepted: March 11, 2017 Published: March 14, 2017 The overall incidence of nighttime light exposure in the present study was 65.8% for general population, was 61.5% males and was 38.5% for females. -

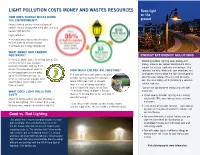

Light Pollution Costs Money and Wastes Resources

LIGHT POLLUTION COSTS MONEY AND WASTES RESOURCES Keep light on the HOW DOES ENERGY WASTE HARM THE ENVIRONMENT? ground Excess lighting pumps millions of tons of carbon into our atmosphere every year, and also causes light pollution. Light pollution: • Increases greenhouse gas emissions • Contributes to climate change • Increases our energy dependence WHAT ABOUT OUR CARBON FOOTPRINT? ENERGY EFFICIENCY SOLUTIONS In the U.S. alone, about 15 million tons of CO 2 Shielding outdoor lighting saves energy and are emitted each year to power money, reduces our carbon footprint and helps residential outdoor lighting. That protect the natural nighttime environment. The equals the emissions of about 3 HOW MUCH ENERGY AM I WASTING? solutions are easy. Work with your neighbors and million passenger cars and adds local government to keep the light on the ground up to 40,000 tons per day. To The average house with poorly designed and the skies natural. It’s a win-win for every- offset all that carbon dioxide, we’d outdoor lighting wastes 0.5 kilowatt- one. You save money while preserving a valuable need to plant about 600 million hours (kWh) per night. A kilowatt- natural resource. trees annually! hour is a unit of energy equivalent to one kilowatt of power for an hour. Tips to help you conserve energy and use light WHAT DOES LIGHT POLLUTION It’s enough energy to power a 50-inch efficiently: COST? plasma TV for one hour or run one load in • Install quality outdoor lighting to cut energy your dishwasher! About $3 billion dollars per year of energy is use by 60-70%, save money and cut carbon lost to bad lighting. -

Artificial Light at Night — the Impact on Plants and Ecology

Artificial light at night — the impact on plants and ecology Artificial light — such as street lighting and passing car headlights — has an impact on plants. A new study suggests there could also be broader implications for the interactions of herbivores and pollinators. The study highlights 06 May 2016 that disrupting seasonal light cues with artificial light has far-reaching effects, Issue 455 including: mismatches in timing with herbivores; altering the development of Subscribe to free agricultural crops; inhibiting flowering in wild species; decreasing periods of weekly News Alert darkness necessary for plant repair from environmental pollutants; and causing barriers to nocturnal pollinator species. Source: Bennie, J., Davies, T.W., Cruse, D. & Light is a vital requirement for plants: it is necessary for photosynthesis, for information Gaston, K.J. (2016). (i.e. when to bud, flower, germinate, etc.) and for their growth form. Natural light varies Ecological effects of daily and seasonally. Artificial light sources interrupt that natural cycle — and may disrupt artificial light at night on both the plants and the ecology they support. These manmade light sources are wild plants. Journal of concentrated along road verges and hedgerows, in gardens and in urban environments, Ecology. 104(3): 611–620. which may represent a significant and potentially hitherto overlooked threat. A new DOI:10.1111/1365- European-funded1 study poses the following questions: 1. How much artificial light is there 2745.12551 in the environment? 2. How do plants sense light? 3. How do plants respond to artificial light at night? Contact: [email protected] Artificial lights sources (e.g. -

Sustainable Lighting and Light Pollution: a Critical Issue for the Present Generation, a Challenge to the Future

sustainability Editorial Sustainable Lighting and Light Pollution: A Critical Issue for the Present Generation, a Challenge to the Future Georges Zissis LAPLACE UMR 5213 CNRS-INPT-UT3, Université de Toulouse, 118 route de Narbonne, 31062 Toulouse, CEDEX 9, France; [email protected] Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 29 May 2020; Published: 3 June 2020 Abstract: Human beings’ poor night vision and primitive fear of the dark are reflected in an imperative need to use artificial light to illuminate their environment. Outdoor illumination undoubtedly contributes to the enhancement of practical opportunities for social and economic developments. Considered as a necessity, a means of security, and an attraction or valorization, city lighting growth has been literally exponential in the last half century. Beyond the financial and energy resources that it absorbs, the artificial lighting of urban spaces overflows its objective by polluting our nights to the point that, in our modern megacities, the stars disappear. Apart from the fact that stars are no longer visible, the scientific community is increasingly interested in the direct and indirect impacts of artificial lighting on biodiversity. In parallel, some studies have shown recently that stray light may have direct or indirect effects on human health and mood. The scope of this Special Issue, dedicated to the memory of Prof. Abraham Haim and Dr. Thomas Posch, is to put together a series of high-level papers treating light pollution in a holistic manner that goes from technological advances to policies, passing through impacts on biotopes and human health. Beyond its evident scientific interest, this Special Issue is also contributing to awareness raising, aimed at decision- and policy-makers. -

Air, Water & Land Resource Quality

Goal 6 Air, Water & Land Resource Quality The residents of Benton County value clean air, water and healthy natural systems and recognize their importance in sustaining the quality of life that residents value for themselves, their children and grandchildren. Benton County Comprehensive Plan Value Statement Goal 6 Air, Water & Land Resource Quality Overview The maintenance and improvement of air, water and land resource quality are important considerations in all phases of land use management and planning. The policies in this section of the Plan provide the framework for evaluating land use actions for their potential impact on the county’s natural environment and guide the management of County operations, consistent with Benton County’s commitment to protecting these valuable resources. Cooperation among all levels of government and citizens is critical to protecting air, water and land resources. State and federal agencies, including the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), have a primary role in monitoring and enforcing quality standards. The policies in this chapter define the responsibility of the County to work in partnership with others to achieve the highest level of air, water and land resource quality. In developing these policies, the Steering Committee reviewed information provided by Benton County’s Environmental Health Department and by the Oregon Departments of Environmental Quality, Agriculture and Water Resources as well as relevant information included in the Environmental Quality Background Report of 1979. Marys River Adopted 2007 Benton County Comprehensive Plan page 6-1 Goal 6 Benton County Goal Statewide Planning Goal 6 Air, Water & Land Resource To maintain and improve the quality of the air, water Quality and land resources of the state.