14630198441.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habaneros from My Backyard Garden Infused This Vodka with a Glassy Golden Hue

More Edge Than Edgy by Barbara Haas appeared in The Isthmus Review, 2019 Habaneros from my backyard garden infused this vodka with a glassy golden hue. I angled the bottle toward the window, tilting it just-so. Plenty of sunshine streamed through. I had whipped this batch up from Belaya Berezka, a premium brand I had brought back from Moscow last month. My homespun recipe called for a ratio of three habaneros to one liter. When I sliced the peppers, a vapor wave of pungent heat wafted up and engulfed me. I even recoiled somewhat, because the skin around my nose suddenly tingled. The peppers were richly pigmented inside and out—zesty, orange and bright—and my knife left bold fiery streaks on the cutting board. On the day I sieved the vodka and filtered it through a fine mesh cloth, nothing about the spent slices or seeds said “habanero” any longer. Three weeks in a cool dark place allowed Scoville Units to transfer massively to the vodka. A 40% alcohol content had performed a Total Takedown on the habaneros. The exchange between the two had been supreme. When I flew back from Moscow last month, this liter of Belaya Berezka was crystalline and clear. It had now acquired a striking amber glow but remained as transparent as glass. I stood the bottle in the freezer all afternoon and then later that evening downed a shot “in one,” as my Muscovite komradski might say. Cold and spicy at the same time, this vodka would torch a Bloody Mary to perfection. -

Please Download Issue 2 2012 Here

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. June 2012. Vol. V:2. 1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Academic life in newly Södertörn University, Stockholm founded Baltic States BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com LANGUAGE &GYÖR LITERATUREGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG GYÖRGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG also in this issue ILL. LARS RODVALDR SIBERIA-EXILES / SOUNDPOETRY / SREBRENICA / HISTORY-WRITING IN BULGARIA / HOMOSEXUAL RIGHTS / RUSSIAN ORPHANAGES articles2 editors’ column Person, myth, and memory. Turbulence The making of Raoul Wallenberg and normality IN auGusT, the 100-year anniversary of seek to explain what it The European spring of Raoul Wallenberg’s birth will be celebrated. is that makes someone 2012 has been turbulent The man with the mission of protect- ready to face extraordinary and far from “normal”, at ing the persecuted Jewish population in challenges; the culture- least when it comes to Hungary in final phases of World War II has theoretical analyzes of certain Western Euro- become one of the most famous Swedes myth, monuments, and pean exemplary states, of the 20th century. There seem to have heroes – here, the use of affected as they are by debt been two decisive factors in Wallenberg’s history and the need for crises, currency concerns, astonishing fame, and both came into play moral exemplars become extraordinary political around the same time, towards the end of themselves the core of the solutions, and growing the 1970s. The Holocaust had suddenly analysis. public support for extremist become the focus of interest for the mass Finally: the historical political parties. -

