Losing Chess Endgame Material to 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Combinatorial Game Theoretic Analysis of Chess Endgames

A COMBINATORIAL GAME THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF CHESS ENDGAMES QINGYUN WU, FRANK YU,¨ MICHAEL LANDRY 1. Abstract In this paper, we attempt to analyze Chess endgames using combinatorial game theory. This is a challenge, because much of combinatorial game theory applies only to games under normal play, in which players move according to a set of rules that define the game, and the last player to move wins. A game of Chess ends either in a draw (as in the game above) or when one of the players achieves checkmate. As such, the game of chess does not immediately lend itself to this type of analysis. However, we found that when we redefined certain aspects of chess, there were useful applications of the theory. (Note: We assume the reader has a knowledge of the rules of Chess prior to reading. Also, we will associate Left with white and Right with black). We first look at positions of chess involving only pawns and no kings. We treat these as combinatorial games under normal play, but with the modification that creating a passed pawn is also a win; the assumption is that promoting a pawn will ultimately lead to checkmate. Just using pawns, we have found chess positions that are equal to the games 0, 1, 2, ?, ", #, and Tiny 1. Next, we bring kings onto the chessboard and construct positions that act as game sums of the numbers and infinitesimals we found. The point is that these carefully constructed positions are games of chess played according to the rules of chess that act like sums of combinatorial games under normal play. -

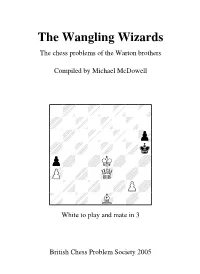

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1 “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION 2013, Botswana Chess Review In this Issue; BY: KEENESE NEOYAME KATISENGE 1. Historic World Chess Federation’s Visit to Botswana 2. Field Performance 3. Administration & Developmental Programs BCF PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTOR 4. Social Responsibility, Marketing and Publicity / Sponsorships B “Checkmate” is the first edition of BCF e-Newsletter. It will be released on a quarterly basis with a review of chess events for the past period. In Chess circles, “Checkmate” announces the end of the game the same way this newsletter reviews performance at the end of a specified period. The aim of “Checkmate” is to maintain contact with all stakeholders, share information with interesting chess highlights as well as increase awareness in a BNSC Chair Solly Reikeletseng,Mr Mogotsi from Debswana, cost-effective manner. Mr Bobby Gaseitsewe from BNSC and BCF Exo during The 2013 Re-ba bona-ha Youth Championships 2013, Botswana Chess Review Under the leadership of the new president, Tshenolo Maruatona,, Botswana Chess continues to steadily Minister of Youth, Sports & Culture Hon. Shaw Kgathi and cement its place as one of the fastest growing the FIDE Delegation during their visit to Botswana in 2013 sporting codes in the country. BCF has held a number of activities aimed at developing and growing the sport in the country. “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION | Issue 1 2 2013 Review Cont.. The president of the federation, Mr Maruatona attended two key International Congresses, i.e Zonal Meeting held during The -

Solved Openings in Losing Chess

1 Solved Openings in Losing Chess Mark Watkins, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Sydney 1. INTRODUCTION Losing Chess is a chess variant where each player tries to lose all one’s pieces. As the naming of “Giveaway” variants has multiple schools of terminology, we state for definiteness that captures are compulsory (a player with multiple captures chooses which to make), a King can be captured like any other piece, Pawns can promote to Kings, and castling is not legal. There are competing rulesets for stalemate: International Rules give the win to the player on move, while FICS (Free Internet Chess Server) Rules gives the win to the player with fewer pieces (and a draw if equal). Gameplay under these rulesets is typically quite similar.1 Unless otherwise stated, we consider the “joint” FICS/International Rules, where a stalemate is a draw unless it is won under both rulesets. There does not seem to be a canonical place for information about Losing Chess. The ICGA webpage [H] has a number of references (notably [Li]) and is a reasonable historical source, though the page is quite old and some of the links are broken. Similarly, there exist a number of piecemeal Internet sites (I found the most useful ones to be [F1], [An], and [La]), but again some of these have not been touched in 5-10 years. Much of the information was either outdated or tangential to our aim of solving openings (in particular responses to 1. e3), We started our work in late 2011. The long-term goal was to weakly solve the game, presumably by showing that 1. -

