Explorations in Ethnic Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IJSAP Volume 01, Number 04

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 7-1980 IJSAP Volume 01, Number 04 Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/v1_ijsap Recommended Citation "IJSAP Volume 01, Number 04" (1980). IJSAP VOL 1. 4. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/v1_ijsap/4 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International for :the Study of Journal An1n1al Problems VOLUME 1 NUMBER 4 JULY/AUGUST 1980 ., ·-·.··---:-7---;-~---------:--;--·- ·.- . -~~·--· -~-- .-.-,. ") International I for the Study of I TABLE OF CONTENTS-VOL. 1(4) 1980 J ournal Animal Problems EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD EDITORIALS EDITORIAL OFFICERS Alternatives and Animal Rights: A Reply to Maurice Visscher D.K. Belyaev, Institute of Cytology Editors-in-Chief A.N. Rowan 210-211 and Genetics, USSR Advocacy, Objectivity and the Draize Test- P. Singer 211-213 Michael W. Fox, Director, !SAP J.M. Cass, Veterans Administration, USA Andrew N. Rowan, Associate Director, ISAP S. Clark, University of Glasgow, UK j.C. Daniel, Bombay Natural History Society, FOCUS 214-217 Editor India C.L. de Cuenca, University of Madrid, Spain Live Animals in Car Crash Studies Nancy A. Heneson I. Ekesbo, Swedish Agricultural University, Sweden NEWS AND REVIEW 218-223 Managing Editor L.C. Faulkner, University of Missouri, USA Abstract: Legal Rights of Animals in the U.S.A. M.F.W. Festing, Medical Research Council Nancie L. Brownley Laboratory Animals Centre, UK Companion Animals A. F. Fraser, University of Saskatchewan, Associate Editors Pharmacology of Succinylcholine Canada Roger Ewbank, Director T.H. -

The President's Commission on the Celebration of Women in American

The President’s Commission on Susan B. Elizabeth the Celebration of Anthony Cady Women in Stanton American History March 1, 1999 Sojourner Lucretia Ida B. Truth Mott Wells “Because we must tell and retell, learn and relearn, these women’s stories, and we must make it our personal mission, in our everyday lives, to pass these stories on to our daughters and sons. Because we cannot—we must not—ever forget that the rights and opportunities we enjoy as women today were not just bestowed upon us by some benevolent ruler. They were fought for, agonized over, marched for, jailed for and even died for by brave and persistent women and men who came before us.... That is one of the great joys and beauties of the American experiment. We are always striving to build and move toward a more perfect union, that we on every occasion keep faith with our founding ideas and translate them into reality.” Hillary Rodham Clinton On the occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the First Women’s Rights Convention Seneca Falls, NY July 16, 1998 Celebrating Women’s History Recommendations to President William Jefferson Clinton from the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. Ellen Ochoa, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, Irene Wurtzel March 1, 1999 Table of Contents Executive Order 13090 ................................................................................1 -

Colorado's 3Rd Congressional District in 1992, and Presently Serves on the Natural Resources and Small Business Committees

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu (/) n :c m 0 c r m Page 1 of 36 Ouo DOLC: ID· 202 408 511 ( SEP 02'94 1--g:s4 No.015 P.06 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu IUESDAY. SEPTEMBER 6,_12li · · Page five 4:15 pm DEPART Rally for airport Driver: Ken Frahm Drive time: 10 minutes 4:25 pm ARRIVE airport and proceed to departing aircraft FBO: Roesch Aviation 913/462-264 7 4:30 pm DEPART Colby, KS for Grand Junction, CO!Parker Field FBO: West Star Aviation Aircraft: Challenger Tail number: N25SB Flight time: 1 hour 15 minutes Pilots: Dave Fontanella Frank Desetto' Seats: 9 Meal: Snack Manifest: Senator Dole Mike Glassner John Atwood Chris Swonger Contact: Blanche Durney 203/622-4435 914/997-2145 fax Time change: - 1 hour • 4:45 pm ARRIVE Grand Junction, CO FBO: West Star Aviation 303/243-7500 Met by: Rick Schroeder Congressman Scott Mcinnis 4:50 pm- Press Avail 5:05 pm Location: Lobby of West Star Aviation 5:05 pm DEPART airport for Fundraising Reception for Scott Mcl1U1is Driver: Kelly Caldwell, Mclnnis staff Drive time: 15 minutes Location: Home of Andrea and Rick Schroeder Mesa Mood Ranch • Page 2 of 36 CO O DUL t: 1 0 . 202 408 511? This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, UniversitySEP 02 of Kansas''3Zl 18 :jj No.015 P.07 http://dolearchives.ku.edu TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, llli Page six 5:20 pm ARRIVE Home of Andrea and Rick Schroeder 303/245-9297 Met by: Lori Mclnnis Andrea Schroeder 5:20 pm- ArfEND/SPEAK Fundraising Reception for Scott Mcinnis 6:20 pm Location: Back yard deck Attendance: 45 @$100 per person Event runs: 12:00 - 1 :00 pm Press: Maybe someone from People Maga7.ine Facility: No podium ~r mic Format.: Mix and mingle . -

Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 1 Nov-2006 Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P. Watson Recommended Citation Watson, Robert P. (2006). Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 1-20. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss1/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2006 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 By Robert P. Watson1 Abstract Women have made great progress in electoral politics both in the United States and around the world, and at all levels of public office. However, although a number of women have led their countries in the modern era and a growing number of women are winning gubernatorial, senatorial, and congressional races, the United States has yet to elect a female president, nor has anyone come close. This paper considers the prospects for electing a woman president in 2008 and the challenges facing Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice–potential frontrunners from both major parties–given the historical experiences of women who pursued the nation’s highest office. -

The Denver Catholic Register

The Denver Catholic Register VOL. LI WEDNESDAY, MAY 19,1976 NO. 41 15 CENTS PER COPY 28 PAGES For Human Life Amendment G rassroots C a m p a i g n O r g a n i z e d By James Fiedler A grassroots campaign for a human life amendment to the U.S. Con stitution is being organized in Colorado by pro-life leaders in the Archdiocese. The campaign will involve establishing Congressional District Ac tion Committees in each congressional district. Organizational plans and techniques for the ambitious effort were outlined March 12 at a meeting for area pro-life leaders by two represen tatives of the Washington, D.C.-based National Committee for a Human Life Amendment (NCHLA), supported by U.S. bishops. The NCHLA officials — William Cox, executive director, and Mary Helen Madden, associate director — explained that their organization lias started efforts to organize action committees for a human life amendment in all of the more than 400 Congressional districts in the country. Cox told the Denver meeting that although the need for an anti abortion amendment to the Constitution is clear, support for it in Congress has been decreasing. Congressmen, Cox contended, are finding it “easy and convenient” to avoid support for such an amendment. Even Congressional districts with a high percentage of Catholics continue to send Congressmen to Washington who do not support a human life amendment. The establishment of Congressional District Action Committees nationwide is necessary, Cox charged, because Congress is not organized to deal with principles and ideals. Congress, however, does react to and is influenced by well-organized, effective in terest and lobbying groups such as labor unions. -

2021 Series Booklet

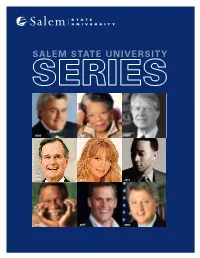

SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY SERIES 2009 2007 1984 1994 2007 2003 2017 2001 2015 2002 SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY SERIES In 1982, Salem State invited President Gerald Ford, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and renowned journalist Douglas Kiker to speak at the college during that academic year. Each of their presentations was open to the public, and the response was tremendous. Thus was born the Salem State Series. In the 39 years since, ever-larger audiences have enjoyed the opportunity to hear presidents, press secretaries and prime ministers; activists, actors and authors; legendary figures from the world of sports, politics and science; and authors, columnists and journalists. The Salem State Series stands now as one of the premier continuously running college lecture series in the country, attracting thousands of patrons annually. We plan once again to present notable speakers on subjects designed to inform, engage and encourage discussion within the community. We hope to count you among our supporters. The Salem State Series is produced under the auspices of the Salem State Foundation. As a self-supporting community enrichment program, the Series assists the university in fulfilling its public education mission. We are grateful to the thousands of individuals and businesses that have enabled the Series to grow and prosper through their ongoing financial support. 2020 2019 2018 Paul Farmer Rebecca Eaton Sam Kennedy Paul Farmer 2017 2016 2015 John Legend Richard DesLauriers Ed Davis Tom Brady 2013 2012 Tony Kushner Cory Booker Bobby Valentine Peter Gammons 2011 2010 Newt Gingrich John Irving Deepak Chopra Ted Kennedy Jr. 2009 2008 Jay Leno Bob and Lee Woodruff Bill Belichick George F. -

