Terrorist Threats: Dreaming Beyond the Violence of Anti-Muslim Racism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Absolute Lyrics (n.d.) ‘Galang – M.I.A.’, accessed 25 October 2012, absolutelyrics.com/lyrics/view/m.i.a./ galang/. Anderson, Jon Lee (2011) ‘Death of the Tiger’, The New Yorker, 17 January, accessed 3 March 2014. newyorker. com/magazine/2011/01/17/death-of-the-tiger/. Anderson, Sean and Jennifer Ferng (2013) ‘No Boat: The Architecture of Christmas Island’ Architectural Theory Review 18.2: 212–226. Appadurai, Arjun (1993) ‘Number in the Colonial Imagination’, in C.A. Breckenridge & P. van der Veer, eds. Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press) 314–39. _______. (2003) ‘Disjuncture and Difference in a Global Economy’ in Jana Evans Braziel & Anita Mannur, eds. Theorizing Diaspora (London: Blackwell) 25–48. Arasanayagam, Jean (2009) ‘Rendition’, Sunday Times (Sri Lanka) August 3 2008, accessed 20 January 2010 http://www.sundaytimes.lk/080803/Plus/ sundaytimesplus_01.html. Arulpragasam, Mathangi Maya (2012) M.I.A. (New York: Rizzoli). Auden, W.H. (1976) Collected Poems. Edited by E. Mendelson (London: Faber & Faber). Australian (2007) ‘Reaching for Dog Whistle and Stick’, editorial, 2 August. Balasingham, Adele Ann (1993) Women Fighters of Liberation Tigers (Jaffna: LTTE). DOI: 10.1057/9781137444646.0014 Bibliography Balint, Ruth (2005) Troubled Waters (Sydney: Allen & Unwin). Bastians, Dharisha (2015) ‘In Gesture to Tamils, Sri Lanka Replaces Provincial Leader’, New York Times, 15 January, http://www. nytimes.com/2015/01/16/world/asia/new-sri-lankan-leader- replaces-governor-of-tamil-stronghold.html?smprod=nytcore- ipad&smid=nytcore-ipad-share&_r=0. Bavinck, Ben (2011) Of Tamils and Tigers: A Journey Through Sri Lanka’s War Years (Colombo: Vijita Yapa and Rajini Thiranagama Memorial Committee). -

Borderlands E-Journal

borderlands e-journal www.borderlands.net.au VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1, 2012 Missing In Action By all media necessary Suvendrini Perera School of Media, Culture & Creative Arts, Curtin University This essay weaves itself around the figure of the hip-hop artist M.I.A. Its driving questions are about the impossible choices and willed identifications of a dirty war and the forms of media, cultural politics and creativity they engender; their inescapable traces and unaccountable hauntings and returns in diasporic lives. In particular, the essay focuses on M.I.A.’s practice of an embodied poetics that expresses the contradictory affective and political investments, shifting positionalities and conflicting solidarities of diaspora lives enmeshed in war. In 2009, as the military war in Sri Lanka was nearing its grim conclusion, with what we now know was the cold-blooded killing of thousands of Tamil civilians inside an official no-fire zone, entrapped between two forms of deadly violence, a report in the New York Times described Mathangi ‘Maya’ Arulpragasam as the ‘most famous member of the Tamil diaspora’ (Mackey 2009). Mathangi Arulpragasam had become familiar to millions across the globe in her persona as the hip-hop performer M.I.A., for Missing in Action. In the last weeks of the war, she made a number of public appeals on behalf of those trapped by the fighting, including a last-minute tweet to Oprah Winfrey to save the Tamils. Her appeal, which went unheeded, was ill- judged and inspired in equal parts. It suggests the uncertain, precarious terrain that M.I.A. -

