For Peer Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PH 'Wessex White Horses'

Notes from a Preceptor’s Handbook A Preceptor: (OED) 1440 A.D. from Latin praeceptor one who instructs, a teacher, a tutor, a mentor “A horse, a horse and they are all white” Provincial Grand Lodge of Wiltshire Provincial W Bro Michael Lee PAGDC 2017 The White Horses of Wessex Editors note: Whilst not a Masonic topic, I fell Michael Lee’s original work on the mysterious and mystical White Horses of Wiltshire (and the surrounding area) warranted publication, and rightly deserved its place in the Preceptors Handbook. I trust, after reading this short piece, you will wholeheartedly agree. Origins It seems a perfectly fair question to ask just why the Wiltshire Provincial Grand Lodge and Grand Chapter decided to select a white horse rather than say the bustard or cathedral spire or even Stonehenge as the most suitable symbol for the Wiltshire Provincial banner. Most continents, most societies can provide examples of the strange, the mysterious, that have teased and perplexed countless generations. One might include, for example, stone circles, ancient dolmens and burial chambers, ley lines, flying saucers and - today - crop circles. There is however one small area of the world that has been (and continues to be) a natural focal point for all of these examples on an almost extravagant scale. This is the region in the south west of the British Isles known as Wessex. To our list of curiosities we can add yet one more category dating from Neolithic times: those large and mysterious figures dominating our hillsides, carved in the chalk and often stretching in length or height to several hundred feet. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

The Geoglyphs of Har Karkom (Negev, Israel): Classification and Interpretation

PAPERS XXIV Valcamonica Symposium 2011 THE GEOGLYPHS OF HAR KARKOM (NEGEV, ISRAEL): CLASSIFICATION AND INTERPRETATION Federico Mailland* Abstract - The geoglyphs of Har Karkom (Negev, Israel): classification and interpretation There is a debate on the possible interpretation of geoglyphs as a form of art, less durable than rock engravings, picture or sculpture. Also, there is a debate on how to date the geoglyphs, though some methods have been proposed. Har Karkom is a rocky mountain, a mesa in the middle of what today is a desert, a holy mountain which was worshipped in the prehis- tory. The flat conformation of the plateau and the fact that it was forbidden to the peoples during several millennia allowed the preservation of several geoglyphs on its flat ground. The geoglyphs of Har Karkom are drawings made on the surface by using pebbles or by cleaning certain areas of stones and other surface rough features. Some of the drawings are over 30 m long. The area of Har Karkom plateau and the southern Wadi Karkom was surveyed and zenithal pictures were taken by means of a balloon with a hanging digital camera. The aerial survey of Har Karkom plateau has reviewed the presence of about 25 geoglyph sites concentrated in a limited area of no more than 4 square km, which is considered to have been a sacred area at the time the geoglyphs were produced and defines one of the major world concentrations of this kind of art. The possible presence among the depictions of large mammals, such as elephant and rhino, already extinct in the area since late Pleistocene, may imply a Palaeolithic dating for some of the pebble drawings, which would make them the oldest pebble drawings known so far. -

Welcome to Wantage

WELCOME TO WANTAGE Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com Welcome to Wantage in Oxfordshire. Our local guide is your essential tool to everything going on in the town and surrounding area. Wantage is a picturesque market town and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse and is ideally located within easy reach of Oxford, Swindon, Newbury and Reading – all of which are less than twenty miles away. The town benefits from a wealth of shops and services, including restaurants, cafés, pubs, leisure facilities and open spaces. Wantage’s links with its past are very strong – King Alfred the Great was born in the town, and there are literary connections to Sir John Betjeman and Thomas Hardy. The historic market town is the gateway to the Ridgeway – an ancient route through downland, secluded valleys and woodland – where you can enjoy magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse, observe its prehistoric hill figure and pass through countless quintessential English country villages. If you are already local to Wantage, we hope you will discover something new. KING ALFRED THE GREAT, BORN IN WANTAGE, 849AD Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com 3 WANTAGE THE NUMBER ONE LOCATION FOR SENIOR LIVING IN WANTAGE Fleur-de-Lis Wantage comprises 32 beautifully appointed one and two bedroom luxury apartments, some with en-suites. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan Website.10

