Being Heard Being Heard Being Me Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Musical Play in Three Acts

Library of Congress Meet the Mamma Title Page MEET THE MAMMA By Zora Neale Hurston MEET THE MAMMA A Musical Play in Three Acts. By Zora Neale Hurston TIME: Present. PLACE: New York, U.S.A.; the high seas; Africa. PERSONS: Hotel Proprietor - Peter Thorpe His Wife Carrie Her Mother Edna Frazier His Friend, a lawyer -Bill Brown The Cashier The uncle in Africa Clifford Hunt Meet the Mamma http://www.loc.gov/resource/mhurston.0201 Library of Congress The Princess Waitresses Bell Hops Warriors Guests, etc. Act I, Scene I -2- ACT I. SCENE 1. HOTEL BOOKER WASHINGTON, N. Y. C. SETTING: One-half of stage (left) is dining room, the other is a lobby (right), with desk, elevator, etc. The dining room is set with white cloths, etc. Elevator is upstage exit (center). There is a swinging door exit right and left. ACTION: As the curtain goes up, singing and dancing can be heard, and as it ascends the chorus of waitresses and bellhops are discovered singing and dancing about the lobby and dining room. (7-9 minutes). CASHIER: (looking off stage right) Psst! Here comes the boss! (Everyone scurries to his or her position and pretends to be occupied. Enter boss, right, in evening clothes and cane. Walks wearily through lobby and dining room and back again, speaking to everyone in a hoarse whisper) BOSS: Have you seen my mother-in-law? (Everyone answers "No". Meet the Mamma http://www.loc.gov/resource/mhurston.0201 Library of Congress BOSS: It wont be long now before she comes sniffing and whiffing around. -

Record Collectibles

Unique Record Collectibles 3-9 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in gold vinyl with 7 inch Hound Dog picture sleeve embedded in disc. The idea was Elvis then and now. Records that were 20 years apart molded together. Extremely rare, one of a kind pressing! 4-2, 4-3 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-3 Elvis As Recorded at Madison 3-11 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in black and blue vinyl. Side A has a Square Garden AFL1-4776 Made in blue vinyl with blue or gold labels. picture of Elvis from the Legendary Performer Made in clear vinyl. Side A has a picture Side A and B show various pictures of Elvis Vol. 3 Album. Side B has a picture of Elvis from of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the Aloha playing his guitar. It was nicknamed “Dancing the same album. Extremely limited number from Hawaii album. Side B has a picture Elvis” because Elvis appears to be dancing as of experimental pressings made. of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the same the record is spinning. Very limited number album. Very limited number of experimental of experimental pressings made. Experimental LP's Elvis 4-1 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-8 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 4-10, 4-11 Elvis Today AFL1-1039 Made in blue vinyl. Side A has dancing Elvis Made in gold and clear vinyl. Side A has Made in blue vinyl. Side A has an embedded pictures. Side B has a picture of Elvis. Very a picture of Elvis from the inner sleeve of bonus photo picture of Elvis. -

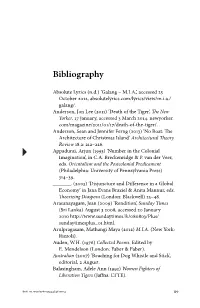

Bibliography

Bibliography Absolute Lyrics (n.d.) ‘Galang – M.I.A.’, accessed 25 October 2012, absolutelyrics.com/lyrics/view/m.i.a./ galang/. Anderson, Jon Lee (2011) ‘Death of the Tiger’, The New Yorker, 17 January, accessed 3 March 2014. newyorker. com/magazine/2011/01/17/death-of-the-tiger/. Anderson, Sean and Jennifer Ferng (2013) ‘No Boat: The Architecture of Christmas Island’ Architectural Theory Review 18.2: 212–226. Appadurai, Arjun (1993) ‘Number in the Colonial Imagination’, in C.A. Breckenridge & P. van der Veer, eds. Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press) 314–39. _______. (2003) ‘Disjuncture and Difference in a Global Economy’ in Jana Evans Braziel & Anita Mannur, eds. Theorizing Diaspora (London: Blackwell) 25–48. Arasanayagam, Jean (2009) ‘Rendition’, Sunday Times (Sri Lanka) August 3 2008, accessed 20 January 2010 http://www.sundaytimes.lk/080803/Plus/ sundaytimesplus_01.html. Arulpragasam, Mathangi Maya (2012) M.I.A. (New York: Rizzoli). Auden, W.H. (1976) Collected Poems. Edited by E. Mendelson (London: Faber & Faber). Australian (2007) ‘Reaching for Dog Whistle and Stick’, editorial, 2 August. Balasingham, Adele Ann (1993) Women Fighters of Liberation Tigers (Jaffna: LTTE). DOI: 10.1057/9781137444646.0014 Bibliography Balint, Ruth (2005) Troubled Waters (Sydney: Allen & Unwin). Bastians, Dharisha (2015) ‘In Gesture to Tamils, Sri Lanka Replaces Provincial Leader’, New York Times, 15 January, http://www. nytimes.com/2015/01/16/world/asia/new-sri-lankan-leader- replaces-governor-of-tamil-stronghold.html?smprod=nytcore- ipad&smid=nytcore-ipad-share&_r=0. Bavinck, Ben (2011) Of Tamils and Tigers: A Journey Through Sri Lanka’s War Years (Colombo: Vijita Yapa and Rajini Thiranagama Memorial Committee). -

