What Is Clear from These Statistics Is That Even Within South Africa's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 The Invisible Migrants There have, however, been several short articles on exiled and other South Africans in Britain which have appeared in journals and news papers such as Race Today, New Society, Third World, the Guardian and the Independent on Sunday (Kozonguizi, 1969; Lapping, 1969; de Gier, 1987; Cunningham, 1988). 2 Apart from the plethora of autobiographies and two Hollywood films (Cry Freedom and A World Apart), a series of interviews with South African exiles appeared in the British press: with Hugh Masekela (Johnson, 1990), Peter Hain (Keating, 1991) and articles on South Africans in Britain by Freedberg (1990), Sher (1991) and Fathers (1992) . In addition, Anthony Sher appeared in a film written by Alan Cubitt for 'Screen Play' on BBC2, The Land of Dreams (transmitted 8 August 1990), and Christopher Hope (1990) presented a Kaleido scope programme on exile for Radio Four (transmitted 16 February 1990). 3 There have, of course, been exceptions. In a book published in 1994, Robin Cohen traced the relationship between Britain and Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa and Rhodesia (Cohen, 1994). 4 None of these archives have been fully catalogued. Indeed, the mate rial in the IDAF and AAM collections will not be easily accessible for several more years. 5 The choice of 75 interviews seemed a reasonable compromise between my desire to obtain detailed accounts and a series of resource and time constraints. The sample size was chosen to give me enough information to study exiles as individuals as well as enough people to be able to consider what was going on among other exile groupings. -

Engine for Snbs

^ "■ ■<'' , ij. 1 • - FRIDTHT, JUNE IS, 1962 Average Daily Net Preaa Run PAGE TWENTY •The Weather*; 5 V For the Week Endtag lianrljfB tfr lEvcuiitg % ral& June T, 1982 FoNCMt el V. ■. Weather 1 Mre. jalikes H. McVeigh of 81 10,596 Fair tonight, Sunday..! Osfard .9traet> ehalew cioncniiraSf iiivui ciuuij^ UT" AbotrtT<ny»^ jCOiAmlttee In charge of the Km- clal meeting for Tuesday, June IT, M em ber of the Audit blem’/Club’a 26th anniversary cele at 8 p. m.- Important matters of . ^ Bureau of CIrculatlone , V perahire. - I 5 ; Word WM recelvtd yMterdky of bration; and . Mrs. Helen Qrlfrin business are on the agenda and Civic Projects Opens Sunday Mancke»ter— A City of Village Charm --------- n the promotion of Robert A. Geg- of 93 Scarborough road, urge all every member is urged to attend. non to the rank of corporal in the club members and IClka who plan ------------- ------------------- Air l'‘orce. Corp, Otgnon e n te i^ to attend and have not already Manchester Orange will neigh Funds irpro -Lions Club Late Start Caused VOL. LXXI, NO. 218 (ClaaeUled AdvertUlng on Page 10) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, JUNE 14, 1952 k LVE PAGES) PRICE n V B ,r C l8 M I the eervlce In November,'ISSI, rfd sent In 'thair^ reaervatlona for -tho bor- with- Thompson -Grange- Tues ie atatloned at Nellie Air Force dinner, Sunday at 5:30 at the car day night and furnish a part of Hors<t siiow Will Go In Rain Which Delayed eiflCKltONi Baee, Lae Vegae, Nev. He |« the riage house, Maxwell Court, to do the program. -

13 December 1985.Pdf

No16 mherpricesonpage2 R2 ·000 ·for surrendering ~ Inside . The 'A-Tealll' fails S4RRENDERED Swapo insurgent, Martin Amakali, pictured outside the Tintenpalast after announcing in rescue bid - Inside his)intention to 'join the army'. Ka angula fights for political life STAFF REPORTER THE STAGE has been set for next Tuesday when the Chairman of the largest ethnic administration, Mr Peter Kalangula, will fight the biggest battle for political sur vival in his career. In terms of an out-of~court settle ment this week, a brief extraordinary session of the Ovambo Legislative Assembly has to be convened on that day to reconsider the R128-million budget of the administration. Political forces of Etango and the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA) are combining in a concerted effort to oust Mr Kalangula and take the Ovambo-speaking community into the in terim government. Continued on page 2 Anglicans buy farm of former TeL chief STAFF REPORTER _ THE ANGLICAN Church has Diocesan Secretary, Mr Matt bought the farm of the former Esau, confirmed that the proper THE FARM ASIS, near Kombat, bought by the Anglican Church from former TCl General Manager, Mr General Manager of Tsumeb ty of 3531 hectares, and located Jim Ratledge. Corporation Limited, Mr Jim five kilometres south of Kombat, Ratledge, in the Kombat district, Continued on page 2 for R 736857. we help you SATURDAY OShOO~3hOO to do your 16hOO-1Sh30 xmas shopping SUNDAY 10hOO-12h30 :~ at leisure 16hOO-18h30 ~ " 'with our 1rV'-....."i ONLY 11 SHOPPING DAYS ... ___- .--.. .._.- ...... " . ' \. {~ ~ lJ shopping hours TO CHRISTMAS! ,~\.. .' Come and lOin our Xmas ) . -

