Eyes of Youth 1919

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

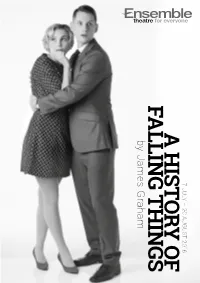

A H Ist Or Y of Fa Llin G T H In

7 JULY – 20 AUGUST 2016 A HISTORY OF FALLING THINGS by James Graham A HISTORY OF FALLING THINGS by James Graham PLAYWRIGHT DIRECTOR JAMES GRAHAM NICOLE BUFFONI CAST CREW ROBIN JACQUI DESIGNER ASSISTANT ERIC BEECROFT SOPHIE HENSSER ANNA GARDINER STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH LIGHTING LESLEY REECE DESIGNER WARDROBE MERRIDY BRIAN MEEGAN CHRISTOPHER PAGE COORDINATOR EASTMAN RENATA BESLIK AV DESIGNER JIMMY TIM HOPE DIALECT SAM O’SULLIVAN COACH SOUND DESIGNER NICK CURNOW ALISTAIR WALLACE JOHN REHEARSAL (VOICEOVER) STAGE OBSERVER MARK KILMURRY MANAGER ELSIE EDGERTON-TILL LARA QUALTROUGH PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY RUNNING TIME: APPROXIMATELY 90 MINUTES (NO INTERVAL) JAMES GRAHAM – PLAYWRIGHT James is a playwright and film Barlow. It opened in Boston in Summer 2014 and and television writer who won transferred to Broadway in Spring 2015. His play the Pearson Playwriting Bursary THE VOTE at the Donmar Warehouse aired in real in 2006 and went on to win the time on TV in the final 90 minutes of the 2015 Catherine Johnson Award for the Best Play in polling day and has been nominated for a BAFTA. 2007 for his play EDEN’S EMPIRE. James’ play His first film for television, CAUGHT IN A TRAP, was THIS HOUSE premièred at the Cottesloe Theatre broadcast on ITV1 on Boxing Day 2008. James was in September 2012, directed by Jeremy Herrin, and picked as one of Broadcast Magazine’s Hotshots transferred to the Olivier in 2013 where it enjoyed in the same year. He is developing original series a sell out run and garnered critical acclaim and and adaptations with Tiger Aspect, Leftbank, a huge amount of interest and admiration from Kudos and the BBC. -

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Film and Video 1 Audio 3 Printed Material 5 Professional Material 10 Correspondence 13 Financial Material 50 Manuscripts 50 Photographs 51 Personal Memorabilia 65 Scrapbooks 67 Fontaine, Joan #570 Box 1 No Folder I. Film and Video. A. Video cassettes, all VHS format except where noted. In date order. 1. "No More Ladies," 1935; "Tell Me the Truth" [1 tape]. 2. "No More Ladies," 1935; "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937; "Maid's Night Out," 1938; "The Selznick Years," 1969 [1 tape]. 3. "Music for Madam," 1937; "Sky Giant," 1938; "Maid's Night Out," 1938 [1 tape]. 4. "Quality Street," 1937. 5. "A Damsel in Distress," 1937, 2 copies. 6. "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937. 7. "Maid's Night Out," 1938. 8. "The Duke ofWestpoint," 1938. 9. "Gunga Din," 1939, 2 copies. 10. "The Women," 1939, 3 copies [4 tapes; 1 version split over two tapes.] 11. "Rebecca," 1940, 3 copies. 12. "Suspicion," 1941, 4 copies. 13. "This Above All," 1942, 2 copies. 14. "The Constant Nymph," 1943. 15. "Frenchman's Creek," 1944. 16. "Jane Eyre," 1944, 3 copies. 2 Box 1 cont'd. 17. "Ivy," 1947, 2 copies. 18. "You Gotta Stay Happy," 1948. 19. "Kiss the Blood Off of My Hands," 1948. 20. "The Emperor Waltz," 1948. 21. "September Affair," 1950, 3 copies. 22. "Born to be Bad," 1950. 23. "Ivanhoe," 1952, 2 copies. 24. "The Bigamist," 1953, 2 copies. 25. "Decameron Nights," 1952, 2 copies. 26. "Casanova's Big Night," 1954, 2 copies. -

