Christopher Wilmarth Laura Rosenstock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHAPE-SHIFTER How Lynda Benglis Left the Bayou and Messed with with the Establishment

THE SHAPE-SHIFTER How Lynda Benglis left the bayou and messed with with the establishment BY M.H. MILLER Senior Editor You notice her face first. This is odd, because she’s nude, her body bronzed and oiled, with one wiry arm holding a large dou- ble-sided dildo between her legs. Her eyes aren’t even in play; a pair of white sunglasses covers them. The focus is really on her face, framed by an androgynous hairstyle that could have been cut and pasted from the cover of David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane. Her eyebrows are shaved. Her expression, to the extent that it’s readable, rests somewhere between a smirk and a grimace. Lynda Benglis was about to turn 33, and she wanted her nude self-portrait to run alongside a feature article about her by Robert Pincus-Witten in the November 1974 issue of Artforum. John Coplans, Artfo- rum’s editor, wouldn’t allow that, so her dealer at the time, Paula Cooper Gallery, took out an ad, which cost $2,436. Benglis paid for it, which involved a certain amount of panic. In the middle of October, as the issue was getting ready to go to the printer, she reached out to Cooper, frantically trying to track down collectors with outstanding payments so she could put the money toward the ad. “Everyone seems out to get me,” she wrote. Benglis’s ad might have been written off as a quirky footnote for an artist who would go on to become a pioneer of contemporary art in numerous guises, from video to sculpture to painting and beyond. -

Oral History Interview with Jack Whitten, 2009 December 1-3

Oral history interview with Jack Whitten, 2009 December 1-3 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Jack Whitten on 2013 December 1 and 3. The interview took place in Woodside, N.Y., and was conducted by Judith Olch Richards for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Jack Whitten and Judith Olch Richards have reviewed the transcript. Jack Whitten's corrections and emendations appear below in brackets. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JUDITH RICHARDS: This is Judith Richards interviewing Jack Whitten on December 1, 2009, at his studio in Woodside, Queens, New York, for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, disc one. Jack, I'd like to start with your family, as far back as you want to go– it could be even your grandparents, if you have information about them, and then going on to your parents and yourself and your siblings. And then we'll focus on you again. JACK WHITTEN: Yes. My mom [as] Annie B. Whitten and my father was Mose Whitten. MS. RICHARDS: Annie – A-N-N-I-E? MR. WHITTEN: A-N-N-I-E. MS. RICHARDS: And B is – MR. WHITTEN: Belle. Annie Belle. -

Richard Kalina CV 2019

LENNON, WEINBERG, INC. 514 West 25th Street, New York, NY 10001 Tel. 212 941 0012 Fax. 212 929 3265 [email protected] www.lennonweinberg.Com Richard Kalina Born: New York City, 1946 Resides and works in New York City EDUCATION 1966 University of Pennsylvania, B.A. EXHIBITIONS 2019 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC., Richard Kalina: Future Perfect, February 21-MarCh 30, 2019. 2017 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina and Roy Dowell: “Synchronicity: A State of Painting,” November 9-DeCember 23. 2016 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Panamax: New Paintings and Watercolors, February 18- MarCh 26. 2014 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina: New Paintings and Watercolors, February 20-MarCh 29. 2012 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. New Paintings and Watercolors, January 19-February 25. 2010 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina: A Survey of Works 1970-2010, June 10- August 13. 2009 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. New Paintings and Watercolors, March 26-May 2. 2006 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. New paintings and watercolors, OCtober 21 – November 27. 2003 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina: New Works, November 7 – DeCember 20. 2001 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina: New Paintings and Selected Drawings 1990- 2001, March 22 – April 21. 1998 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina, September 10 – October 10. 1995 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina: New Paintings, November 16 – DeCember 22. 1993 New York, Lennon, Weinberg, InC. Richard Kalina: New Paintings, September 30 – November 6. 1992 New York, Diane Brown Gallery. New York, Ledis Flam Gallery. 1989 New York, Elizabeth MCDonald Gallery. -

