Toronto, Pt. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS/SONY in High Gear W/Japanese Market on Eve Ur Inch Disks Bow

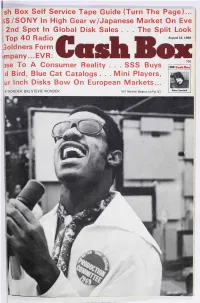

i sh Box Self Service Tape Guide (Turn The Page) ... IS/SONY In High Gear w/Japanese Market On Eve 2nd Spot In Global Disk Sales . The Split Look August 16, 1969 i Top 40 Radio ,;oldners Form ash.,mpany...EVR: )se To A Consumer Reality ... SSS Buys Ott Cash Box754 d Bird, Blue Cat Catalogs ... Mini Players, ur Inch Disks Bow On European Markets... Peter Sarstedt E WONDER: BIG STEVIE WONDER Intl Section Begins on Pg. 61 www.americanradiohistory.com The inevitable single from the group that brought you "Young Girl" and "WomanYVoman:' EC "This Girl Is Dir Ai STA BII aWoman Now7 hbAn. by Gary Puckett COiN and The Union Gap. DEE On Columbia Records* Di 3 II Lodz,' Tel: 11A fie 1%. i avb .» o www.americanradiohistory.com ///1\\ %b\\ ISM///1\\\ ///=1\\\ Min 111 111\ //Il11f\\ 11111111111111 1/11111 III111 MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY ii INTERNATIONAL milli 1IUUIII MI/I/ MIII II MU/// MUMi M1111/// U1111D U IULI glia \\\1197 VOL. XXXI - Number 3/August 16, 1969 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Cash Box Assoc. Editor JOHN KLEIN BOB COHEN BRUCE HARRIS Self- Service EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI ANTHONY LANZETTA Tape Guide ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER, New York BILL STUPER, New York HARVEY GELLER, Hollywood Much of the confusion facing first - 8 -TRACK CARTRIDGES: Using the WOODY HARDING unit tape consumers lies in the area same speed and thickness of tape Art Director of purchaser education. -

Score: a Hockey Musical

Mongrel Media Presents Score: A Hockey Musical A Film by Michael McGowan (92min., Canada, 2010) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html 1 OVERVIEW Music icon Olivia Newton-John (whose career has spanned over four decades, from Grease in 1978 to TV’s Glee in 2010) stars in Michael McGowan’s Score: A Hockey Musical, a film that combines musical numbers with Canada’s national sport. The film – which tells the story of a teenage hockey phenom who goes from obscurity to overnight fame – also stars a slew of Canadian talent. Among those are singer/songwriter Marc Jordan (whose composing credits include Rod Stewart’s “Rhythm of My Heart” and Cher’s “Taxi Taxi”), newcomers Noah Reid and Allie MacDonald, along with cameos by music artists Nelly Furtado, Dave Bidini, Hawksley Workman and John McDermott, journalists George Stroumboulopoulos and Evan Solomon, sports anchor Steve Kouleas, hockey dad Walter Gretzky and hockey star Theo Fleury. Unlike other musicals, the story doesn’t stop just for the sake of a song. Instead, the lyrics (written by McGowan) drive the plot. There are 20 original songs, among them one called “Darryl vs. the Kid” by Barenaked Ladies, as well as “Hugs” by Olivia Newton-John, Amy Sky and Marc Jordan, and five songs on which Hawksley Workman contributed. -

A Building Renos Start This Summer

I'M GOING NEWS ENTERTAINMENT OPINIONS TO THE An open letter to the students BEACH and Students' Association Board CALL ME IN SEPTEMBER. of Red River Community College Red River Community College May 25 - August 25, 1998 Volume 30• Issue 20 Changes on the way: A Building renos start this summer By Ross Romaniuk "The big firms adhere to a value - 10 N • kr 1 Staff Writer they want to give something back to their community," said TITANIC YOU ed River College Garbutt. O STUDENTS' ASSOCIATION is looking to the The campaign team, now num- bering about 40 volunteers, has private sector to RR been networking in and around Rcome through Winnipeg to drum up financial Volunteers and future students ofn Red River Community College thank you with the necessary funds for support since August of last year. for your support of the Vision Inovation Partnership Campaian---our first the College's first major Although the project is going established to fund Building, A renovations program facilities expan- well now, it got off to a slow gC College start. Many businesses were Community Red River majorwhich fund will raisingcreate a facility to tae education and Red River students into sion. reluctant to contribute to the Office take VIP Campaign The capital campaign to raise pri- Notre Dame Ave. College because 2055 A109 - vate funds for the upcoming they weren't aware of the range Winnipeg, MB R3H 039 the future. Phone: (204) 632-2011 Your support comes at an imporntgrowing time in demand the development for skilled andof the technologi- redevelopment of Building A has of programs it provides, 4859 - generated $1.35 million of the Fax: (204) 632 explained Garbutt. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE the Guess Who