Capitalist Expansion

A Dialectic of Talking Forests: Trotskyist Ecology Through Afghan Sufi Cosmology Bilal Zenab Ahmed (SOAS, University of London (PhD)) This paper argues that a Trotskyist understanding of dialectics is well-suited to be combined with a few different intellectual mechanisms present in Pashto literature, oral storytelling, and Naqshbandi Sufi cosmology, to pursue a properly Marxist understanding of ecology and climate change. Such a model of understanding is highly appropriate to the local context of Northwest Pakistan and Southern Afghanistan, and can also potentially inspire new forms of dialectical understanding, elsewhere.I focus on the Afghan poet and refugee Pir Muhammad Karwan, who wrote a collection of work about the Soviet-Afghan War while living in Pakistani refugee camps during Taliban rule in the 1990s. Karwans poetry can be roughly classified as neoplatonist, due to its reliance on local Sufi concepts like maanavi and the imaginal plane. Perso-Arabic Sufi cosmology enables Karwan to work through an intellectual matrix that both abolishes and retools concepts like the self and other, technology and organic beings, human and nonhuman species, living and nonliving objects, embodied and cognitive knowledge, and sentient and non sentient natural processes. This is clear from works like The Chinar Tree Speaks, which discusses the Soviet-Afghan war from the perspective of human and tree, and The Talking Forest, which goes further to describe a forest not just in terms of its material content, but as a network of physical and emotional processes that feels, thinks, and speaks in its own spoken and embodied language.While Karwan is explicitly discussing the Soviet-Afghan War, its possible to use his perspective as a springboard for discussing the various impacts and processes involved in climate change. -

West Ministers Agree on Summit

4 .,. ' / '■ -'^ . ■■ /:.■ . ' 'T h fl Wwthcr' " * / 9- . WEDNESDAY, APRIL 18, I860 Average Daily Net PreM Ron Feraiaant of U. B W anitef 'Umsoag r PA€E TWENTY-EIGHT For tho WMk Ended - " ■ 'I .:- liattflii^ater lEufttittg Iggratt April t, IMO Fair and w am tonight ahd fM -' . ' >v'^ ’:5 day. IMW tsniflbt M ar M . B|gk for th* sale may ca ll-W s. -U l- returned home after spending the The senior choir of the Salva 13,095 Friday In Mb. Dale Brown, a graduate of Man- tion Army will sponsor its annual llan Perrett, 49 Keeney S t cheater High School, haa been winter in S t Petersburg, and Member at the Audit A b o u t T ow n Gulfport Fla. Food Sale Saturday'at »:80 a.m. in Boreaa of CNrenlatlon M anche»ter-^A City o f Village Charm elected treasurer of the new stu the vestibule of the church. Mrs. The F ^ s Keynolds Group of Hale’s Self Siene anil Meat Detit dent government at High Point Frank Duncan and Miss Olatos Second Congregational' Church College, High Point N. C. The -midweek service at ' the will meet tomorrow at 10 a.m. in Sam Y uIjtm, M Florence S t, Is Church of the Nazareno will be White are co-chairmen of the sale, ») Pjj^CB FIV E dtolTB ■pending ■ tw6 weeks' vacation In which will offer a variety of c^es, Hie church parlors. Hostesses will MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, APRIL 14, 1960 John Munsle, 829 Main St. held tomorrow at 7:80 p.m. -

