Deborah D. Pryce Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

IJSAP Volume 01, Number 04

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 7-1980 IJSAP Volume 01, Number 04 Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/v1_ijsap Recommended Citation "IJSAP Volume 01, Number 04" (1980). IJSAP VOL 1. 4. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/v1_ijsap/4 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International for :the Study of Journal An1n1al Problems VOLUME 1 NUMBER 4 JULY/AUGUST 1980 ., ·-·.··---:-7---;-~---------:--;--·- ·.- . -~~·--· -~-- .-.-,. ") International I for the Study of I TABLE OF CONTENTS-VOL. 1(4) 1980 J ournal Animal Problems EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD EDITORIALS EDITORIAL OFFICERS Alternatives and Animal Rights: A Reply to Maurice Visscher D.K. Belyaev, Institute of Cytology Editors-in-Chief A.N. Rowan 210-211 and Genetics, USSR Advocacy, Objectivity and the Draize Test- P. Singer 211-213 Michael W. Fox, Director, !SAP J.M. Cass, Veterans Administration, USA Andrew N. Rowan, Associate Director, ISAP S. Clark, University of Glasgow, UK j.C. Daniel, Bombay Natural History Society, FOCUS 214-217 Editor India C.L. de Cuenca, University of Madrid, Spain Live Animals in Car Crash Studies Nancy A. Heneson I. Ekesbo, Swedish Agricultural University, Sweden NEWS AND REVIEW 218-223 Managing Editor L.C. Faulkner, University of Missouri, USA Abstract: Legal Rights of Animals in the U.S.A. M.F.W. Festing, Medical Research Council Nancie L. Brownley Laboratory Animals Centre, UK Companion Animals A. F. Fraser, University of Saskatchewan, Associate Editors Pharmacology of Succinylcholine Canada Roger Ewbank, Director T.H. -

The President's Commission on the Celebration of Women in American

The President’s Commission on Susan B. Elizabeth the Celebration of Anthony Cady Women in Stanton American History March 1, 1999 Sojourner Lucretia Ida B. Truth Mott Wells “Because we must tell and retell, learn and relearn, these women’s stories, and we must make it our personal mission, in our everyday lives, to pass these stories on to our daughters and sons. Because we cannot—we must not—ever forget that the rights and opportunities we enjoy as women today were not just bestowed upon us by some benevolent ruler. They were fought for, agonized over, marched for, jailed for and even died for by brave and persistent women and men who came before us.... That is one of the great joys and beauties of the American experiment. We are always striving to build and move toward a more perfect union, that we on every occasion keep faith with our founding ideas and translate them into reality.” Hillary Rodham Clinton On the occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the First Women’s Rights Convention Seneca Falls, NY July 16, 1998 Celebrating Women’s History Recommendations to President William Jefferson Clinton from the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. Ellen Ochoa, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, Irene Wurtzel March 1, 1999 Table of Contents Executive Order 13090 ................................................................................1 -

Colorado's 3Rd Congressional District in 1992, and Presently Serves on the Natural Resources and Small Business Committees

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu (/) n :c m 0 c r m Page 1 of 36 Ouo DOLC: ID· 202 408 511 ( SEP 02'94 1--g:s4 No.015 P.06 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu IUESDAY. SEPTEMBER 6,_12li · · Page five 4:15 pm DEPART Rally for airport Driver: Ken Frahm Drive time: 10 minutes 4:25 pm ARRIVE airport and proceed to departing aircraft FBO: Roesch Aviation 913/462-264 7 4:30 pm DEPART Colby, KS for Grand Junction, CO!Parker Field FBO: West Star Aviation Aircraft: Challenger Tail number: N25SB Flight time: 1 hour 15 minutes Pilots: Dave Fontanella Frank Desetto' Seats: 9 Meal: Snack Manifest: Senator Dole Mike Glassner John Atwood Chris Swonger Contact: Blanche Durney 203/622-4435 914/997-2145 fax Time change: - 1 hour • 4:45 pm ARRIVE Grand Junction, CO FBO: West Star Aviation 303/243-7500 Met by: Rick Schroeder Congressman Scott Mcinnis 4:50 pm- Press Avail 5:05 pm Location: Lobby of West Star Aviation 5:05 pm DEPART airport for Fundraising Reception for Scott Mcl1U1is Driver: Kelly Caldwell, Mclnnis staff Drive time: 15 minutes Location: Home of Andrea and Rick Schroeder Mesa Mood Ranch • Page 2 of 36 CO O DUL t: 1 0 . 202 408 511? This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, UniversitySEP 02 of Kansas''3Zl 18 :jj No.015 P.07 http://dolearchives.ku.edu TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, llli Page six 5:20 pm ARRIVE Home of Andrea and Rick Schroeder 303/245-9297 Met by: Lori Mclnnis Andrea Schroeder 5:20 pm- ArfEND/SPEAK Fundraising Reception for Scott Mcinnis 6:20 pm Location: Back yard deck Attendance: 45 @$100 per person Event runs: 12:00 - 1 :00 pm Press: Maybe someone from People Maga7.ine Facility: No podium ~r mic Format.: Mix and mingle . -