Minimalist Sculpture: the Consequences of Artifice

Minimalist Sculpture: The Consequences of Artifice. John Edward Penny Submitted in accordance with the requirements of PhD. The University of Leeds Department of Fine Art August 2002 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl,uk TEXT CUT OFF IN THE ORIGINAL Abstract. This study, "Minimalist Sculpture: The Consequences of Artifice", was initially prompted by the wish to examine the case for a materialist approach to modern sculpture. Such an inquiry needed to address not only the substantiality of material and its process, but also the formative role of ideology on those choices of governing materials and procedures. The crux of this study began as, and remains, an inquiry into physical presence, and, by extension, the idea that Minimalist sculpture somehow returns the viewer to the viewer. At the core of any materialist position is the certainty that experience contains an element of passivity. If nothing exists but matter and its movements and modifications, then consciousness and volition depend entirely on material agency. The hierarchy of such a scheme underpins the socio-economic and cultural level with that of the biological, and, in turn, the biological with the physical. However, perception is not a matter of automatically recording external stimuli, but requires active elaboration. A hermeneutic process, therefore, is not one of unbridled pure thought; rather, it requires the recognition of an external and constant measure that gives form to thought. -

Jake Berthot

JAKE BERTHOT 1939 Born in Niagara Falls, NY 1960-61 New School for Social Research, New York, NY 1960-62 Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY 1974-81 Teaches at Cooper Union, New York, NY 1982 Resident Artist, Skowhegan School, Skowhegan, ME 1982-1992 Teaches at Yale University, New Haven, CT 1993 Teaches at University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 1992-2012 Teaches at School of Visual Arts, New York, NY 2001 Visiting Artist at SUNY Ulster, Stone Ridge, NY 2014 Died in Accord, NY Solo Exhibitions 2016 Jake Berthot: In Color, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2015 Extrasensory: The Works of Jake Berthot, New York Studio School, New York, NY 2013 Jake Berthot, Paintings and Drawings, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Jake Berthot: Works on Paper, The Enamel Drawings, John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY 2012 Jake Berthot, Drawing and Painting, Visual Prose, Poetry-Presence, Gaze, University of Tulsa School of Art, Tulsa, OK Jake Berthot, Artist Model, Angel Putti, Poetry Visual Prose, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2010-11 Jake Berthot, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Jake Berthot: Recent Work, Muroff Kotler Visual Arts Gallery, State University of New York Ulster, Stone Ridge, NY 2009 Jake Berthot: New Paintings and Drawings, Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA 2008 Jake Berthot, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY 2007 The Artist / The Artist with the Model, 92nd Street Y, New York, NY 2006 Jake Berthot: Ink Drawings: The Artist and Model, Kleinert/James Art Gallery, Woodstock, NY Jake Berthot, Betty Cuningham Gallery, -

CHRISTOPHER WILMARTH Sculpture and Drawings from the 1970S CHRISTOPHER WILMARTH Sculpture and Drawings from the 1970S

CHRISTOPHER WILMARTH Sculpture and Drawings from the 1970s CHRISTOPHER WILMARTH Sculpture and Drawings from the 1970s CRAIG F. STARR GALLERY Christopher Wilmarth: Light & Place by Joan Pachner For those without an interior life or without an access to it, my work, at best, remains on the level of “beautiful” and can give no more. The rest, which is the most, is not released. Christopher Wilmarth1 Christopher Wilmarth is a modern symbolist whose constructed glass and steel sculptures exemplify American art animated by light and insistent on its role in creating a sense of place. It’s one thing to create the illusion of glowing light in the controlled two-dimensional world of painting but quite another to conjure and harness this kind of landscape effect in sculpture, the literal art that inhabits our space. Wilmarth’s magically balanced abstractions seduce us with their beauty and their innate paradoxical combination of the impregnable and the fragile, balancing sensuous physical beauty with surprising poetic, often achingly expres- sive content. It took time, however, for the artist to identify his materials, and to fgure out how to use them to accomplish his goals; at times the means and message seemed to be in confict, a tension that he ultimately harnessed. I associate the significant moments of my life with the character of light at the time.2 (1974) Light that touches the world, that we remember with particular clarity, was central to Wilmarth’s artistic mission and drove the work’s development towards increasing interiority from the 1960s through to 1987, the year of his suicide at the age of forty-four. -