Approved Alcoholic Brands 2012-2013

Approved Brands for: 2012/2013 Last Updated: 5/13/2013 * List is grouped based on Brand Type then sorted by Brand name in alphabetical order. Type: D = Distilled Spirits, W = Wines Nashville Knoxville Memphis Chattanooga TypeBrand Name Registrant Area Area Area Area D (ri)1 - Whiskey Jim Beam Brands Co. HORIZON-NASH B&T ATHENS-MEMP HORIZON-CHAT D 10 Cane - Rum Moet Hennessy USA, Inc. HORIZON-NASH TRIPLE C WEST TN CROW HORIZON-CHAT D 100 Anos - Tequila Jim Beam Brands Co. HORIZON-NASH TRIPLE C WEST TN CROW HORIZON-CHAT D 100 Pipers - Whiskey Heaven Hill Distilleries, Inc. LIPMAN KNOX BEVERAGE WEST TN CROW ATHENS-CHAT D 12 Ouzo - Cordials & Liqueurs Skyy Spirits, LLC HORIZON-NASH KNOX BEVERAGE WEST TN CROW HORIZON-CHAT D 13th Colony Southern - Gin Thirteenth Colony Distilleries, LLC HORIZON-CHAT D 13th Colony Southern - Neutral Spirits or Al Thirteenth Colony Distilleries, LLC HORIZON-CHAT D 1776 Bourbon - Whiskey Georgetown Trading Company, LLC HORIZON-NASH HORIZON-CHAT D 1776 Rye - Whiskey Georgetown Trading Company, LLC HORIZON-NASH KNOX BEVERAGE HORIZON-CHAT D 1800 - Flavored Distilled Spirits Proximo Spirits LIPMAN BEV CONTROL ROBILIO HORIZON-CHAT D 1800 - Tequila Proximo Spirits LIPMAN BEV CONTROL ROBILIO HORIZON-CHAT D 1800 Coleccion - Tequila Proximo Spirits LIPMAN BEV CONTROL ROBILIO HORIZON-CHAT D 1800 Ultimate Margarita - Flavored Distilled Proximo Spirits LIPMAN BEV CONTROL ROBILIO HORIZON-CHAT D 1816 Cask - Whiskey Chattanooga Whiskey Company, LLC ATHENS-NASH B&T ATHENS-MEMP ATHENS-CHAT D 1816 Reserve - Whiskey Chattanooga Whiskey Company, LLC ATHENS-NASH B&T ATHENS-MEMP ATHENS-CHAT D 1921 - Tequila MHW, Ltd. -

Sindbad and Maritales Bar Menu FOR

Rum* WHITE Bacardi 300 DARK Captain Morgan Black Label 300 FLAVOURED Malibu 300 DOMESTIC Old Cask 250 Old Monk Gold 250 Some Beverages or particular brands may not always be available, We appologize for the inconvenience. 58% VAT and 6% Service Tax is included on imported liquor and wine. 14.5% VAT and the 6% Service Tax is applicable on domestic liquor. Your bill attracts a discretionary Service Charge of 5% on Food & Beverage service. *Standard measure for spirits is 30 ml. **Standard measure 45 ml. ^Standard measure 60 ml. ^^Standard measure 90 ml. Brandy* IMPORTED COGNAC XO Remy Martin 2000 Hennessy 2000 Martel Xo 2000 VS Hennessy VS 675 VSOP Remy Martin 675 Courvoisier 600 Martel 600 DOMESTIC VSOP Deluxe 250 McDowell's Premium 175 250 Morpheus XO 300 Some Beverages or particular brands may not always be available, We appologize for the inconvenience. 58% VAT and 6% Service Tax is included on imported liquor and wine. 14.5% VAT and the 6% Service Tax is applicable on domestic liquor. Your bill attracts a discretionary Service Charge of 5% on Food & Beverage service. *Standard measure for spirits is 30 ml. **Standard measure 45 ml. ^Standard measure 60 ml. ^^Standard measure 90 ml. Vodka* INTERNATIONAL Absolut ELYX 500 Belvedere 500 Grey Goose 500 Ciroc 400 Ketel One 300 Stolichnaya 300 Absolut Blue 350 Absolut Citron 350 Absolut Mandarin 350 Absolut Pepper 350 Absolut Raspberry 350 Absolut Kurant 350 Smirnoff 350 DOMESTIC Romanov 250 Eristoff 250 Some Beverages or particular brands may not always be available, We appologize for the inconvenience. -