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Guess Who will rock Tulalip Resort Casino in May 2019 TULALIP, WA – (January 25, 2019) – The Canadian rock band, The Guess Who, will be performing live in Tulalip Resort Casino’s Orca Ballroom on Friday, May 10. Formed in Winnipeg, The Guess Who initially gained recognition throughout Canada before becoming an international success in the late 1960s and 1970s. The Guess Who has enjoyed 14 Top 40 hits, including "These Eyes," "Clap For the Wolfman," "Hand Me Down World," "No Time," "Star Baby" and "Share the Land.” Additional classics include their number one rock anthem, "American Woman" and "No Sugar Tonight," plus "Laughing" and "Undun." The Guess Who are amongst music's most enduring bands and are eternally etched within the very fabric of pop culture history. Get up-close seating in the Orca Ballroom, an intimate 1,200-seat entertainment venue at Tulalip Resort Casino. Tickets go on sale Friday, March 15, at 10AM PST and start at $50. Tickets will be available for purchase on Ticketmaster.com or service charge free at the Tulalip Box Office. Must be 21+ to attend. About Tulalip Resort Casino Award-winning Tulalip Resort Casino is the most distinctive gaming, dining, meeting, entertainment and shopping destination in Washington State. The AAA Four-Diamond resort’s world-class amenities have ensured its place on the Condé Nast Traveler Gold and Traveler Top 100 Resorts lists. The property includes 192,000 square feet of gaming excitement; a luxury hotel featuring 370 guest rooms and suites; 30,000 square feet of premier meeting, convention and wedding space; the full-service T Spa; and eight dining venues. -

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

The Arts Page 8, the Retriever, April 28, 1975 / Cummings Laments on a Decade of 'Guess Who'

,.. The Arts Page 8, The Retriever, April 28, 1975 / Cummings laments on a decade of 'Guess Who' BY NEAL McGARITY Burton Cummings is the last original member writing better, more honest songs; of The Guess Who which began in the early whereas before we were writing songs 1960's. The band first came to prominence geared to the market more specifically. in 1965, when their song "Shakin' All Over" RETRIEVER: When the band first hit the Billboard top 20, Unable to follow formed, were there any intended goals? the latter songs' success, the band under· CUMMINGS: Well, I joined this group went some personnel changes, and toured when I was seventeen, and all I wanted throughout Canada widely, tightening them selves in the process_ The group re-appeared was a gold recoFd. Now I have a whole at the top of the charts in 1967 when house full of them. But I like going on the Cummings teamed with guitarist Rand~ Bach road and playing. There's a buzz that you man to write "These Eyes". After the success get from playing a really good gig that you of "These Eyes". Cummings found that every can't buy; and you can't get it from chicks song he touched turned to gold. "American or drugs or alcohol. Woman", "No Sugar Tonight", "No Time", RETRIEVER: Did you get a good buzz "Share the Land" and "Laughing" were just tonight? a few of the hits that followed. CUMMINGS: Oh yeah, definitely. We The band chugged easily "7Ilong on the played to twice as many as this last night, combination of Cummings' driving vocals and and they were just as receptive here Bachman) searing guitar work. -

The Cord Weekly

/ Laurier musicians Pierre Berton rock out at Wilf's visits Laurier Page Page THE , 2 CORD WEEKLY * Wednesday November 21, 2001 *Laurier's Official Student Newspaper • Volume 42 • Issue 15 2 News 6 Opinion 10 International 12 Feature 14 Entertainment 17 Sports 20 Student Life 22 Business 23 Classifieds More growing concerns "The reputation of Laurier has has also adversely affected WLU's She went on to say that many Students' Union requests an been tainted," said David public image, most notably in last more people accepted the offers of Wellhauser, Executive Vice week's Maclean's magazine univer- admission than in past years, a immediate freeze on current President of University Affairs. sity rankings. development that WLU was unable "Over-enrollment has had a nega- "WLU sent out too many offers to anticipate. The increase in enrollment levels tive effect on all students. It's irre- of admission," said Wellhauser. "It acceptances was most noticeable sponsible, and has to stop." was an irresponsible mistake that from students for whom Laurier MartinKuebler regarding the unexpected growth The Students' Union pointed should have been caught." was not a first choice. of Laurier's student body in recent to a number of reasons that have However, Undergraduate In order to properly address The issue of responsible growth at years. Of particular concern was contributed to over-crowding. Admissions Manager Gail Forsyth the growth situation, WLUSU pro- Laurier has not been given the what the Union called a "miscalcu- Among them are inadequate said the increased enrollment posed that current enrollment lev- "proper attention or recognition," lation in the admissions formula," provincial funding for universities experienced in 2001 was unfore- els be frozen immediately until stu- and the WLU Students' Union resulting in the surplus of 962 stu- and the deviation from the seeable, and was not as a result of dent concerns are addressed. -