Professors to Discuss War Issues

NONPROFIT ORGANIZATION WITH NINE QUARTERBACKS, THERE WILL BE A FIGHT TO START PAGE 4 U.S. POSTAGE BATTLE FOR THE BALL: PAID BAYLOR UNIVERSITY ROUNDING UP CAMPUS NEWS SINCE 1900 THE BAYLOR LARIAT FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2008 Professors Keston to discuss Institute war issues unveils An open dialogue led by Baylor religious alum and Dr. Ellis to talk about Christian perspectives abuse By Stephen Jablonski Reporter A collection of When Dr. Marc Ellis, director of the Center communist memorabilia for Jewish Studies and universtiy professor, put on display in mentioned a lack of discussion on the moral dilemma of war in Christianity last semester, Carroll Library the notion rang true with Baylor alumnus Adam Urrutia. This proposal culminated a presentation and discussion of topics relevant By Anita Pere to Christians in a world at war. Staff writer Baylor professors will discuss “Being Chris- tian in a Nation at War … What Are We to Say?” Oppression resonates at 3:30 p.m. Feb. 12 in the Heschel Room of through history as a bruise on the Marrs McLean Science Building. Co-spon- the face of humanity. sored by the Center for Jewish Studies and Many of the world’s citi- the Institute for Faith and Learning, the event zens, grappling with constantly was first conceived by Urrutia, who, Ellis said, changing political regimes and took the initiative to organize the discussion. civil unrest, have never known “This issue is particularly close to what I’m civil liberties. interested in,” Urrutia said. “I’m personally a But one cornerstone of all pacifist and I thought this would be a good societies has survived the test opportunity to discuss this with people.” Associated Press of oppression: religion. -

Sound Matters: Postcolonial Critique for a Viral Age

Philosophische Fakultät Lars Eckstein Sound matters: postcolonial critique for a viral age Suggested citation referring to the original publication: Atlantic studies 13 (2016) 4, pp. 445–456 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2016.1216222 ISSN (online) 1740-4649 ISBN (print) 1478-8810 Postprint archived at the Institutional Repository of the Potsdam University in: Postprints der Universität Potsdam Philosophische Reihe ; 119 ISSN 1866-8380 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-98393 ATLANTIC STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 13, NO. 4, 445–456 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2016.1216222 Sound matters: postcolonial critique for a viral age Lars Eckstein Department of English and American Studies, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This essay proposes a reorientation in postcolonial studies that takes Sound; M.I.A.; Galang; music; account of the transcultural realities of the viral twenty-first century. postcolonial critique; This reorientation entails close attention to actual performances, transculturality; pirate their specific medial embeddedness, and their entanglement in modernity; Great Britain; South Asian diaspora concrete formal or informal material conditions. It suggests that rather than a focus on print and writing favoured by theories in the wake of the linguistic turn, performed lyrics and sounds may be better suited to guide the conceptual work. Accordingly, the essay chooses a classic of early twentieth-century digital music – M.I.A.’s 2003/2005 single “Galang”–as its guiding example. It ultimately leads up to a reflection on what Ravi Sundaram coined as “pirate modernity,” which challenges us to rethink notions of artistic authorship and authority, hegemony and subversion, culture and theory in the postcolonial world of today. -

Being Heard Being Heard Being Me Freedom

beingbeing heardheard•• being me•• freedom dignity••power words that burn A resource• •to wordsenable young peoplethat to burn explore human rights and self-expression through poetry. ‘ Poetry is thoughts that breathe and words that burn.’ THOMAS GRAY Introduction Poetry and spoken word are powerful ways to understand and respond to the world, to voice thoughts and ideas, to reach into ourselves and reach out. ‘Josephine Hart described Human rights belong to all of us but are frequently denied or abused even poetry as a route map through in the UK. Poets are often the first to articulate this in a way to make us life. She said “Without think and to inspire action. Perhaps this explains why they’re often among the first to be silenced by oppressive regimes. poetry, life would have Amnesty International is the world’s largest human rights organisation been less bearable, less with seven million supporters. We’ve produced this resource to enable comprehensible and infinitely young people to explore human rights through poetry whilst developing their voice and skills as poets. less enjoyable”. It would be The resource was inspired by the poetry anthology Words that Burn her sincere wish that this curated by Josephine Hart of The Poetry Hour, which in turn was inspired by Amnesty resource will prove the words of Thomas Gray (cover). The essence of these words shaped this to be first steps on a happier resource, which aims to provide the creative oxygen to give young people the confidence to express themselves through poetry, to stand up and make journey through life for many. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