Reflections on the State of International Relations in South Africa

National Office-Bearers/Nasionale Ampsdraers Chairman/Voorsitter Dr C B Strauss Deputy Chairmen/Ad/unk- Voorsitters Gideon Roos Gibson Thula Hon. Treasurer/Ere-Te&ourier Elisabeth Bradley Hon. Legal Advlser/Ere-Regsadvlseur ALBostOCk Dlreetor-General/Direkteur-Generaal John Barratt Editorial Advisory Board Professor James Barber Pro-Vice Chancellor, University of Durham, England Professor John Dugard Head of Centre for Applied Legal Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Professor Deon Geldenhuys Head of Department of Political Science. Rand Afrikaans University, Johannesburg Professor WFSuttendge Executive Oirector Research Institute for the Study of Conflict and Terrorism London, England Mrs Helen Kitchen Director of African Studies, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Georgetown University, Washington DrWinnchKuhne Head of Africa Dept, Sliftung Wissenschaft und Politik, D-8026 Ebenhausen, West Germany Professor Gavin fvtaasdorp Director, Economic Research Unit, University of Natal, Durban Professor JohnMarcum University of California (Santa Cruz) Professor Robert Schnre Director, Institute for the Study of Public Policy University of Cape Town ProfessorJESpence Head ol Dept of Political Studies, University of Leicester, England Professor Peter Vale Centrefor Southern African Studies, University ol Western Cape, Bellville International Affairs Bulletin Published by the South African Institute of International Affairs at Jan Smuts House, PD Box 31596, Braamfontem 2017, South Africa and supplied free of charge -

Jdl Vol 4 No 1

Journal for Development and Leadership 1 2 Journal for Development and Leadership JOURNAL FOR DEVELOPMENT AND LEADERSHIP (JDL) Faculty of Business and Economic Sciences Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Port Elizabeth Eastern Cape, South Africa Tel: +27(41) 504 4607I2906 Electronic Mail: [email protected] [email protected] Web Address: http://jdl.nmmu.ac.za EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Editor-in-chief and Chairperson of the Editorial Committee Prof. H.R. Lloyd Managing Editor Prof. R. Haines Consulting Editor: Academic Standards Prof. C.V.R. Wait Consulting Editors: Future Studies Prof. K. Jonker Prof. C. Adendorff Consulting Editor: Ethics Prof. C. Rootman Consulting Editors: Management Sciences Prof. M. Tait Prof. E. Venter Consulting Editors: Industrial Psychology and Human Dr M. Mey Resources Management Prof. R. van Niekerk ConsultingEditor: Business School Prof. C. Arnolds Consulting Editors: Economics, Development and Tourism Prof. P. le Roux Prof. R. Ncwadi Prof. J. Cherry Mr H.H. Bartis Consulting Editors: Accountancy Prof. H. Fourie Editorial Co-ordinator Prof. I.W. Ferreira Administrative and Logistics Co-ordinator Mrs R. Petrakis Journal for Development and Leadership 3 JOURNAL FOR DEVELOPMENT AND LEADERSHIP Faculty of Business and Economic Sciences Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Volume 4, Number 1, June 2015 Journal for Development and Leadership First Publication 2012 ©Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University ISSN: 2226-0102 Printed and bound by: Bukani Print, Port Elizabeth, South Africa 4 Journal for Development and Leadership NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD SURNAME AND TITLE AFFILIATION CONTACT DETAILS INITIALS Prof Allais, C. University of South Africa (UNISA) [email protected] Prof Allegrini, M. -

Witness Seminars Pretoria

King’s Research Portal Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kandiah, M. D., & Glencross, M. P. (2014). South Africa Witness Seminars: The History, Role and Functions of the British Embassy/High Commision in South Africa, 1987-2013; Britain & South Africa, 1985-91. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Jv 12 Sechaba April Issue 1985

