Eyes on Their Fingertips?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Design for Component A

Consultancy Services for Implementation of Component-A of Last Mile Connectivity of NCRMP TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT Version: 2.0 Credit # 4772-IN Submitted by: Telecommunications Consultants India Limited TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash Part – I New Delhi- 110 048, India. TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT TCIL Document Details Project Title Consultancy Services for Implementation of Component-A of Last Mile Connectivity of National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project (NCRMP) Report Title Technical Design Report Report Version Version 2.0 Client State Project Implementation Unit (SPIU) National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project - Kerala (NCRMP- Kerala) Department of Disaster Management Government of Kerala Report Prepared by Project Team Date of Submission 19.12.2018 TCIL’s Point of Contact Mr. A. Sampath Kumar Team Leader Telecommunications Consultants India Limited TCIL Bhawan, Greater Kailash-I New Delhi-110048 [email protected] Private & Confidential Page 2 TECHNICAL DESIGN REPORT TCIL Contents List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 9 2. EARLY WARNING DISSEMINATION SYSTEM .......................................................................................... 9 3. Objective of the Project ..................................................................................................................... -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

Annual Report 2013 - 2014

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 2014 KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD KSBB ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 2014 Published by: Dr. K. P. Laladhas Member Secretary KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD L-14, Jai Nagar, Medical College P.O., Thiruvananthapuram Ph: 0471-2554740, Telefax: 0471-2448234 Email: [email protected] Website: www.keralabiodiversity.org Design and layout www.communiquetvm.tumblr.com Cover Photo Gokul R. Purple Moorhen Photo: Riyas Arun T. KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD 53 KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 1 3 - 2 0 1 4 L14, Jainagar, Medical College.P.O Thiruvananthapuram - 695 011 KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD 1 2 KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD C O N T E N T S 7 DOCUMENTATION OF BIODIVERSITY THROUGH PEOPLE’S BIODIVERSITY REGISTER (PBR) 9 MARINE BIODIVERSITY REGISTER (MBR) 10 STRENGTHENING BMC 12 CONSERVATION PROGRAMMES 21 BIODIVERSITY RESEARCH CENTRE 22 REGULATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS 23 POLICY ISSUES AND ADVICE TO GOVERNMENT 26 NATURE EDUCATION 29 BIODIVERSITY AWARENESS PROGRAMMES 31 WORKSHOP/ SEMINARS 34 AWARDS/ RECOGNITIONS 37 PUBLICATIONS 40 REPRESENTATION IN EXPERT COMMITTEES AND OUTREACH PROGRAMMES 43 FUTURE PLANS 45 AUDITED STATEMENTS OF ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR 2013-14 KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD 3 Dr.Oommen.V.Oommen Chairman Prelude In October 2010 in Nagoya, Japan, over 190 countries around the world reached a historic global agreement to take urgent action to halt the loss of biodiversity. The international community is eagerly looking out for the 12th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity with focus on sustainable development from 6 - 17 October 2014 at Pyeongchang, South Korea. This is the time for reckoning by all committed to safeguarding the variety of life on Earth. -

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

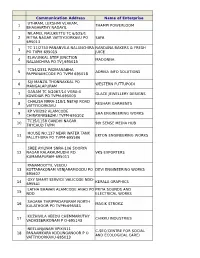

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

Highland Oaks Activity Calendar July 2020

went on a successful tour in Europe and returned November 1983 designating the third Monday of to the U.S. to perform, co-write songs, play on January an annual legal public holiday observing other musicians’ songs, and produce albums. He the birth of King. It was first celebrated in January also continued to release hit after hit. His next 1986.) Wonder continues his songwriting, successful album was a double one called Songs recording, performing, and advocacy. His legacy in the Key of Life, and it was released in includes having more than 30 top 10 hits both on September 1976. In 1980, Wonder released the the pop and rhythm and blues charts in the U.S., very successful album, Hotter Than July. One of winning 25 Grammys® , one Academy Award® for the singles from that album was Happy Birthday. Best Original Song (in 1985 for I Just Called to Say This song was used in his campaign to make Dr. I Love You), and receiving numerous awards in the Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birth anniversary a U.S. and other countries. Highland Oaks national holiday in the U.S. (Legislation passed in At Water Run July 2020 become a hit was Fingertips. In 1963, it became Music Notes: the No. 1 song on Billboard’s pop charts. His next A Biography of Stevie Wonder hit was Uptight (Everything’s Alright) that was released in 1965. It reached No.1 on the rhythm “Music, at its essence, is what gives us memories. and blues chart and No. 3 on the pop chart. -

