13895 Wagner News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

July 8-18, 2021

July 8-18, 2021 Val Underwood Artistic Director ExecutiveFrom Directorthe Dear Friends: to offer a world-class training and performance program, to improve Throughout education, and to elevate the spirit of history, global all who participate. pandemics have shaped society, We are delighted to begin our season culture, and with Stars of Tomorrow, featuring institutions. As many successful young alumni of our we find ourselves Young Singer Program—including exiting the Becca Barrett, Stacee Firestone, and COVID-19 crisis, one pandemic and many others. Under the direction subsequent recovery that comes to of both Beth Dunnington and Val mind is the bubonic plague—or Black Underwood, this performance will Death—which devastated Europe and celebrate the art of storytelling in its Asia in the 14th century. There was a most simple and elegant state. The silver lining, however, as it’s believed season also includes performances that the socio-economic impacts of by many of our very own, long- the Plague on European society— time Festival favorites, and two of particularly in Italy—helped create Broadway’s finest, including HPAF the conditions necessary for what is Alumna and 1st Place Winner of arguably the greatest post-pandemic the 2020 HPAF Musical Theatre recovery of all time—the Renaissance. Competition, Nyla Watson (Wicked, The Color Purple). Though our 2021 Summer Festival is not what was initially envisioned, As we enter the recovery phase and we are thrilled to return to in-person many of us eagerly await a return to programming for the first time in 24 “normal,” let’s remember one thing: we months. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

The Exhibition FEBRUARY 2015 Der Meister Tön' Und Weisen... Heinz Zednik – 50 Jahre Staatsoper

Der Meister Tön’ und Weisen... Heinz Zednik – 50 Jahre Staatsoper 12.2.–21.9.2015 Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien [email protected] T +43 1 525 24 5315 FEBRUARY 2015 The Exhibition In 2015 the music world honours the occasion of two anniversaries of the well-known and popular Austrian tenor Heinz Zednik: he celebrates both his seventy-fifth birthday and five decades as member of the ensemble of the “Haus am Ring”, the Vienna State Opera. On November 5, 1964 the young singer from the Graz Opera gave his first guest performance in Vienna, singing the role of Augustin Moser in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg; on September 3, 1965 he appeared for the first time as a full member of the ensemble at the Vienna State Opera – as Count Lerma in Verdi’s Don Carlo. In order to showcase Zednik’s impressive repertory the exhibition focuses both on Zednik’s opera performances in Vienna and beyond – in Milan, Bayreuth and New York – and his work outside the field of opera, which comprises operetta, oratories, lieder and Viennese songs. Markus Vorzellner curated the exhibition; Elisabeth Truxa designed the layout. Der Meister Tön’ und Weisen... Heinz Zednik – 50 Jahre Staatsoper 12.2.–21.9.2015 Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien [email protected] T +43 1 525 24 5315 Events RECITAL HEINZ ZEDNIK Piano: Konrad Leitner Wednesday, April 22, 7.30 p.m. Tickets € 22, Verein Freunde der Wiener Staatsoper and Ö1 Club € 19, students € 12 Reservations T +43 1 525 24 3460 „A MUSI, A MUSI“ A viennese evening with Heinz Zednik, Peter Hawlicek (contra guitar) und Roland Sulzer (accordeon) Moderation: Markus Vorzellner Wednesday, September 9, 7.30 p.m Tickets € 22, Verein Freunde der Wiener Staatsoper and Ö1 Club € 19, students € 12 Reservations T +43 1 525 24 3460 „…DASS SICH DIE WELT IN EINEM TAG HERUMDREHT“ After a guided tour through the exhibition by curator Markus Vorzellner you are invited to enjoy his anecdotes of personal encounters with Heinz Zednik, complemented by selected audio-clips. -