Mrp Poster for All Brands

TAMIL NADU STATE MARKETING CORPORATION LIMITED MRP PRICE LIST w.e.f.13.10.2017 MAXIMUM RETAIL PRICE OF IMFS BRANDS SL. NAME OF THE COMPANY / BRAND Range M.R.P. SL. NAME OF THE COMPANY / BRAND Range M.R.P. No. 1000 ml 750 ml 375 ml 180 ml No. 1000 ml 750 ml 375 ml 180 ml M/S. ENRICA ENTERPRISES PVT. LTD. Rs. Rs. Rs. Rs. M/S. S A F I L Rs. Rs. Rs. Rs. 1 GOLDEN GRAPE ORDINARY BRANDY O 400 200 100 1 DIAMOND BRANDY O 400 200 100 2 OLD KING XXXX RUM O 400 200 100 2 DIAMOND WHISKY O 400 200 100 3 MEN'S CLUB DELUXE BRANDY O 400 200 100 3 DIAMOND XXX RUM O 400 200 100 4 HONEY BEE MEDIUM BRANDY M 440 220 110 4 SAFL SUPER STAR BDY O 400 200 100 5 NO.1 MC DOWELL MEDIUM BRANDY M 440 220 110 5 SAFL SUPER STAR WHY O 400 200 100 6 BAGPIPER MEDIUM WHISKY M 440 220 110 6 SAFL SUPER STAR XXX RUM O 400 200 100 7 NO.1 MC DOWELL MEDIUM WHISKY M 440 220 110 7 DIAMOND ORDINARY GIN O 400 200 100 MCDOWELL CELEBRATION PREMIUM 8 RUM P 520 260 130 8 MGM MEDIUM VODKA M 440 220 110 9 MCDOWELL'S GREEN LABEL WHISKY P 520 260 130 9 MGM ORANGE MEDIUM VODKA M 440 220 110 10 MCDOWELL'S VSOP BRANDY P 520 260 130 10 MGM APPLE MEDIUM VODKA M 440 220 110 11 MCDOWELL'S CENTURY WHISKY P 560 280 140 11 MGM WHITE MEDIUM RUM M 440 220 110 12 VSOP EXSHAW GOLD BRANDY P 600 300 150 12 MGM NO.1 VSOP BRANDY M 440 220 110 P SPECIAL APPOINTMENT DELUXE 13 CAESAR PREMIUM BRANDY 600 300 150 13 BRANDY P 520 260 130 P MGM RICHMAN'S DELUXE XXX 14 SIGNATURE RARE PREMIUM WHISKY 1010 760 380 190 14 RUM P 520 260 130 MGM RICHMAN'S NO.1 GRAPE 15 ROYAL CHALLENGE DELUXE WHISKY P 1010 760 380 190 15 BRANDY P 560 280 140 LOUIS VERNANT XO BLENDED PREMIUM MAGIC MOMENTS PREMIUM GRAIN 16 BRANDY P 800 400 200 16 VODKA P 640 320 160 ANTIQUITY BLUE SUPER PREMIUM MGM GOLD VSOP PREMIUM 17 WHISKY P 1120 560 280 17 BRANDY P 850 640 320 160 MGM INDIAN CHALLENGE 18 PREMIUM WHISKY P 760 380 190 CLOVIS XO FRENCH GRAPE 19 BRANDY P 840 420 210 M/S. -

