Assemblies of Hierarchs and Conferences of Bishops: a Comparative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dopady Různosti Obřadů V Manželských Kauzách Na Církevním Soudu

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE KATOLICKÁ TEOLOGICKÁ FAKULTA Miloš Szabo Dopady různosti obřadů v manželských kauzách na církevním soudu Disertační práce Vedoucí práce: prof. JUDr. Antonín Hrdina, DrSc. 2014 Prohlášení 1. Prohlašuji, že jsem předkládanou práci zpracoval samostatně a použil jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. 2. Prohlašuji, že práce nebyla využita k získání jiného titulu. 3. Souhlasím s tím, aby práce byla zpřístupněna pro studijní a výzkumné účely. V Praze dne 25. 11. 2014 2 Bibliografická citace Dopady různosti obřadů v manželských kauzách na církevním soudu [rukopis]: disertační práce / Miloš Szabo; vedoucí práce: Antonín Hrdina. – Praha, 2014. – 187 s. (+ 74 s. příloha) Anotace Křesťanství se z Jeruzaléma šířilo několika směry. Jedno z jeho nejvlivnějších center vzniklo v Římě, jenž se stal také sídlem papežů a zůstal jím i po přesídlení císaře do tehdy řecké Konstantinopole. Kromě Říma, spjatého s apoštolem Petrem však existovaly i další velké křesťanské obce, založené ostatními apoštoly, ležící na východ od římské říše, které se stejně jako ta římská nazývaly církví. A tak i dnes kromě největší latinské (římské) církve existují desítky východních, právem se chlubících vlastní apoštolskou tradicí. V průběhu dějin došlo několikrát k narušení jejich komunikace s Římem, ale i mezi sebou navzájem. V dnešní době, kdy z různých důvodů dochází k velkým migračním vlnám, se některá církevní společenství, doposud považována striktně za východní, dostávají do diaspory s latinskou církví, čímž vzniká nejen velká pravděpodobnost růstu počtu smíšených intereklesiálních manželství, ale zároveň také zvýšené množství manželských kauz, které bude muset následně řešit církevní soud. Aby jeho rozhodnutí bylo spravedlivé, je potřebné znát jak historii těchto východních církví, mezi nimiž je i dvacet dva sjednocených s Římem (tedy východní katolické církve), tak i především jejich teologická specifika, spiritualitu a partikulární právo. -

Ecclesiastical Circumscriptions and Their Relationship with the Diocesan Bishop

CANON 294 ECCLESIASTICAL CIRCUMSCRIPTIONS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE DIOCESAN BISHOP What is the relationship of the faithful in personal ecclesiastical circumscriptions to the local diocesan bishop? OPINION The Apostolic See, in the Annual General Statistical Questionnaire, asks diocesan bishops the number of priests in the ecclesiastical circumscription of the diocese, their country of origin and whether they are diocesan or religious. The fact that the diocesan bishop is answering these questions indicates the close relationship between himself and any personal Ecclesiastical Circumscription. Canons 215 and 216 of the 1917 Code required that ecclesiastical circumscriptions be territorial within a diocese and an apostolic indult was needed, for example, to establish personal parishes for an ethnic group of the faithful. After World War II, Pope Pius XII provided for the pastoral care of refugees and migrants in his apostolic constitution Exsul Familia in 1952. Chaplains for migrants were granted special faculties to facilitate pastoral care without receiving the power of jurisdiction or governance. The Second Vatican Council admitted personal criteria in ecclesiastical organisation. The decree Christus Dominus 11 held that the essential element of a particular Church is personal, being a “portion of the people of God”. Personal factors are crucial to determine the communitarian aspect of the makeup of a community. After Vatican II, the Code of Canon Law needed revision. The Synod of Bishops in 1967 approved the principles to guide the revision of the code. The eighth principle stated: “The principle of territoriality in the exercise of ecclesiastical government is to be revised somewhat, for contemporary apostolic factors seem to recommend personal jurisdictional units. -