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan 2011-2031 Uffington Parish Council & Baulking Parish Meeting Made Version July 2019 Acknowledgements Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting would like to thank all those who contributed to the creation of this Plan, especially those residents whose bouquets and brickbats have helped the Steering Group formulate the Plan and its policies. In particular the following have made significant contributions: Gillian Butler, Wendy Davies, Hilary Deakin, Ali Haxworth, John-Paul Roche, Neil Wells Funding Groundwork Vale of the White Horse District Council White Horse Show Trust Consultancy Support Bluestone Planning (general SME, Characterisation Study and Health Check) Chameleon (HNA) Lepus (LCS) External Agencies Oxfordshire County Council Vale of the White Horse District Council Natural England Historic England Sport England Uffington Primary School - Chair of Governors P Butt Planning representing Developer - Redcliffe Homes Ltd (Fawler Rd development) P Butt Planning representing Uffington Trading Estate Grassroots Planning representing Developer (Fernham Rd development) R Stewart representing some Uffington land owners Steering Group Members Catherine Aldridge, Ray Avenell, Anna Bendall, Rob Hart (Chairman), Simon Jenkins (Chairman Uffington Parish Council), Fenella Oberman, Mike Oldnall, David Owen-Smith (Chairman Baulking Parish Meeting), Anthony Parsons, Maxine Parsons, Clare Roberts, Tori Russ, Mike Thomas Copyright © Text Uffington Parish Council. Photos © Various Parish residents and Tom Brown’s School Museum. Other images as shown on individual image. Executive Summary This Neighbourhood Plan (the ‘Plan’) was prepared jointly for the Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting. Its key purpose is to define land-use policies for use by the Planning Authority during determination of planning applications and appeals within the designated area. -

Kur Geriau? Vaikams Gali Būti Dar Sunkiau, Jeigu Atsi- Dalyvauja 15 Metų Paaugliai

Sek mūsų naujienas Facebook.com/Info Ekspresas SAVAITRAŠTIS TUVI IE ŠK L A S nemokamas L AI KRAŠTIS 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 FREE LITHUANIAN NEWSPAPER www.ekspresas.co.uk Didžioji Britanija Mokykla Lietuvoje LAPĖ apkandžiojo vaiką ar Anglijoje – kur 2 psl. geriau? Interviu 6-7psl. A.Kaniava - apie teatrą, muziką ir gyvenimą 10-11psl. Laisvalaikis Regent street kalėdinių lempučių įžiebimas 12 psl. www.ekspresas.co.uk Facebook.com/Info Ekspresas Kiekvieną savaitę patogiais autobusais bei mikro autobusais vežame keleivius maršrutais Anglija - Lietuva. Siuntinių pervežimas - nuo durų iki durų. LT: +370 60998811 www.lietuva-anglija-vezame.com Lapkričio mėn. bilietai UK: +44 7845 416024 į/iš Londoną (o) TIK £50 El.p.: [email protected] SAVAITRAŠTIS SAVAITRAŠTIS 2 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 Aktualijos: Didžioji Britanija Aktualijos: Didžioji Britanija 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 3 Parengė Karolina Germanavičiūtė Parengė Karolina Germanavičiūtė Įėjusi į namus lapė apkandžiojo vaiką Tariama, kad voro įkandimas Dvejų metų ber- riksmą. Mamai nubėgus į vaiko kambarį, niukas buvo išvežtas jie pamatė, kad vaiko koja kruvina, o kam- į ligoninę po to, kai bario kampe blaškosi lapė. lapė įėjusi į namus jį Sykį trenkusi gyvūnui, mama jo nesu- nusinešė moters gyvybę apkandžiojo. gavo ir lapė paspruko atgal pro ten iš kur 60-metė Pat Gough-Irwin (liet. Pet Gou- Pietų Londone, atėjusi. Irvin) po voro įkandimo mirė skausmuose New Addington (liet. Mažamečio tėvai su vaiku išskubėjo į ar- ir agonijoje. Prieš daugiau nei metus pas- Naujasis Adingtonas) timiausią „Croydon University“ ligoninę, klidus žiniai apie nuodingus vorus atsiras- gyvenanti šeima na- kur vaiko kulnas buvo sutvarstytas ir susiū- davo vis daugiau pranešimų apie šių vora- muose augina katiną, tas, bei buvo įduotas antibiotikų kursas. -