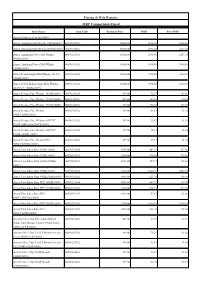

Pricing & Web Reports MRP Comparision Report

Pricing & Web Reports MRP Comparision Report Item Name Item Code Declared Price MRP Prev.MRP Amrut Distilleries Pvt Ltd (0009) Amrut Amalgam Malt Whisky 750ML(0009) 00090102901 15000.00 3894.68 3400.86 Amrut Amalgam Malt Whisky-500ML(0009) 00090102916 15000.00 2596.45 2267.24 Amrut Amalgam Peated Malt Whisky 00090103116 15000.00 2596.45 2267.24 500ML(0009) Amrut Amalgam Peated Malt Whisky 00090103101 15000.00 3894.68 3400.86 750ML(0009) Amrut Fusion Single Malt Whisky (42.8%) 00090103201 15000.00 3894.68 3400.86 750ML(0009) Amrut Peated Indian Single Malt Whisky- 00090103301 15000.00 3894.68 3400.86 42.8%V/V 750ML(0009) Amrut Prestige Fine Whisky 180 Ml (0009) 00090100304 499.00 70.27 63.10 Amrut Prestige Fine Whisky 375 Ml (0009) 00090100302 499.00 145.43 130.49 Amrut Prestige Fine Whisky 750 Ml (0009) 00090100301 499.00 290.85 260.98 Amrut Prestige Fine Whisky 00090100352 499.00 35.13 31.55 90MLx96Btls(0009) Amrut Prestige Fine Whisky-ASEPTIC 00090190352 499.00 35.13 31.55 PACK 90MLx96A PACK(0009) Amrut Prestige Fine Whisky-ASEPTIC 00090190304 499.00 70.27 63.10 PACK-180ML (0009) Amrut Prestige Fine Whisky-PET 00090102652 499.00 35.13 31.55 90MLx96P.Btls (0009) Amrut Two Indies Rum 180ML(0009) 00090301104 4554.00 467.51 397.00 Amrut Two Indies Rum 375ML(0009) 00090301102 3800.00 930.47 783.56 Amrut Two Indies Rum 60MLx150Btls 00090301107 4924.00 157.17 133.66 (0009) Amrut Two Indies Rum 750ML(0009) 00090301101 3800.00 1860.94 1567.14 Amrut Two Indies Rum 90MLx96Btls(0009) 00090301152 4554.00 233.76 198.50 Amrut Two Indies Rum-PET 180ML(0009) -

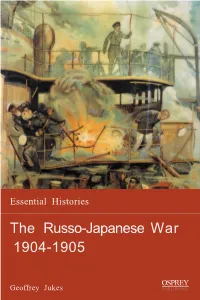

Essential Histories

Essential Histories The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905 OSPREY Geoffrey Jukes PUBLISHING After leaving Oxford in 1953 GEOFFREY JUKES spent 14 years in the UK Ministry of Defence and Foreign and Colonial Office, specialising in Russian/Soviet military history, strategy and arms control. From 1967 to 1993 he was also on the staff of the Australian National University. He has written five books and numerous articles on the Eastern Front in the two World Wars. PROFESSOR ROBERT O'NEILL, AO D.PHIL. (Oxon), Hon D. Litt.(ANU), FASSA, Fr Hist S, is the Series Editor of the Essential Histories. His wealth of knowledge and expertise shapes the series content and provides up-to-the-minute research and theory. Born in 1936 an Australian citizen, he served in the Australian army (1955-68) and has held a number of eminent positions in history circles, including the Chichele Professorship of the History of War at All Souls College, University of Oxford, 1987-2001, and the Chairmanship of the Board of the Imperial War Museum and the Council of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London. He is the author of many books including works on the German Army and the Nazi party, and the Korean and Vietnam wars. Now based in Australia on his retirement from Oxford he is the Chairman of the Council of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Essential Histories The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905 Essential Histories The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905 OSPREY Geoffrey Jukes PUBLISHING First published in Great Britain in 2002 by Osprey Publishing, For a complete list of titles available from Osprey Publishing Elms Court, Chapel Way, Botley, Oxford, OX2 9LR please contact: Email: [email protected] Osprey Direct UK, PO Box 140, © 2002 Osprey Publishing Limited Wellingborough, Northants, NN8 2FA, UK. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Paul Kulikovsky №83 February 2015 Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich - Portrait by Konstantin Gorbunov, 2015 In memory of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich It was quite amazing how many events was held this year in commemoration of the assassination of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich - 110 years ago - on 17th of February 1905. Ludmila and I went to the main event, which was held in Novospassky Monastery, were after the Divine liturgy, was held a memorial service for Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, who is buried there in the crypt of the Romanov Boyars. The service in the church of St. Romanos the melodist (in the crypt of the Romanov Boyars) was led by Bishop Sava and Bishop Photios Nyaganskaya Ugra and concelebrated by clergy of Moscow. The service was attended by Presidential Envoy to the Central Federal District A.D. Beglov, Chairman of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society S.V. Stepashin, chairman of the Moscow City Duma A.V. Shaposhnikov, President of Elisabeth Sergius Educational Society Anna V. Gromova, Grand Duke George Michailovich and Olga Nicholaievna Kulikovsky-Romanoff, Ludmila and Paul Kulikovsky, Director of Russian State Archives S. V. Mironenko, and members of the Russian Nobility Assembly. Present were also the icon of Mother of God "Quick to Hearken" to which members of the Romanov family were praying, and later residents of besieged Leningrad. It had arrived a few days earlier from the Holy Trinity Cathedral in Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg. The Mother of God is depicted on it without the baby, praying with outstretched right hand. -

