East Texas in World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Texas § City of Brownsville § County of Cameron §

THE STATE OF TEXAS § CITY OF BROWNSVILLE § COUNTY OF CAMERON § Derek Benavides, Secretary Abraham Galonsky, Commissioner Troy Whittemore, Commissioner Aaron Rendon, Commissioner Ruben O’Bell, Commissioner Vanessa Castillo, Commissioner Ronald Mills, Chairman NOTICE OF A PUBLIC MEETING OF THE PLANNING AND ZONING COMMISSION OF THE CITY OF BROWNSVILLE TELECONFERENCE OPEN MEETING Pursuant to Chapter 551, Title 5 of the Texas Government Code, the Texas Open Meetings Act, notice is hereby given that the Planning and Zoning Commission of the City of Brownsville, Texas, has scheduled a Regular Meeting on Thursday, April 1, 2021 at 5:30 P.M. via Zoom Teleconference Meeting by logging on at: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81044265311?pwd=YXZJcWhpdWNvbXNxYjZ5NzZEWUgrZz09 Meeting ID: 810 4426 5311 Passcode: 659924 This Notice and Meeting Agenda, are posted online at: http://www.cob.us/AgendaCenter The members of the public wishing to participate in the meeting hosted through WebEx Teleconference can join at the following numbers: One tap mobile: +13462487799,,81044265311#,,,,*659924# US (Houston) +16699006833,,81044265311#,,,,*659924# US (San Jose) Or Telephone: Dial by your location: +1 346 248 7799 US (Houston) +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) +1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma) +1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago) +1 929 205 6099 US (New York) +1 301 715 8592 US (Washington DC) Meeting ID: 810 4426 5311 Passcode: 659924 Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kbgc6tOoRF Members of the public who submitted a “Public Comment Form” will be permitted to offer public comments as provided by the agenda and as permitted by the presiding officer during the meeting. -

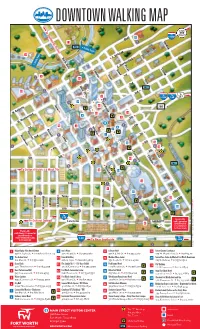

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

Growing up Black in East Texas: Some Twentieth-Century Experiences

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 32 Issue 1 Article 8 3-1994 Growing up Black in East Texas: Some Twentieth-Century Experiences William H. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Wilson, William H. (1994) "Growing up Black in East Texas: Some Twentieth-Century Experiences," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 32 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol32/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATIO:'J 49 GROWING UP BLACK IN EAST TEXAS: SOME TWENTIETH-CENTURY EXPERIENCES f by William H. Wilson The experiences of growing up black in East Texas could be as varied as those of Charles E. Smith and Cleophus Gee. Smith's family moved from Waskom, Harrison County, to Dallas when he was a small child to escape possible violence at the hands of whites who had beaten his grandfather. Gee r matured in comfortable circumstances on the S.H. Bradley place near Tyler. ~ a large farm owned by prosperous relatives. Yet the two men lived the larg er experience of blacks in the second or third generation removed from slav ery, those born, mostly. in the 1920s or early 1930s. Gee, too, left his rural setting for Dallas, although his migration occurred later and was voluntary. -

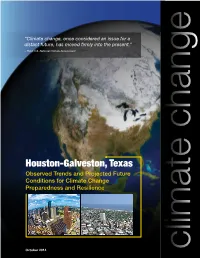

Houston-Galveston Exercise Division

About the National Exercise Program Climate About the National Exercise Program Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional The Third U.S. National Climate Assessment, Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional The Third U.S. National Climate Assessment, Workshops released in May 2014, assesses the science of climate Workshops released in May 2014, assesses the science of climate change and its impacts across the United States, now change and its impacts across the United States, now The Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional Workshops are an element of the the settingThe Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional Workshops are an element of the the setting and throughout this century. It integrates findings of and throughout this century. It integrates findings of overarching Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Exercise Series sponsored by the White overarching Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Exercise Series sponsored by the White the U.S. Global Change Research Program with the the U.S. Global Change Research Program with the House National Security Council Staff, Council on Environmental Quality, and Office of Science House National Security Council Staff, Council on Environmental Quality, and Office of Science results of research and observations from across the results of research and observations from across the and Technology Policy, in collaboration with the National Exercise Division. The workshops and Technology Policy, in collaboration with the NationalThe Houston-Galveston Exercise -