Parish Pastoral Council Guidelines

PARISH PASTORAL COUNCIL GUIDELINES “Building up the Community of Believers” Archeparchy of Winnipeg 2007 ARCHEPARCHY OF WINNIPEG PARISH PASTORAL COUNCIL GUIDELINES I. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 1 1. Origin ................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Nature................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Pastoral Character............................................................................................................ 4 4. Pastoral Reflection............................................................................................................ 5 II. CHARACTERISTICS...................................................................................................... 6 1. Membership....................................................................................................................... 6 2. Leadership ......................................................................................................................... 8 3. Executive.......................................................................................................................... 10 4. Committees ...................................................................................................................... 11 5. Meetings.......................................................................................................................... -

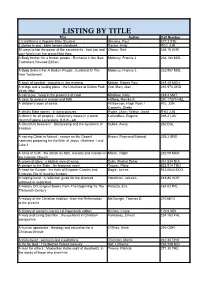

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

Brief of Appellee, Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Virginia

Record No. 120919 In the Supreme Court of Virginia The Falls Church (also known as The Church at the Falls – The Falls Church), Defendant-Appellant, v. The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America and The Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Virginia, Plaintiffs-Appellees. BRIEF OF APPELLEE PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN THE DIOCESE OF VIRGINIA Bradfute W. Davenport, Jr. (VSB #12848) Mary C. Zinsner (VSB #31397) [email protected] [email protected] George A. Somerville (VSB #22419) Troutman Sanders LLP [email protected] 1660 International Drive, Suite 600 Troutman Sanders LLP McLean, Virginia 22102 P.O. Box 1122 (703) 734-4334 (telephone) Richmond, Virginia 23218-1122 (703 734-4340 (facsimile) (804) 697-1291 (telephone) (804) 697-1339 (facsimile) CONTENTS Table of Authorities .................................................................................... iiii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Facts ........................................................................................................... 2 Assignment of Cross-Error .......................................................................... 5 Argument .................................................................................................... 5 Standard of Review ........................................................................... 5 I. The Circuit Court correctly followed and applied this Court’s -

September 2015 Issue Of

Eastern Catholic Life Official Publication of the Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Passaic VOL. LI, NO. 9 SEPTEMBER 2015 In Line With Vatican II: New Rules on Eastern Married Clergy by Archbishop Cyril Vasil’, SJ, with Bishop George Gallaro INTRODUCTION The November 2013 Plenary Session of the Congregation for the Eastern Churches, among other things, adequately dealt with this issue and reached ntil recently, it seemed that the presence and ministry of Eastern the wide-ranging consent of the members present. As a consequence, the UCatholic married clergy in the so-called diaspora (places outside of Prefect of the Eastern Congregation submitted to the Holy Father, Pope the traditional territories) was a closed question. In fact, not much could Francis, the request to grant, under certain conditions, to the respective ec- have been added to its historical or canonical viewpoint that had not al- clesiastical authorities the faculty to allow Eastern Catholic married clergy ready been studiously examined. The issue is summarized by the 1990Code to minister even outside of their traditional territories. of Canons of the Eastern Churches: “The particular law of each Church sui iuris or special norms established by the Holy See are to be followed in ad- The Holy Father, at the audience granted to the Prefect of the Congrega- mitting married men to sacred orders” (Canon 758, paragraph 3). tion for the Eastern Churches, Cardinal Leonardo Sandri, on December 23, 2013, favorably received this request, notwithstanding the least things to Following ancient discipline, all Eastern Catholic Churches – with the the contrary (contrariis quibuslibet minime obstantibus) and the text of the exception of the Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara Churches [of India - new norms was published on June 14, 2014. -