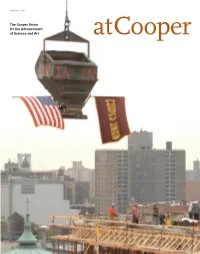

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Atcooper 2 | the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Summer 2008 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art atCooper 2 | The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Message from President George Campbell Jr. Union As the academic year draws to a close, The Cooper Union commu- At Cooper Union Summer 2008 nity can look back over 2007-08 with a profound sense of accom- plishment. At commencement we celebrated four new Fulbright scholars who will pursue their studies in Peru, Tunisia, Japan and Kazakhstan. Since 2001, our graduates have won an astonishing 28 Fulbright scholarships—approximately seven percent of all Fulbright Awards in art, architecture and engineering. Another 149th Commencement 3 National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship was awarded to a Cooper Union graduate this year, bringing the total to 11 since News Briefs 4 2004, making the college also one of the nation’s top producers of New Pledges to Cooper Union NSF Fellowships. Cooper Union’s electrical engineering seniors l e r o S New Trustees swept first, second and third prizes in the student research paper o e Barack Obama Speaks at The Cooper Union L competition sponsored by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Benefactors Join Lifetime Giving Societies Engineers; and our chemical engineering students won first prize In Memoriam: John Jay Iselin in the national Chem-E-Car competition, sponsored by the American Institute of Chemical Engineers and designed to stimulate Features 8 research in alternative fuels. Civil engineering students won one of Dynamic Forces: the concrete canoe competitions and took third place overall in the Jesse Reiser (AR’81) and Nanako Umemoto (AR’83) Steel Bridge competition. -

Raise Your Glass To, Two of the Most Wonderful People I Know

CHRISTOPHER WILMARTH 1943 Born in Sonoma, CA 1965 B.F.A., Cooper Union, New York, NY 1969 Professor of Sculpture and Drawing, Cooper Union, New York, NY 1986 Professor of Sculpture, Columbia University, New York, NY 1987 Died in Brooklyn, NY Solo Exhibitions 2011 Christopher Wilmarth, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, July 7 – August 12 2007-08 Christopher Wilmarth, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, Nov. 29 – January 19 2005 Christopher Wilmarth, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, Oct. 29 – Dec. 3 2003 Christopher Wilmarth Inside Out, Robert Miller Gallery, New York, Oct. 15 – Nov. 15 Christopher Wilmarth: Gift of the Bridge, Related Drawings and Sculpture, Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA, March 29 – May 3 Christopher Wilmarth: Drawing into Sculpture, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, April 5 – June 29 2001 Christopher Wilmarth, The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Sept. 20 – Nov. 3 Christopher Wilmarth: Living Inside, University Gallery, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Amherst, MA 2000 Christopher Wilmarth: Every other Shadow Had a Song to Sing, Robert Miller Gallery, New York, NY, April 6 – May 6 1998 Christopher Wilmarth, 1943-1987, Layers, Clearings, Breath, Nielsen Gallery, Boston, MA, April 8 – May 9 1997 Christopher Wilmarth: Sculpture and Painting from the 1960s and 1980s, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, NY, March 18 – April 19 1996 Christopher Wilmarth: Sculpture, Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York, NY 1995 Christopher Wilmarth, Sidney Janis Gallery, New York 1994 Christopher Wilmarth, DIA Center -

Art School Critique 2.0 Nov 18-19, 2016

Art School Critique 2.0 Nov 18-19, 2016 THE MACY ART GALLERY | 525 WEST 120TH ST | NEW YORK, NY #CTCART | TC.COLUMBIA.EDU/CRITIQUE20 WELCOME TO THE ART SCHOOL CRITIQUE 2.0 SYMPOSIUM Critiques - the presentation and review of student work in front of a teacher or critic and peers - have long been a common and powerful learning tool in the arts. Apart from allowing a deep engagement with the produced work, they also serve as a unique assessment device. Critiques provide a rich learning experience but can also be jarring. With art schools redefining their roles in the larger context of academia, are critiques still necessary? How have the recent changes to the learning landscape — student-centered teaching models, collaborative ways of making and online classrooms — changed the nature and practice of critiques? Art School Critique 2.0 will be a multifaceted exchange of ideas with short presentations, break-out sessions, panels, and workshops; it will explore multiple aspects of critique, including its affordances and shortcomings; the artist as critic; and the role of critique in the curriculum. The symposium will be the third in a series of recent symposia on teaching and learning of studio art in the 21st century. Acknowledging the need for professional development of artist-teachers, we will emphasize conversations rather than lectures, following an understanding of pedagogy as a practical concern rather than an institutional concept. Guiding Questions: What makes critique a powerful instrument for students in the arts, architecture, -