SBA Chief of Staff to Speak at New ABA Session at BEA Session at BEA

May 07, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS: SBA Chief of Staff to Speak at New ABA • SBA Chief of Staff to Speak at New ABA Session at BEA Session at BEA ................................................ 1 May 07, 2009 -- Ana M. Ma, chief of staff at the U.S. Small • ABA Annual Meeting to Include Vote to Amend Business Administration, will be one of the featured speakers at a Bylaws .............................................................. 2 new ABA session at BookExpo America, "How SBA and the Federal Stimulus Package Can Help Your Business," to be held • IndieBound on the Rise! ................................... 3 Saturday, May 30, from 10:30 a.m. - noon, at the Javits Convention • Wine Guru Gary Vaynerchuk to Lead Social Center. Media Session at BEA ...................................... 3 "Ms. Ma is looking forward to talking with the members of the • ABA Announces Details of New CEO Contract American Booksellers Association," said SBA spokesman Jonathan .......................................................................... 3 Swain. "Ms. Ma will share what the SBA is doing as part of the • Trade Associations Call on Minnesota Recovery Act to help small businesses get access to much-needed Governor to Support E-Fairness Bill ................. 3 capital in these tough economic times, and how SBA is working to be a real partner with small businesses across the country in • North Carolina Latest State to Introduce creating jobs and driving our nation's economic recovery." Internet Sales Tax Provision ............................ 5 "We're delighted to have someone as knowledgeable about small • ABACUS Survey Works to Increase business issues as Ana Ma speak at this very important educational Participation: How Bookstores Benefit ............. 5 session," said ABA COO Oren Teicher, who will serve as • BTW Talks With New AAP Head Tom Allen ... -

Olympia J. Snowe

Olympia J. Snowe U.S. SENATOR FROM MAINE TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:36 Apr 24, 2014 Jkt 081112 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81112.TXT KAYNE congress.#15 Olympia J. Snowe VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:36 Apr 24, 2014 Jkt 081112 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81112.TXT KAYNE 81112.002 S. DOC. 113–14 Tributes Delivered in Congress Olympia J. Snowe United States Congresswoman 1979–1995 United States Senator 1995–2013 ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2014 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:36 Apr 24, 2014 Jkt 081112 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81112.TXT KAYNE Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:36 Apr 24, 2014 Jkt 081112 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 H:\DOCS\BYEBYE\BYEBYE12\81112.TXT KAYNE CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. v Farewell Address ...................................................................................... ix Proceedings in the Senate: Tributes by Senators: Boxer, Barbara, of California .................................................... 25 Cardin, Benjamin L., of Maryland ............................................ 20 Collins, Susan M., of Maine ...................................................... 3 Conrad, Kent, of North Dakota ................................................. 12 Enzi, Michael B., of Wyoming .................................................. -

Extensions of Remarks

February 25, 1992 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 3397 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS THE PEACE PROCESS IN EL Jesuit University of Central America and losing the crop and thus El Salvador's sec SALVADOR brutally killed six priests, a housekeeper and ond-largest source of foreign capital after her daughter. · the United States' contribution to the war Salvadorans long for assurances that these effort. If the majority of people were gain HON. MICHAEL R. McNULlY massacres will end. They know it is not fully employed in a stable economy, there OF NEW YORK enough to sign a document saying "the would be no workers for the harvest. The IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Armed Forces and the F.M.L.N. will respect Salvadoran export economy, therefore, de human rights." Such assurances have been pends as much on seasonal unemployment Tuesday, February 25, 1992 offered in the past. Called, variously, "mes and underemployment (from February until Mr. McNULTY. Mr. Speaker, one of my con sages," " symbols, " "indications" and "signs October) as on available labor from Novem stituents, Sister Jane Brooks, CSJ, was kind of peace," they have been ineffectual. Mas ber until January. The wages from the harvest are low and enough to send me a very important article sacres are not the cause of El Salvador's problems, they are a consequence of larger are used to purchase clothing or shoes for entitled, "The Peace Process in El Salvador injustices. The dialogue for peace must ad the children and possibly a few Christmas (A Hermeneutic of Suspicion)," by the Rev dress the underlying causes of the conflict as presents. -