Wagner Sept 2012.Indd

Wagner Society in NSW Inc. Maximise your enjoyment and understanding of Wagner’s music Newsletter No. 126, September 2012 In Memoriam DENIS CONDON Piano Historian & Collector Dies - Article Below President’s Report Welcome to the third newsletter for 2012. STOP PRESS 1: It has been an exciting time for us Wagner lovers. First, our patron, Simone Young somehow managed to fi t us On 12 August a capacity audience of Members into an incredibly busy schedule, and was the star of our and guests met our Patron, Simone Young AO. last function, on 12 August. An unprecedented number A large group went north to hear the Hamburg attended the event – 160 in all - including a quite a few Opera Orchestra and cast of Das Rheingold in two non-members, some of whom joined the Society on the sensational performances. spot. The fi rst part of the meeting consisted of an interview between Francis Merson and Maestra Young (I refuse to call her “Maestro,” so henceforth she will be “Simone”). Francis is the editor of Limelight Magazine, and he asked a number of interesting questions about Simone’s background and her future plans. Simone, who was amazingly relaxed, given her other commitments, gave very full responses about her musical experiences, and spoke in an extremely frank and sometimes self-deprecating manner. We were treated to a number of anecdotes from her life, delivered with great humour. Some of them are described in detail later in this newsletter. As to her future plans, she is committed to remain in Hamburg until the end of the 2015 season, at which time she proposes to do freelance work. -

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV With onstage guests directors Brian Large and Jonathan Miller & former BBC Head of Music & Arts Humphrey Burton on Wednesday 30 April BFI Southbank’s annual Broadcasting the Arts strand will this year examine Opera on TV; featuring the talents of Maria Callas and Lesley Garrett, and titles such as Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) and The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), this season will show how television helped to democratise this art form, bringing Opera into homes across the UK and in the process increasing the public’s understanding and appreciation. In the past, television has covered opera in essentially four ways: the live and recorded outside broadcast of a pre-existing operatic production; the adaptation of well-known classical opera for remounting in the TV studio or on location; the very rare commission of operas specifically for television; and the immense contribution from a host of arts documentaries about the world of opera production and the operatic stars that are the motor of the industry. Examples of these different approaches which will be screened in the season range from the David Hockney-designed The Magic Flute (Southern TV/Glyndebourne, 1978) and Luchino Visconti’s stage direction of Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) to Peter Brook’s critically acclaimed filmed version of The Tragedy of Carmen (Alby Films/CH4, 1983), Jonathan Miller’s The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), starring Lesley Garret and Eric Idle, and ENO’s TV studio remounting of Handel’s Julius Caesar with Dame Janet Baker. Documentaries will round out the experience with a focus on the legendary Maria Callas, featuring rare archive material, and an episode of Monitor with John Schlesinger’s look at an Italian Opera Company (BBC, 1958). -

About the Exhibition Tenorissimo! Plácido Domingo in Vienna

Tenorissimo! Plácido Domingo in Vienna May 17th, 2017 - January 8th, 2018 Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien [email protected] T +43 1 525 24 5315 About the exhibition An unmistakable dark timbre, highly dramatic expressiveness, an impressive, vast repertoire – all this enraptures the fans of the Spanish crowd-pleaser with waves of enthusiasm. The Theatermuseum celebrates Plácido Domingo on the anniversary of his stage debut: He has been singing at the Vienna State Opera for 50 years. When the Tenor, then still considered as insider tip, made his debut at the State Opera in the title role of Verdi‘s Don Carlo, not only he took stage and cast in storm, but also the hearts of the Viennese audience – a true love relationship, unbroken till today. This performance contributed to an unparalleled career, taking him to the world‘s leading opera houses. Vienna has always been a very special “home port“ for the opera star. Here he performed 30 different roles in 300 shows and was awarded the title Austrian Kammersänger. The exhibition at the Theatermuseum documents the most important appearances of the “Tenorissimo“ in Vienna with original costumes and props, photographs and memorabilia, video and audio samples. The presentation portrays him also as baritone, the role fach on which he concentrated almost exclusively in the past 10 years, and refers to his activities as conductor, taking him regularly to the orchestra pit of the Vienna State Opera since the end of the 1970s. Without hesitation Plácido Domingo can be described as one of the most versatile, curious and longest serving representative of his musical genre. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