Christopher Wilmarth: Sculpture and Drawings from the 1970S on View at Craig F. Starr Gallery January 30 Through March 14

Christopher Wilmarth: Sculpture and Drawings from the 1970s on view at Craig F. Starr Gallery January 30 through March 14 Light gains character as it touches the world; from what is lighted and who is there to see. I associate the significant moments of my life with the character of light at the time. The universal implications of my original experience have located in and become signified by kinds of light. My sculptures are places to generate this experience compressed into light and shadow and return them to the world as a physical poem. – Christopher Wilmarth. Normal Drawing, 1971. Etched glass and steel cable Second Roebling, 1973. Graphite, paper, and staples 22 x 22 3⁄8 x 1 inches 14 1⁄2 x 11 inches. Beth Rudin DeWoody Craig F. Starr Gallery is pleased to announce an exhibition of work by Christopher Wilmarth (1943- 1987) best known for his glass and steel sculptures which explore the mystical and physical properties of light. Culled from collections across the country, seven sculptures and eight drawings will be on view January 30 through March 14. The show will be accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with a new essay by Joan Pachner. Born in Sonoma, CA in 1943, Wilmarth was raised in the Bay Area. He moved to New York City in the early 1960s, where he attended The Cooper Union School, graduating in 1965. In the city, he found an urban landscape awash with light, the gleam of the surrounding rivers and the metallic facades of skyscrapers compelling his attentions. Wilmarth soon arrived at glass as his preferred medium, a material capable of capturing, reflecting, and refracting light to illusory and emotional effect. -

School of Art 2005–2006

ale university May 10, 2005 2006 – Number 1 bulletin of y Series 101 School of Art 2005 bulletin of yale university May 10, 2005 School of Art Periodicals postage paid New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8227 ct bulletin of yale university bulletin of yale New Haven Bulletin of Yale University The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and affirmatively seeks to Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, attract to its faculty, staff, and student body qualified persons of diverse backgrounds. In PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against any individual on PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, status as a special disabled Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Issued seventeen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times University policy is committed to affirmative action under law in employment of women, a year in June; three times a year in July and September; six times a year in August minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans. Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valerie O. -

1 David Cohen's Writings on Art, Lectures And

DAVID COHEN’S WRITINGS ON ART, LECTURES AND EXHIBITIONS last updated June 2012 Books and Essays Books Henry Moore in the Bagatelle Gardens, Paris, photographs by Michel Muller with an essay by David Cohen (London: Lund Humphries, and New York: Overlook Press, 1993) an overview of Moore's work stressing the importance of landscape to his aesthetic; the book records an important outdoor exhibition staged the previous year in Paris Jock McFadyen: A Book about a Painter (London: Lund Humphries, 2001) By David Cohen, with contributions from Lewis Biggs, Humphrey Ocean, Bob and Roberta Smith, Hugo Williams, Tom Lubbock, Ian Dury, Mary Rose Beaumont, Duncan Macmillan, Jeffery Camp, and Will Self David Cohen Alex Katz Collages: A catalogue raisonné (Waterville, Maine: Colby College Mueum of Art, 2005) Published in conjunction with an exhibition at Colby College Museum of Art June 26 – September 18, 2005 Serban Savu (co-author Rozalinda Borcila) (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2011) Contributions to books and encyclopaedias “Francis Bacon”, “Jacob Epstein”, “Barbara Hepworth”, “Aristide Maillol”, “Ben Nicholson” and “Graham Sutherland” in International Dictionary of Artists and works by the above in International Dictionary of Art twin volumes edited by James Vinson (London: St. James's Press, 1990). "Herbert Read and Psychoanalysis" in Art Criticism since 1890: Authors, Texts, Contexts, edited by Malcolm Gee (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993) considers Read’s early interest in variety of psychoanalytic schools and their bearings on problems of literary criticism, proceeding to his growing interest in C.G.Jung and particular reference to Henry Moore The Annual Register: A Record of World Events 1994 edited by Alan J.