RAPID CITY PMD 2019 Conference One

RAPID CITY PMD 2019 Conference One RECONCILE DIFFERENCES UNITE MISSION AND COMMUNION CONFIRM THE HOLY SPIRIT, CONTINUE HEALING, SUSTAIN LIFE-TIME COMMITTMENT Purpose Model Principles IF ANY MODEL OF LEADERSHIP DOESN’T WORK AS THE CHURCH HERSELF WORKS, IT WON’T WORK MISSION DIOCESE TO A DIOCESE WITH A MISSION TOP TEN • 1. Post-conciliar models of consultation • 2. • 3. as it relates to the structure and • 4. governance of parishes within the • 5. diocese and the implementation of • 6. • 7. the vison and purpose of the • 8. diocesan pastoral plan. • 9. • 10. committees and meetings Fundamental Theology Fundamental Anthropology 50 Parish Finance Council Council Liturgy Committee Stewardship Committee Community Building Life Committee Committee STANDARDIZED NAMES DEFINITIONS ROLES RESPONSIBILITIES FOUNDATIONSacred Scripture PRINCIPLES EPHESUS EPHESUS EPHESUS Establishment of structure, governance and authority in the Cathoic Church Information from the field informs an forms There is a Head There is a Body Those who discuss Those who decide Pope (St. Peter) HEADS Bishop (Apostles) (mission field) Pastor BODY Faith Pope – College of Bishops Bishop – Consultors, Presbyteral Council, Staff Pastors – Parish Councils, Finance Councils, family, friends, etc. Head Body offers makes information decision to decision maker ARRRGG! Majority rule Executive privilege Head Body makes decision makes sure the decision is best for the head and the body authority wisdom UNITED ONE HOLY CATHOLIC APOSTOLIC Heaven Already Heaven yet not Heaven Temporal Mystical Mystical Temporal Vertical Vertical Horizontal Hierarchical+++++++++++ **Relat onal ** Fundamentally Foundationally anthropological theological Corporate Corporeal CIVIL LAW CANON LAW Blur effective consultation, collaboration & consensus Abruptly end consultation with hard words of law & authority Head DecidesAdvises Body CONSULTATION IS ABOUT THE MISSION OF THE CHURCH CONSULTATION The people of God have a right to full and active participation in the mission of the Jesus Christ through the ministry of the Church. -

The Diocese of Minsk, Its Origin, Extent and Hierarchy

177 The Diocese of Minsk, its Origin, Extent and Hierarchy BY Č. SIPOVIČ I Those who would wish to study the history of Christianity in Byelorussia should certainly pursue the history of the Orthodox and Catholic churches, and to a lesser extent, that of various groups of Protestants. One must bear in mind that the Catholic Church in Byelorussia followed and still follows two Rites: the Latin and the Oriental-Byzantine. It is acceptable to call the latter by the name Uniate. In Byelorussia it dates back to the Synod of Brest-Litoŭsk in the year 1596. But here we propose to deal exclusively with the Catholic Church of the Latin Rite, and will further limit ourselves to a small section of its history, namely the foundation of the diocese of Minsk. Something also will be said of its bishops and admin istrators. Exactly how and when the Latin form of Catholicism came to Byelorussia is a question which has not been sufficiently elucidated. Here then are the basic historical facts. From the beginning of the acceptance of Christianity in Byelo russia until the end of the 14th century, the population followed the Eastern Rite and until the end of the 12th century it formed part of the universal Christian Church. After the erection of a Latin bishopric in Vilna in 1387, and after the acceptance of Christianity in the Latin Rite by the Lithuanians, this episcopal see itself and its clergy started to propagate this rite. It is well-known that Jahajła had virtually the same relations with the pagan Lithuanians as with Orthodox Ukrainians and Byelo russians. -

The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 12 Issue 2 Article 4 3-1992 The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania Emmerich András Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion, Toronto Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation András, Emmerich (1992) "The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol12/iss2/4 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW ORGANIZATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN ROMANIA by Emmerich Andras Dr. Emmerich Andras (Roman Catholic) is a priest and the director of the Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion in Vienna. He is a member of the Board of Advisory Editors of OPREE and a frequent previous contributor. I. The Demand of Catholics in Transylvania for Their Own Church Province Since the fall of the Ceausescu regime, the 1948 Prohibition of the Greek Catholic Church in Romania has been lifted. The Roman Catholic Church, which had been until then tolerated outside of the law, has likewise obtained legal status. During the years of suppression, the Church had to struggle to maintain its very existence; now it is once again able to carry out freely its pastoral duties. -

During Trip to Indianapolis, Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem Speaks Of