Architecture, Style and Structure in the Early Iron Age in Central Europe

TOMASZ GRALAK ARCHITECTURE, STYLE AND STRUCTURE IN THE EARLY IRON AGE IN CENTRAL EUROPE Wrocław 2017 Reviewers: prof. dr hab. Danuta Minta-Tworzowska prof. dr hab. Andrzej P. Kowalski Technical preparation and computer layout: Natalia Sawicka Cover design: Tomasz Gralak, Nicole Lenkow Translated by Tomasz Borkowski Proofreading Agnes Kerrigan ISBN 978-83-61416-61-6 DOI 10.23734/22.17.001 Uniwersytet Wrocławski Instytut Archeologii © Copyright by Uniwersytet Wrocławski and author Wrocław 2017 Print run: 150 copies Printing and binding: "I-BIS" Usługi Komputerowe, Wydawnictwo S.C. Andrzej Bieroński, Przemysław Bieroński 50-984 Wrocław, ul. Sztabowa 32 Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER I. THE HALLSTATT PERIOD 1. Construction and metrology in the Hallstatt period in Silesia .......................... 13 2. The koine of geometric ornaments ......................................................................... 49 3. Apollo’s journey to the land of the Hyperboreans ............................................... 61 4. The culture of the Hallstatt period or the great loom and scales ....................... 66 CHAPTER II. THE LA TÈNE PERIOD 1. Paradigms of the La Tène style ................................................................................ 71 2. Antigone and the Tyrannicides – the essence of ideological change ................. 101 3. The widespread nature of La Tène style ................................................................ -

Wiltshire White Horses (Pdf)

Wiltshire’s White Horses The Wiltshire Countryside is famous for its white horse chalk hill figures. It is thought that there have been 13 white horses in existence in Wiltshire, but only 8 are sll visible today. The oldest, largest and perhaps the most well known white horse is carved into the chalk hillside across the border in Oxfordshire. Lile is known of the history of the Uffington White Horse, but it is believed to have influenced the cung of the subsequent Wiltshire horses. The first of the Wiltshire white horses to appear was at Westbury in 878AD, although this figure is no longer visible as a new horse was cut on top in 1778. The most recent horse was cut on the hill above Devizes very near to Team Fredericks to celebrate the Millennium. Westbury: The original Westbury white horse was said to be very different in appearance to the horse that appears today. The earlier horse, if local sketches are to be believed, had short legs and a long heavy body, it wore a saddle and had a tail that pointed upwards. In 1778, Lord Abingdon's steward, a Mr. George Gee took it upon himself to re‐design the Westbury horse and changed the appearance of the landscape for ever more. The old horse was completely lost under this new design, and many branded Gee a Barbarian and vandal. Cherhill: A unique aracon of the Cherhill horse was its eye. Measuring four feet in diameter, Aslop filled the eye with glass boles embedded into the turf face down. -

Coin Inscriptions and the Origins of Writing in Pre-Roman Britain1 Jonathan Williams