MIA Matangi Mp3, Flac

M.I.A. Matangi mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Rock Album: Matangi Country: UK Released: 2013 Style: Electroclash MP3 version RAR size: 1750 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1155 mb WMA version RAR size: 1983 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 637 Other Formats: WMA VQF RA ADX FLAC AU MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits Karmageddon Engineer – Neil ComberMastered By – Geoff PescheMixed By – M.I.A. , Neil 1 1:34 ComberProducer – M.I.A. , Doc McKinney*, Switch Written-By – Dave Taylor, Martin "Doc" McKinney*, Maya Arulpragasam, Sugu Arulpragasam Matangi 2 Engineer – Neil ComberMastered By – Geoff PescheMixed By – Neil Comber, Switch 5:12 Producer – Switch Written-By – Dave Taylor, Maya Arulpragasam Only 1 U Engineer – Neil ComberMastered By – Geoff PescheMixed By – Surkin, Switch Producer – 3 3:12 M.I.A. , So Japan, Surkin, Switch Written-By – Dave Taylor, Kyle Edwards, Maya Arulpragasam Warriors 4 Engineer – Haze BangaMastered By – Mazen MuradMixed By – Hit-Boy, M.I.A. Producer – 3:41 Hit-Boy, K. Roosevelt*Written-By – Chauncey Hollis, Maya Arulpragasam Come Walk With Me 5 Engineer, Guitar, Mixed By – Neil ComberMastered By – Geoff PescheMixed By – Switch 4:43 Producer – M.I.A. , Switch Written-By – Dave Taylor, Maya Arulpragasam aTENTion 6 Engineer – Neil ComberMastered By – Mazen MuradMixed By – M.I.A. , Switch Producer – 3:40 Switch Written-By – Dave Taylor, Maya Arulpragasam Exodus Engineer – Neil ComberFeaturing – The WeekndMastered By – Geoff PescheMixed By – 7 5:08 M.I.A. , Switch Producer – Illangelo, M.I.A. , Doc McKinney*, The WeekndWritten-By – Abel Tesfaye, C. Montagnese*, Martin "Doc" McKinney*, Maya Arulpragasam Bad Girls Engineer – Marcella "Incredible Lago" Araica*Mastered By – Geoff PescheMixed By – 8 3:47 Marcella "Ms. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2015 T 09

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2015 T 09 Stand: 23. September 2015 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2015 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT09_2015-6 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie sche Katalogisierung von Ausgaben musikalischer Wer- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ke (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

PRESSEHEFT Kinostart

PRESSEHEFT Kinostart: 22. November 2018 Im Verleih von Rapid Eye Movies INHALT Credits / Filmdaten ....................................................................................................................... 3 Synopsis ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Bio-/Filmografie Regie .................................................................................................................. 4 Über die Produktion und die besondere Beziehung zwischen M.I.A. und Steve Loveridge ........ 5 Über das Team .............................................................................................................................. 9 Songliste des Films ........................................................................................................................ 9 Pressestimmen ........................................................................................................................... 15 Kontakte ..................................................................................................................................... 16 2 MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. Ein Film von Steve Loveridge CREDITS Regie & Produktion: Steve Loveridge Mit: Maya Arulpragasam Kamera: Graham Boonzaaier, Catherine Goldsmith, Matt Wainwright Schnitt: Marina Katz, Gabriel Rhodes Musik: Dhani Harrison, Paul Hicks Music Supervisor: Tracy McKnight Sound Design: Ron Bochar Produzenten: Lori Cheatle, Andrew Goldman, Paul Mezey Ausführende Produzenten: -