Inside Respect Life Sunday Archdiocese honors pro-life supporters for their service, page 3. See related column, page 4. Serving the ChurchCriterion in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com October 5, 2012 Vol. LIII, No. 1 75¢ New world Photo by Sean Gallagher evangelization: Synod’s agenda includes America VATICAN CITY (CNS)—When Blessed John Paul II launched the project he called the new evangelization, he made it clear that it was aimed above all at reviving the ancient faith of an increasingly faithless West—“countries and nations where religion and the Christian life were formerly flourishing,” now menaced by a “constant spreading of religious indifference, secularism and atheism.” Those words are commonly taken to refer to Christianity’s traditional heartland, Europe. Yet, Pope Benedict XVI, who has enthusiastically embraced his predecessor’s initiative, has made it clear that the new evangelization extends to other secular Western societies, Patriarch Fouad Twal greets Lumen Christi Catholic School students on Sept. 28 on the steps of Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary Church in Indianapolis including the United after celebrating Mass with them. Patriarch Twal, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, visited Indianapolis for a meeting of the Equestrian Order of the States. Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, an international Catholic organization that supports the Church in Cyprus, Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian territories. Pope Benedict XVI In a series of speeches to visiting U.S. bishops last fall and earlier this year, During trip to Indianapolis, Latin Patriarch of Pope Benedict reflected on the “spiritual and cultural challenges of the new evangelization,” Jerusalem speaks of hope for the Holy Land giving special emphasis to a “radical secularism” that he said has worn away By Sean Gallagher 1,000 years, is today made up of clergy and was an appeal to the politicians to do their America’s traditional moral consensus and lay Catholic men and women from around best to stop this war.” threatened its religious freedom. -

Legalization of Greek Catholic Church in Czechoslovakia in 1968

E-Theologos, Vol. 1, No. 2 DOI 10.2478/v10154-010-0017-3 Legalization of Greek Catholic Church in Czechoslovakia in 1968 Jaroslav Coranič University of Prešov in Prešov, Faculty of Greek-Catholic Theology A re-legalization of the Greek Catholic Church in Czechoslovakia was one of the most important results of the revival of socio - political process of the Prague Spring. This Church, unlike the Roman Catholic Church in the period 1950 - 1968 did not even exist legally. It was due to power interference of the communist state power in 1950. The plan of Commu- nist Party assumed the "transformation" of Greek Catholic Church into the Orthodox one. Procedure of liquidation of the Greek Catholic Church later came to be known as Action "P". Its climax came in April 28th 1950, when “sobor of Presov”, being prepared for a longer time, took place. The gath- ering in “sobor” manipulated by the communists declared in “sobor” the abolition of the Union with the Vatican, as a result the Greek Catholic Church ceased exist in Czechoslovakia and the clergy and faithful were meant to became the members of the Orthodox Church.1 In fact only a small part of the Greek Catholic clergy succumbed to power pressure and accepted Orthodoxy. Church leaders, as well as many priests who refused to change to the Orthodox have been arrested and sentenced to many years of punishment. The other Greek-Catholic clergy and their families were deported to the Czech lands and were forbidden to perform a duty of priestly ministry and banned from staying in eastern Slovakia for several years. -

Pope Says Suffering Reveals Humanity Can Change People for the Better

Pope says suffering reveals humanity can change people for the better AMMAN, Jordan – Pope Benedict XVI’s first stop in Jordan was at a church-run facility for people with disabilities, a place he said demonstrates how suffering can change people for the better. “Standing in your midst, I draw strength from God,” the pope told the clients of Amman’s Regina Pacis center, established in 2004 by the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Arriving directly from the Amman airport May 8, the pope said that “in our own trials, and standing alongside others in their struggles, we glimpse the essence of our humanity; we become, as it were, more human.” “And we come to learn that, on another plane, even hearts hardened by cynicism or injustice or unwillingness to forgive are never beyond the reach of God,” because every heart “can always be opened to a new way of being, a vision of peace.” The center is operated by three Comboni Missionary Sisters and a team of teachers, therapists and volunteers to educate and care for Muslims and Christians with disabilities. With a particular mission to the poor, it provides vocational training, therapy and basic medical care free of charge. Satellite centers operate in six other Jordanian cities. The pope told the clients and workers, “At times it is difficult to find a reason for what appears only as an obstacle to be overcome or even as a pain – physical or emotional – to be endured. “Yet faith and understanding help us to see a horizon beyond our own selves in order to imagine life as God does.