Borderlands E-Journal

borderlands e-journal www.borderlands.net.au VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1, 2012 Missing In Action By all media necessary Suvendrini Perera School of Media, Culture & Creative Arts, Curtin University This essay weaves itself around the figure of the hip-hop artist M.I.A. Its driving questions are about the impossible choices and willed identifications of a dirty war and the forms of media, cultural politics and creativity they engender; their inescapable traces and unaccountable hauntings and returns in diasporic lives. In particular, the essay focuses on M.I.A.’s practice of an embodied poetics that expresses the contradictory affective and political investments, shifting positionalities and conflicting solidarities of diaspora lives enmeshed in war. In 2009, as the military war in Sri Lanka was nearing its grim conclusion, with what we now know was the cold-blooded killing of thousands of Tamil civilians inside an official no-fire zone, entrapped between two forms of deadly violence, a report in the New York Times described Mathangi ‘Maya’ Arulpragasam as the ‘most famous member of the Tamil diaspora’ (Mackey 2009). Mathangi Arulpragasam had become familiar to millions across the globe in her persona as the hip-hop performer M.I.A., for Missing in Action. In the last weeks of the war, she made a number of public appeals on behalf of those trapped by the fighting, including a last-minute tweet to Oprah Winfrey to save the Tamils. Her appeal, which went unheeded, was ill- judged and inspired in equal parts. It suggests the uncertain, precarious terrain that M.I.A. -

Professors to Discuss War Issues

NONPROFIT ORGANIZATION WITH NINE QUARTERBACKS, THERE WILL BE A FIGHT TO START PAGE 4 U.S. POSTAGE BATTLE FOR THE BALL: PAID BAYLOR UNIVERSITY ROUNDING UP CAMPUS NEWS SINCE 1900 THE BAYLOR LARIAT FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2008 Professors Keston to discuss Institute war issues unveils An open dialogue led by Baylor religious alum and Dr. Ellis to talk about Christian perspectives abuse By Stephen Jablonski Reporter A collection of When Dr. Marc Ellis, director of the Center communist memorabilia for Jewish Studies and universtiy professor, put on display in mentioned a lack of discussion on the moral dilemma of war in Christianity last semester, Carroll Library the notion rang true with Baylor alumnus Adam Urrutia. This proposal culminated a presentation and discussion of topics relevant By Anita Pere to Christians in a world at war. Staff writer Baylor professors will discuss “Being Chris- tian in a Nation at War … What Are We to Say?” Oppression resonates at 3:30 p.m. Feb. 12 in the Heschel Room of through history as a bruise on the Marrs McLean Science Building. Co-spon- the face of humanity. sored by the Center for Jewish Studies and Many of the world’s citi- the Institute for Faith and Learning, the event zens, grappling with constantly was first conceived by Urrutia, who, Ellis said, changing political regimes and took the initiative to organize the discussion. civil unrest, have never known “This issue is particularly close to what I’m civil liberties. interested in,” Urrutia said. “I’m personally a But one cornerstone of all pacifist and I thought this would be a good societies has survived the test opportunity to discuss this with people.” Associated Press of oppression: religion. -

Sound Matters: Postcolonial Critique for a Viral Age

Philosophische Fakultät Lars Eckstein Sound matters: postcolonial critique for a viral age Suggested citation referring to the original publication: Atlantic studies 13 (2016) 4, pp. 445–456 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2016.1216222 ISSN (online) 1740-4649 ISBN (print) 1478-8810 Postprint archived at the Institutional Repository of the Potsdam University in: Postprints der Universität Potsdam Philosophische Reihe ; 119 ISSN 1866-8380 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-98393 ATLANTIC STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 13, NO. 4, 445–456 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2016.1216222 Sound matters: postcolonial critique for a viral age Lars Eckstein Department of English and American Studies, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This essay proposes a reorientation in postcolonial studies that takes Sound; M.I.A.; Galang; music; account of the transcultural realities of the viral twenty-first century. postcolonial critique; This reorientation entails close attention to actual performances, transculturality; pirate their specific medial embeddedness, and their entanglement in modernity; Great Britain; South Asian diaspora concrete formal or informal material conditions. It suggests that rather than a focus on print and writing favoured by theories in the wake of the linguistic turn, performed lyrics and sounds may be better suited to guide the conceptual work. Accordingly, the essay chooses a classic of early twentieth-century digital music – M.I.A.’s 2003/2005 single “Galang”–as its guiding example. It ultimately leads up to a reflection on what Ravi Sundaram coined as “pirate modernity,” which challenges us to rethink notions of artistic authorship and authority, hegemony and subversion, culture and theory in the postcolonial world of today. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

