Poetics, Performance, and Translation in Eastern Cherokee Language Revitalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

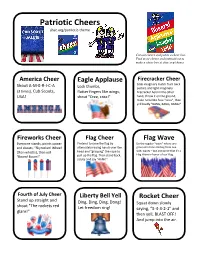

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Cherokee Ethnogenesis in Southwestern North Carolina

The following chapter is from: The Archaeology of North Carolina: Three Archaeological Symposia Charles R. Ewen – Co-Editor Thomas R. Whyte – Co-Editor R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. – Co-Editor North Carolina Archaeological Council Publication Number 30 2011 Available online at: http://www.rla.unc.edu/NCAC/Publications/NCAC30/index.html CHEROKEE ETHNOGENESIS IN SOUTHWESTERN NORTH CAROLINA Christopher B. Rodning Dozens of Cherokee towns dotted the river valleys of the Appalachian Summit province in southwestern North Carolina during the eighteenth century (Figure 16-1; Dickens 1967, 1978, 1979; Perdue 1998; Persico 1979; Shumate et al. 2005; Smith 1979). What developments led to the formation of these Cherokee towns? Of course, native people had been living in the Appalachian Summit for thousands of years, through the Paleoindian, Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippi periods (Dickens 1976; Keel 1976; Purrington 1983; Ward and Davis 1999). What are the archaeological correlates of Cherokee culture, when are they visible archaeologically, and what can archaeology contribute to knowledge of the origins and development of Cherokee culture in southwestern North Carolina? Archaeologists, myself included, have often focused on the characteristics of pottery and other artifacts as clues about the development of Cherokee culture, which is a valid approach, but not the only approach (Dickens 1978, 1979, 1986; Hally 1986; Riggs and Rodning 2002; Rodning 2008; Schroedl 1986a; Wilson and Rodning 2002). In this paper (see also Rodning 2009a, 2010a, 2011b), I focus on the development of Cherokee towns and townhouses. Given the significance of towns and town affiliations to Cherokee identity and landscape during the 1700s (Boulware 2011; Chambers 2010; Smith 1979), I suggest that tracing the development of towns and townhouses helps us understand Cherokee ethnogenesis, more generally. -

Northern Corridor Area Plan Is the Result of This Targeted Planning Study

Northern Corridor Area Plan Adopted by the Bradley County Regional Planning Commission Adoption Date: February 11, 2014 This page intentionally left blank. PLAN OVERVIEW 1 Overview ......................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: AREA PROFILE 3 Overview ......................................................................................................... 3 Geographic Profile & Character ............................................................. 3 Infrastructure & Facilities Overview ................................................... 4 Capacity for Growth .................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 2: TARGETED PLANNING CHALLENGES 7 Overview ......................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 3: MASTER PLAN 11 Overview ......................................................................................................... 11 Plan Vision ...................................................................................................... 11 Plan Goals........................................................................................................ 12 The Northern Corridor Area Master Plan Maps .............................. 13 Future Land Use Recommendations .................................................... 16 Future Land Use Focus Areas .................................................................. 24 Future Transportation Routes............................................................... -

Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2017 Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves Beau Duke Carroll University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Carroll, Beau Duke, "Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Beau Duke Carroll entitled "Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Jan Simek, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David G. Anderson, Julie L. Reed Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Beau Duke Carroll December 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Beau Duke Carroll All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the following people who contributed their time and expertise. -

American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) Honors Program 2005 Using space to describe space: American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis Cindee Calton University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2005 - Cindee Calton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst Part of the American Sign Language Commons Recommended Citation Calton, Cindee, "Using space to describe space: American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis" (2005). Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006). 56. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pst/56 This Open Access Presidential Scholars Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presidential Scholars Theses (1990 – 2006) by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Using Space to Describe Space: American Sign Language and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Cindee Calton University of Northern Iowa Undergraduate Research April 2005 Faculty Advisor, Dr. Cynthia Dunn - - - -- - Abstract My study sought to combine two topics that have recently generated much interest among anthropologists. One of these topics is American Sign Language, the other is linguistic relativity. Although both topics have been a part of the literature for some time, neither has been studied extensively until the recent past. Both present exciting new horizons for understanding culture, particularly language and culture. The first of these two topics is the study of American Sign Language. The reason for its previous absence from the literature has to do with unfortunate prejudice which, for a long time, kept ASL from being recognized as a legitimate language. -

USET SPF Resolution No. 2017 SPF:008 NATIONAL HEALTH

USET SPF Resolution No. 2017 SPF:008 NATIONAL HEALTH RELATED COMMITTEE AND WORKGROUP APPOINTMENTS WHEREAS, United South and Eastern Tribes Sovereignty Protection Fund (USET SPF) is an intertribal organization comprised of twenty-six (26) federally recognized Tribal Nations; and WHEREAS, the actions taken by the USET SPF Board of Directors officially represent the intentions of each member Tribal Nation, as the Board of Directors comprises delegates from the member Tribal Nations’ leadership; and WHEREAS, the United States (U.S.) Government and each federally recognized Tribal Nation has a government-to-government relationship grounded in numerous historical, political, legal, moral, and ethical considerations; and WHEREAS, it is essential that Tribal Nations and U.S. Departments/Operating Divisions engage in open continuous, and meaningful consultation; and WHEREAS, the importance of Tribal consultation with Indian Tribal Governments was affirmed through Presidential Memoranda (1994, 2004 & 2009) and a subsequent Executive Order (2000); and WHEREAS, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was the first to develop and implement a Tribal consultation process under the Presidential directives; and WHEREAS, the development of a Tribal consultation process was completed with direct involvement of Tribal Nation representatives, including USET staff; and WHEREAS, a variety of committees/workgroups have been developed to facilitate meaningful consultation with Tribal governments on issues that impact them and to promote Tribal Nation participation in the decision making process to the greatest extent possible; and WHEREAS, in December 2010, the United States recognized the rights of its First Peoples through its support of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), whose provisions and principles support and promote the purposes of this resolution; therefore, be it USET SPF Resolution No. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The Effect of Decolonization of the North Carolina American History I Curriculum from the Indigenous Perspective