COIN INSCRIPTIONS AND THE ORIGINS OF WRITING IN PRE-ROMAN BRITAIN1 JONATHAN WILLIAMS Introduction THE subject of writing in pre-Roman Britain has, until recently, been the object of curious neglect among archaeologists and historians. One simple reason for this is that there is not very much of it in evidence. There are no lapidary inscriptions, and only a few, short graffiti and other scraps of evidence (on which see more below). Contrast this with the situation after the Roman conquest, and the overwhelming impression is that pre-Roman Britain was essentially a pre-literate society, and that writing was brought to Britain by the Romans. And yet there is the not inconsiderable corpus of coin legends from pre-Roman Britain which, if allowed to do so, might seem to tell a rather different story. The object of this paper is to see what kind of story that might be. It has always been a major blind-spot of numismatists, and increasingly archaeologists too since they stopped reading ancient texts, that they tend not to think very much about coin legends other than as a key to attributing the coin to a particular tribe, city or ruler. One result of this is that it seems to have gone more or less unremarked upon in most treatments of late iron-age Britain that the coin legends that appear on the coins in the late first century BC are the first, and by far the largest, body of evidence for the introduction of writing into these islands and of its uses in the pre-Roman period. -

Signposts to Prehistory

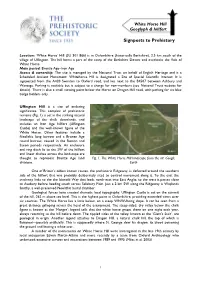

White Horse Hill Geoglyph & hillfort Signposts to Prehistory Location: ‘White Horse’ Hill (SU 301 866) is in Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), 2.5 km south of the village of Uffington. The hill forms a part of the scarp of the Berkshire Downs and overlooks the Vale of White Horse. Main period: Bronze Age–Iron Age Access & ownership: The site is managed by the National Trust on behalf of English Heritage and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Whitehorse Hill is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It is signposted from the A420 Swindon to Oxford road, and lies next to the B4507 between Ashbury and Wantage. Parking is available but is subject to a charge for non-members (see National Trust website for details). There is also a small viewing point below the Horse on Dragon Hill road, with parking for six blue badge holders only. Uffington Hill is a site of enduring significance. This complex of prehistoric remains (Fig. 1) is set in the striking natural landscape of the chalk downlands, and includes an Iron Age hillfort (Uffington Castle) and the well-known figure of the White Horse. Other features include a Neolithic long barrow and a Bronze Age round barrow, reused in the Roman and Saxon periods respectively. An enclosure and ring ditch lie to the SW of the hillfort and linear ditches across the landscape are thought to represent Bronze Age land Fig. 1. The White Horse Hill landscape from the air. Google divisions. Earth One of Britain’s oldest known routes, the prehistoric Ridgeway, is deflected around the southern side of the hillfort that was probably deliberately sited to control movement along it. -

Celtic Coins and Their Archetypes

Celtic Coins and their Archetypes The Celts dominated vast parts of Europe from the beginning of the 5th century BC. On their campaigns they clashed with the Etruscans, the Romans and the Greeks, they fought as mercenaries under Philip II and Alexander the Great. On their campaigns the Celts encountered many exotic things – coins, for instance. From the beginning of the 3rd century, the Celts started to strike their own coins Initially, their issued were copies of Greek, Roman and other money. Soon, however, the Celts started to modify the Greek and Roman designs according to their own taste and fashion. By sheer abstraction they managed to transform foreign models into typically Celtic artworks, which are often almost modern looking. 1 von 27 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC) in the Name of Philip II, Stater, c. 324 BC, Colophon Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Colophon Year of Issue: -324 Weight (g): 8.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation Through decades of warfare, King Philip II had turned Macedon into the leading power of the Greek world. In the summer of 336 BC he was assassinated, however, and succeeded by his son Alexander, who would later be known as "the Great." This coin was minted one year before Alexander's death. It bears a beautiful image of Apollo. The coin is a so-called Philip's stater, as Alexander's father Philip had already issued them for diplomatic purposes (bribery thus) and for the pay of his mercenaries.