Tyler-Longview: at the Heart of Texas: Cities' Industry Clusters Drive Growth

Amarillo Plano Population Irving Lubbock Dallas (2017): 445,208 (metros combined) Fort Worth El Paso Longview Population growth Midland Arlington Tyler (2010–17): 4.7 percent (Texas: 12.1 percent) Round Rock Odessa The Woodlands New Braunfels Beaumont Median household Port Arthur income (2017): Tyler, $54,339; Longview, $48,259 Austin (Texas: $59,206) Houston San Antonio National MSA rank (2017): Tyler, No. 199*; Longview, No. 204* Sugar Land Edinburg Mission McAllen At a Glance • The discovery of oil in East Texas helped move the region from a reliance on agriculture to a manufacturing hub with an energy underpinning. Tyler • Health care leads the list of largest employers in Tyler and Longview, the county seats of adjacent Gilmer Smith and Gregg counties. Canton Marshall • Proximity to Interstate 20 has supported logistics and retailing in the area. Brookshire Grocery Co. Athens is based in Tyler, which is also home to a Target Longview distribution center. Dollar General is building a regional distribution facility in Longview. Henderson Rusk Nacogdoches *The Tyler and Longview metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) encompass Smith, Gregg, Rusk and Upshur counties. Tyler–Longview: Health Care Growth Builds on Manufacturing, Energy Legacy HISTORY: East Texas Oilfield Changes and by the mid-1960s, Tyler’s 125 manufacturing plants Agricultural Economies employed 8,000 workers. Th e East Texas communities of Tyler and Longview, Longview, a cotton and timber town before the though 40 miles apart, are viewed as sharing an economic oil boom, attracted newcomers from throughout the base and history. Tyler’s early economy relied on agricul- South for its industrial plants. -

Total Population

HOW WE COMPARE Diversity . Education . Employment . Housing . Income . Transportation ____________________________________________ Houston’s Comparison with Major U.S. Cities April 2009 CITY OF HOUSTON Planning and Development Department Public Policy Division CITY OF HOUSTON Planning and Development Dept. Public Policy Division April 2009 HOW WE COMPARE Diversity . Education . Employment . Housing . Income . Transportation ____________________________________________ Table of Contents • Population o Figure 1: Total Population o Figure 2: Population Change o Figure 3: Male and Female Population o Figure 4: Population by Race\Ethnicity o Figure 5: Age 18 Years and Over o Figure 6: Age 65 Years and Over o Figure 7: Native and Foreign born • Households o Figure 8: Total Households o Figure 9: Family and Non-Family Households o Figure 10: Married Couple Family o Figure 11: Female Householder – No husband Present o Figure 12: Average Household Size o Figure 13: Marital Status • Education o Figure 14: Educational Attainment o Figure 15: High School Graduates o Figure 16: Graduate and Professional • Income & Poverty o Figure 17: Median Household Income o Figure 18: Individuals Below Poverty Level o Figure 19: Families Below Poverty Level • Employment o Figure 20: Not in Labor Force o Figure 21: Employment in Educational, Health & Services o Figure 22: Unemployment Rate for Cities o Figure 23: Unemployment Rate for Metro Areas o Figure 24: Class of Workers CITY OF HOUSTON Planning and Development Dept. Public Policy Division April 2009 HOW WE -

District 16 District 142 Brandon Creighton Harold Dutton Room EXT E1.412 Room CAP 3N.5 P.O

Elected Officials in District E Texas House District 16 District 142 Brandon Creighton Harold Dutton Room EXT E1.412 Room CAP 3N.5 P.O. Box 2910 P.O. Box 2910 Austin, TX 78768 Austin, TX 78768 (512) 463-0726 (512) 463-0510 (512) 463-8428 Fax (512) 463-8333 Fax 326 ½ N. Main St. 8799 N. Loop East Suite 110 Suite 305 Conroe, TX 77301 Houston, TX 77029 (936) 539-0028 (713) 692-9192 (936) 539-0068 Fax (713) 692-6791 Fax District 127 District 143 Joe Crab Ana Hernandez Room 1W.5, Capitol Building Room E1.220, Capitol Extension Austin, TX 78701 Austin, TX 78701 (512) 463-0520 (512) 463-0614 (512) 463-5896 Fax 1233 Mercury Drive 1110 Kingwood Drive, #200 Houston, TX 77029 Kingwood, TX 77339 (713) 675-8596 (281) 359-1270 (713) 675-8599 Fax (281) 359-1272 Fax District 144 District 129 Ken Legler John Davis Room E2.304, Capitol Extension Room 4S.4, Capitol Building Austin, TX 78701 Austin, TX 78701 (512) 463-0460 (512) 463-0734 (512) 463-0763 Fax (512) 479-6955 Fax 1109 Fairmont Parkway 1350 NASA Pkwy, #212 Pasadena, 77504 Houston, TX 77058 (281) 487-8818 (281) 333-1350 (713) 944-1084 (281) 335-9101 Fax District 145 District 141 Carol Alvarado Senfronia Thompson Room EXT E2.820 Room CAP 3S.06 P.O. Box 2910 P.O. Box 2910 Austin, TX 78768 Austin, TX 78768 (512) 463-0732 (512) 463-0720 (512) 463-4781 Fax (512) 463-6306 Fax 8145 Park Place, Suite 100 10527 Homestead Road Houston, TX 77017 Houston, TX (713) 633-3390 (713) 649-6563 (713) 649-6454 Fax Elected Officials in District E Texas Senate District 147 2205 Clinton Dr. -