Celebran a Stevie Wonder

EL DIARIO DE SONORA JUEVES 12 de Febrero del 2015 Premier 21 ESPECIAL Melissa Celebran Rivers rinde tributo a su a Stevie madre LOS ÁNGELES.- La hija de la falle- cida Joan Rivers, Melissa, rinde ho- menaje a su madre en un libro ti- Wonder tulado ‘The Book of Joan: Tales of Mirth, Mischief, and Manipulation’ LOS ÁNGELES Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours”; y la (El Libro de Joan: Cuentos de Risas, ›› La fiesta post hija de Wonder, Aisha, interpretó Travesuras y Manipulación), un tri- la canción compuesta para ella — buto con el que comparte momen- Grammy oficial fue un “Isn’t She Lovely” — con Ne-Yo. tos divertidos, “observaciones irre- concierto en homenaje “Te amo papi”, dijo Aisha, de verentes” y anécdotas vividas junto pie junto a su padre quien estuvo a la humorista. al ícono del piano, en primera fila. La noticia de la publicación de Beyonce abrió el show El resto de la noche se desarro- esta obra, que llevará a cabo la edi- lló como una carta de amor para torial Crown Archetype, llega tres La fiesta post Grammy oficial fue Wonder. días después de que Melissa acep- un concierto en homenaje a Stevie Gaga dijo que el primer CD que tara en nombre de su madre el Wonder. tocó era uno de Wonder. Grammy póstumo a Mejor Álbum Beyonce, Lady Gaga, Pharrell y “De verdad eres la razón por Stevie Wonder cerró el show con un popurrí de sus canciones. Hablado por ‘Diary of a Mad Di- Annie Lennox reconocieron al íco- la que estoy aquí hoy, gracias”, di- va’ (Diario de una Diva Loca), un no del piano con un concierto en jo Gaga, de 28 años, quien recibió con una versión magistral de “My Songs in the Key of Life — An All- audio grabado el mismo año de su Los Angeles, a pocos días de la ce- una ovación por su versión de “I Cherie Amour”. -

Stevie Wonder

lifestyle THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2015 My ideal make up brushes kit very girl struggles with finding the right make up brushes kit to use. Many The brushes are things vary from one girl to the next, the way you hold the brush, the hand E05 - Eye Liner: Creates smooth and even lines. You can use it with gel or liquid liners. Eyou’re comfortable using while applying make-up and also how you feel E30 - Pencil: Softens and smokes out lines. Softens pencil liners along the top and bot- about using it. Many people prefer different brands. Personally, I love brushes tom lash lines, or use to highlight the inner corner of your eyes. that have multiple purposes. I tend to use an eye shadow brush to define my E40 - Tapered Blending: For a softy blended crease. Using just the tips to apply color, contour on my cheeks sometimes, a powder brush to highlight, and even lip sweep back and forth through the crease for a diffused and blended finish. brushes to define the eye shadow on my lower lashes. It’s all about what is E55 - Eye Shading: Even application of color. Place the color across the whole lid for an more comfortable to use, and with thousands of options to choose from, it even and strong application of the product. can get a bit confusing. E60 - Large Shader: Uniformly covers the whole lid with the product. Apply a cream A few things you should consider before purchasing your shadow base or cream shadows for a quick and even coverage. -

Imagine Waking up Each Morning and Wondering Who Will Have Changed. Illustrated by Richard Wagner