Millionaires' Club

THE DEFINITIVE RANKING OF THE WORLD'S MILLION-CASE SPIRITS BRANDS 2014 TPSSPVUHPYLThe Z» The TPSSPVUHPYLZ» JUNE 2014 DRINKSINT.COM 3 GRAND DESIGNS t was once a case of the worldly and the parochial – the global brands and the local brands. But what happens when local goes international, when low- value operators premiumise? In The Millionaires’ IClub 2014, we have learned of such grand plans. Take our immovable champion, Jinro. Far from content with 66.5m case sales concentrated in South Korea and nearby Japan, Hite-Jinro has set about achieving 100m cases in the next 10 years, by seeding the brand in the 11 world markets with a population of more than 100m. That includes the US – a market now inhabited by Philippine rum Tanduay and the world’s latest largest whisky brand, Officer’s Choice, which has entered New York. In the west there is a tendency to think the flow of globalisation only works in one direction, from traditional to emerging markets. But the growth obsession is an instinct of business, not the preserve of the elite. Spirits companies propagated in volatile emerging markets are all too aware that a one-market policy can build volumes but not a secure future. Market plurality is the best way to mitigate exposure. Johnnie Walker is the exemplar. With Asia ailing in 2013, the brand’s worldwide distribution kept sales walking in the right direction. Of course, emerging brands will have to climb the premium ladder quickly if they are to take on Johnnie contents Walker’s ilk in the likes of the US and western Europe. -

Gurdaspur Punjab Kings Whisky 180 35 2 Ab Grains Spirits Pvt

Sr. No. WHOLESALE_VEND_NAME BRAND_NAME SIZE_CODE MRP 1 AB GRAINS SPIRITS PVT. LTD. - GURDASPUR PUNJAB KINGS WHISKY 180 35 2 AB GRAINS SPIRITS PVT. LTD. - GURDASPUR PUNJAB KINGS WHISKY 375 65 3 AB GRAINS SPIRITS PVT. LTD. - GURDASPUR PUNJAB KINGS WHISKY 750 130 4 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI AUBERGE PREMIUM VODKA GR APPLE 180 100 5 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI AUBERGE PREMIUM VODKA GR APPLE 375 200 6 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI AUBERGE PREMIUM VODKA GR APPLE 750 400 7 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGGLER BL SCOTCH WHISKY 750 1050 8 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGL. XXX MATURED RUM 180 60 9 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGL. XXX MATURED RUM 375 120 10 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGL. XXX MATURED RUM 750 240 11 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI WHITE & BLUE PREMIUM WHISKY 180 100 12 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI WHITE & BLUE PREMIUM WHISKY 375 205 13 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI WHITE & BLUE PREMIUM WHISKY 750 410 14 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA GREEN APPLE 180 145 15 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA GREEN APPLE 750 580 16 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA ORANGE 180 145 17 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA ORANGE 750 580 18 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 60 45 19 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 90 70 20 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 180 135 21 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 375 275 22 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 750 550 23 A-ONE WINERIES - SANGRUR ORIGINAL CH RARE DEL WHISKY 180 50 24 A-ONE WINERIES - SANGRUR ORIGINAL CH RARE DEL WHISKY 375 100 25 A-ONE WINERIES - SANGRUR ORIGINAL CH RARE DEL WHISKY 750 200 26 BACARDI INDIA PRIVATE LTD. -