UIL Text 111212

UIL Chess Puzzle Solvin g— Fall/Winter District 2016-2017 —Grades 4 and 5 IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: [Test-administrators, please read text in this box aloud.] This is the UIL Chess Puzzle Solving Fall/Winter District Test for grades four and five. There are 20 questions on this test. You have 30 minutes to complete it. All questions are multiple choice. Use the answer sheet to mark your answers. Multiple choice answers pur - posely do not indicate check, checkmate, or e.p. symbols. You will be awarded one point for each correct answer. No deductions will be made for incorrect answers on this test. Finishing early is not rewarded, even to break ties. So use all of your time. Some of the questions may be hard, but all of the puzzles are interesting! Good luck and have fun! If you don’t already know chess notation, reading and referring to the section below on this page will help you. How to read and answer questions on this test Piece Names Each chessman can • To answer the questions on this test, you’ll also be represented need to know how to read chess moves. It’s by a symbol, except for the pawn. simple to do. (Figurine Notation) K King Q • Every square on the board has an “address” Queen R made up of a letter and a number. Rook B Bishop N Knight Pawn a-h (We write the file it’s on.) • To make them easy to read, the questions on this test use the figurine piece symbols on the right, above. -

Bibliography of Traditional Board Games

Bibliography of Traditional Board Games Damian Walker Introduction The object of creating this document was to been very selective, and will include only those provide an easy source of reference for my fu- passing mentions of a game which give us use- ture projects, allowing me to find information ful information not available in the substan- about various traditional board games in the tial accounts (for example, if they are proof of books, papers and periodicals I have access an earlier or later existence of a game than is to. The project began once I had finished mentioned elsewhere). The Traditional Board Game Series of leaflets, The use of this document by myself and published on my web site. Therefore those others has been complicated by the facts that leaflets will not necessarily benefit from infor- a name may have attached itself to more than mation in many of the sources below. one game, and that a game might be known Given the amount of effort this document by more than one name. I have dealt with has taken me, and would take someone else to this by including every name known to my replicate, I have tidied up the presentation a sources, using one name as a \primary name" little, included this introduction and an expla- (for instance, nine mens morris), listing its nation of the \families" of board games I have other names there under the AKA heading, used for classification. and having entries for each synonym refer the My sources are all in English and include a reader to the main entry. -

Шахматных Задач Chess Exercises Schachaufgaben

Всеволод Костров Vsevolod Kostrov Борис Белявский Boris Beliavsky 2000 Шахматных задач Chess exercises Schachaufgaben РЕШЕБНИК TACTICAL CHESS.. EXERCISES SCHACHUBUNGSBUCH Шахматные комбинации Chess combinations Kombinationen Часть 1-2 разряд Part 1700-2000 Elo 3 Teil 1-2 Klasse Русский шахматный дом/Russian Chess House Москва, 2013 В первых двух книжках этой серии мы вооружили вас мощными приёмами для успешного ведения шахматной борьбы. В вашем арсенале появились двойной удар, связка, завлечение и отвлечение. Новый «Решебник» обогатит вас более изысканным тактическим оружием. Не всегда до короля можно добраться, используя грубую силу. Попробуйте обхитрить партнёра с помощью плаща и кинжала. Маскируйтесь, как разведчик, и ведите себя, как опытный дипломат. Попробуйте найти слабое место в лагере противника и в нужный момент уничтожьте защиту и нанесите тонкий кинжальный удар. Кстати, чужие фигуры могут стать союзниками. Умелыми манёврами привлеките фигуры противника к их королю, пускай они его заблокируют так, чтобы ему, бедному, было не вздохнуть, и в этот момент нанесите решающий удар. Неприятно, когда все фигуры вашего противника взаимодействуют между собой. Может, стоить вбить клин в их порядки – перекрыть их прочной шахматной дверью. А так ли страшна атака противника на ваши укрепления? Стоит ли уходить в глухую оборону? Всегда ищите контрудар. Тонкий промежуточный укол изменит ход борьбы. Не сгрудились ли ваши фигуры на небольшом пространстве, не мешают ли они друг другу добраться до короля противника? Решите, кому всё же идти на штурм королевской крепости, и освободите пространство фигуре для атаки. Короля всегда надо защищать в первую очередь. Используйте это обстоятельство и совершите открытое нападение на него и другие фигуры. И тогда жернова вашей «мельницы» перемелют всё вражеское войско. -