Dossier De Presse ECLAIR

ECLAIR 1907 - 2007 du 6 au 25 juin 2007 Créés en 1907, les Studios Eclair ont constitué une des plus importantes compagnies de production du cinéma français des années 10. Des serials trépidants, des courts-métrages burlesques, d’étonnants films scientifiques y furent réalisés. Le développement de la société Eclair et le succès de leurs productions furent tels qu’ils implantèrent des filiales dans le monde, notamment aux Etats-Unis. Devenu une des principales industries techniques du cinéma français, Eclair reste un studio prisé pour le tournage de nombreux films. La rétrospective permettra de découvrir ou de redécouvrir tout un moment essentiel du cinéma français. En partenariat avec et Remerciements Les Archives Françaises du Film du CNC, Filmoteca Espa ňola, MoMA, National Film and Television Archive/BFI, Nederlands Filmmuseum, Library of Congress, La Cineteca del Friuli, Lobster films, Marc Sandberg, Les Films de la Pléiade, René Chateau, StudioCanal, Tamasa, TF1 International, Pathé. SOMMAIRE « Eclair, fleuron de l’industrie cinématographique française » p2-4 « 1907-2007 » par Marc Sandberg Autour des films : p5-6 SEANCE « LES FILMS D’A.-F. PARNALAND » Jeudi 7 juin 19h30 salle GF JOURNEE D’ETUDES ECLAIR Jeudi 14 juin, Entrée libre Programmation Eclair p7-18 Renseignements pratiques p19 La Kermesse héroïque de Jacques Feyder (1935) / Coll. CF, DR Contact presse Cinémathèque française Elodie Dufour - Tél. : 01 71 19 33 65 - [email protected] « Eclair, fleuron de l’industrie cinématographique française » « 1907-2007 » par Marc Sandberg Eclair, c’est l’histoire d’une remarquable ténacité industrielle innovante au service des films et de leurs auteurs, grâce à une double activité de studio et de laboratoire, s’enrichissant mutuellement depuis un siècle. -

The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Film Studies (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-2021 The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Michael Chian Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/film_studies_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chian, Michael. "The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood." Master's thesis, Chapman University, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000269 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film Studies (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood A Thesis by Michael Chian Chapman University Orange, CA Dodge College of Film and Media Arts Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies May, 2021 Committee in charge: Emily Carman, Ph.D., Chair Nam Lee, Ph.D. Federico Paccihoni, Ph.D. The Ben-Hur Franchise and the Rise of Blockbuster Hollywood Copyright © 2021 by Michael Chian III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor and thesis chair, Dr. Emily Carman, for both overseeing and advising me throughout the development of my thesis. Her guidance helped me to both formulate better arguments and hone my skills as a writer and academic. I would next like to thank my first reader, Dr. Nam Lee, who helped teach me the proper steps in conducting research and recognize areas of my thesis to improve or emphasize. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Fort Lee Booklet

New Jersey and the Early Motion Picture Industry by Richard Koszarski, Fort Lee Film Commission The American motion picture industry was born and raised in New Jersey. Within a generation this powerful new medium passed from the laboratories of Thomas Edison to the one-reel masterworks of D.W. Griffith to the high-tech studio town of Fort Lee with rows of corporate film factories scattered along the local trolley lines. Although a new factory town was eventually established on the West Coast, most of the American cinema’s real pioneers first paid their dues on the stages (and streets) of New Jersey. On February 25, 1888, the Photographer Eadweard Muybridge lectured on the art of motion photography at New Jersey’s Orange Music Hall. He demonstrated his Zoopraxiscope, a simple projector designed to reanimate the high-speed still photographs of human and animal subjects that had occupied him for over a decade. Two days later he visited Thomas Alva Edison at his laboratory in West Orange, and the two men discussed the possibilities of linking the Zoopraxiscope with Edison’s phonograph. Edison decided to proceed on his own and assigned direction of the project to his staff photographer, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson. In 1891 Dickson became the first man to record sequential photographic images on a strip of transparent celluloid film. Two years later, in anticipation of commercialization of the new process, he designed and built the first photographic studio intended for the production of motion pictures, essentially a tar paper shack mounted on a revolving turntable (to allow his subjects to face the direct light of the sun). -