The Millionaires' Club

The definiTive ranking of The world's million-case spiriTs brands June 2012 The definiTive ranking of The world's million-case spiriTs brands 2012 The The June 2012 drinksint.com 3 welcome to the club here are clubs for ladies, for gentlemen, the gentry and the socially sedentary. Clubs where handshakes, back-slaps and ridiculous blazers Tmaintain a cosy elitism. The Millionaires’ Club is not one of these clubs. Here we favour meritocracy over cronyism – if a spirits or liqueur brand sells a million 9-litre cases it’s in, if it doesn’t, it’s out. This year the revolving door has welcomed more brands than it has ejected, with membership now numbering 181. We have a slew of novice Millionaires – affirmation to burgeoning brands that if you get the proposition and market right, the million-case mark is eminently achievable. contents Of the newcomers to Millionaire status there’s La leADer voDkA Martiniquaise’s Poliakov vodka, which inched its way past the Hamish Smith plays secretary 3 Lowdown on Europe’s favourite 23 million-case mark, presumably in the very last knockings of 2011. Then you have Cîroc which, through P Diddy’s notoriety mArket overvIew rum & cAchAçA and Diageo’s know-how, managed to pole-vault nearly 50 of its By Euromonitor International 5 Latin America’s heavyweights 29 competitors to debut at 133. The global analysts at Euromonitor International have also Full lIStIng cognAc & brAnDy unearthed some new names. There are those that have quietly All 181 Millionaire brands 9 The little and large grape spirits 30 amassed sales but been shy up to now about opening their ledgers. -

Indian Liquor S.No Category Brand Name Size

Indian Liquor Size MRP(in Rs) S.No Category Brand Name (in ml) w.e.f 18/06/2014 1 Alcopop BACARDI + LEMONADE 275 85 2 Alcopop BACARDI RAZZ UP 275 85 3 Alcopop BREEZER CRANBERRY 275 60 4 Alcopop BREEZER LIME 275 60 5 Alcopop BREEZER ORANGE 275 60 6 Alcopop BREEZER PR BL.BERRY CRUSH 275 85 7 Alcopop BREEZER PR. TROPICAL LIME 275 85 8 Alcopop BREEZER PR. TROPICAL OR. 275 85 9 Alcopop BREEZER PR.JAMAICAN PASON 275 85 10 Alcopop BREEZER PR.TROPICAL C.BERY 275 85 11 Alcopop FLIP FUNK BLACK BERRY 275 80 12 Alcopop FLIP FUNK BLUE BERRY 275 80 13 Alcopop FLIP FUNK CRANBERRY 275 80 14 Alcopop FLIP FUNK GREEN APPLE 275 80 15 Alcopop FLIP FUNK LEMON 275 80 16 Alcopop FLIP FUNK LYCHEE 275 80 17 Alcopop FLIP FUNK MANGO 275 80 18 Alcopop FLIP FUNK ORANGE 275 80 19 Alcopop FLIP FUNK PASSION FRUIT 275 80 20 Alcopop FLIP FUNK WATER MELON 275 80 21 Beer BUDWEISER MAGNUM STRONG BEER 330 80 22 Beer BUDWEISER MAGNUM STRONG BEER 500 120 23 Beer BUDWEISER MAGNUM STRONG BEER 650 155 24 Beer BUDWEISER PR KING OF BEERS 330 70 25 Beer BUDWEISER PR KING OF BEERS 330 65 26 Beer BUDWEISER PR KING OF BEERS 500 95 27 Beer BUDWEISER PR KING OF BEERS 650 120 28 Beer CALS CHILL ALL MALT PR. BEER 330 65 29 Beer CALS CHILL ALL MALT PR. BEER 500 100 30 Beer CALS CHILL ALL MALT PR. BEER 650 125 31 Beer CALS ELEPHANT S.S PR BEER 330 60 32 Beer CALS ELEPHANT S.S PR BEER 500 90 33 Beer CALS ELEPHANT S.S PR BEER 650 115 34 Beer COX 10000 S.S.