GLASS EYES IN PORCELAIN FACES JACK WESTLAKE IMAGINE WAKING UP EACH MORNING AND WONDERING WHO WILL HAVE CHANGED. ILLUSTRATED BY RICHARD WAGNER IMAGINE THAT BEING THE FIRST THING YOU THINK OF AS YOU WAKE 40 Imagine that being the first thing you think of as you wake. As you get out of bed. As you shower, dress, eat breakfast. As you walk out the door and head to work. Imagine what it’s like to get on the tube, scan- ning the packed carriage for a too-perfect face, for a pair of eyes more vacant than all the others. Imagine seeing such a face on the head of someone whose name you don’t know, but who you recognise from your commute at the start of each day. Someone you always nod to, and who always nods back as you both sway and jolt with the move- ment of the carriage, acknowledgment that never develops into con- versation. Imagine seeing them one morning – this morning – like usual. Now imagine that their face has changed, apparently overnight. It’s a doll’s face. Near-white porcelain, with wide blue eyes made of glass. Imagine how it feels, knowing that only you can see this. Imag- ine they look at you. Imagine how it feels when, despite the change, despite them not being them anymore, they nod at you like usual. This is what my life has become. At the office building I do my best to avoid the concierge, but it’s no good – you have to pass the main reception desk to get to the lifts. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City District from 14.02.2021To20.02.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City district from 14.02.2021to20.02.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 292/2021/465, TC 35//145(1), Near 48/Mal 20-02- 468, 471, 34 Selvius Raj. SI 1 Nizamudeen Azeez 16th Kal Mandapam, , EAST FORT FORT JFMC II, TVPM e 2021/19:37 IPC & 14(b) of of Police Vallakkadavu Foreigner Act TC 43/1200, 292/2021/465, Puthuvalputhen 41/Mal 20-02- 468, 471, 34 Selvius Raj. SI 2 Anand Rajappan, Veedu, Near Manacaud FORT JFMC II, TVPM e 2021/19:37 IPC & 14(b) of of Police Vaduvathu Temple, Foreigner Act Kamaleswaram Kunjukonathu Puthen Pratheesh 31/Mal Veedu, Kozhikode, 18-02- 178/2021/279, 3 Baiju J John Karamana KARAMANA Kumar.SI of STATION BAIL e Anavoor P.O, 2021/15:00 337 IPC Police Perunkadavila village 261/2021/4(2) (d) r/w 5 of THOTTAM VARAVILA Kerala V GANGA 38/Mal VEEDU,NEAR KOVALAM 19-02- 4 SHAJI PODIYAN Epidemic KOVALAM PRASAD. SI of STATION BAIL e MILMA,AMBALATHAR JUNCTION 2021/17:30 Diseases Police A Ordinance 2020 260/2021/4(2) (d) r/w 5 of CHANDRAVILASAM Kerala KRISHNANKUT 52/Mal UPASANA 19-02- SHAJI TC. SI of 5 GOPAKUMAR VEEDU,PANANGODE, Epidemic KOVALAM STATION BAIL TY NAIR e JUNCTION 2021/16:25 Police VENGANOOR Diseases Ordinance 2020 259/2021/. -

Weibull and Gamma Distributions for Wave Parameter Predictions

J. Ind. Geophys. Union ( January 2005 ) Vol.9, No.1, pp.55-64 Weibull and Gamma distributions for Wave Parameter Predictions S.P.Satheesh, V.K.Praveen, V.Jagadish Kumar, G.Muraleedharan1 and P.G.Kurup2 Department of Physical Oceanography, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin-682016 1Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, IIT Delhi, New Delhi-110016 2Amrita Institutions, Ashram Lane, Azad Road, Cochin-682017 e-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT Distribution of maximum wave height follows the model derived on the concept that the individual zero up-crossing wave heights follow the Weibull law. Better results are obtained when a depth factor included to accommodate shallow water attenuation effects. Certain wave height parameters such as mean maximum wave height, most frequent maximum wave height, extreme wave height, return period of an extreme wave and probability of realising an extreme wave in a time less than the designated return period are estimated and compared with computed values giving reliable results. Predicted significant wave heights are comparable with the computed value with maximum deviation of 0.21m. Theoretical and empirical supremacy of Weibull is re-established. A 100.0% empirical support is obtained in the simulation of zero up-crossing wave periods by Gamma at 0.05 level of significance. A Weibull-Gamma (with non-zero correlation) joint distribution simulates more effectively the real 3D plot. INTRODUCTION was offered in terms of the intensity function (Muraleedharan, Unnikrishnan Nair & Kurup 1993). Unlike in deep water, the wave climate in shallow A modified Weibull distribution which includes water exhibits spatial variations owing to complex the depth factor to accommodate the shallow water transformation processes. -