The Wagner Society Members Who Were Lucky Enough to Get Tickets Was a Group I Met Who Had Come from Yorkshire

HARMONY No 264 Spring 2019 HARMONY 264: March 2019 CONTENTS 3 From the Chairman Michael Bousfield 4 AGM and “No Wedding for Franz Liszt” Robert Mansell 5 Cover Story: Project Salome Rachel Nicholls 9 Music Club of London Programme: Spring / Summer 2019 Marjorie Wilkins Ann Archbold 18 Music Club of London Christmas Dinner 2018 Katie Barnes 23 Visit to Merchant Taylors’ Hall Sally Ramshaw 25 Dame Gwyneth Jones’ Masterclasses at Villa Wahnfried Roger Lee 28 Sir John Tomlinson’s masterclasses with Opera Prelude Katie Barnes 30 Verdi in London: Midsummer Opera and Fulham Opera Katie Barnes 33 Mastersingers: The Road to Valhalla (1) with Sir John Tomlinson Katie Barnes 37 Mastersingers: The Road to Valhalla (2) with Dame Felicity Palmer 38 Music Club of London Contacts Cover picture: Mastersingers alumna Rachel Nicholls by David Shoukry 2 FROM THE CHAIRMAN We are delighted to present the second issue of our “online” Harmony magazine and I would like to extend a very big thank you to Roger Lee who has produced it, as well as to Ann Archbold who will be editing our Newsletter which is more specifically aimed at members who do not have a computer. The Newsletter package will include the booking forms for the concerts and visits whose details appear on pages 9 to 17. Overseas Tours These have provided a major benefit to many of our members for as long as any us can recall – and it was a source of great disappointment when we had to suspend these. Your committee have been exploring every possible option to offer an alternative and our Club Secretary, Ian Slater, has done a great deal of work in this regard. -

Wagner Intoxication

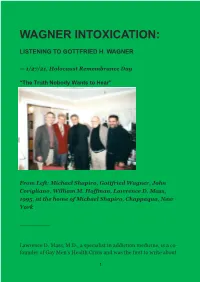

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

A MOZART GALA from Salzburg

UNITEL and CLASSICA present A MOZART GALA from Salzburg PATRICIA PETIBON MAGDALENA KOŽENÁ EKATERINA SIURINA MICHAEL SCHADE THOMAS HAMPSON ANNA NETREBKO RENÉ PAPE DANIEL HARDING A MOZART GALA from Salzburg Patricia Petibon René Pape Daniel Harding Magdalena Kožená Thomas Hampson Ekaterina Siurina Anna Netrebko Michael Schade Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart he most spectacular homage to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on his 250th birthday in 2006 was incontestably Conductor Daniel Harding the presentation of all of his operas and operatic Orchestra Wiener Philharmoniker T fragments at the Salzburg Festival, “Mozart22”. Recorded on Soloists Anna Netrebko film (available from Unitel Classica), this monumental project Magdalena Kožená has been preserved for posterity as a benchmark of Mozart Ekaterina Siurina interpretation in the early 21st century. Patricia Petibon Thomas Hampson The “Mozart Gala“ held at the Felsenreitschule on 30 René Pape July 2006, in the first days of the 2006 Salzburg Festival, Michael Schade presents a kind of microcosm of the Mozart festivities, with Directed by Brian Large a selection of arias and orchestral music performed by the Vienna Philharmonic under Daniel Harding and featuring Don Giovanni Overture some of the top vocalists of the 2006 Salzburg Festival. A “Madamina, il catalogo è questo“ (René Pape) sampling of exquisite hors d‘œuvres prepared by the most “Dalla sua pace“ (Michael Schade) outstanding musical chefs! Mitridate, Re di Ponto Internationally celebrated soprano Anna Netrebko lives “Nel grave tormento“ (Patricia Petibon) up to her reputation as a fiery, dramatic diva in her passionate La clemenza di Tito rendition of Elettra‘s aria “D‘Oreste, d‘Aiace” from Idomeneo.