Download Preview

ISSUE 7 MODERN CHESS MAGAZINE Farewell, Viktor Endgame Sicilian Structures – Series - Part 7 Part 2 Strong Knight Methods of Against Bad Bishop Playing against in the Endgame Semi-Hanging Pawns GM Repertoire Against 1.d4 – Part 3 Table of contents 3 Farewell, Viktor 5 Gavrikov,Viktor (2550) - Gulko,Boris F (2475) 7 Strong Knight Against Bad Bishop in the Endgames (GM Viktor Gavrikov) 7 Educational example 8 Zubarev,N - Aleksandrov,NMoskow, 1915 10 Almasi,Zoltan (2630) - Zueger,Beat (2470) Horgen-B Horgen (6), 1995 11 Torre,E - Jakobsen,O Amsterdam, 1973 14 Methods of Playing against Semi-Hanging Pawns (GM Grigor Grigorov) 15 Rubinstein,Akiba - Salwe,Georg Lodz mt Lodz, 1908 17 Gavrikov,Viktor Nikolaevich (2450) - Mochalov,Evgeny V (2420) LTU-ch open Vilnius (10), 15.03.1983 18 Flohr,Salo - Vidmar,Milan Sr Nottingham Nottingham, 1936 21 Petrosian,Tigran Vartanovich - Smyslov,Vassily Moscow tt, 1961 22 Kramnik,Vladimir (2710) - Illescas Cordoba,Miguel (2590) Linares 12th Linares (6), 1994 24 GM Repertoire against 1.d4 – Part 3 (GM Boris Chatalbashev) 24 Zhigalko,Sergei (2656) - Petrov,Marijan (2535) 26 Arkhipov,Sergey (2465) - Kuzmin,Alexey (2465) Moscow1 Moscow, 1989 28 Nikolov,Momchil (2550) - Chatalbashev,Boris (2555) 30 Kortschnoj,Viktor (2643) - Chatalbashev,Boris (2518) EU-ch 2nd Ohrid (2), 02.06.2001 33 Taras,I (2267) - Chatalbashev,B (2591) 19th Albena Open Albena BUL (8.22), 02.07.2011 Sicilian Structures – Part 2. How To Fight For The Weak d5-square 34 (GM Petar G. Arnaudov) 34 Smyslov,Vassily - Rudakovsky,Iosif URS-ch14 Moscow, -

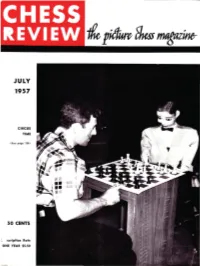

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Colorado Chess Informant

Volume 39, Number 3 July 2012 / $3.00 Colorado State Chess Association COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT Photo by Michael Wokurka Grandmaster Tejas Bakre receiving his prize winnings from Organizer, Joe Fromme. Grandmaster In The House! Bobby Fischer Saluted www.colorado-chess.com Volume 39, Number 3 Colorado Chess Informant July 2012 From The Editor Whew, it has been a busy past few months for chess in Colorado. When the membership voted to go to an all electronic issue of the Informant, that gave me the ability to expand an issue as The Colorado State Chess Junior Representative: much as the number of articles allowed without incurring any Association, Inc., is a Section Rhett Langseth cost to the CSCA. 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non- 15282 Paddington Circle 44 pages of chess in Colorado awaits you in this issue! That profit educational corporation Colorado Springs, CO 80921 should keep you busy for the next three months. The feature of formed to promote chess in [email protected] this issue is the wonderful “Salute to Bobby Fischer Chess Tour- Colorado. Contributions are Members at Large: nament” that was held in early May and which I was once again tax deductible. Dues are $15 a Frank Deming honored by the Organizer, Joe Fromme, in having selected me as year or $5 a tournament. Youth 7906 Eagle Ranch Road the Tournament Director. Again a premier event all around and (under 21) and Senior (65 or Fort Collins, CO 80528 even more so when we had the pleasure of hosting Grandmaster older) memberships are $10. [email protected] Tejas Bakre from India, who decided to play. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH)

No. 123 - (Vol.VIH) January 1997 Editorial Board editors John Roycrqfttf New Way Road, London, England NW9 6PL Edvande Gevel Binnen de Veste 36, 3811 PH Amersfoort, The Netherlands Spotlight-column: J. Heck, Neuer Weg 110, D-47803 Krefeld, Germany Opinions-column: A. Pallier, La Mouziniere, 85190 La Genetouze, France Treasurer: J. de Boer, Zevenenderdrffi 40, 1251 RC Laren, The Netherlands EDITORIAL achievement, recorded only in a scientific journal, "The chess study is close to the chess game was not widely noticed. It was left to the dis- because both study and game obey the same coveries by Ken Thompson of Bell Laboratories rules." This has long been an argument used to in New Jersey, beginning in 1983, to put the boot persuade players to look at studies. Most players m. prefer studies to problems anyway, and readily Aside from a few upsets to endgame theory, the give the affinity with the game as the reason for set of 'total information' 5-raan endgame their preference. Your editor has fought a long databases that Thompson generated over the next battle to maintain the literal truth of that ar- decade demonstrated that several other endings gument. It was one of several motivations in might require well over 50 moves to win. These writing the final chapter of Test Tube Chess discoveries arrived an the scene too fast for FIDE (1972), in which the Laws are separated into to cope with by listing exceptions - which was the BMR (Board+Men+Rules) elements, and G first expedient. Then in 1991 Lewis Stiller and (Game) elements, with studies firmly identified Noam Elkies using a Connection Machine with the BMR realm and not in the G realm.