Kjøreplan, Stevie Wonder Bærum Kulturhus 290111 1. Innslipp Vakter

Kjøreplan, Stevie Wonder Bærum kulturhus 290111 Utgave pr 15.11.2013 Nr Hva Hvem Utstyr/Lyd/Lys Stil/tpo Bilder 1. Innslipp vakter Projektor – hele forestillingen Bilde1 2. Fingertips teknikker mp3 Bilde 2 3. Stevie -bilder i loop Anders Oftedal projektor Bilde 3 4. Medley (Part time lover/Ebony and…/Isn`t she…/ Sir Duke/I wish) Korps Fullt band/solo i bandet/sologitar 5 varierte låter bilde 4-8-et for hver låt 5. Kor -intro – kommer gående, syngende inn Kor/band Fullt band 30 kormikker Bilde 9 - korbilde 6. Velkommen til konsert - til kor – over korintro Torkel Snakkemikk venstre Bilde 9 ligger 7. You are the sunshine Kor / piano Piano +30 kormikker Bilde 10 8. You are the sunshine Korps/Eckhard + Bengt Fullt Band – solistmikker i front Bilde 11, Sinatra 9. Velkommen til Odd Renè + takk til Bengt solist fra korpset Øyvind Snakkemikk Høyre Bilde 12, Odd Renè 10. Master Blaster (Jammin) Korps/Kor/Odd Renè Fullt band,30 kormikker,sangsolo Bilde 13 11. Velkommen til Ragnhild Fangel Jamtveit – noen få ord.. Odd Renè Egen mikk Bilde 14, Ragnhild… 12. Living for the city (duet) Storband/Ragnhild/Odd Renè Storband + to sangmikker Bilde 15 13. Superstition Storband/ Odd Renè Stordband + en sanger Bilde 16 14. Litt om forholdet til SW og hans musikk Odd Renè Egen mikk Bilde 16 ligger 15. Overjoyed Piano/ Odd Renè Piano/solist + Vask på horisont Rolig ballade Mute projektor 16. Presentasjon av band og Eckhard + annonsere pause Torkel snakkemikk V+ Vask på horisont Mute projektor 17. Signed, Sealed, Delivered Band/Kor/ Odd Renè + korsolist Band/3 blåsere (1solo)/2 sangere Bilde 17 18. -

U2 All Along the Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 D

U/z U2 All Along The Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel Of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 Discotheque U2 Electrical Storm U2 Elevation U2 Even Better Than The Real Thing U2 Fly U2 Ground Beneath Her Feet U2 Hands That Built America U2 Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 Helter Skelter U2 Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me U2 I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 I Will Follow U2 In A Little While U2 In Gods Country U2 Last Night On Earth U2 Lemon U2 Mothers Of The Disappeared U2 Mysterious Ways U2 New Year's Day U2 One U2 Please U2 Pride U2 Pride In The Name Of Love U2 Sometimes You Can't Make it on Your Own U2 Staring At The Sun U2 Stay U2 Stay Forever Close U2 Stuck In A Moment U2 Sunday Bloody Sunday U2 Sweetest Thing U2 Unforgettable Fire U2 Vertigo U2 Walk On U2 When Love Comes To Town U2 Where The Streets Have No Name U2 Who's Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses U2 Wild Honey U2 With Or Without You UB40 Breakfast In Bed UB40 Can't Help Falling In Love UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Come Back Darling UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Earth Dies Screaming UB40 Food For Thought UB40 Here I Am (Come And Take Me) UB40 Higher Ground UB40 Homely Girl UB40 I Got You Babe UB40 If It Happens Again UB40 I'll Be Yours Tonight UB40 King UB40 Kingston Town UB40 Light My Fire UB40 Many Rivers To Cross UB40 One In Ten UB40 Rat In Mi Kitchen UB40 Red Red Wine UB40 Sing Our Own Song UB40 Swing Low Sweet Chariot UB40 Tell Me Is It True UB40 Train Is Coming UB40 Until