THE EFFECT OF DECOLONIZATION OF THE NORTH CAROLINA AMERICAN HISTORY I CURRICULUM FROM THE INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation by HEATH RYAN ROBERTSON Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies At Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2021 Educational Leadership Doctoral Program Reich College of Education THE EFFECT OF DECOLONIZATION OF THE NORTH CAROLINA AMERICAN HISTORY I CURRICULUM FROM THE INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation by HEATH RYAN ROBERTSON May 2021 APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ Barbara B. Howard, Ed.D. Chairperson, Dissertation Committee _________________________________________ William M. Gummerson, Ph.D. Member, Dissertation Committee _________________________________________ Kimberly W. Money, Ed.D. Member, Dissertation Committee _________________________________________ Freeman Owle, M.Ed. Member, Dissertation Committee _________________________________________ Vachel Miller, Ed.D. Director, Educational Leadership Doctoral Program _________________________________________ Mike J. McKenzie, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies Copyright by Heath Ryan Robertson 2021 All Rights Reserved Abstract THE EFFECT OF DECOLONIZATION OF THE NORTH CAROLINA AMERICAN HISTORY I CURRICULUM FROM THE INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE Heath Ryan Robertson A.A., Southwestern Community College B.A., Appalachian State University MSA., Appalachian State University School Leadership Graduate Certificate, Appalachian State University -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

The Language of Humor: Navajo Ruth E. Cisneros, Joey Alexanian, Jalon

The Language of Humor: Navajo Ruth E. Cisneros, Joey Alexanian, Jalon Begay, Megan Goldberg University of New Mexico 1. Introduction We all laugh at jokes, exchange humorous stories for entertainment and information, tease one another, and trade clever insults for amusement on a daily basis. Scientists have told us that laughing is good for our health. But what makes something funny? Prior definitions of humor, like this one by Victor Raskin (1985), have categorized humor as a universal human trait: "responding to humor is part of human behavior, ability or competence, other parts of which comprise such important social and psychological manifestations of homo sapiens as language, morality, logic, faith, etc. Just as all of those, humor may be described as partly natural and partly acquired" (Raskin 1985: 2). The purpose and end result of humor, much like that of language, is the externalization of human thought and conceptualization. This externalization carries multiple meanings, partly as an outlet to express certain emotions, partly as a social device, and partly as an exercise of the intellect. The active engagement of this human ability allows some to earn their livelihood from a career in making jokes. Thus, there is the possibility in a culture to broadcast one’s own personal opinion and world view in a series of jokes. Chafe explains that this is an intrinsic attribute of Homo sapiens; it is "The essence of human understanding: the ability to interpret particular experiences as manifestations of lager encompassing systems" (1994: 9). Humor acts to level the field, allowing people who identify with each other to create social groups. -

Creating a Sense of Communityamong the Capital City Cherokees

CREATING A SENSE OF COMMUNITYAMONG THE CAPITAL CITY CHEROKEES by Pamela Parks Tinker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ____________________________________ Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Program Director ____________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date:________________________________ Spring 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Creating a Sense Of Community Among Capital City Cherokees A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies at George Mason University By Pamela Parks Tinker Bachelor of Science Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University 1975 Director: Meredith H. Lair, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Copyright 2016 Pamela Parks Tinker All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Thanks to the Capital City Cherokee Community for allowing me to study the formation of the community and for making time for personal interviews. I am grateful for the guidance offered by my Thesis Committee of three professors. Thesis Committee Chair, Professor Maria Dakake, also served as my advisor over a period of years in planning a course of study that truly has been interdisciplinary. It has been a joyful situation to be admitted to a variety of history, religion and spirituality, folklore, ethnographic writing, and research courses under the umbrella of one Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies program. Much of the inspiration for this thesis occurred at George Mason University in Professor Debra Lattanzi Shutika’s Folklore class on “Sense of Place” in which the world of Ethnography opened up for me. -

Seal of the Cherokee Nation

Chronicles of Ohhorna SEAL OF THE CHEROKEE NATION A reproduction in colors of the Seal of the Cherokee Nation appears on the front coyer of this summer number of The Chronicles, made from the original painting in the Museum of the Oklahoma Historical Society.' The official Cherokee Seal is centered by a large seven-pointed star surrounded by a wreath of oak leaves, the border encircling this central device bearing the words "Seal of the Cherokee Nation" in English and seven characters of the Sequoyah alphabet which form two words in Cherokee. These seven charactem rspresenting syllables from Sequoyah's alphabet are phonetically pronounced in English ' ' Tw-la-gi-hi A-ye-li " and mean " Cherokee Nation" in the native language. At the lower part of the circular border is the date "Sept. 6, 1839," that of the adoption of the Constitution of the Cherokee Nation, West. Interpretation of the de~icein this seal is found in Cherokee folklore and history. Ritual songs in certain ancient tribal cere- monials and songs made reference to seven clans, the legendary beginnings of the Cherokee Nation whose country early in the historic period took in a wide area now included in the present eastern parts of Tennessee and Kentucky, the western parts of Virginia and the Carolinas, as well as extending over into what are now northern sections of Georgia and Alabama. A sacred fire was kept burning in the "Town House" at a central part of the old nation, logs of the live oak, a hardwood timber in the region, laid end to end to keep the fire going.