Huntsville Town Council Resolution 338-15 on October 26, 2015

Town of Huntsville Staff Report Meeting Date: July 25, 2018 To: General Committee Report Number: CS-2018-24 Confidential: No Author(s): Teri Souter, Manager of Arts, Culture & Heritage Subject: Cultural Strategy Update Report Highlights • Cultural Strategic Plan update • Current internal/external situation review • Cultural Strategic visioning/inclusion encouraged for 2018-19 Recommendation That: Motion GC54-16 be rescinded; and Further That: the next term of Council be encouraged to consider an updated Cultural Strategy for the Corporation of the Town of Huntsville when identifying the Strategic Priorities for 2018-2022. Background The Town of Huntsville's Cultural Strategy 2011 contained 27 recommendations. Progress on the Cultural Strategy has been regularly reported. A status update "Culture Strategy Update" was presented to the Arts, Cultural and Heritage Advisory Committee on February 23, 2016: 25 of 27 goals were "finished/ongoing" and the remaining 2 were "started/needs attention." Some of the goals were completed or outdated. "Culture Strategy Direction" Report CS-2016-16 was then presented and Motion ACH8-16, including a commitment for community engagement and collaboration, was passed by the Advisory Committee: "The Manager of Arts, Culture & Heritage work via Advisory Committee, staff, sector professionals and stakeholders to draft a Huntsville Culture Strategy whitepaper, 2016 to 2019, to better reflect the direction of current council and to implement these directions." This motion was amended at General Committee on March 30, 2016. The amended motion GC54-16 is: "that The Manager of Arts Culture and Heritage work to draft a Huntsville Culture Strategy, 2016 to 2019, to better reflect the direction of current Council and further that the Manager of Arts, Culture and Heritage report back to committee." This was ratified via Council Resolution 94- 16, April 27, 2016. -

Ccy^EN Cat For

I Parrott loan plan under fire see page 5 Vo1.8> No .2 spats 0ally CMndna Luncheon Special! Entertainment Vol. 7. No. 2 MmmAupmMMv^mt EVERY FRIDAY Jan 16. 1978 All you can ccy^EN cat for $1.00 MM Humber College of Applied Arts & Technology -• ^ NO 1 Covea, MoMlay. Jan 16, 1978. Page Z Job forms 'discriminatory'— committee by Chris Van Krieken Revealing the age could also upset to find the present applica- married, they 11 leave to have tions. feel many people overlook result in discnmination, she said, tion applicants il Humber s Equal Opportunities asked to state children the fine print ^plaining ii. people be opposed to they Committee believes application because may were engaged. Even though the present applica- He views the deletion of the someone loo young or too forms m the personnel department hiring Ms Krakauer explained: If tion forms state applicants do not Items as "a positive move because old is are discriminatory. someone sees a person engaged, have to fill in this information. Bill there would be-little possibility for meniDers were The committee voted Jan 9 to Other committee the assumption is when they get Moore, director of personnel rela- abuse. recommend the college delete According to Mr. Moore, the col- from future applications such lege was brought before the items as marital status, date of Human Rights Commisssion birth, sex and number of depen- ponders changes several months ago because an ap- dent children Lakeshore SU plicant felt the college showed pre- According to Renate Krakauer, judicies. Number's senior program consul- Although Mr Moore refused to by Ann Kerr puses. -