Document Resume

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 367 SO 024 584 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers, 1994. REPORT NO ISSN-1058-2347 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 444p.; For volumes 1-2, see ED 363 546. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, Inc., Penobscot Building, Detroit, Michigan 48226. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Biography Today; v3 n1-3 1994 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC18 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Artists; Authors; *Biographies; Elementary Secondary Education; *Popular Culture; Profiles; Recreational Reading; *Role Models; *Student Interests; Supplementary Reading Materials ABSTRACT This document is the third volume of a series designed and written for the young reader aged 9 and above. It contains three issues and covers individuals that young people want to know about most: entertainers, athletes, writers, illustrators, cartoonists, and political leaders. The publication was created to appeal to young readers in a format they can enjoy reading and readily understand. Each issue contains approximately 20 sketches arranged alphabetically. Each entry combines at least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead the reader to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, first jobs, marriage and family, career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies, and honors and awards. Each of the entries ends with a list of easily accessible sources to lead the student to further reading on the individual and a current address. Obituary entries also are included, written to prcvide a perspective on an individual's entire career. Beginning with this volume, the magazine includes brief entries of approximately two pages each. -

Biography Today: Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 454 140 SO 032 850 AUTHOR Abbey, Cherie D., Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers. Author Series, Volume 9. ISBN ISBN-0-7808-0462-7 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 216p.; For related volumes in the Author Series, see ED 390 725, ED 434 064, ED 446 010, and ED 448 069. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, Inc., 615 Griswold Street, Detroit, MI 48226; Tel: 800-234-1340 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.omnigraphics.com/. PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Authors; Biographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Language Arts; Popular Culture; Profiles; Student Interests; Supplementary Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS *Biodata ABSTRACT This book presents biographical profiles of 10 authors of interest to readers ages 9 and above and was created to appeal to young readers in a format they can enjoy and readily understand. Biographies were prepared after extensive research, and each volume contains a cumulative index, a general index, a place of birth index, and a birthday index. Each profile provides at least one picture of the individual and information on birth, youth, early memories, education, first jobs, marriage and family, career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies, and honors and awards. All entries end with a list of easily accessible sources designed to lead the student to further reading on the individual. Obituary entries are also included, written to provide a perspective on the individual's entire career. Obituaries are clearly marked in both the table of contents and at the beginning of the entry. -

2018 State Convention Booklet

“Exploring Community Involvement and Collaboration” 2018 AAUW Colorado State Convention Littleton, Colorado - April 27-28, 2018 AAUW Littleton-South Metro Branch Welcomes You to the 91st State Convention http://aauw-co.aauw.net/ AAUW: Advancing equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, philanthropy, and research. In principle and practice, AAUW values and seeks a diverse membership. There shall be no barriers to full participation in this organization on the basis of gender, race, creed, age, sexual orientation, national origin, disability, or class. Table of Contents Cover Table of Contents & Mission Statement 1 Convention Program Schedule 3 Welcome by National President 4 Welcome Colorado President 5 History of Host Branch 6 Speakers Bios Julia Brown & Karina Elrod 7 Dr. Belinda Aaron, Regan Byrd, & Dr. Shirley Miles 8 Dr. Marilyn Thomas Leist & Katherine Olivier 9 Proposed 2018 Convention Rules 10 Annual Business Meeting Agenda 11 Proposed Bylaw Amendments 12 - 18 Nominating Committee Report 19 AAUW Colorado Strategic Plan 20 - 21 State Officer Reports President 22 President-Elect 23 Program VPs 24 Funds 25 - 26 Membership 27 Public Policy 28 Communications 29 Interbranch Council 30 Archivist Report 31 Bylaws Committee Report 32 Branch Reports Aurora 33 Boulder 34 COeNetwork 35 Colorado Springs 36 Douglas County 37 Durango 38 Fort Collins 39 Grand Junction 40 Gunnison 41 Lakewood 42 Littleton South Metro 43 Longmont 44 Loveland 45 State Officers Directory 2016-17 46 - 47 Colorado AAUW Conventions 48 Colorado AAUW Presidents 49 Brief History Colorado State 50 - 51 AAUW’s Mission: Advancing equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, philanthropy, and research 1 AAUW Colorado 2018 State Convention Program Schedule April 27-28, 2018 “Exploring Community Involvement and Collaboration” Hosted by the Littleton-South Metro Branch Hilton Garden Inn, 1050 Plaza Drive, Highlands Ranch, CO 80126 Friday 1:30 p.m.