July 2019 Whole No

Dedicated to the Study of Naval and Maritime Covers Vol. 86 No. 7 July 2019 Whole No. 1028 July 2019 IN THIS ISSUE Feature Cover From the Editor’s Desk 2 Send for Your Own Covers 2 Out of the Past 3 Calendar of Events 3 Naval News 4 President’s Message 5 The Goat Locker 6 For Beginning Members 8 West Coast Navy News 9 Norfolk Navy News 10 Chapter News 11 Fleet Week New York 2019 11 USS ARKANSAS (BB 33) 12 2019-2020 Committees 13 Pictorial Cancellations 13 USS SCAMP (SS 277) 14 One Reason Why we Collect 15 Leonhard Venne provided the feature cover for this issue of the USCS Log. His cachet marks the 75th Anniversary of Author-Ship: the D-Day Operations and the cover was cancelled at LT Herman Wouk, USNR 16 Williamsburg, Virginia on 6 JUN 2019. USS NEW MEXICO (BB 40) 17 Story Behind the Cover… 18 Ships Named After USN and USMC Aviators 21 Fantail Forum –Part 8 22 The Chesapeake Raider 24 The Joy of Collecting 27 Auctions 28 Covers for Sale 30 Classified Ads 31 Secretary’s Report 32 Page 2 Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log July 2019 The Universal Ship Cancellation Society, Inc., (APS From the Editor's Desk Affiliate #98), a non-profit, tax exempt corporation, founded in 1932, promotes the study of the history of ships, their postal Midyear and operations at this end seem to markings and postal documentation of events involving the U.S. be back to normal as far as the Log is Navy and other maritime organizations of the world. -

Primer Financing the Judiciary in Texas 2016

3140_Judiciary Primer_2016_cover.ai 1 8/29/2016 7:34:30 AM LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD Financing the Judiciary in Texas Legislative Primer SUBMITTED TO THE 85TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD STAFF SEPTEMBER 2016 Financing the Judiciary in Texas Legislative Primer SUBMITTED TO THE 85TH LEGISLATURE FIFTH EDITION LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD STAFF SEPTEMBER 2016 CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................1 State Funding for Appellate Court Operations ...........................................................................13 State Funding for Trial Courts ....................................................................................................21 State Funding for Prosecutor Salaries And Payments ................................................................29 State Funding for Other Judiciary Programs ..............................................................................35 Court-Generated State Revenue Sources ....................................................................................47 Appendix A: District Court Performance Measures, Clearance Rates, and Backlog Index from September 1, 2014, to August 31, 2015 ....................................................................................59 Appendix B: Frequently Asked Questions .................................................................................67 Appendix C: Glossary ...............................................................................................................71 -

Child Protection Court of South Texas Court #1, 6Th Administrative Judicial

Child Protection Court of South Texas Court #1, 6th Administrative Judicial Region Kendall County Courthouse 201 East San Antonio Street, Suite 224 Boerne, TX 78006 phone: 830.249.9343 fax: 830.249.9335 Cathy Morris, Associate Judge Sharra Cantu, Court Coordinator. [email protected] East Texas Cluster Court Court #2, 2nd Administrative Judicial Region 301 N. Thompson Suite 102 Conroe, Texas 77301 phone: 409.538.8176 fax: 936.538.8167 Jerry Winfree, Assigned Judge (Montgomery) John Delaney, Assigned Judge (Brazos) P.K. Reiter, Assigned Judge (Grimes, Leon, Madison) Cheryl Wallingford, Court Coordinator. [email protected] (Montgomery) Tracy Conroy, Court Coordinator. [email protected] (Brazos, Grimes, Leon, Madison) Child Protection Court of the Rio Grande Valley West Court #3, 5th Administrative Judicial Region P.O. Box 1356 (100 E. Cano, 2nd Fl.) Edinburg, Texas 78540 phone: 956.318.2672 fax: 956.381.1950 Carlos Villalon, Jr., Associate Judge Delilah Alvarez, Court Coordinator. [email protected] Information current as of 06/16. Page 1 Child Protection Court of Central Texas Court #4, 3rd Administrative Judicial Region 150 N. Seguin, Suite 317 New Braunfels, Texas 78130 phone: 830.221.1197 fax: 830.608.8210 Melissa McClenahan, Associate Judge Karen Cortez, Court Coordinator. [email protected] 4th & 5th Administrative Judicial Regions Cluster Court Court #5, 4th & 5th Administrative Judicial Regions Webb County Justice Center 1110 Victoria St., Suite 105 Laredo, Texas 78040 phone: 956.523.4231 fax: 956.523.5039 alt. fax: 956.523.8055 Selina Mireles, Associate Judge Gabriela Magnon Salinas, Court Coordinator. [email protected] Northeast Texas Child Protection Court No. -