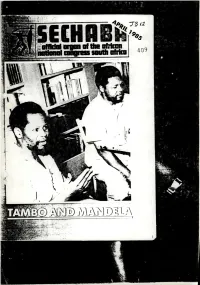

-JV 12 SECHABA APRIL ISSUE 1985 CONTENTS: EDITORIAL Forward lo the Year of the Cadre and the People’s Parliament........................................1 MANDELA’S REPLY TO BOTHA "Your freedom and mine cannot be separated. I will return." ........................................2 WARMONGERS WHO TALK OF PEACE United Suites Strategy in Southern Africa, by Brian Bunting..........................................6 ANC INTERNATIONAL........................................................................................14 RESPONSE TO COMRADE MZALA By Nyawuza.........................................................................................................................18 PREPARING THE FIRE BEFORE COOKING THE RICE INSIDE THE POT Some Burning Questions of Our Revolution, by Alex Mashinini..................................20 BOOK REVIEW............................................................................................31 POEM The Road to Freedom, by Freddy Reddy......................................................................... 32 Annual Subscriptions: USA and Canada (air mail only) 512.00 Elsewhere £6.00 Single Copies: USA and Canada (air mail only) S 3.00 Elsewhere £0.50 Send your subscriptions to: Sechaba Publications P.O. B«>\ 38. 28 Penton Street, London M 9PR United Kingdom Telephone: 01-837 2012 lelex: 29955ANCSAG Telegrams: Mayibuye Donations welcome. Our from cover shows a picture taken in the early sixties of two leaders of the ANC, Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela. Our back cover shows Albertina Sisulu, one of the -

JBMD Part2 PAGE: 1 SESS: 47 OUTPUT: Thu Feb 19 09:46:35 2009 /Dtp22/Juta/Academic/JBMD−08Part3/000Prelims

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320347354 The Relationship between Employer of Choice Status and Employer Branding Article · December 2008 CITATIONS READS 2 68 2 authors, including: Snyman Ohlhoff Cape Peninsula University of Technology 10 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: 1st TESA International Conference View project KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2008 View project All content following this page was uploaded by Snyman Ohlhoff on 18 October 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. JOBNAME: JBMD Part2 PAGE: 1 SESS: 47 OUTPUT: Thu Feb 19 09:46:35 2009 /dtp22/juta/academic/JBMD−08part3/000prelims JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT DYNAMICS (JBMD) Faculty of Business Cape Peninsula University of Technology Volume 2 No 2 December 2008 JOBNAME: JBMD Part2 PAGE: 2 SESS: 41 OUTPUT: Thu Feb 19 09:46:35 2009 /dtp22/juta/academic/JBMD−08part3/000prelims Journal of Business and Management Dynamics First published 2008 Juta & Company Ltd Mercury Crescent, Wetton, Cape Town, South Africa © 2008 Cape Peninsula University of Technology ISSN No: 2070-0156 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Subject to any applicable licensing terms and conditions in the case of electronically supplied publications, a person may engage in fair dealing with a copy of this publication for his or her personal or private use, or his or her research or private study. -

Democratic Nation-Building in South Africa. INSTITUTION Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria (South

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 214 SO 026 993 AUTHOR Rhoodie, Nic, Ed.; Liebenberg, Ian, Ed. TITLE Democratic Nation-Building in South Africa. INSTITUTION Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria (South Africa) . REPORT NO ISBN-0-7969-1575-X PUB DATE 94 NOTE 470p. AVAILABLE FROMHuman Sciences Research Council, 134 Pretorius Street, Pretoria 0002, South Africa. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Change Strategies; Community Development; *Democracy; *Democratic Values; *Developing Nations; Foreign Countries; *Social Change; Social Values IDENTIFIERS *South Africa ABSTRACT This book is a collection of essays by 50 eminent experts/analysts representing a broad range of ideological perspectives and interest groups. Its aim is to contribute to the process of democratic nation-building and the creation of a culture of tolerance by educating South Africans about the intricacies of community reconciliation and nation-building. Following a section featuring information about each of the contributing authors, the book is divided into 11 sections, which are further divided into 47 chapters. The main sections are:(1) "Nation-Building as a Democratic Means of Reconciling National Unity with Ethnic and Cultural Diversity";(2) "The Role of Ethnic Nationalism in Nation-Building"; (3) "The Constitutional and Institutional Bases of Democratic Government in South Africa";(4) "The Sociopolitical Conditions for Democratic Nation-Building and Intercommunity Reconciliation"; (5) "Key Socioeconomic Determinants of Democratic Nation-Building in South Africa"; (6) "The Transition from Apartheid to Democracy"; (7) "Gender Equality as a Precondition for Democratic Nation-Building"; (8) "Violence--A Pervasive Inhibitor of Nation-Building";(9) "The Role of the Security Institutions";(10) "International Involvement in Nation-Building"; and (11) "Concluding Overview: the Prospects for Democratic Nation-Building in South Africa." (LAP) ***********************************************************AAAA::**A**A:.