That Changed Everything

2 0 2 0 - A Y E A R that changed everything DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION DECEMBER 18, 2020 For Florida students in grades 6 - 8 PRESENTED BY THE FLORIDA COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN To commemorate and honor women's history and PURPOSE members of the Florida Women's Hall of Fame Sponsored by the Florida Commission on the Status of Women, the Florida Women’s History essay contest is open to both boys and girls and serves to celebrate women's history and to increase awareness of the contributions made by Florida women, past and present. Celebrating women's history presents the opportunity to honor and recount stories of our ancestors' talents, sacrifices, and commitments and inspires today's generations. Learning about our past allows us to build our future. THEME 2021 “Do your part to inform and stimulate the public to join your action.” ― Marjory Stoneman Douglas This year has been like no other. Historic events such as COVID-19, natural disasters, political discourse, and pressing social issues such as racial and gender inequality, will make 2020 memorable to all who experienced it. Write a letter to any member of the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame, telling them about life in 2020 and how they have inspired you to work to make things better. Since 1982, the Hall of Fame has honored Florida women who, through their lives and work, have made lasting contributions to the improvement of life for residents across the state. Some of the most notable inductees include singer Gloria Estefan, Bethune-Cookman University founder Mary McLeod Bethune, world renowned tennis athletes Chris Evert and Althea Gibson, environmental activist and writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Pilot Betty Skelton Frankman, journalist Helen Aguirre Ferre´, and Congresswomen Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Carrie Meek, Tillie Fowler and Ruth Bryan Owen. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

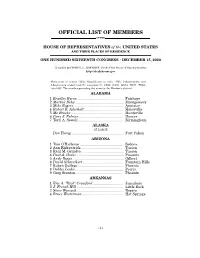

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 1 Nov-2006 Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P. Watson Recommended Citation Watson, Robert P. (2006). Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 1-20. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss1/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2006 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 By Robert P. Watson1 Abstract Women have made great progress in electoral politics both in the United States and around the world, and at all levels of public office. However, although a number of women have led their countries in the modern era and a growing number of women are winning gubernatorial, senatorial, and congressional races, the United States has yet to elect a female president, nor has anyone come close. This paper considers the prospects for electing a woman president in 2008 and the challenges facing Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice–potential frontrunners from both major parties–given the historical experiences of women who pursued the nation’s highest office. -

Canada, the United States, and Biological Terrorism

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 A plague on both our houses: Canada, the United States, and biological terrorism Winzoski, Karen Jane Winzoski, K. J. (2001). A plague on both our houses: Canada, the United States, and biological terrorism (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/13326 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40836 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca I UNEVERSrrY OF CALGARY A Plague on Both Our Houses: Ca- the United States, and BiologicaI Terrorism by Karen Jane Winzoski A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARWFULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 200 t Q Karen Jane Wioski 200 1 National Library Bibiiothbque nationale du Canada A uisitionsand Acquisitions et ~aog~hiiSewices sewices biblographiques 395WolAng(ocrStreel 385. we WePingttm OuawaON KtAW -ON KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde me licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National hiof Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, prk,distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Congressional Pictorial Directory.Indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman

S. Prt. 112-1 One Hundred Twelfth Congress Congressional Pictorial Directory 2011 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 2011 congressional pictorial directory.indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800; Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-087912-8 online version: www.fdsys.gov congressional pictorial directory.indb II 5/16/11 10:19 AM Contents Photographs of: Page President Barack H. Obama ................... V Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. .............VII Speaker of the House John A. Boehner ......... IX President pro tempore of the Senate Daniel K. Inouye .......................... XI Photographs of: Senate and House Leadership ............XII-XIII Senate Officers and Officials ............. XIV-XVI House Officers and Officials ............XVII-XVIII Capitol Officials ........................... XIX Members (by State/District no.) ............ 1-152 Delegates and Resident Commissioner .... 153-154 State Delegations ........................ 155-177 Party Division ............................... 178 Alphabetical lists of: Senators ............................. 181-184 Representatives ....................... 185-197 Delegates and Resident Commissioner ........ 198 Closing date for compilation of the Pictorial Directory was March 4, 2011. * House terms not consecutive. † Also served previous Senate terms. †† Four-year term, elected 2008. congressional pictorial directory.indb III 5/16/11 10:19 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb IV 5/16/11 10:19 AM Barack H. Obama President of the United States congressional pictorial directory.indb V 5/16/11 10:20 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb VI 5/16/11 10:20 AM Joseph R. -

The Denver Catholic Register

The Denver Catholic Register VOL. LI WEDNESDAY, MAY 19,1976 NO. 41 15 CENTS PER COPY 28 PAGES For Human Life Amendment G rassroots C a m p a i g n O r g a n i z e d By James Fiedler A grassroots campaign for a human life amendment to the U.S. Con stitution is being organized in Colorado by pro-life leaders in the Archdiocese. The campaign will involve establishing Congressional District Ac tion Committees in each congressional district. Organizational plans and techniques for the ambitious effort were outlined March 12 at a meeting for area pro-life leaders by two represen tatives of the Washington, D.C.-based National Committee for a Human Life Amendment (NCHLA), supported by U.S. bishops. The NCHLA officials — William Cox, executive director, and Mary Helen Madden, associate director — explained that their organization lias started efforts to organize action committees for a human life amendment in all of the more than 400 Congressional districts in the country. Cox told the Denver meeting that although the need for an anti abortion amendment to the Constitution is clear, support for it in Congress has been decreasing. Congressmen, Cox contended, are finding it “easy and convenient” to avoid support for such an amendment. Even Congressional districts with a high percentage of Catholics continue to send Congressmen to Washington who do not support a human life amendment. The establishment of Congressional District Action Committees nationwide is necessary, Cox charged, because Congress is not organized to deal with principles and ideals. Congress, however, does react to and is influenced by well-organized, effective in terest and lobbying groups such as labor unions. -

2021 Series Booklet

SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY SERIES 2009 2007 1984 1994 2007 2003 2017 2001 2015 2002 SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY SERIES In 1982, Salem State invited President Gerald Ford, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and renowned journalist Douglas Kiker to speak at the college during that academic year. Each of their presentations was open to the public, and the response was tremendous. Thus was born the Salem State Series. In the 39 years since, ever-larger audiences have enjoyed the opportunity to hear presidents, press secretaries and prime ministers; activists, actors and authors; legendary figures from the world of sports, politics and science; and authors, columnists and journalists. The Salem State Series stands now as one of the premier continuously running college lecture series in the country, attracting thousands of patrons annually. We plan once again to present notable speakers on subjects designed to inform, engage and encourage discussion within the community. We hope to count you among our supporters. The Salem State Series is produced under the auspices of the Salem State Foundation. As a self-supporting community enrichment program, the Series assists the university in fulfilling its public education mission. We are grateful to the thousands of individuals and businesses that have enabled the Series to grow and prosper through their ongoing financial support. 2020 2019 2018 Paul Farmer Rebecca Eaton Sam Kennedy Paul Farmer 2017 2016 2015 John Legend Richard DesLauriers Ed Davis Tom Brady 2013 2012 Tony Kushner Cory Booker Bobby Valentine Peter Gammons 2011 2010 Newt Gingrich John Irving Deepak Chopra Ted Kennedy Jr. 2009 2008 Jay Leno Bob and Lee Woodruff Bill Belichick George F.