Intimations Surnames L

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames L This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames L Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage L’AMY / SCOTT 1863 Sylvester L’Amy, London, to Margaret Sinclair, 2nd daughter of John Scott, Finnart, Greenock, at St George’s, London on 6th May 1863.. see Margaret S. (Greenock Advertiser 9.5.1863) Marriage LACHLAN / 1891 Alexander McLeod to Lizzie, youngest daughter of late MCLEOD James Lachlan, at Arcade Hall, Greenock on 5th February 1891 (Greenock Telegraph 09.02.1891) Marriage LACHLAN / SLATER 1882 Peter, eldest son of John Slater, blacksmith to Mary, youngest daughter of William Lachlan formerly of Port Glasgow at 9 Plantation Place, Port Glasgow on 21.04.1882. (Greenock Telegraph 24.04.1882) see Mary L Death LACZUISKY 1869 Maximillian Maximillian Laczuisky died at 5 Clarence Street, Greenock on 26th December 1869. -

In 1925, Eight Actors Were Dedicated to a Dream. Expatriated from Their Broadway Haunts by Constant Film Commitments, They Wante

In 1925, eight actors were dedicated to a dream. Expatriated from their Broadway haunts by constant film commitments, they wanted to form a club here in Hollywood; a private place of rendezvous, where they could fraternize at any time. Their first organizational powwow was held at the home of Robert Edeson on April 19th. ”This shall be a theatrical club of love, loy- alty, and laughter!” finalized Edeson. Then, proposing a toast, he declared, “To the Masquers! We Laugh to Win!” Table of Contents Masquers Creed and Oath Our Mission Statement Fast Facts About Our History and Culture Our Presidents Throughout History The Masquers “Who’s Who” 1925: The Year Of Our Birth Contact Details T he Masquers Creed T he Masquers Oath I swear by Thespis; by WELCOME! THRICE WELCOME, ALL- Dionysus and the triumph of life over death; Behind these curtains, tightly drawn, By Aeschylus and the Trilogy of the Drama; Are Brother Masquers, tried and true, By the poetic power of Sophocles; by the romance of Who have labored diligently, to bring to you Euripedes; A Night of Mirth-and Mirth ‘twill be, By all the Gods and Goddesses of the Theatre, that I will But, mark you well, although no text we preach, keep this oath and stipulation: A little lesson, well defined, respectfully, we’d teach. The lesson is this: Throughout this Life, To reckon those who taught me my art equally dear to me as No matter what befall- my parents; to share with them my substance and to comfort The best thing in this troubled world them in adversity. -

Download a PDF of This Article

34 MAY | JUNE 2016 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE Julian Wasser’s photographic love affair with Hollywood began more than half a century ago. He’s been loving and hating and shooting it ever since. WASSERWASSERWASSER By Samuel Hughes PHOTOGRAPHY BY JULIAN WASSER WORLDWORLDWORLDTHE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE MAY | JUNE 2016 35 Goin’ to à Go Go: Cool fans and hot cars at the Whisky à Go Go (1964, Life). one point during our long, “It always was,” he agrees. “I was in the careening, R-rated conversa- Navy, in San Diego. I came up here, and it At tion over lunch at La Scala was like Sodom and Gomorrah—a dream! Presto, I tell Julian Wasser C’55 that I I saw how everybody—guys and girls—they wish I could go back with him to some were all beautiful. I said, ‘Can I live here? of those early shoots in the Los Angeles How am I even gonna get a date?’” of his salad days. He assesses my sanity But you did all right, I say. through probing eyes. Then: “Do it!” “Yeah, well—the Sixties came along, Click. and that became my decade.” Click. “It was a golden age and a hopeful time,” he writes in the introduction to The Way Until a few months ago, Wasser wasn’t We Were: The Photography of Julian even a blip on my radar. Then in January Wasser, a coffee-table book of his work we got a call from David Pullman C’83 published two years ago by Damiani. [“Alumni Profiles,” April 1997]. -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI' The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties By Nancy McGuire Roche A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University May 2011 UMI Number: 3464539 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3464539 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: Dr. William Brantley, Committees Chair IVZUs^ Dr. Angela Hague, Read Dr. Linda Badley, Reader C>0 pM„«i ffS ^ <!LHaAyy Dr. David Lavery, Reader <*"*%HH*. a*v. Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department ;jtorihQfcy Dr. Michael D1. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: vW ^, &v\ DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the women of my family: my mother Mary and my aunt Mae Belle, twins who were not only "Rosie the Riveters," but also school teachers for four decades. These strong-willed Kentucky women have nurtured me through all my educational endeavors, and especially for this degree they offered love, money, and fierce support.