Burton Cummings Mccallum Theatre Monday – February 24 – 7:00Pm

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 29, 2020 CONTACT: DeAnn Lubell-Ames – (760) 831-3090 Note: Photos available at http://mccallumtheatre.com/index.php/media Burton Cummings McCallum Theatre Monday – February 24 – 7:00pm Palm Desert, CA – Burton Cummings, one of the most successful music artists in Canadian history, will head down south to the McCallum Theatre for a special performance at 7:00pm, Monday, Feb. 24. Cummings is best known as the former lead singer of and songwriter for The Guess Who. He is a member of the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame, Canadian Music Industry Hall of Fame, Canadian Walk of Fame, Canadian Music Industry Hall of Fame and the Prairie Music Hall of Fame. He’s won multiple Juno Awards, and is a recipient of the Order of Canada, the Order of Manitoba, the Governor- General’s Performance Arts Award, and several BMI (Broadcast Music Industry) awards for more than 1 million airplays of his songs. With Canada’s original rock ’n’ roll superstars The Guess Who, Burton scored an unprecedented string of international hit singles, including “These Eyes,” “Laughing,” “No Time,” “American Woman,” “Share the Land,” “Hang on to Your Life,” “Albert Flasher,” “Sour Suite,” “Glamour Boy,” “Star Baby,” “Clap for the Wolfman” and “Dancin’ Fool”—all written or co-written by Burton. By 1970, The Guess Who had sold more records than the entire Canadian music industry combined to that point, and the band’s achievements remain unparalleled. The group notched up a long list of firsts, including being the first Canadian group to reach No. -

Marking 50 Years Since the Niverville Pop Festival

LOCAL NEWS The Party of the Century: Marking 50 Years Since the Niverville Pop Festival May 07, 2020 @ 12:30am Brenda Sawatzky [email protected] Crowds gather for the infamous Niverville Pop Festival in May 1970. On stage: Dianne Heatherington. Photo: Hans Sipma The hippie movement was alive and well in 1970, riding on the waves of the 1967 Summer of Love where more than a hundred thousand hippies converged on San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district to celebrate counterculture music, drugs, free love, and anti-war sentiment. In 1969, Woodstock, New York became famous for its three days of peace and music. Nine months later, hippies would once again amass—this time at a setting much closer to home. This local music event would go down in history not just for the calibre of bands scheduled to play but the memorable events that followed. Sunday, May 24, 1970 was the day of the Niverville Pop Festival. Niverville’s Woodstock During the 1960s and 70s, Winnipeg was a hotbed of young musical talent. One of those bands, called Brother, was quickly rising in notoriety. Its members included Bill Wallace, Kurt Winter, and Vance Masters, and their talent established them as one of the city’s hottest supergroups. Harold Wiebe, formerly of the Niverville area, recalls a night spent in the pub of the Westminster Hotel. There, friend and band member Bill Wallace joined him for a drink between sets. Wallace shared with him an idea to recreate Woodstock right here at home. But unlike Woodstock, Wallace wanted this event to have a charitable purpose. -

KREVISS Cargo Records Thanks WW DISCORDER and All Our Retail Accounts Across the Greater Vancouver Area

FLAMING LIPS DOWN BY LWN GIRL TROUBLE BOMB ATOMIC 61 KREVISS Cargo Records thanks WW DISCORDER and all our retail accounts across the greater Vancouver area. 1992 was a good year but you wouldn't dare start 1993 without having heard: JESUS LIZARD g| SEBADOH Liar Smash Your Head IJESUS LIZARD CS/CD On The Punk Rock CS/CD On Sebadoh's songwriter Lou Barlow:"... (his) songwriting sticks to your gullet like Delve into some raw cookie dough, uncharted musical and if he ever territory. overcomes his fascination with the The holiday season sound of his own being the perfect nonsense, his time for this baby Sebadoh could be from Jesus Lizard! the next greatest band on this Hallelujah! planet". -- Spin ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT Circa: Now! CS/CD/LP San Diego's saviour of Rock'n'Roll. Forthe ones who Riff-driven monster prefer the Grinch tunes that are to Santa Claus. catchier than the common cold and The most brutal, loud enough to turn unsympathetic and your speakers into a sickeningly repulsive smoldering heap of band ever. wood and wires. A must! Wl Other titles from these fine labels fjWMMgtlllli (roue/a-GO/ are available through JANUARY 1993 "I have a responsibility to young people. They're OFFICE USE ONLY the ones who helped me get where I am today!" ISSUE #120 - Erik Estrada, former CHiPs star, now celebrity monster truck commentator and Anthony Robbins supporter. IRREGULARS REGULARS A RETROSPECT ON 1992 AIRHEAD 4 BOMB vs. THE FLAMING LIPS COWSHEAD 5 SHINDIG 9 GIRL TROUBLE SUBTEXT 11 You Don't Go To Hilltop, You VIDEOPHILTER 21 7" T\ REAL LIVE ACTION 25 MOFO'S PSYCHOSONIC PIX 26 UNDER REVIEW 26 SPINLIST.