Center for Pacific War Studies Fredericksburg, Texas an Interview

THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE PACIFIC WAR (ADMIRAL NIMITZ MUSEUM) Center for Pacific War Studies Fredericksburg, Texas An Interview with James B. Brown Orange Grove, Texas May 7, 2004 USS Zeilan, APA-3 My name is Richard Misenhimer and today is May 7, 2004. 1 am interviewing Mi. James B. Brown at his home at 346 County Road 315, Orange Grove, Texas 78372. His phone number is area code 361-384-3166. This interview is in support of the National Museum of Pacific War, Center for Pacific War Studies, for the preservation of historical infonnation related to World War II. Mr. Misenhimer Mr. Brown, I want to thank you for taking time to do this interview today. Mr. Brown Thank you. Mr. Misenhimer Let me ask you first, what is your birth date? Mr. Brown July 16, 1923. Mr. Misenhimer Where were you born? Mr. Brown Yoakum, Texas. Mr. Misenhimer Did you have brothers and sisters? Mr. Brown Yes. I have two half-brothers and two sisters and one brother. Mr. Misenhimer Were either of your brothers in the service? Mr. Brown Yes. Joe was; my real brother. One of the others was in the service in Germany. My brother was in Germany. He got captured in France and then they hauled him to Germany. But he got liberated and came back. Mr. Misenhimer Did both of them come home? Mr. Brown Yes they came home. They were lucky. Mr. Misenhimer Where did you go to high school? Mr. Brown I didn’t go to high school. I went through the fifth grade. -

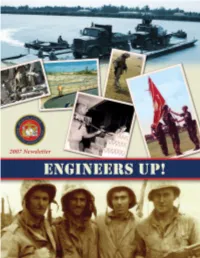

USMC and MCEA Sources) of Joint Service Cooperation

Page 4 President’s Report Page 5 Administrative Notes Page 6 Honor Roll of Deceased Members Page 7 Medal of Honor Recipients Page 12 Listing and Biographies of Senior Engineer Leaders Page 22 MCEA Memoirs from Members Page 24 MCEA Meeting Minutes Page 38 Assistance Fund Information Page 39 2006 Award Recipients Page 41 2006 Reunion Photographic Memories Page 44 Engineer Units and Organizations Cover Photo: A montage of images representative of 2007 MCEA Newsletter was prepared by the Editor, Army Marine Corps Engineers in action from World War Two Engineer Magazine under contract to MCEA, and in the spirit forward. (Photos from USMC and MCEA sources) of joint service cooperation. Contact is [email protected]. Page 2 2007 MCEA Newsletter Elected Officials: President/Secretary: Ken Frantz, Col, USMC (Ret) Vice President: Hank Rudge, Col, USMC (Ret) 1st Vice President: Charles Koenig, SgtMaj, USMC (Ret) Treasurer: Mike Ellzey, Capt (Vet) Chaplain: Pastor Stephen Robinson, MSgt, USMC (Ret) Historian: Herb Renner, MCPO, USN (Ret) Sgt at Arms: Vacant Appointments: Executive Director: George R. Hillebrand, MGySgt, USMC (Ret) Permanent Associate Directors: Jim Marapoti, Col, USMC (Ret) Jim Echols, Capt USMC (Ret) Terence J. Scully, CWO2, USMC (Ret) Charles G. Koenig, SgtMaj, USMC (Ret) Associate Directors: NAME TITLE STATE EMAIL COY, JUDY MRS VT YES NESTVED, EARL MR NY YES REYNOLDS, PAUL C MSGT TN YES SANDLIN, ROBERT E CWO3 SC YES SHORES, GEORGE W MR WI NO SMITH, DONALD C MR FL NO If you would like to be an Associate Director for your area, contact Ken Frantz Engineers Up! Page 3 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Greetings to one & all! We sincerely hope that all of you are doing better now that we have survived yet another dire winter.