PRESSEHEFT Kinostart

PRESSEHEFT Kinostart: 22. November 2018 Im Verleih von Rapid Eye Movies INHALT Credits / Filmdaten ....................................................................................................................... 3 Synopsis ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Bio-/Filmografie Regie .................................................................................................................. 4 Über die Produktion und die besondere Beziehung zwischen M.I.A. und Steve Loveridge ........ 5 Über das Team .............................................................................................................................. 9 Songliste des Films ........................................................................................................................ 9 Pressestimmen ........................................................................................................................... 15 Kontakte ..................................................................................................................................... 16 2 MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. Ein Film von Steve Loveridge CREDITS Regie & Produktion: Steve Loveridge Mit: Maya Arulpragasam Kamera: Graham Boonzaaier, Catherine Goldsmith, Matt Wainwright Schnitt: Marina Katz, Gabriel Rhodes Musik: Dhani Harrison, Paul Hicks Music Supervisor: Tracy McKnight Sound Design: Ron Bochar Produzenten: Lori Cheatle, Andrew Goldman, Paul Mezey Ausführende Produzenten: -

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Cabin Chapel Second Edition

Cabin Chapel Second Edition Welcome to Summer! This resource allows you to have family worship while you are away. Cabin Chapel is an easy-to-follow format with a variety of songs, prayers, and scriptures to make your service special to you. There’s even a companion CD, so you can sing along! The Worship Service Opening Prayer (choose one and have someone light a candle as you pray) Creation Prayer O God, giver and sustainer of life. You created the galaxies, all creatures, and my own self. Bless your creation and bless this day that we may serve you and grow to love you every day. Amen. Prayer of Saint Francis of Assisi Lord, make us instruments of your peace. Where there is hatred, let us sow love; Where there is injury, pardon. Where there is discord, union. Where there is doubt, faith. Where there is despair, hope. Where there is darkness, light. Where there is sadness, joy. Grant that we may not so much seek to be consoled as to console, To be understood as to understand, to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; And it is in dying that we are born to eternal life. Amen Morning Prayer of Martin Luther I give you thanks, heavenly Father, through Jesus Christ your dear Son, that you have protect- ed me through the night from all harm and danger. I ask that you would also protect me today from sin and all evil, so that my life and actions may please you. -

Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG

Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Adam & Evil After Loving You Ain't That Lovin' You Baby All I Needed Was Rain All Shook Up All Shook Up (Live) All That I Am Almost Almost Always True Almost In Love Always On My Mind Am I Ready Amazing Grace America The Beautiful American Trilogy And I Love You So And The Grass Won't Pay No Mind Angel Any Day Now Any Place In Paradise Any Way You Want Me Anyone Could Fall In Love With You Anything That's Part Of You Are You Lonesome Tonight Are You Lonesome Tonight Are You Sincere As Long As I Have You Ask Me Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Baby I Don't Care Baby Let's Play House Beach Boy Blues Beyond The Bend Big Boots Big Boss Man Big Hunk O' Love, A (Live) Aloha Concert Big Love, Big Heartache Bitter They Are, Harder They Fall Blue Christmas Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain Blue Hawaii Blue Moon Blue Suede Shoes Blue Suede Shoes Blueberry Hill Blueberry Hill/I Can't Stop Loving (Medley) Bosom Of Abraham Bossa Nova Baby Boy Like Me, A Girl Like You, A Bridge Over Troubled Water (Live) Bringin' It Back Burning Love (Live) Aloha Concert By & By Can't Help Falling In Love Change Of Habit Charro Cindy, Cindy Clean Up Your Own Back Yard C'mon Everybody Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Crawfish Cross My Heart, Hope To Die Crying In The Chapel Danny Boy Devil In Disguise Didja Ever Dirty Dirty Feeling Dixieland Rock Do Not Disturb Do You Know Who I Am Doin' The Best I Can Don't Don't Ask Me Why Don't Be Cruel Don't Cry Daddy Don't Leave Me Now Don't Think Twice Don'tcha Think It's Time Down By The Riverside/When The Saints