Students Shun ‘Sexist’ Show

fb.com/warwickboar twitter.com/warwickboar theStudentboar Publication of the Year 2013 Wednesday 4th December, 2013 Est. 1973 | Volume 36 | Issue 5 Without a The perfect Student paddle (or shirt) curry formula theatre deals p. 10 p. 29 p. 30 TV page 27 MONEY page 15 BOOKS page 16 TRAVEL page 24 Doctor Who: an overseas view Writing competition winners The best Christmas reads Where to visit over the holidays Typhoon Haiyan student support Students shun ‘sexist’ show Derin Odueyungbo The University of Warwick has responded to Typhoon Haiyan, which struck the Philippines on Friday 8 November and then north Vietnam on Monday 11 No- vember. Warwick has said that it will “commit itself to proving a sup- portive and positive environment” for those who have been affected by the disaster. There are a number of ways stu- dents can donate towards support- ing people in the Philippines. Students and staff directly af- fected by the recent disaster are en- couraged to take advantage of the University’s support services. Warwick society Oxfam Out- reach held bucket collections in the Bread Oven and Curiositea last week. Unicef on Campus were at Un- plucked in the Dirty Duck on » Kasbah Nightclub, previously known as the Colly, is a favourite with many students at Warwick University. Photo: Localjapantimes / Flickr Tuesday 26 November, collecting donations for those affected by the undergraduate, member of the made the girls and the boys do was “After receiving complaints, he typhoon. Ann Yip campaign and member of the War- laughable.” has now parted ways with the Kas- Mrin Chatterjee, president of wick Anti-Sexism Society (WASS). -

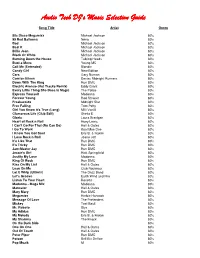

MP3 Database.Wdb

Audio Tech DJ's Music Selection Guide Song Title Artist Genre 80s Disco Megamixx Michael Jackson 80's 99 Red Balloons Nena 80's Bad Michael Jackson 80's Beat It Michael Jackson 80's Billie Jean Michael Jackson 80's Black Or White Michael Jackson 80's Burning Down the House Talking Heads 80's Bust a Move Young MC 80's Call Me (Extended) Blondie 80's Candy Girl New Edition 80's Cars Gary Numan 80's Com'on Eileen Dexies Midnight Runners 80's Down With The King Run DMC 80's Electric Avenue (Hot Tracks Remix) Eddy Grant 80's Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic The Police 80's Express Yourself Madonna 80's Forever Young Rod Stewart 80's Freakazoids Midnight Star 80's Free Falling Tom Petty 80's Girl You Know it's True (Long) Milli Vanilli 80's Glamorous Life (Club Edit) Sheila E 80's Gloria Laura Branigan 80's Heart of Rock n Roll Huey Lewis 80's I Can't Go For That (No Can Do) Hall & Oates 80's I Go To Work Kool Moe Dee 80's I Know You Got Soul Eric B. & Rakim 80's I Love Rock n Roll Joane Jett 80's It's Like That Run DMC 80's It's Tricky Run DMC 80's Jam-Master Jay Run DMC 80's Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 80's Justify My Love Madonna 80's King Of Rock Run DMC 80's Kiss On My List Hall & Oates 80's Lean On Me Club Nouveau 80's Let It Whip (Ultimix) The Dazz Band 80's Let's Groove Earth Wind and Fire 80's Listen To Your Heart Roxette 80's Madonna - Mega Mix Madonna 80's Maneater Hall & Oates 80's Mary Mary Run DMC 80's Megamixx Herbie Hancock 80's Message Of Love The Pretenders 80's Mickey Toni Basil 80's Mr.